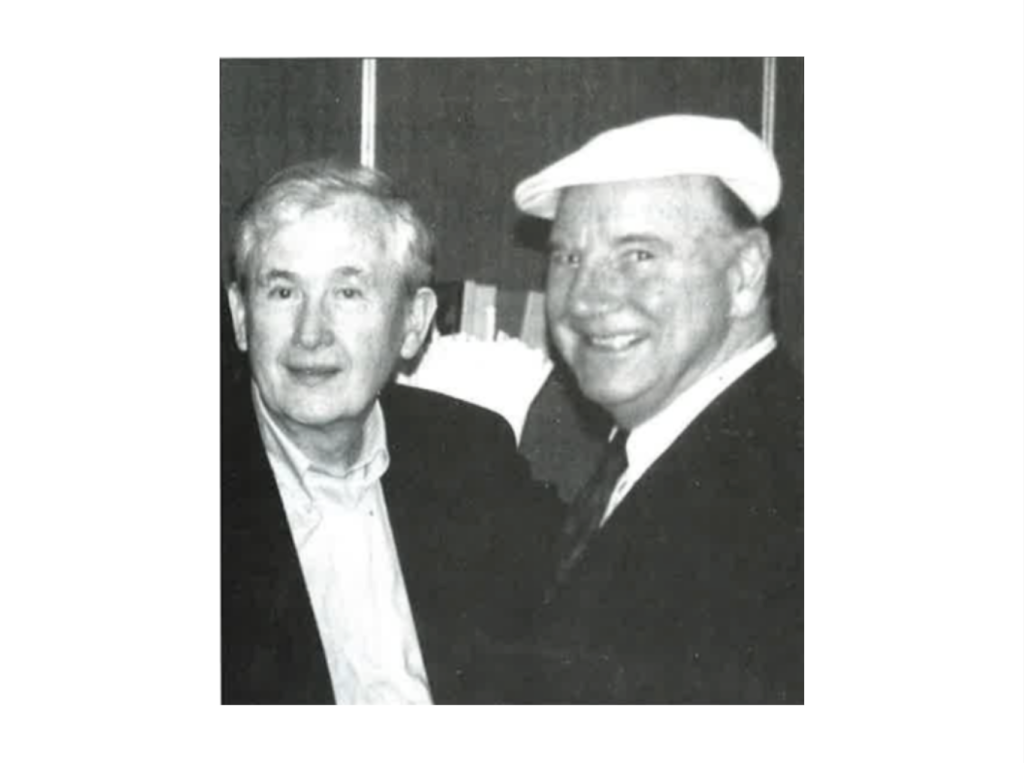

Frank McCourt looks back on a friendship of forty years with folk singer Paddy Clancy, and the times they had hanging out in such Greenwich Village bars as the White Horse Tavern and the Lion’s Head.

We’re heading towards the end of 1999 and there are some, including myself, who may not see another year with a 9 in it.

And isn’t that the gloomiest opening sentence you ever read in your life?

Still, it had to be written because they’re going, my generation, the silent generation, slipping gently, one by one, into that good night, going with grace — unlike the bleating baby boomers behind us who seem to think they’re exempt from mutability.

This has to be written because now The Call comes more often: “How are you, Frank? Do you know who died?” When couched like that I know it’s one of my brothers, Alphie, Michael, Malachy, and we sense the old joke shimmering in the background.

“Hello there, Pat. Do you know who died?”

“No. Who?”

“Eamonn Lynch from Carey’s Road.”

“Aw, God rest him, and what did he die of?”

“Oh, nothin’ serious.”

“Well, thank God for that.”

The Call came last year when Paddy Clancy died after months of struggling with a brain tumor. At first there was some satisfaction in the sweetness of Paddy’s going: in his own bed, surrounded by his family, grandchildren crawling over him, his mind wandering when he asked if his own parents would come to his funeral. Of course it was a sad call, though it sent me back over the forty years of our friendship, back to our early days in Greenwich Village, back to the White Horse Tavern, back to the San Remo, the Limelight on Sheridan Square and, above all, back to the Lion’s Head on Christopher Street.

In the nineteen fifties you could stand at the bar of the White Horse Tavern and listen to the talk. You might hear Daniel Patrick Moynihan on history, Delmore Schwartz on poetry, Michael Harrington on the poor, Kevin Sullivan on Irish literature. A “regular,” cadging a drink, might be telling a tourist how Dylan Thomas drank himself to death at this very bar and often the tourist would say, “Who’s Dylan Thomas?”

With all this talking and drinking there was background music — the Clancy Brothers and Tommy Makem singing away in a small room up a couple of steps. Makem came from a musical family in the North but the Clancys, I think, were discovering the power of traditional Irish song. Paddy and Tom Clancy had knocked around the world till they came to rest in Greenwich Village where they acted and produced plays at the Cherry Lane Theater. Then, when brother Liam arrived from Ireland, they began to sing for their own label, Tradition Records. They sang at small venues all over the country till Ed Sullivan invited them on his show and that was the big time.

They were the first. Before them there were dance bands and show bands and céilidhe bands on both sides of the Atlantic. There were individual performers like Delia Murphy, Ruthie Morrissey, Mickey Carton, but not since John McCormack had Irish singers captured international attention like the Clancy Brothers and Tommy Makem. They opened the gates to the likes of the Dubliners and the Wolfe Tones and every Irish group thereafter. Their straightforward, good-humored delivery restored life to many an Irish song that had suffocated for years under layers of syrup. They simply cut the sentiment and allowed each song its own dignity. They sang their songs. They didn’t preach. And they were loved everywhere.

When Paddy died he was referred to as the “strong man” of the group. He often laughed and told me he didn’t think much of himself as a singer, that Tommy Makem was the real musician in the group, that Liam was the Voice. (Bob Dylan once said Liam had a better voice than anyone in the business.) Despite all the traveling and singing, all the adulation and glamour, Paddy knew what he wanted — that 150-acre farm in Carrickon-Suir in Tipperary, and when he married Mary Flannery from Mayo they stocked the place with prize French cows. When he wasn’t all over the world singing, Paddy, gentleman farmer always dressed in suit, shirt, tie, would wander the farm puffing on his pipe, discussing the ways of cows with his hired man, Gus, who knew everything about every farm animal in Tipperary, their seed, breed and generation. Gus could look at a cow from a hundred yards away and tell you if she was ready for the bull or beyond the bull. Gus could stick his nose in the air and tell you when the rain might come or if the sun had a notion of appearing today, and it was this man, Gus, I think, that Paddy admired most in the world because Gus was a genius out of the earth itself, the element Paddy loved most.

Whatever Paddy knew he discovered for himself and, because he read constantly, he wasn’t shy about his lack of formal education. Someone told him in the Lion’s Head one night he was an erudite man and he laughed. “I’m as erudite as shit,” he said, though his head was crammed with poetry and history and whatever he learned from Gus. Poets and writers would pass through the Lion’s Head and Paddy was always ready to talk — or to listen. He would puff on his pipe — and listen. He and Kevin Sullivan were powerful listeners and when I began to write I thought of them as the ideal audience, the perfect readers.

I am writing about Paddy Clancy because I loved him and because his death last year stirred up sweet memories of other ghosts from the Lion’s Head Bar: Joe Flaherty, Joel Oppenheimer, Kevin Sullivan, Archie Mulligan, Tommy Butler, Wes Joice, Mike Reardon, Nick Brown.

After thirty years the Lion’s Head closed in 1996. It had become my home away from home, the place where we mumbled into our pints over troubled romances, crumbling marriages, wayward children, and careers gone astray. There was drink, of course, and there were long nights and hideous hangovers, but there were friendships and I am blessed for having known the likes of Paul Schiffman, Jack Deacy, Sheila McKenna, Dennis Duggan, Bill Flanagan, Barry Murphy, Pete Hamill and Jack Meehan.

Oh, the times I’ve had at the Head, and it was Paddy Clancy who invited me there on opening night.

Editor’s Note: This article was originally published in the November 1999 issue of Irish America. ⬥

Leave a Reply