Nellie Bly

Newshound

“Energy rightly applied can accomplish anything.”

Nellie Bly’s biographer, Brooke Kroeger, captured the essence of his admirable subject when he wrote: “In the 1880s, she pioneered the development of ‘detective’ or ‘stunt’ journalism, the acknowledged forerunner to full-scale investigative reporting.”

Born Elizabeth Jane Cochran on May 5, 1864 to Michael Cochran and Mary Jane Cummings, both of whom were of Irish descent, Bly had the distinction of being born into a town renamed Cochran Mills in honor of her father, a local judge. She was called “Pink” as a child, that being the color her mother usually dressed her in.

One of fourteen children, Bly and her family were thrown into disarray after her father died suddenly when she was just six years old. Her mother’s subsequent marriage ended in divorce after her husband turned out to be an alcoholic and wifebeater. When she was 15, determined to be a teacher, Bly enrolled at the Indiana Normal School in western Pennsylvania. After only one term, however, her money ran out.

At the age of 22, Bly had a letter published in the Pittsburgh Dispatch, which impressed the editors and earned her a job with the publication. As a prospective journalist for Joseph Pulitzer’s New York World, she later posed as a mental patient in a New York institution, publishing her experiences in an explosive story which led to reform in mental health care.

“People in the world can never imagine the length of days to those in asylums,” she wrote poignantly. “They seem never ending, and we welcomed any event that might give us something to think about as well as talk of.”

Bly’s article provided good insight into the logic of her thinking. “Take a perfectly sane and healthy woman,” she wrote, “shut her up and make her sit up straight from 6 a.m. to 8 p.m. Do not allow her to talk or move during these hours, give her nothing to read, let her know nothing of the world or its doings, and see how long it will take to make her insane.”

She added: “The insane asylum on Blackwell’s Island is a human rat-trap. It is easy to get in, but once there it is impossible to get out…I had looked forward so eagerly to leaving the horrible place, yet when my release came and I knew that God’s sunlight was to be free for me again, there was a certain pain in leaving. For ten days I had been one of them. Foolishly enough it seemed intensely selfish to leave them to their sufferings. I felt a quixotic desire to help them by my sympathy and presence. But only for a moment. The bars were down and freedom was sweeter to me than ever.” Pulitzer’s response to her story? “Obviously this girl is very suited for this profession,” he told a friend, “and of course I have given her a very large bonus.”

One of the forerunners of modern investigative journalism, Bly was reputed to be a fearless character who would go anywhere and do anything for a good story. Add to that her excellent writing skills and you end up with a world-class reporter.

In 1889, Bly had her fifteen minutes of fame worldwide when she set out to beat the record set by Phileas Fogg in the Jules Verne novel Around the Worm in Eighty Days. Setting out from Hoboken, New Jersey on November 14, and garbed in a checkered coat, she journeyed by boat, train, rickshaw and horse, and managed to beat the 80-day record by just under eight days. Despite the perils of her journey, she said she “would rather go back to New York dead than not a winner.”

The diary of her trip records her impressions of the many cities she visited. She describes London as a city of “dim lights and a gray, dusty shade…[with] some fine buildings [and] beautifully paved streets.” Amiens, France, meanwhile, provided her with the opportunity to meet Jules Verne, the inspiration for her journey. Egypt struck her as an unappealing place, with its hordes of beggars, while in Hong Kong it seemed to her as though “one seems to be suspended between two heavens.”

But it was her arrival back in New Jersey that really struck a chord with Bly, as is obvious from her recollections. “The station was packed with thousands of people,” she wrote, “and the moment I landed on the platform, one yell went up from them…I took off my cap and wanted to yell with the crowd, not because I had gone around the world in seventy-two days, but because I was home again.”

In the aftermath of her record travels, completed when she was just 25, Bly saw a hotel, a train and a racehorse named in her honor.

After her marriage to billionaire businessman Robert Seaman in 1895, Bly retired from journalism. After he died, she lost a lot of her fortune to swindlers. Three years after an unsuccessful attempt to restart her career, she died of pneumonia on January 27, 1922. Fellow journalist Arthur Brisbane, a prominent and much-admired newspaperman, described her as “the best reporter in America.”

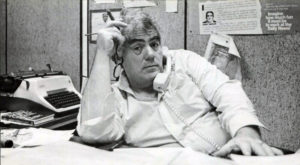

Jimmy Breslin

Newspaperman

“Rage is the only quality which has kept me, or anybody I have ever studied, writing columns for newspapers.”

A New Yorker to his core, Jimmy Breslin has chronicled the lives and injustices of his fellow city folk for over forty years now, and has distinguished himself from dozens of other writers in the process. Like many other columnists of his generation, he has spread his wings in many directions, and is also the author of several novels, screenplays and stage plays.

Born and reared in Queens, he got his start in journalism at the now defunct Long Island Press, and went on to work for such publications as the Journal-American, the New York Herald Tribune, the Daily News and (his current posting) the Long Island-based Newsday. His earlier assignments were mostly sporting ones, but Breslin got his start in column writing in 1963 with the Herald Tribune. Some of the world-changing events he has covered include the assassination of President Kennedy, the civil rights movement of the ’60s and the Vietnam War.

Breslin’s immigrant grandparents hailed from Counties Clare and Donegal, and Village Voice columnist Jack Newfield described him as “classic black Irish, he loves conflict and he acts like each day is the worst day of his life.”

After Breslin’s first wife, Rosemary, died, leaving him to raise six children, he married New Yorker Ronnie Eldridge, a widow with three children. The couple’s hectic family life, and their merging of the Catholic and Jewish traditions, ended up as material for some amusing columns. In 1986, he won a Pulitzer Prize for commentary.

Thomas Cahill

Scholar

“In the 15th century, Edmund Campion described the Irish as ‘religious, frank, amorous, irefull, sufferable of paines infinite. . . delighted with warres, great almes-givers, passing in hospitalitie . . . sharp-witted, lovers of learning . . . ‘ – and they haven’t changed a bit.”

The title alone — How the Irish Saved Civilization: The Untold Story of Ireland’s Heroic Role from the Fall of Rome to the Rise of Medieval Europe — galvanized the Irish and Irish American community. In a century in which the Irish are just beginning to emerge from the national inferiority complex resulting from hundreds of years of oppression, Thomas Cahill’s book gave us further reason to celebrate our own rich heritage. Reading his book, in which he distills centuries of complex history, is as easy and entertaining as sitting around the dining room table after the plates have been cleared and listening to the stories of a dear old uncle.

The best-selling How the Irish Saved Civilization is the first in a prospective seven-volume series entitled The Hinges of History, in which Cahill recounts formative moments in Western civilization. It was followed in 1998 by the second volume in the series, The Gifts of the Jews: How a Tribe of Desert Nomads Changed the Way Everyone Thinks and Feels. The third volume, Desire of the Everlasting Hills: The World Before and After Jesus, is due out this fall.

One of six children born to a middle-class Irish family in the Bronx, New York, Cahill grew up in Queens and attended a Jesuit high school on Long Island. He later became a Jesuit seminarian earning a pontifical degree and becoming proficient in Latin and Greek. He went on to complete his M.F.A. in film and dramatic literature at Columbia University. He also studied scripture at New York’s Union Theological Seminary and most recently spent two years as a Visiting Scholar at the Jewish Theological Seminary of America. He has taught at Queens College, Fordham University and Seton Hall University. He has also served as the North American education correspondent for the Times of London. Prior to retiring recently to write full-time, he was director of religious publishing at Doubleday for six years. He and his wife Susan, also an author, divide their time between New York and Rome.

Rachel Carson

Earth Angel

“It is a wholesome and necessary thing for us to turn again to the earth and in the contemplation of her beauties to know the sense of wonder and humility.”

She is hailed as the mother of the modern environmental movement, and Rachel Carson’s contribution to our current environmental awareness is immeasurable. Her book Silent Spring, published in 1962, revealed to the public the dangers of indiscriminate pesticide use and its hazardous effect on the land and the creatures that live on it. The book prompted President Kennedy to call for the testing of the chemicals mentioned in the book. As a marine biologist, Carson was well aware of the interdependence of all living things and the threat posed by humanity’s lack of awareness.

Carson was born in 1907 in a farmhouse in Springdale, Pennsylvania. It was here that her Irish American mother, Mafia McLean Carson, taught her a love and respect for the land. A schoolteacher and musician, Mafia also fostered in her young daughter a love of literature and encouraged her to consider a career in writing. When Carson enrolled in the Pennsylvania College for Women (later Chatham College) she planned to study English, but all that would change in Mary Scott Skinker’s biology class. She found this science so fascinating, she abandoned her literary aspirations and decided to become a scientist.

In 1929, Carson received a fellowship to study at the Woods Hole Marine Biological Laboratory in Massachusetts. She found the study of the sea captivating. The fellowship was followed by one at Johns

Hopkins University. She went on to earn an M.A. in Zoology in 1932 from the University of Maryland and began teaching there.

Carson’s father Robert died suddenly in 1935 and she was left to find a way to support herself and her mother. She began to work for the U.S. Department of Fisheries in Washington, on a part-time basis writing for a radio show about ocean life entitled Romance Under the Sea. One year later, she became the first woman to take and pass the civil service test and the first full-time female employee of the bureau. Over the next 15 years she would rise from the position of full-time junior biologist to chief editor of all publications of the U.S. Department of Fisheries.

All the while, Carson continued with her own writing and scientific investigation. At the behest of her boss, Carson submitted one of her manuscripts as an article to The Atlantic. The article was entitled “Undersea,” and when the magazine hit the newsstands, the article was so highly praised that Carson was encouraged to put it into a book. The result was the best-seller Under the Sea-Wind.

Carson continued to write government publications throughout the war, taking time off afterwards to write another book with the help of another fellowship. The Sea Around Us also hit the best-seller list, staying there for 86 weeks.

While the public was fascinated by Carson’s scientific explanations and insights, readers were equally drawn to her beautiful writing which seemed more like poetry than science. To Carson this was only natural. “No one could write truthfully about the sea,” she said, “and leave out the poetry.”

When Silent Spring was published, it was viciously attacked by chemical companies; however, her research was vindicated by subsequent government inquiries.

Carson developed cancer and heart disease when she was only 57, and she died in 1964. In 1980, President Carter posthumously awarded her the Presidential Medal of Freedom, saying of her, “Always concerned, always eloquent, she created a tide of environmental consciousness that has not ebbed.”

Maureen Dowd

Columnist

No columnist in America has been as influential as Maureen Dowd over the past decade. She casts a cold eye on Washington affairs and has skillfully skewered president, senators and the high and mighty for so long that her New York Times column has become a fixture on the breakfast tables of the rich and powerful.

It is hard to overestimate her influence. As the eyes of the world zeroed in for more than a year on the impeachment saga in Washington, D.C., it was Dowd whom they turned to for a no-nonsense view of the proceedings. Her acerbic “Liberties” column appears twice-weekly on the Op-Ed page of the Times. She is an equal-opportunities offender, who directs her caustic wit at both Republicans and Democrats on a regular basis.

Her efforts won her a Pulitzer Prize for Commentary in April of this year, for her “fresh and insightful” musings on the President Clinton impeachment scandal. Her reaction was pure Dowd: “To paraphrase Monica Lewinsky’s favorite poet, T.S. Eliot, April is the coolest month.”

The daughter of an Irish cop, Dowd began her journalism career in 1974 as an editorial assistant for the Washington Star. She went on to cover sports, features and metropolitan stories. In 1981 she moved to Time magazine, after the Washington Star closed.

In August 1986, she joined the New York Times as a correspondent in its Washingon bureau. After covering two presidential campaigns, she was appointed a columnist of the paper’s Op-Ed page in 1995. In 1991, Dowd received the Breakthrough Award from “Women, Men and Media” at Columbia University. She also received a Matrix Award from New York Women in Communications in 1994, and was named one of Glamour magazine’s Women of the Year in 1996.

Finley Peter Dunne

Satirist

“Trust everybody, but cut the cards.”

Out of the Chicago Irish community came one of the greatest satirists in American history. In the place where journalism, satire and humor meet, Finley Peter Dunne occupies a special place. As a journalist for the Chicago Evening Post he created the character Martin Dooley, a bachelor saloon-keeper and Roscommon native on Chicago’s South Side, as the central character of his weekly newspaper sketches.

These columns, which recounted in lengthy monologues the opinions of Mr. Dooley, went beyond Irish comic dialogue to focus on the personalities and issues of the day. Created in 1893, the columns spanned more than twenty years and were published in book form.

Until Mr. Dooley, the Irish brogue had been used in 19th century drama, fiction and journalism to portray the stereotypical “stage Irishman,” a demeaning caricature that portrayed the Irish as alternately belligerent and garrulous and always ignorant. Mr. Dooley’s brogue smashed the stereotypes for good. He provoked laughter not because he was ignorant, but because he was so perceptive.

The bright light of Dunne’s satire was laceratingly funny and unforgiving in its exposure of the delusion and hypocrisy of Chicago’s political and social leaders: “Jawn, niver steal a dure mat. If ye do ye’ll be invistigated, hanged, an’ maybe rayformed. Steal a bank, me boy, steal a bank.”

Dunne was born in Chicago’s West Side in the shadow of Old Saint Patrick’s Church on July 10, 1867. As a youth he was encouraged to read and develop intellectually by his mother, Ellen Finley Dunne, and his older sister, Amelia, a teacher in the Chicago public schools. He graduated from high school in 1884 and took a job as an office boy and cub reporter for the Chicago Telegram. Eight years and five jobs later, he was the editorial chairman at the Chicago Evening Post, where, at the age of 26, he created Martin Dooley.

In 1898, the popularity of Mr. Dooley’s satiric perspective on the Spanish-American War led to national syndication and the publication of his first book of selected columns. Dunne moved to New York in 1900 and became one of the most popular humorists of his day. But it is widely agreed that the Chicago Dooley pieces remain his best work, where the Irish oral tradition and the written word come together to preserve the cultural memories and mores of the Chicago Irish at the end of the last century. Dunne died in New York City on April 24, 1936.

Jim Dwyer

Columnist

A trio of New York Irish journalists — Jimmy Breslin, Pete Hamill and Jim Dwyer — have profoundly changed the way newspaper columns are written. Where once columns were either think pieces or puffery of the rich and powerful, Breslin, Hamill, and Dwyer have pioneered a “man on the street on the side of the little guy”-style that has transformed modern journalism.

To New Yorkers the fact that Jim Dwyer is responsible for the first bus and subway fare reduction is reason enough for his inclusion as one of the top Irish Americans of the century. In October 1997, his front-page disclosure of a multi-million dollar surplus — initially denied by the government — forced state officials to roll back the fares.

To the rest of the world, he is simply one of the best journalists of the century, and his two Pulitzers prove it. He won the prize in 1995 for commentary and shared the prize in 1992 for metropolitan reporting. And the fare reductions are not the only way his writing has directly benefited the lives of Americans. He set off a national media stampede with columns exposing sweatshop conditions in a 38th Street garment factory where the Kathie Lee Gifford clothing line was manufactured. The uproar that ensued led to new legislation to protect the working poor.

To Irish Americans, he is even more. He is the source of factual, compelling reports on the state of Northern Ireland. In 1994, he traveled to Northern Ireland and broke the word that a new IRA ceasefire was likely to be declared when the rest of the international media was predicting a civil war. His commitment to balanced reporting has led him where few American journalists have gone before — he once turned up at a street beer-bash in a loyalist neighborhood in Belfast. The residents were astonished — they had never met an American journalist before.

In 1997, he presented a moving yet clear-eyed account of the life and death of Bernadette Martin, an 18-year-old Catholic who was murdered in her sleep for loving a Protestant.

Dwyer joined the Daily News in 1995. Before that he worked for more than 11 years at New York Newsday as an investigative reporter, courthouse reporter, subway columnist and general columnist. He has reported from England, Ireland, Israel, Italy, Spain and Sweden.

A first-generation Irish American (his mother and father are from Counties Galway and Kerry respectively), Dwyer attended Fordham College and Columbia University. He is the author of two acclaimed books, Subway Lives and Two Seconds Under the World, an account of the World Trade Center bombing.

He and his wife, Cathy, live in New York with their two daughters, Maura and Catherine.

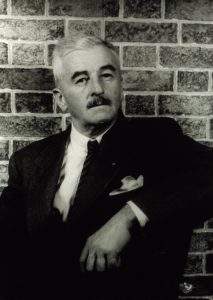

William Faulkner

Voice of the South

“I believe that man will not merely endure: he will prevail. He is immortal, not because he alone among creatures has an inexhaustible voice, but because he has a soul, a spirit capable of compassion and sacrifice and endurance.”

William Faulkner’s is the voice of the South, capturing this region in all its decadence and decay in the years following the Civil War and the anguish surrounding the loss of traditional values as the Old South gave way to the New in all its brash recklessness. Centered around residents of the fictitious Yoknapatawpha county, Faulkner’s novels broke new ground in literature in their use of stream of consciousness and established Faulkner as a master of rhetorical style.

Faulkner was born William Falkner in New Albany, Mississippi in 1897. His father, Murray Falkner, claimed that the Faulkners came to America from Ulster and indeed, Faulkner was a popular name there, particularly in County Derry. When William Faulkner published his first collection of poems The Marble Faun (1924), he reverted to the original spelling of the family name, becoming Faulkner.

After the tenth grade, Faulkner’s education was sporadic. During World War I, he joined the Canadian Air Force, but the war ended before he finished training. He returned to Mississippi where he studied rather fitfully at the University of Mississippi.

A writer since his adolescence, Faulkner published his first book of poetry in his early 20s. A period of travel followed, with Faulkner spending time in New Orleans (where he was encouraged by the writer Sherwood Anderson) and in Europe, before returning to Oxford, Mississippi.

Aside from travel and short stints as a Hollywood scriptwriter to try and earn money, Faulkner remained in Oxford for the rest of his life — writing, fanning and hunting. And there was little reason for him to live elsewhere, for Oxford proved to be fertile soil for his imagination. In two years he published two novels, Soldier’s Pay (1926) and Mosquitoes (1927). These were followed by The Sound and the Fury (1929), the first of the complex, stream-of-consciousness novels that were to become his trademark. That same year he married Estelle Oldham Franklin. Other early novels include As I Lay Dying (1930), Light in August (1932), Absalom, Absalom! (1936) The Hamlet (1940) and Go Down Moses (1942). During these years Faulkner also began to drink heavily.

The difficulty of the novels’ subject matter and narrative style contributed to a decline in Faulkner’s critical reputation during the early 1940s. However, the publication of The Portable Faulkner in 1946 sparked a renewal of interest in his work, and his career took off from there. In 1949, he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature and his Collected Stories won the National Book Award in 1950. In 1954, his novel A Fable won both the National Book Award and a Pulitzer Prize and from 1957-’58, he was writer in residence at the University of Virginia. He continued to publish novels until his death in 1962.

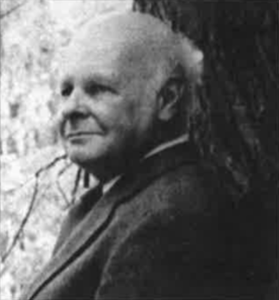

Thomas Flanagan

The Bard

“I am American but when I write Ireland liberates me.”

One day in 1974, Thomas Flanagan sat down to write his first novel. Five years and 502 pages later, the best-selling The Year of the French was published and Flanagan was established as a writer to be reckoned with.

The Year of the French, which recounted the ill-fated Irish rising of 1798, was followed by The Tenants of Time (1988), praised by The New York Times as a “wonderful new book. Every sentence seems to shine.” The End of the Hunt followed in 1993, recounting Ireland’s struggle for independence and the Anglo-Irish treaty that led to the creation of the Free State and civil war.

Meticulously researched and captivatingly told, Flanagan’s novels breathe new life into Irish history and assuredly will keep it alive for generations to come. Like the bards and poets of ancient Ireland, keepers of Ireland’s history who handed it down from one generation to the next, Flanagan’s writing promises to keep Irish history alive and vibrant for future generations.

The son of a physician, Flanagan grew up in a wealthy middle-class home in Connecticut. His grandparents were from County Fermanagh, and it is his grandmother whom Flanagan credits for his early interest in Irish literature and history.

Flanagan’s first samples of creative writing were a far cry from the historical fiction for which he is now famous. From 1948 to 1957, he had several stories published in Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine, even winning the magazine’s best story of the year award in 1957.

Flanagan made his first trip to Ireland in 1962, and in an interview with Irish America he described a feeling of homecoming, “I don’t think I can recall any jolting surprise — just a thickening of the texture of experience. After I arrived in Dublin the taxi driver took me to the center of town. I told him to mm at the Custom House. He turned to me in surprise and said, `I thought you said you had never been here before.’ I hadn’t, I just had an instinctive sense of place.”

A professor of English at the State University of New York at Stony Brook, Flanagan now divides his time between Dublin and New York. He is currently working on a book about the Irish rebel Roger Casement.

James T. Farrell

Wordsmith

“For many of us Americans, there is a gap between our . . . childhood and productive manhood . . . Our beginnings were native, and we must still understand the difference between our present and past.”

In the obituary he penned for himself, James Thomas Farrell described himself as one who “wrote too much…fought too much [and] kissed too much.” Born February 27, 1904 to James Francis Farrell and Mary Daly, Farrell was one of 15 children, and was raised by his maternal grandmother and an uncle.

Best known for his Studs Lonigan trilogy (Young Lonigan, The Young Manhood of Studs Lonigan and Judgment Day), Farrell was a prolific writer who penned some 250 short stories, collected in a variety of volumes. He also published almost 30 novels, and a body of critical essays on literature, politics and society.

Farrell’s South Side Chicago Irish roots were rarely far from his writing, and he always remained very aware of his origins. “I am a second-generation Irish American,” he once wrote. “The effects and scars of immigration are upon my life. The past was dragging through my boyhood and adolescence. Horatio Alger, Jr., died only seven years before I was born. The `climate of opinion’ (to use a phrase of Alfred North Whitehead) was one of hope. But for an Irish boy born in Chicago in 1904, the past was a tragedy of his people…”

The first volume of the Studs Lonigan trilogy was published by Vanguard Press in New York, who attached a warning that the book should only be sold to “physicians, surgeons, psychologists, psychiatrists, sociologists, social workers, teachers and other persons having a professional interest in the psychology of adolescence.”

In 1931 Farrell married Dorothy Patricia Butler. They were later divorced and he married the actress Hortense Alden with whom he had a son. After divorcing Alden, he remarried his first wife, but it was to last just three years. The writer died in New York, at the age of 75, on August 22, 1979, but not before seeing his Studs Lonigan creation dramatized as a six-hour miniseries on television.

F. Scott Fitzgerald

Great Scott

“An author ought to write for the youth of his own generation, the critics of the next, and the schoolmasters of every afterwards.”

Over fifty years after his death, F. Scott Fitzgerald would doubtless be gratified to learn that his writings are still taught in schools all over the United States. The son of a Procter &Gamble salesman and a slightly eccentric mother whose father, Philip F. McQuillan, immigrated to the U.S. from Co. Fermanagh, Fitzgerald was born and raised in the Irish enclave of St. Paul, Minnesota.

He got an early start to his writing career, selling his first short story at the tender age of 13. While he never overtly referred to his Irishness in his work, it remains a strong undertone in many of his books, especially Tender Is the Night and The Great Gatsby.

In a 1933 letter to friend and fellow writer John O’Hara (Butterfield 8), Fitzgerald provided a revealing glimpse at his heritage: “I am half black Irish and half old American stock with the usual exaggerated ancestral pretensions. The black Irish half of the family had the money and looked down upon the Maryland side of the family…So being born in that atmosphere of crack, wisecrack and countercrack I developed a two cylinder inferiority complex.”

Fitzgerald left Princeton before graduating after a brash with tuberculosis, and joined the army in 1917. The following year, while stationed in Alabama, he first laid eyes on the woman who was to become his destiny: Zelda Sayre. On learning that he intended to pursue a career of writing, the single-minded young woman told him she had no intention of marrying a straggling writer, so he had better make money fast. By 1919, Fitzgerald had sold his first novel, This Side of Paradise, but not before amassing some 122 rejection slips and a broken engagement.

True to her word, however, Zelda returned to his side shortly before the publication of his fast book, and the two were married a week after the book was released. Their only child, Frances Scoa, known as Scottie, was born in 1921. The couple had a stormy relationship, and many of their problems were immortalized in Fitzgerald’s writing. By the 1930s, his failing health left Fitzgerald struggling with his writing. However, his creativity returned when he moved to Hollywood in 1937 and took up screenwriting. He died on March 10, 1948.

Doris Kearns Goodwin

Treasure Trove

“Once you start reading, you can never stop.”

Her unrivaled contribution to the body of work on U.S. presidents marks Doris Kearns Goodwin as a writer and historian to treasure. Her book The Fitzgeralds and the Kennedys was on the New York Times best-seller list for over six months. She attributes her interest in the dynamic Kennedy clan to “my lifelong absorption in American history and my special interest in the presidency.”

Born in New York in 1943 to Michael Francis Aloysius Kearns and Helen Miller, Goodwin grew up in Rockville Center, Long Island where, as she wrote in her 1997 memoir Wait Till Next Year, her early years were “happily governed by the dual calendars of the Brooklyn Dodgers and the Catholic Church.” Her maternal grandparents, Thomas Kearns and Ellen Higgins, had emigrated to the States from County Sligo, and her grandfather worked as a firefighter in Brooklyn.

Goodwin worked as an assistant to President Lyndon Johnson during his last year in the White House and later assisted him in preparation of his memoirs. She has also written No Ordinary Time: Franklin and Eleanor Roosevelt, The Home Front in World War II, and Lyndon Johnson and the American Dream, which was described by one New York Times reviewer as “the most penetrating political biography” the reporter had ever read.

Goodwin is a consultant and on-air person for PBS documentaries on LBJ, the Kennedy family and FDR. She is as passionate about baseball as she is about politics and was the first woman journalist to enter the Red Sox locker room. She is married with three children.

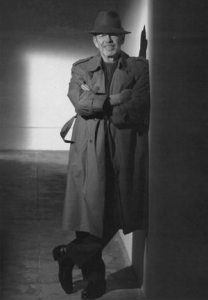

Pete Hamill

Writer

“Our parents, the immigrants, were the products of an interrupted narrative. The story of the American children was a much different narrative.”

One of the great stylists who embodies New York writ large to many, Pete Hamill has the same feel for his city that Studs Terkel had for Chicago. He is also an outstanding and perceptive commentator on the Irish American identity.

Throughout his lengthy career he has been, at various times, a journalist, essayist, columnist, short story scribe, novelist, commentator and editor, but there is one very simple word that perfectly describes Hamill — writer. In his 1995 introduction to a collection of his journalism, the Brooklyn native said writing was “so entwined with my being that I can’t imagine a life without it.”

Born in Brooklyn in 1935 to immigrants from Belfast, Hamill joined the Navy in his youth. After his service he traveled to Mexico, a trip which was to herald a life-long love affair with that country.

As part of a Library of Contemporary Thought series of essays, Hamill’s byline appeared last year on a work entitled News Is a Verb: Journalism at the End of the Twentieth Century. In the piece he detailed his own newspaper career, which began on June 1, 1960, when he was hired to the night roster of reporters at the New York Post.

In the following years he covered the beat at three of the city’s dailies, and has contributed to a dizzying array of national publications and major magazines, including Esquire, Playboy, Conde Nast Traveler and Vanity Fair. Hamill also served two brief editorial stints, in 1997 at the New York Daily News and a five-week term in 1993 as editor-in-chief of the New York Post.

His works include such novels as Snow in August and Loving Women; two short story collections; two collections of journalism and his memoir, A Drinking Life. Last year, his tribute to Ol’ Blue Eyes, Why Sinatra Matters, was hailed by Publishers Weekly as “confident, smart and seamless.”

Choosing him as one of its hall of famers in December 1997, Vanity Fair described Hamill as “a star and staple of New York tabloids and taprooms since the ’60s.”

Hamill has two daughters, Adriene and Deirdre. He lives in Manhattan with his wife, Japanese journalist Fukiko Aoki. The couple also spends long periods of time in Hamill’s beloved Mexico.

William Kennedy

The Albany Author

“I believe that I can’t be anything other than Irish American . . . [It’s] a psychological inheritance that’s even more than psychological. There’s just something in us that survives, and that’s the result of being Irish.”

His books have featured the Quinns, the Phelans, the McIlhennys and the Daughertys — Irish clans every one. He is known as the author who has captured Albany, New York in much the same way that Pat Conroy waxes lyrical about the South. William Kennedy knows very well, however, that his books are less about place than they are about people.

Born in 1928 in Albany, Kennedy is descended on his mother’s side from Monaghan immigrants and on his father’s side from Tipperary stock. After a stint of military service, Kennedy returned home in 1952 and began work with the Albany Times-Union. Four years later he moved to Puerto Rico where he worked on an English-language newspaper.

An eventual move back to Albany saw him back in place at the Times-Union as a freelancer and he took the opportunity to indulge his ambition to write fiction. His first novel, The Ink Truck, was published when he was 40. It was followed by the first two installments of the Albany Cycle, Legs and Billy Phelan’s Greatest Game.

It was another novel, one about Depression-era down-and-outs, that would earn Kennedy his greatest acclaim, and land him a coveted Pulitzer Prize in 1984. Ironweed was subsequently made into a film starting Jack Nicholson and Meryl Streep. Kennedy himself wrote the screenplay for the much lauded film, and for another screen hit, Francis Ford Coppola’s The Cotton Club.

In a 1985 interview with Peter Quinn, Kennedy praised the writings of Edwin O’Connor and his portrayal of Irish America, but added that he felt the Irish America of his experience came down to more than just tension between Church and politics. “I felt I had to bring in the cat houses and the gambling and the violence,” said Kennedy, “for if you left those out you had only a part of Albany.”

“The idealized Irish life of the country club and the Catholic colleges was true enough, but that didn’t have anything to do with what was going on down on Broadway among all those raffish Irishmen. They were tough sons of bitches, dirty-minded and foul-mouthed gamblers and bigots, and also wonderful, generous, funny, curiously honest and very complex people.”

Kennedy is married to Dana Sosa, and the couple has two daughters and a son. He is a regular marcher in the Albany St. Patrick’s Day Parade, and likes to gather with friends, play the banjo and sing Irish songs.

Dorothy Kilgallen

The Voice of Broadway

“I don’t need a psychiatrist. I’m a Catholic.”

Born July 3, 1913 in Chicago to James Lawrence Kilgallen and Mae Ahem, Dorothy Mae Kilgallen was so christened because her name meant `gift from heaven.’ Her paternal grandfather, John Kilgallen, had emigrated from Bohola, Co. Mayo and her maternal grandmother, Delia Conlon, was also Irish born.

Although her mother wanted young Dorothy to be an English teacher — a “nice profession for a girl” — her daughter was far more interested in following Dad’s example. His job as a newspaper reporter seemed infinitely more interesting to her than those of her friends’ fathers, she recalled in later life. “He never suggested that I follow in his footsteps,” she once remarked. “But the footsteps were there, and what other way could I have gone?”

A longtime employee of the Hearst organization, Jim Kilgallen moved his family numerous times, finally ending up in New York. Dorothy’s first published piece of writing appeared in the Brooklyn Eagle when she was 12. She started her first job, with the Evening Journal, a couple of months shy of her 18th birthday. Cutting her teeth on various feature and human interest pieces, Kilgallen quickly moved on to write about murder, kidnapping and other such horrors.

Many reporters who worked the same beat as Kilgallen spoke admiringly of her to biographer Lee Israel, whose Kilgallen: A Biography of Dorothy Kilgallen was published in 1979. A highly talented writer, Kilgallen traded on her girlish looks to wangle her way into places no other woman would have been welcome. Wrote Israel: “Dorothy Kilgallen could out-write, out-wit and out-ruse anyone in yellow journalism.”

Without a doubt one of the biggest stories Kilgallen covered was the 1935 trial of Richard Bruno Hauptmann, who was charged and eventually convicted of the kidnapping and murder of the Lindbergh baby. In September 1936, she was invited by her paper to follow in the footsteps of fellow Irish American reporter Nellie Bly, and compete with two other newspaper reporters in a flight around the globe, traveling at one point on the Hindenburg on its final safe North Atlantic crossing. Even Amelia Earhart sent a telegram wishing her luck.

Although she didn’t win the race, Kilgallen returned to a rapturous reception and a message of congratulations from Eleanor Roosevelt who wrote, “I was rather pleased to have a woman go! It took a good deal of pluck and must have held a good many thrills!” The book Girl Around the World told her story, and a song was written about her called “Hats Off to Dorothy.” Fly Away Baby, a thinly-veiled movie about the race, with screenplay by Kilgallen, was released in 1937.

At the age of 23, Kilgallen changed direction somewhat and moved to California, from where she filed a daily column for the Evening Journal entitled “As Seen in Hollywood by Dorothy Kilgallen.” Working this beat, she competed directly with Louella Parsons, the famous gossip columnist. She also found the time to appear in a movie called Sinner Take All.

On moving back to New York, Kilgallen wrote a Broadway column entitled The Voice of Broadway which soon became one of the most widely-read columns in the country. A radio show sponsored by Johnson &Johnson, and hosted by Kilgallen, had the same name. Reuben’s, a restaurant favored by Broadway types, named a sandwich, their most expensive, after her. Among her beaux at the time were actor Tyrone Power and writer Paul Gallico.

In April 1940 she married stage actor Richard Kollmar and they had three children, Richard, Jill and Kerry. The couple teamed up to host “Breakfast With Dorothy and Dick,” a live daily radio show broadcast from their living room. Kilgallen made her television debut in 1949 on “Leave It to the Girls,” and she subsequently became a regular panelist on “What’s My Line?” a show which served to make her “the most visible and celebrated journalist of her time,” according to Lee Israel.

For her coverage of the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II, Kilgallen was nominated for a Pulitzer Prize and was cited for excellence in reporting by the Silurians. Her coverage of the Sam Sheppard murder trial earned her praise from none other than Ernest Hemingway, who said: “This Dorothy Kilgallen is a good girl.”

In time, Kilgallen and her husband grew apart. He had never attempted to hide his many affairs, and at the age of 44 she began a dalliance with singer Johnnie Ray which was to last just over six years.

When President John F. Kennedy was assassinated in Dallas in 1963, Kilgallen was distraught, remembering a visit to the White House the previous year when the young President had been particularly kind to her son Kerry. After a jailhouse interview with Jack Ruby, she filed no story but began to gather a file on the Kennedy murder. There is speculation that she planned to include the Ruby interview as a chapter in a book she was preparing entitled Murder One. After Ruby’s conviction, she wrote: “The point to be remembered in this historic case is that the whole truth has not been told.” After the Warren Commission Report was released, she became even more determined to solve the mystery behind the assassination. Various sources who spoke to Lee Israel recalled Kilgallen’s excitement that she had “the scoop of the century” with regard to the Kennedy murder.

Kilgallen visited Ireland in the summer of 1965 and attended a ball in Dublin at which Princess Grace of Monaco was a guest. She was found dead in the bedroom of her Manhattan apartment on Monday, November 8, 1965. A death certificate described the cause as “acute ethanol and barbiturate intoxication — circumstances undetermined,” or an overdose of pills and alcohol. It was never determined whether she died by her own hand or by the hand of another, but biographer Lee Israel, after a lengthy investigation, is certain of one thing: there was a cover-up of some sort involved in her death. Her husband Richard Kollmar claimed after her death that he had destroyed the mysterious Kennedy folder.

Frank McCourt

Limerick Leader

“It is an honor to be included among of men and women who haven’t yet produced a saint.”

In Angela’s Ashes, Frank McCourt has written one of the most popular memoirs of the century, in the process redefining the role of the memoir in American literature. Almost three years after the publication of the book,

there’s been a slight slowdown in the excitement surrounding Angela’s Ashes, but the release of Alan Parker’s movie — scheduled for Thanksgiving week — is sure to liven things right back up. Not to mention the planned September publication of `Tis, which picks up where Angela’s Ashes left off.

And if the media hullabaloo has died down somewhat, the fan base is still as strong as ever. The Irish newspapers carried stories in December about a Massachusetts woman so enamored of McCourt’s Pulitzer Prize-winning memoir that she moved to Ireland for a month and a half to secure a spot as an extra in the movie. Ensconced in a Dublin hotel, she ran up a large bill, but had no regrets. “Absolutely, this is the craziest thing I’ve done in my life — and I’d do it again,” said Maureen Quill, speaking to reporters about her long and costly stay.

Fans in Japan might not go to equally expensive lengths, but they certainly believe in paying tribute to their hero on the worldwide web. A website called “The Club of Angela’s Ashes” is lovingly maintained by the Ireland-Japan Friendly Club, and features numerous pictures of McCourt in his native Limerick. Someone has also gone to great lengths to reference a map of the city with marker points for sites included in the McCourt story — and visitors to the site can see where the old Lyric Cinema, beloved of the young Frank and his boyhood pals, once stood. Leamy’s National School, which closed in the 1950s, is also there in all its glory. Hundreds of visitors to the website have recorded their impressions of Angela’s Ashes, with contributions ranging from long (and almost always glowing) reviews to eloquent pleas for a follow-up.

Born in Brooklyn in 1930 to Malachy and Agnes McCourt, McCourt was named for St. Francis of Assisi, and was the oldest of seven siblings, four of whom survived childhood. When he was four years old, the family moved back to Ireland, to his mother’s native Limerick. Years of poverty followed, dotted with the frequent disappearances of their alcoholic father, Malachy Senior.

As soon as he was old enough, Frank hightailed it back to his native New York, and apart from a brief stint in Korea in the 1950s, he’s never left since. To those who wonder whether he identifies himself as Irish, American or Irish American, he cheerfully replies that he’s a true blue New Yorker. A recent move to Connecticut has done little to alter this mindset. His accent, meanwhile, marks him out as a son of Limerick City.

U.S. Education Secretary Richard Riley, who presented McCourt with this publication’s Irish American of the Year award in 1998, said he was convinced that the Brooklyn-born writer had honed his skill throughout his years as “a wonderful teacher” in the New York City public school system. The book spent over 100 weeks on the New York Times bestseller list and there are almost three million copies in print. McCourt is married to Ellen Frey, and it was their honeymoon which inspired him to put pen to paper and begin work on Angela’s Ashes. He has a daughter, Maggie, from his first marriage and two grandchildren.

Alice McDermott

Novelist

“I knew that we were Irish and I knew that Irish was the best thing to be.”

When Alice McDermott won the 1998 National Book Award for Charming Billy, no one was more surprised than she. In fact, she was so sure she wouldn’t win that she did not prepare an acceptance speech, something all finalists are asked to do. Instead she improvised, joking, “I wouldn’t be true to my Irish heritage if I thought this was entirely a good thing…I will clutch onto my Irish humility with great vigor.”

McDermott was born in Brooklyn, New York, and spent her childhood on Long Island, where a sense of Irishness was instilled in her, she recalls. And it is from the Irish American community of her childhood that she draws inspiration. Over the past sixteen years, she has published three other novels: A Bigamist’s Daughter (1982); That Night (1987), a finalist for the National Book Award; and At Weddings and Wakes (1992). Charming Billy explores the nature of faith and family ties among Irish Americans in an attempt to individualize the stereotype of the Irish American alcoholic.

Writing always came naturally to McDermott — she wrote her first novel when she was ten years old — but it was one of her writing professors at the State University of New York at Oswego who really brought home to her that this should be her profession. On handing back her first writing assignment, he informed McDermott, “I’ve got bad news…you’re a writer.”

And her writing is beautiful — intensely visual, sensuous and evocative. Her novels are character rather than plot-driven, and her characters are so finely drawn they remain in your memory like a distant relative. The worlds they inhabit are so detailed, you wonder if you haven’t actually visited these places.

After graduating from Oswego, McDermott enrolled in the graduate writing program at the University of New

Hampshire. It was in graduate school that she met her husband-to-be, a graduate student at Cornell Medical School in New York City. They married a year later and eventually settled in Bethesda, Maryland, where McDermott successfully balances her writing with raising their three children.

And perhaps that is her greatest triumph — she has arranged her life on her own terms, choosing both career and family and refusing to sacrifice one to the other. She has developed the routine necessary to get it all done — she writes when the kids are at school, putting it away when they come home. She also teaches writing one day a week at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore. Her lifestyle is a deliberate choice, not something she has fallen into. “This is a life I’ve arranged for myself,” she points out. “For me, it’s the best way for my children to be happy and for me to get writing done…It’s something I’ve done consciously.”

Eileen McNamara

Columnist

“Is there an Irishman alive who doesn’t have a love affair with words?”

Despite years studying Irish step dancing, Eileen McNamara never won any awards, she says, because she smiled too much. All’s changed now, and smiling is absolutely encouraged, but it’s doubtful that McNamara would seriously consider an offer even from the Lord of the Dance himself to join him on stage.

That’s because she won a far bigger award two years ago — a Pulitzer Prize for a selection of her 1996 columns in The Boston Globe. A reporter for over 20 years, McNamara was installed as a columnist just 18 months before winning the prestigious award.

Her columns have won her much acclaim, focusing on such topics as battered women, juvenile killers and infant mortality. As well as winning the Pulitzer, McNamara also took home the 1997 American Society of Newspaper Editors award for writing, and she was previously awarded a citation by the Robert F. Kennedy Foundation for her commitment to the disadvantaged.

Her first book, Breakdown, a non-fiction examination of the malpractice case against Harvard psychiatrist Dr. Margaret Bean-Bayog, was also published in 1997, to positive reviews from both The New York Times and The Washington Post.

When she’s not writing or spending time with her husband and three children, McNamara teaches a course on media and public policy in the journalism program at Brandeis University.

Her grandparents were Irish, her mother’s family from Malinhead, Donegal and her father’s folks from Ennistymon, Co. Clare.

Margaret Mitchell

Southern Belle

“Death and taxes and childbirth. There’s never any convenient time for them.”

In creating one of the most famous heroines of all time — Gone With the Wind’s Scarlett O’Hara — writer Margaret Mitchell undoubtedly drew on her own Irish roots. She was Catholic on both sides of her family; her Irish ancestors were on her mother’s side. Her maternal great-grandfather, Phillip Fitzgerald, was born in County Tipperary and moved with his family to France shortly after his birth. As a young man, he moved again, this time to the States, where he landed in Charleston. He eventually settled in Taliaferro County, Georgia. One of his daughters, Anne, married another Irishman, Offaly native John Stephens.

According to Mitchell’s biographer, Darden Asbury Pyron, “These two Irishmen [Stephens and Fitzgerald] helped shape the most fundamental stuff of Margaret Mitchell’s imagination.” It is widely believed that Anne Fitzgerald Stephens served as the inspiration for Scarlett O’Hara, although Mitchell always denied any connection between her family and her fiction.

Of her grandfather and great-grandfather, Mitchell said: “They were both Irishmen born and proud of it and prouder still of being Southerners, and would have withered any relative who tried to put on the dog. I’m afraid they were so proud of what they were that they’d have thought putting on the dog was gilding the lily and anyway, they left that to the post-war nouveaux fiche who had to carry a lot of dog because they had nothing else to carry.”

Mitchell endowed her feisty character with an Irish immigrant father, Gerald O’Hara, who named his homestead Tara, after the ancient stronghold in his native Meath. As a child, Mitchell made many visits to the Fitzgerald family homestead in Clayton County, where her mother’s two maiden aunts still lived.

Mitchell will long be remembered for having written the best-selling work of fiction ever produced in America, a book which inspired that beloved movie starring Vivien Leigh and Clark Gable. Within six months of publication, the book sold a million copies, an incredible achievement during the Depression era. It’s a feat all the more remarkable when you learn that Mitchell worked on her opus largely in secret, and was reluctant to show it to anybody.

After graduating from college, Mitchell worked for several years as a feature writer for the Atlanta Journal. She won a Pulitzer Prize for Gone With the Wind. She died on August 11, 1949, not long before her 48th birthday, after being struck by a taxi in downtown Atlanta.

John Montague

Versemaker

“At times I see it, present as a bright day, or a hill, the only way of saving something luminously as possible.”

“I began to read John’s poetry in what was for me the annus mirabilis of 1962-63, the year when I came alive to the excitements of reading contemporary Irish and British poetry and was overcome by the strong desire to write poems of my own, a desire that both ravishes and frustrates you at one and the same time. I felt an almost literal quickening in my bones in those days as I read for the first time poems that brought me to my senses and to a renewed sense of myself in marvelously invigorating ways.

These were poems that would stay with me for a lifetime, such as Patrick Kavanagh’s “The Great Hunger,” Ted Hughes’ “The Thought Fox” and “View of a Pig,” R.S. Thomas’s “Evans” and “Iago Prytherch,” and John Montague’s “The Water Carrier” and “Like Dolmens Round My Childhood The Old People.” These were also the years when John Montague’s essays and reviews were appearing and establishing a home-based critical idiom that was bracing and clarifying, as in his important early review essay (in Poetry Ireland) on the poetry of John Hewitt and his reappropriation of Goldsmith’s “Deserted Village” as an Irish poem in the famous “Dolmen Miscellany of Irish Writing.”

Here was somebody sketching out a way of “bringing it all back home,” prefiguring the Hibernocentric rereading of Anglo-Irish literature which the academic critics would be engaged upon in the decades to come.

Montague’s poems and individual lines in his poems have attained for many of us “that dark permanence of ancient forms” which shadowed his own imagination as he grew up in Garvaghy. There he became aware of the sound a wound makes, of the stress of violence.

But there too he became capable of surmounting all legendary obstacles, of discovering the only possible way of saying something as luminously as possible, of expressing the small secrets of childhood and the life-anchoring memories of erotic experience.

Montague’s poetry has been fit to take the strain of the great historical and political difficulties we have faced in common and to register with honesty and delicacy the most intimate felicities and desolations which we all know (and can only know) alone. The poems have become part of the memory of who and where we have been. They are a “source, half-imagined and half-real,” and what John once said in an early poem about his musician uncle can now be said about himself: he is one of those through whom succession passes.”

– Nobel Laureate Seamus Heaney, writing in Magill magazine on the occasion of Montague’s 70th birthday.

John Montague was born in Brooklyn, New York in 1929, the son of immigrants from County Tyrone. His family returned to Northern Ireland when John was still a child, and because of financial hardship, decided to foster young John out to his father’s two maiden aunts seven miles away.

Returning to a homeland he had never seen, being sent away by his family, and struggling with the shame of a childhood speech impediment all combined to create in the young boy a sense of displacement that would later figure in his poetry as he struggled to find his place within his own family and within Ireland. In his essay “The Complex Fate of Being American-Irish,” he states, “My early poems were attempts to do justice to that world I had returned to, its Scotch, Irish speech patterns, its long history.”

After earning his bachelor’s and master’s degrees from University College Dublin, he completed an M.F.A. degree at the University of Iowa. He was the Paris correspondent for The Irish Times before beginning his career as university professor teaching at universities in France, Ireland, Canada and the United States.

Currently, he is writer-in-residence in the New York State Writer’s Program at SUNY-Albany. He is the recipient of numerous prizes and awards, including the 1995 American Ireland Fund Literary Award and his nomination as Ireland’s Professor of Poetry. He has edited two volumes of Irish poetry and published nine volumes of his own poetry. His collected poems were published in 1995.

Eugene O’Neill

Master of Words

“Man’s loneliness is but his fear of life.”

“You write like an Irishman, not an American,” was the ultimate compliment that the great Sean O’Casey paid Eugene O’Neill. James Joyce concurred, once remarking that O’Neill was “thoroughly Irish.” In a letter to his son, O’Neill himself said, “The critics have missed the important thing about me and my work. The fact that I am Irish.”

Though Eugene O’Neill was born in New York, his father instilled in him a great pride in his pure Irish heritage.

James O’Neill emigrated with his family from Kilkenny, and his wife’s parents came from Tipperary.

O’Neill’s first experience of the theater came when he accompanied his parents on tour and watched his father star in the play adaptation of The Count of Monte Cristo. O’Neill’s own plays dealt with topics American theater-goers were not used to: racial discrimination, the mistreatment of workers, and characters whose dreams were lost, as in The Iceman Cometh.

That play, a daring experimental work which earned him one of his four Pulitzer Prizes, looked for meaning in modern life, and the power behind people and their actions. When it was revived this year on Broadway, starting Kevin Spacey in the title role, the play proved O’Neill’s worth as a playwright, being as relevant now as it was when it premiered fifty years ago.

O’Neill is credited by some historians as single-handedly establishing serious American drama, and is the only American playwright to have won the Nobel Prize in Literature (1936).

His work turned autobiographical with A Long Day’s Journey into Night, his final play, which allowed him to turn his tumultuous childhood around, and to finally approach his family, he said, with “deep pity, understanding, and forgiveness.”

After a life filled with addiction, depression, sickness, divorce, and death, O’Neill died in Boston in 1953.

Mary Flannery O’Connor

Woman of Words

“I don’t deserve any credit for turning the other cheek as my tongue is always in it.”

Deserving of her reputation as one of America’s most important Southern writers of fiction, Mary Flannery O’Connor was lost to the world at the age of 39. During her all-too-short life, she produced two collections of short stories and two novels, but many writers who’ve lived twice as long have not come close to the literary perfection that O’Connor attained.

Born on March 25, 1925 in Savannah, Georgia, Flannery O’Connor (she dropped the Mary after graduating from Georgia State College in 1945) constantly returned to Christian and Catholic imagery in her work, hardly surprising given her devout Roman Catholic roots. Her maternal great-grandfather took part in the first Catholic Mass in Milledgeville, Georgia, while her paternal great-grandfather left Ireland in the 1830s and set up a wagon manufacturing business in Savannah.

O’Connor lost her father days before her 16th birthday to disseminated lupus erythematosus, the same disease that was to kill her some 23 years later. She honed her writing skills while editing her college’s literary magazine, and was subsequently accepted to the University of Iowa’s graduate journalism program. The director of the university’s writing workshop recognized her talent and encouraged her to persist. At the age of 21, she sold her first short story, thus beginning her writing career.

In later years, after extensive hospital treatment for her illness, O’Connor lived with her mother on a farm called Andalusia, a few miles outside Milledgeville. Her frail health made travel difficult, and she was largely house-bound, but continued to receive and enjoy visitors. She also continued to write, devoting her mornings to her craft.

O’Connor’s first novel Wise Blood was published in 1952, followed by her short story collection, A Good Man Is Hard to Find and Other Stories (1955), and a second novel The Violent Bear It Away (1960). Her final collection of stories, Everything That Rises Must Converge, was published after her death. Two of her stories were adapted for television, and noted director John Huston made a film version of Wise Blood. O’Connor’s work also made it onto the stage. She and her writing became the focus of thousands of articles, books and dissertations. She died August 3, 1964, and is buried in her beloved Milledgeville, Georgia, alongside her parents.

John O’Hara

Novelist

“Socially, I never belonged to any class, rich or poor. To the rich I was poor, and to the poor I was poor pretending to be rich.”

John O’Hara once described himself as “the hardest working author in the U.S.” and his body of work remains a testament to that. In a career that spanned 35 years, O’Hara published over thirty novels and collections of short stories. Some of his more popular novels include Appointment in Samarra, Butterfield 8, and Pal Joey.

His extraordinary ability to tell a good story — capturing people and events realistically, especially in his short stories — has influenced such prominent writers as John Cheever, John Updike, Raymond Carver and Richard Ford.

O’Hara’s artistic vision and his keen journalistic eye were indelibly shaped by the fact that he was Irish American. Born in Pottsville, Pennsylvania in 1905 to Dr. Patrick H. O’Hara and Katherine Delaney, he never really gained acceptance into the WASP local aristocracy in spite of his respectable “nouveau riche” background. It was this lack of acceptance, the sense of being on the outside looking in, that developed in O’Hara an eye for people’s behavior: the way they spoke, dressed, what cars they drove and how they lived. In fact, his career could be described as being dominated by a kind of social insecurity; like his contemporary F. Scott Fitzgerald, he longed for acceptance by the Ivy League elite, but unlike Fitzgerald, he never attained it.

Instead he wrote about their lives with a mixture of resentment and envy. Even though he would go on to gain fame and fortune as a writer and travel in the best literary circles, Pottsville, immortalized by O’Hara as the fictitious town Gibbsville, remained a major focus of his imaginative efforts.

O’Hara’s educational history was less than stellar. While he dreamed of the Ivy League, he hardly conformed to anyone’s standard of the model student. He was dismissed from Fordham Preparatory School in 1921, and from Keystone State Normal School the following year. After being chosen as class valedictorian at Niagara Preparatory School in 1924, he was not allowed to graduate. Still, his writing spoke for itself, and he went on to a successful career in journalism.

The course of O’Hara’s personal life did not run smoothly either. In 1931, he married Helen Ritchie Petit. They were divorced two years later. In 1937, he married Belle Wylie. This union produced his only child, Wylie. Belle died in 1954, and one year later O’Hara married Katharine Barnes Bryan, with whom he remained until his death in 1970 in Princeton, New Jersey.

While O’Hara certainly has his detractors who write him off as a minor author, he is undergoing a vindication of sorts in a renewal of interest in his work. His more popular novels are back in print, three biographies have been published, and his short fiction is now the subject of scholarly study.

Anna Quindlen

Writer

“Familiarity breeds content.”

Actress Meryl Streep received rave reviews last year for her touching portrayal of a cancer-stricken mother in One True Thing, but in one interview she gave full kudos for the character to Anna Quindlen, the woman who wrote the book on which the movie was based.

Quindlen has long been praised for her writing skills, beginning with her “Life in the 30s” columns for the New York Times in the 1980s. Two years as an Op-Ed columnist for the Times followed, and many of Quindlen’s avid readers were devastated when she quit in 1994 to become a full-time novelist. The column, which appeared twice weekly, won her a Pulitzer Prize for commentary in 1992.

Her first novel, Object Lessons, spent time on the New York Times best-seller list when it was published, and she followed up with two more best-selling novels, One True Thing in 1994 and Black and Blue in 1998. Writer Alice Hoffman called Quindlen “a national treasure,” while New York magazine once referred to her as “the laureate of real life.”

Quindlen has three non-fiction books to her credit — two of them are collections of her columns, Thinking Out Loud: On the Personal, the Political the Public and the Private and Living Out Loud. She is also the author of two children’s books, Happily Ever After and The Tree That Came to Stay.

In a 1991 interview with this publication, Quindlen spoke fondly of her Irish roots, saying, “In my family you can’t just say, `I’m Anna Quindlen.’ It’s very, very important to say, `I’m Anna Quindlen. I’m Irish.'” Her paternal ancestors moved to this country in the early 1800s. She and her husband, attorney Jerry Curvatin, live in New Jersey with their three children.

Editor’s Note: This article was originally published in the November 1999 issue of Irish America. ⬥

Leave a Reply