Reverend Francis Duffy

Fighting Father

“If I’ve helped anyone become a better man and he loves me for it, that’s my Distinguished Service Cross.”

Beloved pastor and battlefield legend, the Reverend Francis Patrick Duffy, also known as “Fighting Father Duffy,” was truly a man of the people. From the rarefied world of academia to the trenches of World War I France to the mean streets of New York, Father Duffy moved effortlessly, earning the love and respect of all he encountered along the way.

Canadian by birth, Duffy moved to New York at the age of 22 to teach at St. Francis Xavier College, quitting shortly thereafter to join a Catholic seminary. He was ordained in 1896 and was assigned by his superiors to Catholic University for more graduate study. Two years later he was sent to Dunwoodie, the seminary in Yonkers, to teach psychology and logic.

While teaching, he also worked as founding editor for the New York Review, designed to acquaint readers with the new work of European and American theological and biblical scholars. He was sent to the Bronx in 1912 to develop a new parish, the Church of Our Savior. In the meantime, he also became chaplain for the “Fighting” 69th, the famed New York National Guard unit, part of the 165th Infantry. When the United States entered World War I in 1917, the 165th was sent to France and Father Duffy went with them. He was 46 years old.

During 180 days of combat that claimed the lives of 900 men, Father Duffy was on every battlefield. After every battle, he would walk the fields, collecting metal identification tags from bodies, hearing the last words of the dying, giving absolution and helping to bury the dead. One officer recalled seeing Duffy burst into tears as he bent over a dead soldier. When asked why, he replied, “I baptized him as a baby.”

Duffy’s bravery under fire prompted General Douglas MacArthur, the U.S. Chief of Staff, to consider promoting the chaplain to colonel and placing him in command of the division.

His bravery during the particularly bloody battle at the Oureq River won him a decoration, and his citation read, “Despite constant and severe bombardment with shells and aerial bombs, he continued to circulate in and about two aid stations and hospitals, creating an atmosphere of cheerfulness and confidence by his courageous and inspiring example.” He was also proposed for the Medal of Honor, the nation’s highest award for bravery, but he declined the honor.

When he returned to New York in 1919, Duffy was assigned as pastor of Holy Cross parish in Times Square where he became deeply involved in educational issues and fostering ecumenical dialogue and the discussion of church and state relations. Living in the heart of the theater district he befriended such theater luminaries as Spencer Tracy, John Barrymore and George M. Cohan.

When Father Duffy died in the summer of 1932, thousands of New Yorkers, both Protestant and Catholic, went to pray on the steps of Holy Cross Church. More than 20,000 filed past his coffin to pay their last respects. He was given a military funeral and the Mass was held at St. Patrick’s Cathedral instead of Holy Cross because the diocese believed he belonged to the whole city, not just Holy Cross parish.

Five years later, New York honored his memory by erecting his statue at 43rd Street and Broadway in a square beating his name.

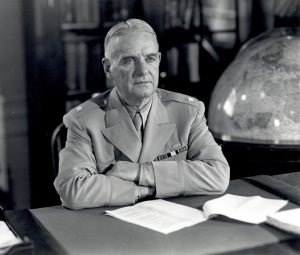

William “Wild Bill” Donovan

Fighting Irish

At one time he had the intention of studying for the priesthood, but William Joseph Donovan ended up having a far more colorful and varied life. A lawyer, a diplomat, a military man and a public representative, he lived his 76 years to the fullest.

Born in Buffalo, New York on January 1, 1883 to Timothy Patrick Donovan and Anna Lennon, “Wild Bill” graduated Columbia University in 1907 with a law degree, and subsequently opened his own firm in his native city.

During the First World War he served in the National Guard and was stationed on the Mexican border. As a colonel in the New York 69th Regiment (he was commander of the “Fighting Irish”) he was posted overseas to France, quickly emerging as a heroic officer, for which he received the Distinguished Service Cross, the Distinguished Service Medal, and the Congressional Medal of Honor.

In the postwar years, Donovan turned to politics, and in 1922 he was appointed U.S. Attorney for western New York. Two years later, he became U.S. Assistant Attorney General. A long and successful career as a diplomat was to follow, and Donovan spent time in Libya, Spain and England, all at the behest of the U.S. government.

Following a request from President Franklin D. Roosevelt, he became deeply involved in the running of the Office of Strategic Services (OSS), the forerunner of the Central Intelligence Agency. His OSS involvement led to Donovan’s becoming known as a principal “spymaster” in the U.S.

Six years before his death, Donovan served as U.S. Ambassador to Thailand. Failing health forced his retirement from public service. He died in Virginia on February 8, 1959.

Audie Murphy

Soldier/Actor

“We have been so intent on death that we have forgotten life.”

For the most decorated U.S. soldier in history, Audie Murphy certainly had a hard time getting into the army. When he tried to join at the age of 17, he was rejected as being too small. Undaunted, he tried again and was accepted in the summer of 1942. Murphy proved to be a fierce warrior: when he left the army in 1945 he had been awarded an astounding 37 medals: eleven for valor, including the Distinguished Service Cross, two Silver Stars, four Purple Hearts and the Congressional Medal of Honor.

His later fame and glory belied his difficult upbringing. Murphy was born in Texas, the son of Irish American sharecroppers. By the age of five, he was out working in the cotton fields under the broiling Texas sun. The Murphy family lived on the brink of impoverishment and sometimes lived in boxcars provided by social service organizations. There were twelve Murphy children, but three died young.

Matters were made worse by Audie’s father, Emmet, or Pat, an alcoholic who would periodically leave the family for months at a time. He finally left the family for good in 1940, when Audie was 16. One year later, Audie’s mother died. She was only 49. Years later, Audie would say of his childhood, “I never had just `fun.’ It was a full-time job just existing.”

Once in the infantry, Murphy quickly distinguished himself as an exemplary soldier. He earned his first decoration, a bronze star, in February, 1943, after destroying a German tank during night patrol. He received the majority of his decorations during the Allied invasion of southern France in August, 1944.

But the climax of his military career occurred on January 26, 1945. Murphy’s company, down to only 18 men and supported by two tanks, encountered six German tanks supported by 250 German infantrymen. One Allied tank got stuck in a ditch, while the other took a direct hit and burst into flames. Murphy ordered his men back under cover, then jumped on the burning tank and trained the machine gun onto the Germans. At the same time, he directed American artillery fire over his field telephone. After half an hour, Murphy had killed 50 Germans and had repulsed the German attack. For this incredible act of bravery and dating, Murphy was awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor, the highest military honor.

After Murphy returned to the States in 1945, it was only a matter of time before Hollywood called and he launched a career in the movies that lasted into the 1960s. Still, haunted by ghosts of his childhood and wartime trauma, happiness eluded him. He suffered nightmares, gambled compulsively and his emotional volatility sometimes made him difficult to work with. He died in 1971, at the age of 47, when the small plane he was flying in crashed on a flight between Georgia and Virginia. He was buried in Arlington National Cemetery, and to this day, only John F. Kennedy’s grave is visited by more people.

Steven McDonald

Hero Cop

When Steven McDonald appeared this summer at the Irish memorial Mass in New York City for John F. Kennedy Junior and the Bessette sisters, there was a prolonged round of applause for the young cop, wheelchair bound since a tragic shooting in 1986. In the years that followed the shooting, McDonald has proven that physical limitations do not have to be perceived as psychological restrictions, and he has transcended the confines of his wheelchair in ways an able-bodied person can only watch and envy.

McDonald made the headlines in the summer of 1986 when he was shot and paralyzed during an attempt to break up a robbery in Central Park. He was the sixth member of his family to join the ranks of New York’s Finest, and he is still on the force as a detective.

His wife Patti Ann, who was pregnant at the time of the shooting, is a familiar face alongside McDonald’s at various Irish events and charity functions, and the two work tirelessly to educate others about the work that police officers do, and about the importance of forgiveness. McDonald had long since publicly forgiven his own attacker, who was killed in a motorcycle accident three days after being released from prison.

McDonald’s ancestors hail from Counties Laois and Leitrim, and he is deeply committed to a number of Irish causes. He and his wife have one son, Conor. They live on Long Island.

James Brady

Crusader

Since the Brady Law went into effect on February 28, 1994, it has stopped an estimated 100,000 convicted felons and other prohibited purchasers from buying a handgun. Every day the law keeps guns out of the hands of dozens of felons. It took seven years to bring this law into being, and the driving force behind this effort was Jim Brady.

We might never have heard of Brady if he hadn’t been in the wrong place at the wrong time. In 1981, he took a bullet meant for President Ronald Reagan. Lodged in his skull, the bullet left Brady permanently disabled — he has difficulty walking and lives in constant pain.

But instead of becoming bitter, he and his wife Sarah focused all their energy on handgun control. Because of their tireless efforts and in spite of a huge, well-organized gun lobby, the Brady Law now imposes a seven-day waiting period for anyone who wishes to buy a gun. In a country where the threat of handgun violence continues to grow, Irish Americans, and indeed all Americans, owe their thanks to James Brady for his efforts to protect the American family.

The Sullivan Brothers

Patriots

In kinder circumstances we might never have heard of the Sullivan brothers. The five fun-loving, hard-working Irish American brothers from Iowa would have settled down, married, raised families and died at ripe old ages in peaceful anonymity. However, their intense loyalty to their friends and to one another proved to be their undoing. As a result, The Fighting Sullivans will be remembered for generations as having made the ultimate sacrifice in the name of patriotism.

The five boys were born to Thomas Sullivan, a second-generation Irish American, and Alleta Abel, also descended from Irish stock. None of the brothers finished high school, which was not uncommon at the time, and they all found work in the local meat packing company.

When the five brothers — George, Francis, Joseph, Madison (Matt) and Albert — heard of the death of a friend in the attack on the U.S.S. Arizona at Pearl Harbor, they all determined to enlist, even though the two older brothers, George and Frank, had already completed tours of duty with the Navy.

The brothers had one condition on enlisting — that they be allowed to stick together. The Navy agreed and the Sullivan brothers were sworn in on January 3, 1942. Not one was over the age of 30 — George, the eldest, was 27 and Albert, the youngest, was only 19.

All five brothers were stationed on the U.S.S. Juneau which was sent in late 1942 to reinforce Guadalcanal, an island the Marines were trying to wrest from the Japanese.

In a battle with the Japanese, the Juneau was destroyed by a torpedo, killing nearly everyone on board. A handful of survivors remained clinging to life rafts, including the last Sullivan brother, George. One night George decided to take a dip in the water. While swimming away from his raft, he was pulled under by a shark. The brothers were reunited in death.

The boys’ deaths rocked the nation, and there was a huge outpouring of publicity and sympathy toward the Sullivan family. Their parents, accompanied by their only surviving child Genevieve, mustered their courage, giving radio broadcasts, and making public appearances at ship yards and war plants urging more production to help other sons still fighting.

In April 1943, Mrs. Sullivan christened a new destroyer, U.S.S. The Sullivans at the Bethlehem Steel Shipbuilding Yard in San Francisco.

Two months later, Genevieve Sullivan, the last Sullivan child, joined the WAVES. While as a woman she would never see combat, she remains a symbol of one family’s undying patriotism in spite of unimaginable loss.

The memory of the five Sullivan brothers lives today in the Sullivan Law which prohibits siblings from serving on the same ship. Their story also provided part inspiration for last year’s blockbuster movie from Steven Spielberg, Saving Private Ryan.

Editor’s Note: This article was originally published in the November 1999 issue of Irish America. ⬥

Leave a Reply