James Cagney

Screen Giant

“If you listen to the clowns around you’re just dead. Go do what you have to do.”

Born July 17, 1899 on New York City’s Lower East Side, James Francis Cagney was the second of seven children, two of whom died in infancy. His father was a saloonkeeper in the tough neighborhood where many of Cagney’s contemporaries ended up in prison. In an interview with Esquire in 1981, Studs Terkel asked Cagney what kept him from being like them. He replied, “I had a mother who would belt us if we did anything cockeyed.” Still some of the things he said in the movies including “Whattya hear, whattya say?” came from those same streets.

Of his early stage experience he said, “I needed a job, and a fellow told me to go to the 81 st Street Theater. That was how easy it was. I walked in, met the stage manager, and I was doing the job the next morning — dancing singing, and doing female impersonations.”

Cagney gradually worked his way up to bigger and better roles. He toured in vaudeville, and received small parts in dramas and musicals. A stand-out performance in Penny Arcade led to a contract with Warner Brothers. His fifth film, The Public Enemy (1931), secured his spot as one of the studio’s top stars, where he stayed for over 20 years.

Cagney’s command of his characters was unparalleled. His quiet, modest demeanor off screen seemed the antithesis of his explosive, fast-talking, tough-guy roles. On his performance in Torrid Zone (1940) Time magazine wrote, “Cagney…can express a complete characterization with one little gesture.” On preparing a character, Cagney said, “I try to fully realize the man I am playing…I draw upon everything I’ve ever known, seen, heard, or remember.” Some of Cagney’s most memorable films are Angels With Dirty Faces (1938), White Heat (1949) and Yankee Doodle Dandy (1942), for which his performance as song-and-dance-man George M. Cohan won him an Oscar.

Married 65 years to Billie Vernon, whom he met while a chorus boy, James Cagney lived on a farm, staying close to the land from the 1930s to his death on March 30, 1986.

Walt Disney

Mousketeer

“If you can dream it, do it. Always remember, this whole thing was started by a mouse.”

Disney is a household name to millions of families throughout the world, thanks to Walter Elias Disney whose creative genius has been providing children and their families endless hours of entertainment throughout this century. Along with giving us endearing icons Mickey Mouse, Donald Duck and their cohorts, he is also responsible for technical innovations in sound, color and photography in the movies and television. And of course, he is responsible for two of the world’s most famous amusement parks, Disneyworld and Disneyland.

Disney was born on December 5, 1901 in Chicago. His family name is a corruption of the French Huguenot name d’Isigny many of whom, including members of his family, fled to Ireland to avoid religious persecution.

His father, a Canadian of Irish descent — the family roots go back to County Carlow — moved the family to a farm in Marceline, Missouri when Wait was quite young. It was on this farm that he developed the deep love and respect for animals that would become apparent in his films. After Marceline, the family moved to Kansas City.

Walt never finished high school, but worked at several jobs while studying in the evenings at the Chicago Academy of Fine Arts. When he was 15, young Walt resolved to join the Army, creating documents falsifying his age so he could enlist. After working for three years as a driver for the Red Cross Ambulance Corps in France, Disney returned to Kansas City and turned his attention to filmed cartooning.

In 1923, Disney decided to take his chances in Hollywood, and in partnership with his brother Roy, set up a small studio to develop short cartoons. This was the beginning of what would become the Walt Disney empire.

Disney’s best known character, Mickey Mouse, was an instant success when he made his debut in 1928 in the cartoon Steamboat Willie. Disney Studios began churning out Mickey Mouse cartoons as fast as it could, and the adorable mouse won a huge fan base that included King George VI of England, Arturo Toscanini and Cole Porter.

Disney’s creativity was inexhaustible. He first introduced the Technicolor process in film in Flowers and Trees (1932). Five years later he produced the first feature-length cartoon in history, Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (1937).

Snow White was followed in rapid succession by Fantasia (1940), a tour de force in animation, The Reluctant Dragon (1941), Dumbo, and Bambi (1942), Disney’s most successful cartoon ever. Throughout the forties and fifties, Disney Studios produced both cartoon and live-action short and long films including So Dear to My Heart (1948) and Cinderella (1950). In the fifties, Disney branched out into television producing the Davy Crockett series and launching The Mickey Mouse Club.

Disney’s next venture was a huge risk that was greeted with strong opposition by executives at the Walt Disney Company. As he had done with film, Disney now resolved to create something wonderful in amusement parks. Disneyland opened in California in 1955, followed by Walt Disney World in Florida. The lasting success of these amusement parks is a testament to Disney’s vision.

The success of Mary Poppins in 1965 proved that the aging Disney had not lost touch with his child-like creativity and sense of fantasy. Walt Disney succumbed to lung cancer in 1966, but his spirit lives on in the imaginations of children touched by his legacy.

Jackie Gleason

Funnyman

“To the moon, Alice! One more time and it’s to the moon.”

Born in Brooklyn on February 26, 1916, Herbert John Gleason was raised by his mother (who affectionately called him Jackie) after his father abandoned the family when Jackie was eight years old. Young Jackie never stopped to wonder what he would be when he grew up. He wanted to be on stage, to entertain, and after winning an amateur-night competition at fifteen, Gleason was on his way. When he wasn’t emceeing stage shows all over New York, he worked as a master of ceremonies for carnivals, a radio disc jockey, a daredevil driver, and an exhibition diver in the water follies.

Gleason built his career slowly, making five Hollywood films before returning to New York to work in Broadway musicals. He began his television career on Ed Sullivan’s Toast of the Town and with the series The Life of Riley, but it was his brief appearance on DuMont’s Cavalcade of Stars in 1950 that made him an overnight TV sensation. After Cavalcade of Stars, and several big contracts with major TV networks, Jackie returned to Broadway in 1959 and won a Tony Award for Take Me Along, and an Academy Award nomination in 1962 for the film The Hustler.

Although Gleason could neither read nor write music, he released over 20 albums between 1953 and 1969 and wrote the themes for The Jackie Gleason Show and The Honeymooners. Despite 50 years of a wide array of creative achievements, Gleason is best known for a character he played on The Honeymooners — Brooklyn bus driver Ralph Kramden. When his sidekick Art Carney asked why The Honeymooners lasted only one season, Gleason said, “The excellence of the material could not be maintained, and I had too much fondness for the show to cheapen it.” Maybe that’s why those shows have become classics, in constant reruns. He died in Miami, Florida, on June 25, 1987.

Helen Hayes

First Lady of the Theater

“I have Ireland in my blood and every exciting actor or actress that I’ve known has an Irish background. It’s a strange thing but we are performers, we are actors by heritage.”

One might think that Helen Hayes was genetically predisposed to the theater. Her great-great-aunt was the famous Irish singer Catherine Hayes, known as “The Swan of Erin,” and Helen’s own mother dreamt of making a career on the stage.

So it may surprise readers to learn that the most famous stage actress of the century did not want to become an actress. Instead she was pushed into acting by her mother Catherine.

Born in Washington, D.C., in 1900, Hayes first began appearing in amateur productions at the age of five. One production was seen by the comedian Lew Fields who was so impressed with the child’s talent, he told her parents that he would help her if she wanted to become an actress. Neither her father, Francis, nor Helen herself had much say in the matter. Catherine promptly left her husband and moved herself and her child to New York, where Helen was cast in Fields’ Broadway production Old Dutch in 1909.

In many ways, Hayes was robbed of her childhood. A working actress at the age of nine, she also assumed the responsibility of breadwinner for herself and her alcoholic mother. Afraid of losing work, Hayes allowed her producer George Tyler, who made her an adult star in ingenue roles, to exercise an almost tyrannical control over her professional activities.

Her life changed with her marriage to the playwright Charles MacArthur (The Front Page). Though they were complete opposites, the two complemented each other well and Hayes credits him with her growth as an artist. She and Charles had two children, Mary born in 1930 and James, whom they adopted in 1938.

After her marriage, Hayes finally discarded the ingenue and paper-thin movie roles and entered her greatest period as an actress beginning in 1933 with Mary of Scotland. In 1935, she created her masterful portrayal of Queen Victoria in Victoria Regina, a role that required her to age 60 years before an audience. She would go on to perform in the plays of Tennessee Williams, George Bernard Shaw, Eugene O’Neill, Thornton Wilder and William Shakespeare. She was underrated by some critics because her seamless acting emphasized the basic humanity and simplicity of her characters, and lacked any of the posturing of stardom.

Hayes’ move to Hollywood sprang not out of any ambition to further her fame or career, but to stay with her husband who had become one of the highest-paid screenwriters. She received an Oscar for her very first film, The Sin of Madelon Claudet (1938). While she went on to be cast in major productions, she realized these movies were second-rate in story quality to the work she had been doing in the theater.

She decided to quit Hollywood in 1934 after MGM butchered the film version of her favorite stage play, What Every Woman Knows. As she told one reporter, “I don’t think I’m much good in pictures, and I have a beautiful dream that I’m elegant on stage.” Her departure from Hollywood did not prove permanent, however. During the

1950s she appeared in three movies and from the late ’60s to the late ’80s she regularly appeared in movies and in television films. She was awarded her second Oscar for her role as the stowaway grandmother in Airport (1970).

Along with her extraordinary achievements, Hayes also experienced intense personal loss. In 1949, her daughter Mary, herself a promising actress, died of polio at the age of 19. Unable to cope with his sorrow, Charles spent the remaining seven years of his life sinking into alcoholism before dying in 1956.

Hayes turned her grief toward a positive end, helping to create the Mary MacArthur Memorial Fund which raised millions to eradicate polio, as well as becoming the spokesperson for many other charities. Over the years she has garnered such awards as the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the Kennedy Center Honors, two Tonys, an Emmy, a Grammy, the Fred Allen Humanitarian Award from the Catholic Actors Guild, the USO Woman of the Year Award and the Drama League Medal.

In Washington, D.C., the Helen Hayes Awards are given annually for distinguished achievement in the nation’s capital, and several Broadway and regional theaters have been named for her.

A friend of Hayes once said, “One of Helen’s favorite expressions about other people is that he or she `rose above the situation,'” an observation that could easily be made about Hayes at several points in her remarkable life. She died on St. Patrick’s Day in 1993.

Anjelica Huston

Screen Star

“I don’t feel anywhere else in the world the way I feel in Ireland. I feel at home there.“

She brought James Joyce’s Gretta to life in her father’s screen adaptation of Joyce’s short story The Dead, and created the unforgettable Maerose in the 1985 film Prizzi’s Honor, for which she won an Oscar. Anjelica Huston has lit up our screens in many guises through the years, but a part of her is indelibly Irish thanks to the many childhood years she spent growing up on her father’s Galway estate.

In various interviews with Irish America through the years, the most recent just this year, Huston has stressed how important her time in Ireland has been to her and how much those years shaped her life. She attributes her early interest in imaginative pursuits to the decidedly lessglamorous Irish country upbringing, where television and Toys `R’ Us didn’t feature to any extent.

Speaking to this publication in 1995, she said: “I’m completely proud of my Irish background. It’s a nation of poets, a nation of speakers, a nation of communicators. I root for the Irish on any possible occasion. Instantly.”

Having lived in Ireland since she was 18 months old, Huston found it very difficult to leave Galway to attend school in London. Then her Italian-American mother died suddenly in a car accident and she and brother Tony moved back to the U.S. In later years, she and her brother worked with their father on The Dead, an experience she thoroughly enjoyed.

Her many films have included The Addams Family, The Grifters, The Postman Always Rings Twice and The Witches of Eastwick. One of her most recent projects, Agnes Browne, saw her back in Ireland at the start of this year. Adapted from The Mammy, a book by Irish comedian Brendan O’Carroll, the film was directed by Huston, who also played the title role. O’Carroll had nothing but praise for her handling of his work, and Huston explained her interest in the story of a young Dublin widow raising seven children alone by remarking that she was constantly “drawn to survival stories.” The film was screened at Cannes this spring.

Huston made her directing debut in the acclaimed Showtime production Bastard Out of Carolina. She is married to Mexican-American sculptor Robert Graham.

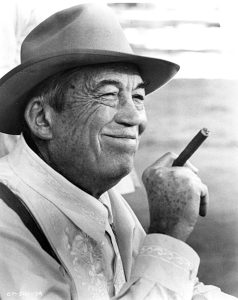

John Huston

The Ambassador

“Nostalgia for Ireland sweeps over me often, not just when I’m working with an Irish cast. I love Ireland and I miss it very much.”

He was a lightweight professional boxer, a stage actor, a member of the Mexican cavalry and a writer, but it is for his unparalleled directing skills that John Huston is best remembered today. He won an Oscar in 1948 for The Treasure of the Sierra Madre, and in a career spanning over four decades he made a total of 30 pictures.

Born in 1906 to actor Walter Huston and Rhea Gore, Huston was raised in Nevada and Missouri where his father worked in engineering. When Huston senior returned to acting on the vaudeville circuit, his son’s

education suffered somewhat, and young John left high school early to become a boxer. By the age of 18 he had followed his father into the theater.

A period of two years in the Mexican cavalry followed, after which Huston became a writer, dabbling in short stories and eventually working as a reporter for the same newspaper that employed his mother. He was next hired by Samuel Goldwyn as a writer, and his first script was for A House Divided.

Stints in England and Paris followed, but in 1938 Huston succumbed to his destiny and returned to Hollywood where he wrote for Warner Brothers. He directed his first film, A Passenger to Bali, in 1939. Two years later, he was assigned to direct The Maltese Falcon, which was to become just one high point in a career full of them. Other notable films included Quo Vadis and We Were Strangers.

Throughout the 1950s and ’60s, Huston’s was a familiar face in Co. Galway where he lived in St. Clerans with his children, and regularly attended local hunting functions. The estate was recently bought and restored by American TV personality Merv Griffin, who named various suites in the impressive house after the Huston family. Huston held Irish and U.S. citizenship during his life, and traveled on an Irish passport.

In a 1987 interview with this publication, Huston traced his long-time passion for the work of James Joyce back to his youth, when his mother smuggled a copy of Ulysses into the States in 1928. The book was banned at the time, but it was to have a profound influence on young Huston. “I’ll never forget reading it,” he told Irish America. “It’s probably what motivated me to become a writer and filmmaker.”

Almost 50 years later, his love for Joyce’s words was immortalized into a remarkable celluloid tribute to the Irish writer with the highly-acclaimed film The Dead. In a bid to “preserve the integrity” of Joyce’s work, Huston insisted on an all-Irish cast, and would have filmed in Ireland if ill-health had not prevented him from traveling that far. Huston died in 1987, not long after completing work on The Dead.

Grace Kelly

Princess

“I hated Hollywood. It’s a town without pity. Only success counts. Anyone who doesn’t have the key that opens the doors is treated like a leper.”

She was known for her icy cool blond poise and her ladylike charm, and when she married Prince Rainier III of Monaco in 1956, it was seen the world over as a fairytale match — the prince had found his beautiful princess.

Born in Philadelphia to Margaret Majer and John Brendan “Jack” Kelly on November 12, 1929, Grace Patricia Kelly was a leading lady long before she met Prince Rainier. Discovered while modeling in New York, she went on to act in almost a dozen feature films. Her first stage appearance occurred at the age of 11, when she acted with The Old Academy Players, an East Falls little-theater group. According to Kelly family biographer Arthur H. Lewis, “Miss Kelly did nothing outstanding there but was respected as a quiet, dependable member of the cast.”

Kelly won an Academy Award in 1954 for her portrayal of Georgie in The Country Girl. Actor William Holden, with whom she starred in that movie, said of her, “With some actresses you have to keep snapping them to attention like a puppy. Grace is always concentrating. In fact, she sometimes keeps me on track.”

Stewart Granger, a co-star on another film, Green Fire, also praised Kelly’s poise. “She has a mental attitude that says, well, if there’s nothing she can do about a bad situation, she’s perfectly calm,” remarked Granger. “If there’s something she can do about it, then she’s not calm. It’s a wonderful philosophy of life.”

As the star of such notable movies as High Noon and High Society, Kelly was the epitome of glamour and grace. She once remarked that she had no intention of becoming “a beautiful but dumb clotheshorse,” adding, “I don’t want to dress up a picture with just my face. If anybody starts using me as scenery, I’ll return to New York.” Director Alfred Hitchcock also chose her to star in three of his best-known works: Dial M for Murder, Rear Window and To Catch a Thief. By the end of 1954, she was the number one female box office attraction in America, receiving more fan mail than any other MGM star.

Said actor Jimmy Stewart: “She has great beauty and a quality that hits you like a cyclone…. She has class. Not just the class of being a lady — I don’t think that has anything to do with it — but she’ll always have the class you find in a really great racehorse.”

Kelly retired from acting upon her marriage to Prince Rainier, and the couple had three children: Caroline, Albert and Stephanie. Her sudden death on September 14, 1982 in a car accident shook her legions of fans who had not stopped hoping for her eventual return to the screen.

During her lifetime, Kelly made several trips to Ireland, and bought her ancestral home in Louisburgh, County Mayo. Her grandfather, John Henry Kelly, had left his native Mayo in the 1860s, landing in Vermont, where he met and married fellow Irish immigrant Mary Anne Costello in 1869. They eventually settled in Philadelphia and had ten children, one of whom was John Brendan, the father of Princess Grace and a champion oarsman. Grace’s brother, John Junior, or “Kell” as he was known, took his father’s athletic prowess a step further. “John Kelly, grandson of an Irish pig farmer…won the Olympic singles gold medal,” his proud sister is recorded as saying years later. Grace’s uncle, George Kelly, won a Pulitzer Prize for his play Craig’s Wife.

Maureen O’Hara

Screen Colleen

“You [have to] stay with what you believe in and what you feel. You cannot sway and swing with the opinion of few who have big mouths. You have to stick with your own values.”

As Mary Kate Danaher in John Ford’s classic film The Quiet Man, Maureen O’Hara has engaged the hearts of viewers the world over for over four decades.

Born Maureen Fitzsimmons on August 17, 1921, in Milltown, Co. Dublin, O’Hara was one of several actors and singers in the family. Her mother was an actress and singer who performed on stage in Dublin, while her father, a clothing retailer, founded Dublin’s Shamrock Rovers soccer team.

O’Hara started her career, as have many other notable Irish actors, with the Abbey Theatre in Dublin. Her role in Jamaica Inn, a film shot in London, led to her discovery by Charles Laughton, who cast her as Esmeralda in The Hunchback of Notre Dame. As well as giving the budding actress her first big break, Laughton re-named her, telling her that the name Fitzsimmons was too complicated for Hollywood.

O’Hara’s versatility saw her cast as everything from a Castilian to a French adventuress in a series of costume epics. She made a total of four films with [John Ford], including How Green Was My Valley and Rio Grande. She and Quiet Man co-star John Wayne teamed up for a further four pictures. She also gave sterling performances in such timeless classics as Miracle on 34th Street. She made a total of 55 pictures in a career which has spanned almost fifty years. Her most recent film was Only the Lonely, in which she starred as the feisty mother of the late John Candy.

In 1998, O’Hara realized a long-held ambition when she became the third woman to lead the New York St. Patrick’s Day Parade up Fifth Avenue. Adoring crowds shouted greetings as she marched along proudly, her trademark red locks shining in the bright sun.

Gregory Peck

Sterling Actor

“The Irish influence has been a big thing in my life – kind of an anchor – it means a lot to me.”

While studying for pre-med, Gregory Peck was bitten by the acting bug and decided to change his direction in life. He enrolled in the Sanford Meisner Neighborhood Playhouse in New York, and upon graduating debuted on Broadway in Emlyn Williams’ play The Morning Star. One year and three plays later, in 1943, he was in Hollywood, starring in Days of Glory, a war movie.

A glorious screen career followed, and in 1962, less than 20 years after that fresh young face had arrived in LA, Peck won an Academy Award for his riveting performance as Atticus Finch in To Kill a Mockingbird. He had previously received four Oscar nominations. In January of this year, he stepped up to a podium yet again, this time to accept a Golden Globe award for Best Supporting Actor in Moby Dick. Peck was greeted with laughter when he deadpanned, “I think I won one of these in 1947 and it was very encouraging. It’s very encouraging now.”

Among his other notable movies are The Yearling, Gentleman’s Agreement, Beloved Infidel, Roman Holiday and The Gunfighter. He also starred in one of the most successful horror films of the 1970s, The Omen.

Peck’s maternal grandmother, Katherine Ashe, a native of Dingle, Co. Kerry, raised her son — Peck’s father — partly in her native county. The young Eldred Gregory Peck, who later dropped his first name, was born in La Jolla, California, on April 5, 1916, and grew up heating stories of his father’s Irish childhood.

Peck is still very active on behalf of a number of worthy charities and organizations. He has helped the American Cancer Society to raise over $50 million, and has established a number of film scholarships at University College Dublin. He lives in Beverly Hills with his second wife Veronique. The couple has a son and a daughter, and Peck also has three sons from his first marriage to Greta Rice.

He has been the recipient of numerous awards, including the Medal of Freedom (1969), Lifetime Achievement Awards from the American Film Institute (1989) and the Lincoln Center Film Society (1992), and the Marian Anderson Award (1999), bestowed annually on individuals who exemplify humanitarian efforts during the course of their life and professional career.

Spencer Tracy

Chieftain of the Screen

“I wouldn’t have gone to school at all if there had been any other way of learning to read the subtitles in the silent films.”

His kind eyes, hard face and gruff honesty map a Celtic landscape. One can easily imagine Spencer Tracy serving as a pagan chieftain and (in true Irish style) making it look easy. There is a sublime offhandedness in every Tracy performance.

Born on April 5, 1900 in Milwaukee, Wisconsin to John Edward Tracy and Carrie Brown, Tracy was educated by Jesuits. Family legend has it that Tracy senior (“a devout, hard-driving, Irish Catholic businessman,” according to Bill Davidson’s book Spencer Tracy: A Tragic Idol) spent the night of his son’s birth getting drunk in all of Milwaukee’s Irish bars.

Tracy came to acting after serving with the navy in the First World War. His performance in a 1929 Broadway drama called The Last Mile so impressed film director and fellow Irishman John Ford that the actor was given the lead in Ford’s next feature, a prison comedy called Up the River (1931), which co-starred Humphrey Bogart.

There were handsomer men on-screen, but none with Tracy’s solid, fatherly warmth. He won two Academy Awards in a row: one for Captains Courageous (1937), the next for playing a priest in Boys Town (1938). A devout Catholic throughout his life (he’d almost entered the priesthood as a young man), Tracy married former actress Louise Treadwell in 1923 and was the proud father of two children, but he suffered terrible pangs of guilt over his love affair with Katherine Hepburn.

When he and Hepburn were teamed to star in Woman of the Year (1942) it was love on sight, and something like emotional stability entered Tracy’s life. Their on- and off-screen romance through such gems as Adam’s Rib (1949), Pat and Mike (1952) and Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner (1967) lasted until his death. His ability to puncture her ballooning pretensions with a silent, impish look was a classic trademark of their comic chemistry.

Whether playing a disabled veteran trying to mete justice in a seedy western town in Bad Day at Black Rock (1955), or a dying political leader in John Ford’s great drama of Irish America, The Last Hurrah (1958), or holding courtrooms in thrall in Inherit the Wind (1960) and Judgement at Nuremberg (1961) Tracy positively embodied the hard wisdom of life.

John Wayne

The Cowboy

“Talk low, talk slow, and don’t say too much.”

“How many times do I gotta tell ya,” he’d say. “I don’t act — I react.” This is as close as John Wayne ever came to a soul-baring confession, and there was no need for him to elaborate. His whole being was invested in his reactions. He could defeat an attacker with a quick gunshot, a right to the jaw or a silent, contemptuous look. He was equally capable in any circumstance — and the camera loved him for it.

Audiences adored him too, and in the decades since his death, John Wayne is not only cherished as an icon of masculine beauty and power, he is celebrated as the greatest reactor the movies have yet produced. Born Marion Michael Morrison, of Irish descent, in Iowa, he won the nickname “Duke” as a teenager after his family moved to Los Angeles. He excelled at football and won a scholarship to USC. His good looks won him bit parts in westerns, at first under the name Duke Morrison.

Born on April 5, 1900 in Milwaukee, Wisconsin to John Edward Tracy and Carrie Brown, Tracy was educated by Jesuits. Family legend has it that Tracy senior (“a devout, hard-driving, Irish Catholic businessman,” according to Bill Davidson’s book Spencer Tracy: A Tragic Idol) spent the night of his son’s birth getting drunk in all of Milwaukee’s Irish bars.

Directors took a shine to him. One early admirer, John Ford, introduced him to Raoul Walsh and, under the name “John Wayne,” he made his debut as the star of a spectacular epic The Big Trail (1930).

What Wayne did over the next eight years remains forgettable, but when Ford starred him in Stagecoach (1939), Wayne became a top star. War films, cop films, costume dramas all followed. In The Conqueror (1956), he drawls unforgettably, “This Tartar woman is for me, and my blood says take her.”

And yet, that same year, he gave one of the great performances of his life in John Ford’s The Searchers (1956), playing an obsessed and quite frightening Indian hunter. His best work is with John Ford: They Were Expendable (1945); She Wore a Yellow Ribbon (1949); The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance (1962) and, of course, that epic Irish movie, The Quiet Man (1952). He won an Oscar for True Grit (1969), directed by Henry Hathaway.

After years of battling cancer, his final film, The Shootist (1976), about a dying gunfighter, constitutes a heartfelt personal statement — offered not so much in words but in deeds. Wayne was a particularly great reactor when looking death in the eye. He made his strength and courage seem like natural reactions to the mysterious fact of his having been born at all.

Editor’s Note: This article was originally published in the November 1999 issue of Irish America. ⬥

Leave a Reply