Maureen Connolly

Little Mo

She was the first woman and the youngest tennis player ever to win the Grand Slam — the four-in-a-row Australian Open, the French Open, Wimbledon and the U.S. Open — and one of only five players to do so. Her name was Maureen Connolly, but to adoring fans she was “Little Mo.”

Born in San Diego on September 14, 1934, Connolly was just 18 years old when she captured the elusive Grand Slam in 1953. She captured the Wimbledon title the year before and after this amazing feat, but a horseback riding accident in the summer of 1954 ended her tennis career prematurely.

After her marriage to Norman Brinker, she moved to Dallas, Texas, where the couple lived with their children. According to her daughter, Cindy Brinker, Connolly was “a devout Irish woman,” who treasured her Catholic beliefs and had an audience with the Pope.

In 1968, anxious to promote her beloved tennis to the best of her ability, Connolly co-founded the Maureen Connolly Brinker Tennis Foundation, an association which continues to be active today in the provision of a myriad of programs and activities for children throughout the U.S. and the world.

Connolly succumbed to cancer six months after the Foundation was established. Ever the tennis devotee, her death occurred on the eve of Wimbledon.

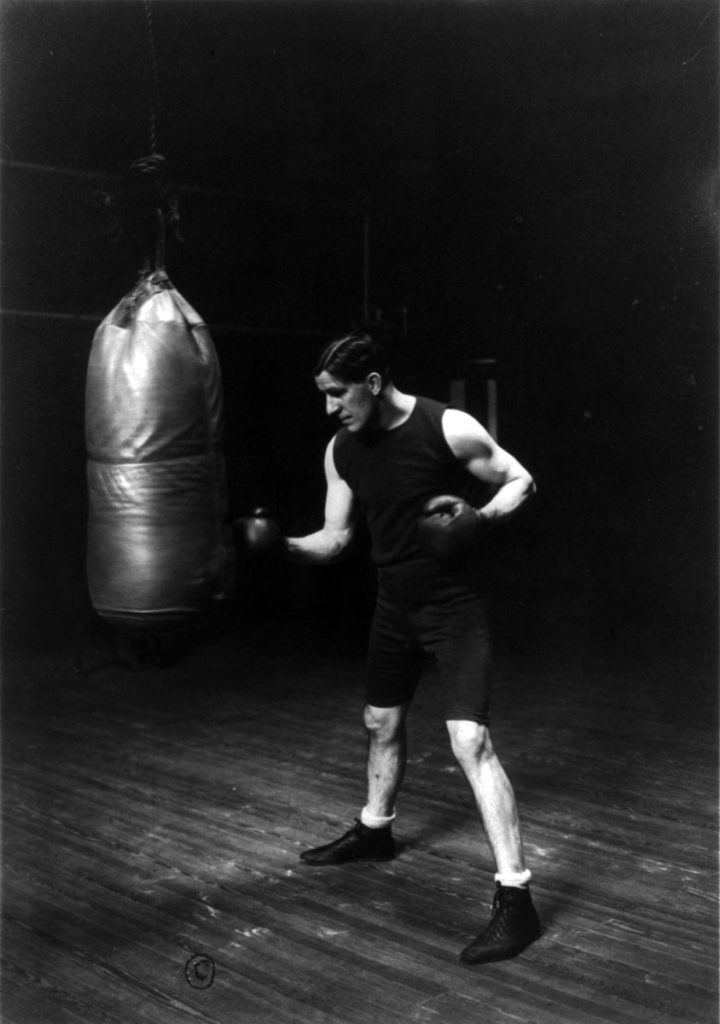

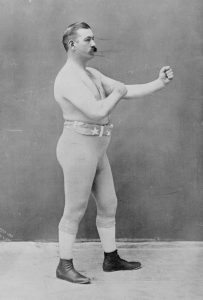

James “Gentleman Jim” Corbett

Fists of Fire

James John Corbett may have swapped a career as a bank teller for that of a prize pugilist, but he never fully shook the gentle manners and business style of dress that earned him the nickname by which he would become known throughout the States.

The son of a San Francisco stablehand, Corbett was a first-generation Irish American on both his mother’s and father’s side, but that didn’t stop boxing fans from taking the side of John L. Sullivan, also Irish American, in the fight which was to catapult Corbett to sporting fame. Held in 1892, it was also the first U.S. World Heavyweight Boxing Championship to be fought with gloves, and the first to be governed by the Marquess of Queensberry Rules.

When Corbett beat Sullivan, he stunned the spectators into silence. The younger man had applied a scientific logic to his craft, making up for his weak “heavy punch” with a lightning-fast defensive punch. In over an hour of fighting, Sullivan landed only one punch on his opponent, and the match was to mark the Boston fighter’s last time in the ring.

Corbett went on to defeat British champion Charley Mitchell in 1894, and became famous all over the world as heavyweight champion. He also became the first boxer to make his debut on the silver screen, when he was filmed at Thomas Edison’s studios, taking just six rounds to knock out Peter Courney. Corbett lost the heavyweight title in 1897 to Robert Fitzimmons.

His distinctive attire and mild-mannered personality also earned Corbett leading parts in several plays, including Cashel Byron’s Profession by George Bernard Shaw. When it came to immortalizing his life on film, the task fell to another Irish American — actor Errol Flynn. Corbett died on February 18, 1933 in New York City.

Jack Dempsey

The Manassa Mauler

Probably the most memorable fight of Jack Dempsey’s career was his last. Having lost his heavyweight title to Gene Tunney in 1926 in a decision match, Dempsey’s indomitable fighting spirit resurfaced the next year in a series of blows to Tunney’s jaw. Tunney went down, but the referee didn’t start the count until Dempsey moved to a neutral corner a few seconds later.

That few-seconds mistake cost Dempsey the title. Tunney didn’t rise until the “official” count of nine, and went on to win by decision.

The match not only marked the end of Dempsey’s career, but also the dominance of the Irish in boxing. The great fighters of Dempsey’s childhood had names like O’Brien, Dillon, Ryan, and O’Dowd. So “green” was the boxing ring that the Ancient Order of Hibernians remarked on the degrading effect it was having on the Irish image in America.

William Harrison Dempsey was born in 1895 in Manassa, Colorado, one of 11 children from a long line of Dempseys from County Kildare. He learned to fight as a way to survive after leaving home at 16 to aimlessly travel west. It was Jack “Doc” Kearns who first noticed Dempsey’s remarkable strength, and quickly arranged fights for him. Dempsey won the heavyweight title in 1919 from Jess Willard, and successfully defended it for seven years.

One sports historian sums up the “Manassa Mauler’s” greatness with this: “Dempsey may certainly rank among the great heavyweights of the past. He was not so fine a boxer as Corbett, or so wily a strategist as Fitzsimmons. He had not Jeffries’ immense strength, and certainly none of Johnson’s defensive genius. But he had more fighting spirit than was in all four of them rolled together.”

Dempsey was inducted into the Boxing Hall of Fame seven years after his death on May 31, 1983.

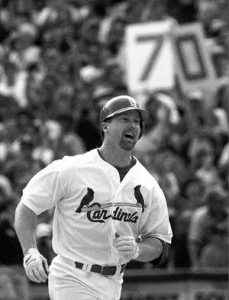

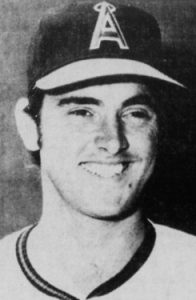

Mark McGwire

Slugger

“It still blows me away. It really does. Considering when I was a kid and all I ever wanted to do was pitch . . . then the next thing you know, they’re talking about my name along with Babe Ruth, Maris, Mantle, down the line. It’s overwhelming.”

With Chicago’s Sammy Sosa nipping at his heels all the way, the Cardinals’ Mark McGwire set an astonishing new 70-home-run record last year. It was a magical year for baseball fans who kept a close eye on proceedings as the 6-foot, 5-inch red-haired California native surpassed records previously set by Babe Ruth (60 home runs in 154 major-league games) and Roger Maris (61 homers in 161 games) and made it look somehow easy.

Born October 1, 1963, in Pomona, California to John and Ginger McGwire, the genial athlete joined the ranks of the greats with his record-making feat. McGwire started with the Oakland A’s as a pitcher and was moved to first base because of his powerful hitting skills. He was traded to the St. Louis Cardinals in 1997.

In an interview with this publication last year, McGwire said he hadn’t made much of an effort to trace his Irish ancestry, but added: “Maybe I’ll go back some day when I’m retired.”

Off the field he is admired for his passionate dedication to children’s causes. The father of an 11-year-old son, Matthew, McGwire has started a foundation which funds child abuse centers in St. Louis and Los Angeles. He has also recorded a public service announcement to publicize the cause, and plans to work on a documentary on the issue.

“You have to like Mark McGwire, ballplayer,” concluded sportswriter John Kernaghan after interviewing him last year for Irish America. “But you like the man better.”

John McEnroe

Tennis Titan

“Everybody loves success, but they hate successful people.“

Wimbledon was always so much more interesting when John McEnroe was around. From his fiery ball-bashing to his inevitable temper tantrums, the curly-headed court champion dominated the scene in a way that today’s milder players can never hope to emulate.

The statistics are awesome. The youngest player to advance to the men’s semifinals in Wimbledon history, McEnroe has a total of 77 singles titles, including seven Grand Slams, under his belt. He joined the circuit in 1978, at the age of 19, and within three short years he had reached the No. 1 spot. Defeated by Bjorn Borg in the 1980 Wimbledon finals, after a thrilling five sets, the tenacious “Mac” returned the following year to claim his first Wimbledon title in just four sets.

“Superbrat,” as he became known on (and off) the court, is also hailed as one of the greatest doubles players of all time, and at one point he ranked No. 1 for almost five consecutive years. He has 74 doubles titles, including eight Grand Slams. In 1984, McEnroe became a tennis commentator, and he was one of the professional observers at this year’s Wimbledon championships. He made no secret of the fact that he was rooting for Andre Agassi, who was defeated in the final by Pete Sampras.

Born in West Germany to John and Kay McEnroe, and raised in Queens, New York, McEnroe is descended from Irish Catholic immigrants. He was recently inducted into the Tennis Hall of Fame.

Frank Leahy

Leader of the Lads

“[We will win] and if we don’t I will take the blame.“

One of the most successful coaches in the history of college football, Frank Leahy rose from humble beginnings to put himself and his “lads” firmly on the sporting grid. His legacy lives on today at the University of Notre Dame, a testament to his hard work and burning desire to succeed.

Born in McNeal, South Dakota in 1908 of Irish parents, Frank Leahy was a serious young man who worked diligently at every task assigned to him whether at home or in school. In high school, he excelled in sports, particularly football, basketball, baseball and amateur boxing. He caught the eye of the legendary Knute Rockne who offered the young Leahy an athletic scholarship to attend the University of Notre Dame. Leahy played for Rockne at Notre Dame and then embarked on a coaching career with assistant coaching stints at Georgetown, Michigan State and Fordham before landing his first head coaching job at Boston College. After two successful seasons at Boston College, he accepted the offer to be head coach at his alma mater, the University of Notre Dame, at age 33.

During Leahy’s 11 years as the head football coach at Notre Dame (1941-’53), his record was nothing short of phenomenal. With two years out of coaching because of the war, Leahy’s teams won four undisputed National Championships — 1943, 1946, 1947, and 1949 — and a split Championship in 1953. His teams were undefeated in six of the seasons and had an undefeated string of 38 consecutive games. His overall record (including two years as head football coach at Boston College) of 107 wins, 11 defeats and 9 ties for a .864 percentage makes Leahy the number two ranked coach in all of college football, second only to Knute Rockne. During that period four of his players won the Heisman Trophy, two the Outland Trophy and twelve have been inducted into the College Hall of Fame as was he. No college football coach can match this achievement.

Leahy was known as much more than a great coach, he was known as a molder of men. He taught his players, or “lads” as he liked to call them, more than winning football, he taught them lessons of life. In recognition of their respect and gratitude for their coach, The Leahy Lads formed the Frank Leahy Memorial Fund in 1994 to raise money to honor their coach with a visible reminder of the coach and a scholarship fund in his name. The first goal was achieved in September 1997 when a ten-foot-high bronze sculpture of Coach Frank Leahy was dedicated outside the Notre Dame stadium. In addition, the Lads formed the Frank Leahy Scholarship Fund, an endowed fund administered by the University that allows deserving young students, both male and female, to further their education at the school Frank Leahy loved so much. There are currently four students being educated because of the Frank Leahy Scholarship Fund.

The legacy of Frank Leahy is more than that of a successful football coach, it is an inspirational story of an Irish American man who has influenced countless numbers of young men who played for him. And the story is ongoing. So long as the University of Notre Dame exists, Frank Leahy will continue to inspire young students and all who visit the sculpture. This is truly the mark of an influential man.

Connie Mack

Baseball Supremo

“Play ball . . .”

One of the pioneering greats of baseball, Connie Mack played a huge role in popularizing the new sport. Born Cornelius McGillicuddy in 1862 to Irish immigrants Michael McGillicuddy and Mary McKillop, Mack (“Connie Mack” was a nickname bestowed on him in childhood, and he stuck with it as he grew into adulthood) left school at age 13 and became a factory laborer. His free time was consumed with baseball, which he played on weekends.

After a number of years as a player, Mack joined the Pittsburgh Pirates of the National League, eventually becoming manager. His team played in the 1905 World Series, losing to the New York Giants, but came back in 1910 to win the league pennant and the World Series. In the four years that followed, Pittsburgh gained three league titles and two more World Series wins.

Trouble started in 1914, with the onset of World War I, and the Pittsburgh Pirates ran into financial difficulties that led Mack to make the difficult decision of letting some team members go. The move did untold harm to his reputation and the team’s performance, and it was not until 1922 that he and the Pirates recovered, with another league pennant and a fourth World Series title. Mack received the Edward Bok Philadelphia Award for his positive influence on the sport of baseball.

Elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1938, Mack saw Pittsburgh’s Shibe Park renamed Connie Mack Stadium in 1953, three years before his death. Most of today’s baseball managers follow his scientific style of keeping detailed notes on hitters and pitchers.

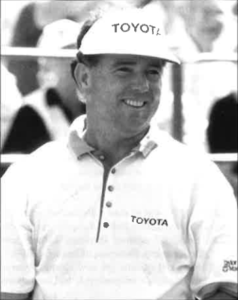

Mark O’Meara

Golfer

“Every time we go to Ireland, before we leave, we always start to plan our next trip.“

The dream of winning one of golf’s most prestigious events is enough to sustain most pros through all those fallow years. But it is rare for a golfer to grind it out for 18 years on the tour and then win two glamour tournaments in one season.

Mark O’Meara did it in 1998 at the advanced age, at least for golf, of 46. He won the Masters and slipped comfortably into the green jacket of the winner, then a few months later held firm during a four-hole playoff to capture the British Open and hug the claret jug that is traditionally awarded.

O’Meara became the oldest man to win two major titles in one year and he came awfully close to matching the legendary Ben Hogan’s three majors in a year when he came up short in the final round of the PGA Championship.

And after the shortest off-season in the history of professional sport, just 24 days, the Orlando-based veteran feels grateful for his dream season. “It was a lot of fun,” he said on the PGA Tour’s website of his remarkable year. “I knew that ’99 would come around fast and there wasn’t a whole lot of time off, but I don’t feel tired. Even at the end of the year when I traveled around the world, I felt mentally fresh.” He said he cherished his wins in the majors more because of that 18-year test of patience and his experience means, now that he’s successful, he can handle the inevitable dry spell better.

O’Meara is no stranger to Ireland. He took time out before winning the British Open to play a few practice rounds with Tiger Woods and Payne Stewart at Ballybunion Golf Club in County Kerry. O’Meara’s father, also an avid golfer, who has played the Irish greens with his famous son on more than one occasion, once said, “Every time we go to Ireland, before we leave, we always start to plan our next trip.”

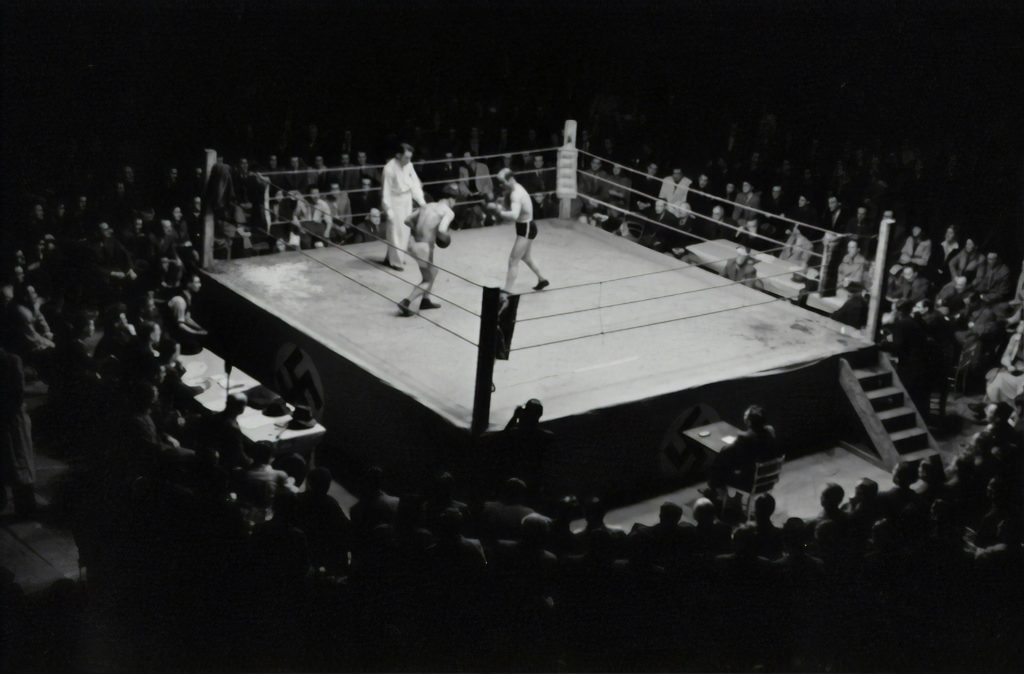

Gene Tunney

The Fighting Marine

One of the great heavyweight boxers of the century, Gene Tunney will always be remembered for the “Long Count” fight. With just one professional defeat in an 76-fight, 11-year boxing career he quickly joined the ranks of great champions.

Born James Joseph Tunney in New York City on May 25, 1898 to parents from Kiltimagh, Co. Mayo, he worked for the Ocean Steamship Company as a clerk, and began boxing at the age of 17. His father had given him his first pair of boxing gloves when he was ten years old. An early ambition to join the priesthood was abandoned, and Tunney worked for a while as a stenographer.

In 1917, Tunney joined the U.S. Marine Corps and served in France during World War I. While in Paris he won the light heavyweight championship of the American Expeditionary Force, which earned him the nickname “The Fighting Marine.”

After returning home, Tunney pursued a career in prize-fighting, and he fought against Harry Greb in the 1922 U.S. light heavyweight championship. He lost that year, but returned the next year to take the title from Greb.

By 1924, Tunney was fighting as a heavyweight, and in 1926 he challenged fellow Irish American Jack Dempsey to a match in Philadelphia. Dempsey was the favorite to win, but Tunney triumphed after ten rounds.

The two met again the next year in a rematch which gave rise to the controversial “long count,” occurring when Dempsey knocked Tunney to the floor but failed to return to his coner immediately, thus giving the fallen man a precious few extra seconds to recover. Tunney went on to defeat Dempsey in ten rounds. In 1928, Tunney successfully defended his title again against Tom Henney, after which he announced his retirement from boxing.

He went on to a very successful career as a businessman in the varied fields of banking, manufacturing, insurance and newspapers. He authored two books — A Man Must Fight and the autobiographical Arms for Living. He had four children, one of whom became a U.S. Senator. Tunney died November 7, 1978 in Greenwich, Connecticut.

John L. Sullivan

Boston Strong Boy

“My name’s John L. Sullivan, and I can lick any man in the world!“

He was known to drink almost as hard as he fought, but John L. Sullivan — “The Great John L.” — was much adored by the legions of fans who loved to see him win in the ring, which he invariably did for much of his career.

Born in Boston in 1856 to Michael Sullivan from Kerry and Roscommon immigrant Catherine Kelly, John Lawrence Sullivan was much more interested in sports than his school studies, and he immersed himself in baseball, a game he loved. As he grew bigger, however, Sullivan developed an interest in boxing, and fought his first exhibition match at the age of 22, after the fighter in the ring challenged members of the audience to a sparring bout. He won that contest, and then sensibly took a year out to further study various boxing techniques.

His return to the ring, in 1879, was marked with another victory, but it took three years of exhibition fights before Sullivan finally got his chance. On February 7, 1882, he faced off against Tipperary native Paddy Ryan, commonly regarded as the American champion of boxing. Sullivan knocked Ryan out in the ninth round and became the new champ. Ryan later said: “When Sullivan struck me, I thought a telegraph pole had been shoved against me sideways.”

At the time, boxing was still fought bare-knuckled, and Sullivan went on to fight a wide range of opponents, winning all his matches. In 1887, shortly after beating English fighter Charlie Mitchell in France, he was rapturously welcomed in Dublin City, where fans were proud to call out the Boston greeting, “Shake the hand that shook the hand of John L. Sullivan.” In 1889, Sullivan lasted an incredible 75 rounds against fighter Jake Kilrane, and the fight ended after doctors warned that Kilrane would die if he stayed in the ring.

On September 7, 1892, Sullivan entered the ring against a fellow Irish American, “Gentleman” Jim Corbett, for a gloved fight. The match went 21 rounds, but the younger Corbett emerged victorious. It was to be Sullivan’s last fight.

In later years he turned to acting, and also appeared on the vaudeville circuit. He opened bars in New York and Boston but never really managed to make a successful living as a saloon-keeper. Sullivan died on February 2, 1918, never having fully recovered from the death of his beloved second wife, Kate Harkins, the previous year.

Nolan Ryan

Pitcher Perfect

“I like being known as just a regular guy. I’m not perfect. I have my likes and dislikes, my pet peeves, and … my opinions. I’d rather have you not like me for who I am than like me for who I’m not.“

Winning all but 6 votes of the 497 cast in January of this year, Texas native Nolan Ryan swept into baseball’s Hall of Fame in the very first year he was eligible. Ryan threw his final pitch on September 22, 1993 after 27 dazzling seasons – the longest by any major league player in history. During that time he had 5,714 strikeouts and seven no-hitters, both of which are record-making tallies. He won a total of 324 games.

Born Lynn Nolan Ryan, Jr. in Refugio, Texas, on January 31, 1947, Ryan now lives in Alvin with his wife Ruth. The couple has two sons, Reid and Reese, and a daughter, Wendy. In a past interview with this magazine, he described his off-the-field devotion to ranching, describing the work as “a very big part of my year-round activities.” He owns three cattle ranches in Texas, and serves as chairman of The Express Bank, which he also owns. In 1995, he was appointed to a six-year term as a commissioner with the Texas Parks and Wildlife Commission.

In his 1992 book Miracle Man, co-written with Jerry Jenkins, Nolan remarked: “My basic philosophy of life came from my parents: Treat people the way you want to be treated, with honesty and integrity.”

Back in 1991, after interviewing Ryan for Irish America, Mary Pat Kelly concluded, “Like so many Americans of Irish descent in this country a long time, only Nolan Ryan’s name indicates a connection to Ireland…but talking about his pride in his family animated him, and if that doesn’t make him an Irish American, nothing does.”

Editor’s Note: This article was originally published in the November 1999 issue of Irish America. ⬥

Leave a Reply