Eamon de Valera

The Long Fellow

“I am in America as the official head of the [Irish] Republic, established by the will of the people in accordance with the principles of self-determination.“

Given that nobody born outside the United States can ever hope to become President of this nation, it is ironic that a humbly-born New Yorker was elected President of Ireland in 1959 and went on to serve two seven-year terms. Eamon de Valera, or `Dev,’ as he was commonly known, had a long association with Ireland and Irish causes, an association which predated his presidency by five decades.

Born October 4, 1882, at the Nursery and Child’s Hospital on Lexington Avenue in New York (a plaque commemorates the spot, now a Loews Hotel), de Valera had a difficult childhood. His mother, Kate Cull, had emigrated to New York from Co. Clare some three years earlier and worked as a domestic for a wealthy French family. The family’s Spanish music teacher, Vivian de Valera, was to father her child, but it is not known whether he died shortly after his son’s birth or simply abandoned mother and son.

Christened Edward, the youngster was put into the care of another Clare woman, and when he was three he was sent to live with relatives in Ireland. His mother later married an Englishman named Charles Wheelwright, and she continued to live in New York.

A promising student, de Valera later became a teacher. He also immersed himself in Irish nationalism, joining the Gaelic League, the Irish Volunteers, and later the Irish Republican Brotherhood. One of the leaders of the 1916 Rising, he escaped execution and changed his name to Eamon, the Irish version of Edward.

The year after the Easter Rising, de Valera was chosen as leader of the newly-formed Sinn Féin party and served as a member of Parliament. When his party boycotted the British parliament and set up their own Dáil (Parliament), de Valera became its leader. After the founding of the Irish Free State in 1922, and the Civil War which followed, he founded his own political party, Fianna Fáil.

In 1932, de Valera became leader of the Irish Free State, or Taoiseach (Prime Minister). He continued to dominate Irish politics for decades, serving as Taoiseach from 1932-’48, 1951-’54 and 1957’59. Loved and hated in equal measures, he certainly did much for the preservation of the Irish language. He is also the only politician to have served as both Taoiseach and President of Ireland.

De Valera died at the age of 92 on August 29, 1975. His granddaughter, Síle de Valera, followed in his political footsteps and serves as the current Fianna Fáil Minister for the Arts, Culture, Gaeltacht and the Islands. A grandson, Eamon O Cuiv, is another member of Fianna Fáil and the Dáil.

Patrick Ford

Patriot

“[America] is Ireland’s base of operations. Here, in this Republic . . . we are free to express the sentiments and to declare the hopes of Ireland.“

One of the great Irish American newspapermen, Patrick Ford published the Irish Worm in New York in the late 1800s and early 1900s and wrote sympathetically of the plight of American Indians and African Americans at a time when it was highly unpopular to do so. He was also a committed advocate of freedom in Ireland.

Although he could remember little of his life in his native Ireland, having moved to Boston at the age of seven, Ford devoted his life to Irish causes, specifically the issue of independence. “I might as well have been born in Boston,” he told a reporter in later years. “I brought nothing with me from Ireland…nothing tangible to make me what I am.”

There might not have been anything tangible about it, but the fact remains that through his incarnations as both a dedicated newspaperman and a diehard nationalist, Ford brought plenty with him from Ireland, and spent his adult years making sure he was in a position to give back to the country he loved so much.

Orphaned young and educated in Boston, Ford was inspired to support the Irish straggle for independence after encountering the anti-Irish sentiment that fiddled his adoptive city. During the Civil War he served with the Ninth Massachusetts Regiment.

Stints at newspapers such as The Liberator, the Boston Sunday Times and the Charleston Gazette were followed by Ford’s decision to start his own publication, the New York-based Irish World, which quickly became the most widely read Irish American newspaper of its time.

In the 1880s, Ford organized 2,500 branches of the Irish Land League, and raised $300,000 for its efforts. British Prime Minister Gladstone reportedly said at the time: “But for the work the Irish Worm is doing, and the money it is sending across the ocean, there would be no agitation in Ireland.”

In his 40s, he published two books which further illustrated his antipathy towards Britain: A Criminal History of the British Empire and The Irish Question and American Statesmen. Up until two years before his death, Ford remained editor of The Irish World. He died at his home in Brooklyn in 1913.

John Devoy

Rebel with a Cause

“The land of Ireland belongs to the people of Ireland and to them alone, and we must not be afraid to say so.”

John Devoy was only a boy, no more than nine or ten years old, when he decided he could no longer in conscience join his classmates when they sang “God Save the Queen” at school. It was to be only the first rebellious act in a long life filled with them.

Born on September 3, 1842 in County Kildare to William and Elizabeth Devoy, John Devoy moved with his family to Dublin when he was seven. In 1861, he joined the Irish Republican Brotherhood and swore an oath to the Irish Republic, promising to bear arms “to defend its integrity and independence.” He learned the soldier’s trade during a brief stint with the French Foreign Legion, spending a year in Algeria.

In 1866, during a strong clampdown on the IRB, Devoy was arrested and sentenced to 15 years penal servitude. A special deal five years later saw him released from prison on condition he leave Ireland forever. He arrived in New York on January 18, 1871, along with O’Donovan Rossa. After finding work as a reporter with the New York Herald, Devoy turned his hand to more serious business. He joined Clan na Gael and helped mastermind the rescue of Fenian prisoners from Australia on board the ship Catalpa.

During his time in New York, Devoy founded two newspapers, the Irish Nation and Gaelic American, and helped greatly with work on the United Irishmen, edited by Arthur Griffith. In 1879, Devoy and Michael Davitt worked together on the “New Departure,” which had as its goals the promotion of tenants’ rights, the achievement of self-government, the exclusion of sectarian issues from politics, and support for snuggling nationalities.

Devoy visited his native Ireland in 1924, for only the second time since his exile. Four years later, he died in Atlantic City, New Jersey, at the age of 86. He would no doubt have reveled in the obituary published by the Times of London, which referred to him as “the most bitter and persistent, as well as the most dangerous, enemy of this country which Ireland has produced since Wolfe Tone.”

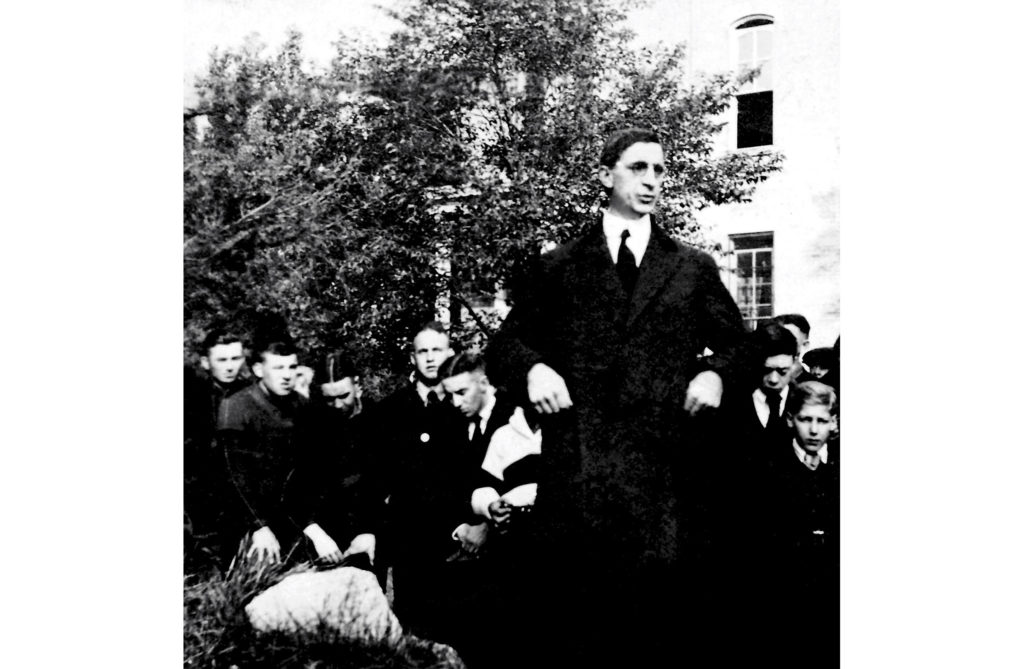

Joe McGarrity

Celtic Warrior

“… the general awakenking that was taking place in Ireland seemed to make us forget everything else for the time and only think of the fight in the prospect.”

Joe McGarrity was Eamon de Valera’s right-hand man in America, and was once described by poet Padraic Colum as “a gallowglass ready to swing a battleaxe with his long arms.” It was an apt description for the old warrior.

McGarrity was born in Carrickmore, County Tyrone, in 1874. Legend has it that as a penniless 16-year-old he walked to Dublin, boarded a cattle boat to Liverpool disguised as a drover, and sailed to America on someone else’s ticket. He settled in Philadelphia and made a fortune selling liquor and real estate.

He joined Clan-na-Gael, the Fenian movement in America, and devoted his life to the cause of Irish independence. He conferred the title “President of the Irish Republic” on Eamon de Valera when the latter landed in New York in June 1919 to seek U.S. support for the Irish Republic declared by the first Dáil in January 1919.

De Valera’s title was “President of Dáil Eireann.” Joe argued that Americans had no idea what “Dáil Eireann” meant but that “President of the Irish Republic” was analogous to the title “President of the United States” and its use by de Valera would make that clear.

Henceforth, McGarrity was de Valera’s first lieutenant in America and a fount of wisdom on all problems until the mid-1930s when the ex-President of the Irish Republic suppressed the IRA under the Offences Against the State Act and used military courts to jail them. McGarrity ended all contact with de Valera.

Almost two decades earlier McGarrity had exposed a plot against de Valera by his enemies in New York, which, if successful, would have forced his return to Dublin in disgrace and ended in his defeat because he had incurred the wrath of Judge Daniel Cohalan and the aged Fenian veteran, John Devoy, as Dáil Eireann’s spokesman in the U.S.

Devoy, writing in the Gaelic American, denounced de Valera for a published interview with a British correspondent in which the politician had said Britain should declare a “Monroe Doctrine” for Ireland, as the U.S. had done for Cuba. Devoy’s point was that the Monroe Doctrine had made Cuba a dependency of the United States. De Valera, however, seemed ignorant of Cuba’s real status.

Discussion of the issue at a large meeting in the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel turned into an indictment and trial of de Valera. McGarrity, who had letters proving this was a plot, saved the day for de Valera. “From the day I landed in America, I had the absolute cooperation of Joe McGarrity,” de Valera declared. “If I were dying tomorrow and had the power to hand over the cause of Ireland to one man, that man would be Joseph McGarrity.”

On December 9, 1920, on the eve of his return home to Ireland, de Valera did exactly that. He nominated “Joseph McGarrity of 3714 Chestnut x St., Philadelphia, as my substitute, entitled to act with all my powers in case I am incapacitated by imprisonment or death or any other cause. I anticipate to be absent from the U.S. for some time. During my absence I wish you to act for me as Trustee of Dáil Eireann in regard to such funds as are at present in the US.” McGarrity died on September 4, 1940.

Editor’s Note: This article was originally published in the November 1999 issue of Irish America. ⬥

Leave a Reply