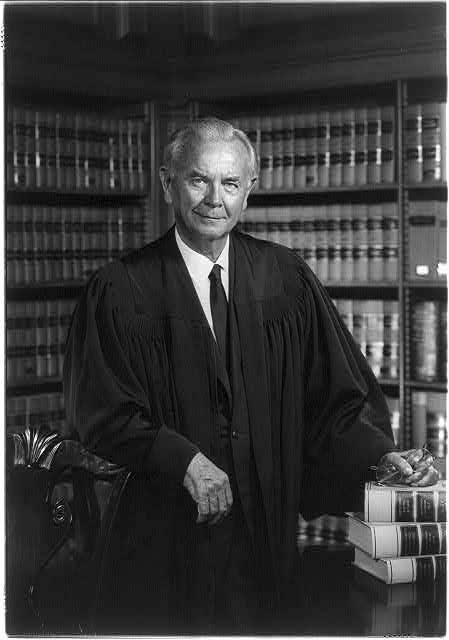

William J. Brennan, Jr.

Lion of the Court

“The law is not an end in itself, nor does it provide ends. It is preeminently a means to serve what we think is right. “

Considered one of the most influential shapers of public policy in the nation, the late Justice William Joseph Brennan, Jr., was best known for his support of civil rights, and particularly freedom of speech. He was a figure of immense importance in modern law, and it was his guiding hand that spurred the revolution in constitutional law in the 1960s and ’70s.

In a rare interview with Irish America magazine in 1990, Brennan discussed his background. Born April 25, 1906 in Newark, New Jersey to Roscommon immigrants William Joseph Brennan and Agnes McDermott, Brennan was the second of eight children. His parents were reluctant to talk of their lives in Ireland, leading Brennan to conclude that “their memories were of hardships,” but they brought up their family with a strong sense of Irishness.

Brennan and his siblings were raised to be aware of the Friendly Sons of Saint Patrick and the Ancient Order of Hibernians. The senior Brennan also subscribed to the Irish World and other such publications, and St. Patrick’s Day was a big occasion for celebration in the household. “Everything I am, I am because of my father,” Brennan once said.

Brennan graduated from Harvard Law School in 1931 and started his career with the New Jersey firm of Pitney, Hardin &Skinner. He was named a judge of the State Supreme Court in 1949, and three years later was elevated to the New Jersey Supreme Court. In 1956, President Dwight D. Eisenhower appointed Brennan to the Supreme Court, and he became its youngest member. During his 34 years on the Supreme Court bench, Brennan published over 1,250 opinions, including several landmark decisions on such issues as the rights of racial minorities and women and the protection of freedom of expression.

His Catholicism proved no barrier to Brennan’s fervent belief in the strict separation of church and state. He was married to Marjorie Leonard and the couple had three children. After Marjorie died in 1982, Brennan married Mary Fowler, who had worked as his secretary for over 25 years. He died on July 24, 1997 in Arlington, Virginia at the age of 91.

Sandra Day O’Connor

Defender of Justice

“I don’t know that there are any short cuts to doing a good job.”

On September 25, 1981 Sandra Day O’Connor took the oath of office as a Justice of the United States Supreme Court, becoming the first woman ever to serve on the court. Given the curious chemistry of the current court on which she sits, she has garnered enormous power, as hers has proven to be the key swing vote on a wide range of contentious issues, from affirmative action to abortion to the death penalty. In 1993 the American Bar Association Journal hailed her as “arguably the most influential woman official in the United States.”

O’Connor is the descendant of famine immigrants named O’Dea, but her grandfather changed the name to “Day.” Sandra Day O’Connor was born in 1930 in El Paso, Texas on an isolated ranch. Located too far from any schools, Sandra’s mother taught her to read, and at the age of five, Sandra was sent away to attend school. She returned to the ranch at age 13, and made a 22-mile trip each day to attend high school. After finishing high school, she enrolled at Stanford University, receiving her law degree in 1952. That same year she married her classmate John Jay O’Connor III.

O’Connor applied for jobs at several law firms, but they were reluctant to hire a woman. O’Connor turned instead to public service, working as deputy county attorney in San Mateo, California.

The O’Connors moved to Arizona in 1957, and there Sandra opened her own law firm in order to have time to spend with her three sons Scott, Brian and Jay. In 1969, she was elected as a Republican to the Arizona State Senate. Three years later she was elected Senate Majority Leader, becoming the first woman to hold that office in any state senate in the country. That same year, she also served as Chairman of the State, County and Municipal Affairs Committee. She also served on the Legislative Council, the Probate Code Commission and the Arizona Advisory Council in Intergovernmental Relations.

In 1974, O’Connor was elected county judge, and five years later, the governor of Arizona appointed her to the state court of appeals. In July of 1981, she was nominated by President Reagan as Associate Justice of the United States Supreme Court, taking the oath two months later. From making history to interpreting the law of the land to raising three boys, O’Connor has done it all and remains a shining example for women in this country.

When asked during her confirmation hearings how she wanted to be remembered, she replied with the unflappability that has characterized her career, “Ah, the tombstone question. I hope it says, `Here lies a good judge.'”

Vincent Hallinan

The Great Defender

“We’re not fallen angels. We’re risen apes.“

He’s probably the only lawyer who appeared before the courts and defied the defense to prove the existence of heaven. As well known in his native San Francisco as Clarence Darrow was in Chicago, Vincent Hallinan helmed a number of high-profile cases, often ending up behind bars himself for his troubles. A 300-page biography of Hallinan by James P. Walsh is rifled San Francisco’s Hallinan: Toughest Lawyer in Town, which gives some idea as to his reputation. He was almost as well known for his strident politics, and once ran for President.

Born to Irish immigrants on December 16, 1896, Hallinan learned his firt legal lesson at his father’s knee, and remembers it as “the incident that determined my career.” Hallinan senior, facing eviction with his wife and seven children from their Western Addition apartment, enlisted the help of attorney Charles Heggerty, who first counseled his client of the necessity to keep the process servers at bay for as long as possible and then had the eviction case thrown out of court on the grounds that the notice to vacate was “fatally defective.”

Heggerty cited the case of Spivolo v. Mahoney as grounds for his argument. Hallinan remembers his father marveling at the judge’s ignorance of this landmark case, but it was only years later that the son, then a learned attorney, “saw the thousands of books and recognized that there were numberless decisions [and] realized the wonder would have been if [the Judge] had heard of Spivolo v. Mahoney.”

One of Hallinan’s most notorious cases involved his spirited defense of Pacific Heights society matron Irene Mansfeldt, charged with killing her husband’s mistress. Mansfeldt confessed to police, but Hallinan refused to let her sign it, and advised her to say nothing further. In an explosive trial, during which he completely destroyed the prosecution’s medical expert, Hallinan did a splendid job of convincing the jury that Mansfeldt had killed the other woman during a haze brought on by drugs her husband, a doctor, had prescribed for her. He saved his client from the gas chamber and she got off with a comparatively light custodial sentence of 25 months. In a 1989 interview with this publication, Hallinan told writer Frank McCourt, “It was far and away the best victory I’ve ever won in court.”

Asked where he picked up the dramatic flair he employed to such good use in the courtroom, Hallinan said: “A lot of things I’ve said I’ve extracted from books. When I was a little fellow, only seven, my father used to give me money to memorize Irish poems and recite them. I’d give the money to my mother, of course. It helped me build a tremendous memory.”

Married to Vivian, Hallinan was a devoted father to the couple’s six sons, many of whom are carrying on the family legal tradition in San Francisco today, including Terence, the city’s District Attorney. His wife wrote a book in the 1950s entitled My Wild Irish Rogues, which focused on raising her staunchly leftist political sons in the midst of political turmoil. Vincent Hallinan, a lifelong socialist who described himself as a “mating atheist,” died in 1995.

Editor’s Note: This article was originally published in the November 1999 issue of Irish America. ⬥

Leave a Reply