Mary Harris “Mother” Jones

Miners’ Angel

“Pray for the dead and fight like hell for the living.”

Mother Jones was one of America’s most effective union organizers. At a time when few women were activists, she was a fearless crusader for the rights of American workers and became the champion of child laborers. But most of all, she was the “miner’s angel” often risking arrest and her own safety in her support of the miners’ struggle for safer working conditions and better pay. It was the miners who dubbed her “Mother” Jones.

A tiny woman in a black dress with a lace collar, steel-rimmed spectacles and snowy hair pulled back in a bun, Jones could have been mistaken for someone’s genteel, soft-spoken grandmother, until she opened her mouth. Her speeches appealed to laborers’ sense of justice and self-respect and rallied them to action.

She herself was no stranger to sorrow and oppression. Born Mary Harris in Cork, Ireland in 1837 to a poor family, she knew what it was like to be treated as a second-class citizen. Her family had a history of activism: her grandfather was hanged as a traitor to the crown, and her father was forced to leave Ireland for defying British rule. Richard Harris and his family settled in Canada where he found work on the Canadian railroads. After finishing her secondary education, Mary trained to become a teacher and also learned dressmaking.

Alternating between dressmaking and teaching, Mary moved around a great deal before settling in Memphis, Tennessee, where she met and married George Jones, a union iron molder, in 1861. They had four children.

In 1867, a yellow fever epidemic swept through Memphis’ Irish section, killing George and their four children. Mary Jones returned to Chicago only to suffer more loss. In 1871, the Chicago Fire destroyed her home and her dressmaking business. Her father died in Toronto only two months later.

Working for the affluent as a dressmaker while living among the poor, Jones grew enraged at the disparities between the classes. She began to attend political and labor protest meetings, ultimately launching her own campaign for workers’ rights, first for Irish railroad workers and miners, then for all laborers. Over the next 25 years she criss-crossed the country, fueling workers’ hopes and inciting their strikes. In 1901, she was a commissioned organizer in West Virginia for the United Mine Workers. She walked miles of railroad, scaled cliffs and waded across streams to attend secret meetings. She was arrested in 1902 for her efforts and was declared “the most dangerous woman in America.”

The following year, she led a Children’s March from New Kensington, Pennsylvania to Oyster Bay, Long Island, the summer home of President Theodore Roosevelt. She wanted to show the President what happened to victims of child labor. Roosevelt refused to meet them.

In 1913, she returned to West Virginia to participate in the Paint Creek strike. She was arrested, court-martialed and sentenced to house arrest for three months. She also testified at several Congressional hearings on behalf of miners, Mexican political prisoners and industrial workers. Her last major strikes were among the steel workers in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania in 1919 and the coal miners of West Virginia, 1921.

In 1930, only months before her death, she remained as outspoken as ever, making her debut on newsreel cameras protesting the Prohibition Act. She died on November 30 and is buried in the Union Miners Cemetery in Mount Olive, Illinois.

Teddy Gleason

The Great Negotiator

“God be with the days when if you didn’t vote Democrat you weren’t allowed to go to church on Sundays.”

For almost a quarter of a century, spearheading a period of immense growth and change, Teddy Gleason headed up the International Longshoremen’s Association. In his book Dreamers of Dreams, Donal O’Donovan wrote: “Whatever the marks of a shrewd and talented negotiator, Teddy Gleason has them.” After Gleason’s death in 1992, ILA president John Bowers said: “We have lost a great leader and a great man. I’ve noted before that Teddy Gleason will go down in history as the president who was able to get the most for his members. His memory will long endure.”

Born November 8, 1900 in New York City to Thomas Gleason and Mary Quinn, immigrants from Nenagh, Co. Tipperary and Omagh, Co. Tyrone respectively, Thomas W. Gleason was quickly nicknamed Teddy to distinguish him from his father and grandfather.

By age 15 he was working alongside his father on the West Side piers in Manhattan, the start of a career that was to span 77 years. Gleason worked various jobs on the docks, all the while further cementing his close ties to the ILA. His union activity saw him cut off from his job during the Great Depression, and he was forced to take on two jobs to support his wife and young family.

With the arrival of President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s “New Deal” and the increasing respect for unions, Gleason was able to pick up his career as a longshoreman and labor leader. He rose steadily in union ranks and became president of the ILA in 1963. The International Transport Workers’ Federation later elected him as vice president.

Gleason’s achievements in the ILA include securing a guaranteed annual income for workers hurt by increasing automation. He was also vice president on the executive council of the AFL-CIO and his expertise was often called on around the world to help out in labor disputes. His investigation into the movement of war-time cargo in Vietnam earned him a Medal of Merit in 1967 from the U.S. Veterans of Foreign Wars. He received countless other awards from such bodies as the United Seamen’s Service, the Catholic Youth Organization and The Carmelite Sisters for the Aged and Infirm. A true Irishman, however, he was most proud of being chosen as Grand Marshal of the New York St. Patrick’s Day Parade in 1984. Gleason said at the time: “It took me 80 years to get from 12th Avenue to 5th Avenue.”

Gleason was married to Emma Martin, and the couple had three sons, Thomas, Jr., John and Robert. He died on December 24, 1992 at the age of 92.

Elizabeth Gurley Flynn

Powerhouse

“The awareness of being Irish came to us as small children, through plaintive song and heroic story.“

Born to Galway native, Annie Gurley, and Tom Flynn whose roots lay in Mayo, Elizabeth Gurley Flynn was the oldest of four children. Raised on a strict diet of her father’s socialist and Marxist principles, it’s hardly surprising that she turned out to be both an active labor organizer and later a Communist official.

Talking about her ancestors, Gurley Flynn said all of her great-grandfathers had been United Irishmen. Her great-grandfather Flynn was deeply involved with the “Races of Castlebar,” and led General Humbert’s French troops from Ballina to Castlebar. His son, one of 18 children, was Gurley Flynn’s grandfather. He left his native Ireland during the Famine era for Maine, from where he later took part in the Fenian invasion of Canada.

Gurley Flynn was born in Concord, New Hampshire on August 7, 1890, and later moved with her family to the South Bronx. A bright student, she showed promise as a public speaker, and on leaving school turned to socialism and labor agitation. One magazine editor dubbed her “an East Side Joan of Arc.”

A stalwart of the Industrial Workers of the World, Gurley Flynn traveled from Montana to Washington to Chicago, speaking on behalf of workers everywhere and earning herself a spell behind bars in Spokane for her troubles. She was behind two huge demonstrations, one in Massachusetts in 1912, the other in New Jersey the following year. Her first marriage and a later common-law relationship failed. Gurley Flynn had two children, one of whom died shortly after birth.

It was in the last three decades of her life that Gurley Flynn took up her second cause, that of Communism. Elected to the party’s national committee in 1938, she wrote a regular column for the Daily Worker. A second prison sentence was to follow in the 1950s when Gurley Flynn was convicted under the Smith Act which made it illegal to advocate forceful overthrow of the government. She served over two years at the Federal Penitentiary for Women in Alderson, Virginia. Never one to waste time, she used the jail term to write her autobiography, a record of her fast 36 years. A memoir of her time in prison, The Alderson Story, was also published after her release.

In 1961, Gurley Flynn became the first woman chairperson of the American Communist party. A planned second volume of her autobiography never came to fruition, due to her untimely death in Moscow on September 4, 1964. In a final fitting tribute, the woman who embraced Communism with all her heart was accorded a state funeral in Red Square.

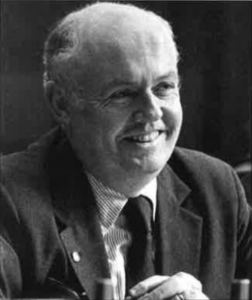

John Sweeney

Labor Leader

“America needs a raise.“

John Sweeney, president of the AFL-CIO, America’s largest labor union, has long been active in Irish affairs, and is a member of several Irish organizations. In 1995, he accompanied President Clinton on his first visit to Ireland.

Sweeney’s election as president of the American Federation of Labor-Congress of Industrial Organizations (AFL-CIO) in 1995 ushered in a new era in the labor movement. On the day of his electoral win, he led an impromptu march up Manhattan’s Fashion Avenue protesting wages and work conditions in the garment industry. Within weeks, he had established a multi-million-dollar fund to finance television and radio commercials, town rallies and telephone campaigns to hammer away at the evils of wage discrimination, job insecurity and union-busting corporations.

Born May 5, 1934 in New York’s Bronx to Irish immigrants from Leitrim, Sweeney studied economics at Iona College, and took a job at IBM after graduating. He had worked at a union job to pay his way through school and soon left IBM to take a lower-paying job with the International Ladies Garment Workers Union, a move that would set the course for his life’s work.

As president of the Service Employees International Union (SEIU) from 1980 until taking his current position, Sweeney doubled union membership and recorded countless other successes. Since his election to the helm of the AFL-CIO, he created new management posts to create leadership positions for women and minorities, all part of his goal to abolish the long-held concept of the labor movement as the domain of white males. In 1996, he wrote a book titled America Needs a Raise: Fighting for Economic Security and Social Justice. He also co-authored Solutions for the New Work Force in 1989 He and his wife, Maureen Power, have a son John and daughter Patricia.

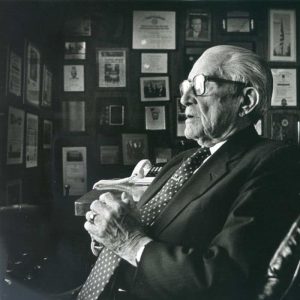

George Meany

Labor of Love

“The yearning for freedom – the insistence on human dignity – are forever enshrined as part of the Irish character. Similarly, they are the wellspring of the American trade union movement.“

Bronx native George Meany followed his father into the plumbing trade, but he saw the work only as a means to an end. His real ambition was to become involved in the labor movement, a goal he achieved with spectacular results. By the time he died, at age 85 and only weeks after he retired, Meany had held the top positions of both the American Federation of Labor (AFL) and its eventual incarnation on merging with the Congress of Industrial Organizations, the AFL-CIO. His name is synonymous with the labor movement in the U.S., and especially in his beloved New York City.

Born August 16, 1894, Meany was one of ten children, and the grandson of Irish immigrants from Counties Longford and Westmeath. His father, Michael Meany, was president of Local Two of the plumbers’ union but was adamantly opposed to having his sons follow in his footsteps. His antipathy was lost on George who became an apprentice in his teens, and soon followed on to membership of Local Two. After his father died, and his older brother enlisted in the army, Meany became the family breadwinner, a fact which delayed his wedding to Eugenie McMahon by a couple of years.

By 1952, Meany was president of the AFL, and subsequently he led the AFL-CIO. He was widely admired as a plain-speaking, scrupulously honest man, with a remarkable memory and a tough, forceful personality. He is also remembered for his tireless rooting out of corruption.

The years which preceded his election as president of the AFL involved lobbying for the New York State Federation of Labor, of which he served as president for a term in 1934. In his position as president of the AFL-CIO he was accustomed to dealing with the U.S. presidents of the time, including Eisenhower, Kennedy, Johnson and Carter. He retired in November of 1979, and died less than two months later.

Mike Quill

Himself

It was to become one of the most powerful unions in America but when the Transport Workers Union (TWU) was established in New York City in 1934 its prospects looked bleak. Conditions were terrible for the workers, who often had to work a seven-day week in dreadful conditions. Few gave it any hope of succeeding.

But the bosses reckoned with the willpower of its nucleus of founders who comprised a core group of eight or nine IRA veterans from the Irish Civil War including 29-year-old Kerry native Michael Joseph Quill. The following year, Quill was elected president of the new union.

Quill and his family in Ireland were well known in their local village for their staunch support of republicanism, and tales of young Mike’s daring exploits in foiling the Black and Tans were legendary. Several members of the family joined anti-treaty forces in the Irish civil war, and were forced to leave their native land when the war ended.

Born September 18, 1905, Quill left for America when he was just 19. He worked at various odd jobs — doorman, elevator operator, sandhog — before gaining employment with the New York subway system as a ticket clerk. Although the transport body was deeply resistant to organized labor, Quill and his fellow Irishmen persisted and succeeded in forming the TWU.

On the occasion of the 25th anniversary of the TWU, Quill remarked that he considered its greatest successes to be “the restoration of the rights of citizenship and dignity to the individual worker…I mean freedom from fear, freedom from want, freedom to speak one’ s mind.” Throughout his long association with the TWU, and organized labor in general, Quill remained an active and outspoken advocate of workers’ rights. His work helped secure better working hours and conditions for the union’s laborers. He also served as a member of the New York City Council at various times during his life.

In 1959, Quill’s wife of 22 years, Mary Theresa “Mollie” O’Neill, died of cancer. He married Shirley Uzin in 1961 and almost 20 years after his death her biography of him, Mike Quill: Himself, was released.

In 1965, Quill led a massive strike against New York’s bus and subway lines. His efforts brought the city to a standstill for 12 days and resulted in him being sent to prison. While behind bars, he suffered a heart attack, not his first, and he died less than a year later. Friends and admirers from Monsignor Charles Owen Rice to the Reverend Martin Luther King, Jr., lined up to pay tribute to his memory.

King described him as a pioneer of the modern trade movement and a pioneer in race relations. Said King: “He was a fighter for decent things all his life — Irish independence, labor organization and racial equality…When the totality of a man’s life is consumed with enriching the lives of others, this is a man the ages will remember — this is a man who has passed on but who has not died.”

Editor’s Note: This article was originally published in the November 1999 issue of Irish America. ⬥

Leave a Reply