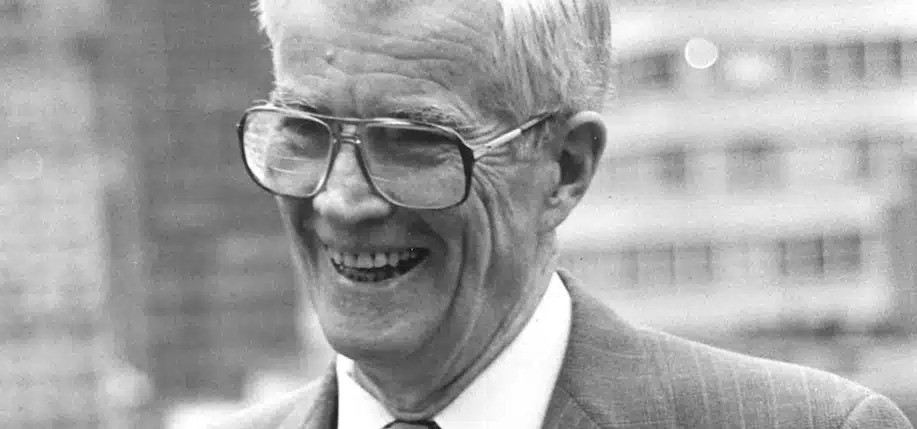

Eoin McKiernan

Champion of Education

“We can give no greater evidence of our love for Ireland than to join in the race to further the achievement of Irish children.”

Eoin McKiernan is widely acknowledged as one of the foremost authorities in the U.S. on Irish affairs, and includes on his resumé such job descriptions as author, lecturer, script writer, TV presenter, columnist and consultant. But Dr. McKiernan’s best-known contribution to Irish America is perhaps the Irish American Cultural Institute he founded in St. Paul, Minnesota with his late wife Jeanette. His current pet project is Irish Educational Services, a program that enables Irish Americans to support children in education in Ireland.

Born in Manhattan, to Irish parents from Counties Clare and Cavan McKiernan has had a life-long immersion in all things to do with Ireland and education. Since the establishment of the Irish American Cultural Institute in 1964, the organization has been responsible for countless services, including the donation of hundreds of thousands of dollars to the arts in Ireland and the setting up of the Irish Way Program, which gives American high school students the opportunity every year to study and travel in Ireland.

McKiernan’s honors from Ireland include an honorary doctorate from the National University of Ireland and the UDT Endeavor Award for Tourism. He is also the only American ever to have been made an Honorary Life

Member of the Royal Dublin Society (RDS). He has also been honored by organizations such as the Wild Geese, the AOH and the Eire Society.

On this side of the Atlantic, he holds honorary doctorates from three American universities, all in addition to his earned doctorate in English literature from Pennsylvania State University. McKiernan has nine children. A regular contributor to Irish America magazine, he now lives in Wisconsin.

Annie Sullivan

The Miracle Worker

“Children require guidance and sympathy far more than instruction.“

The dynamic partnership of Annie Sullivan and Helen Keller is one that has inspired many books, movies and even a stage play.

When Helen Keller was born in Tuscumbia, Alabama, she was quite precocious, speaking her first word at only six months and taking her first steps at age one. Her early promise was cut down when at the age of 19 months she was stricken with what is now believed to be encephalitis. She pulled through, but her parents were horrified to learn that she was left blind and deaf.

Without any proper education, young Helen ran wild, and she was seven years old before someone was found to help her. That someone was 21-year-old Annie Sullivan, the daughter of Irish immigrants from Co. Limerick. Herself poorly-sighted, Sullivan quickly proved to be an able teacher for Helen. In the early years of their work, she was both eyes and ears for Keller.

Before teaching Keller how to communicate, Sullivan first had to teach her young charge some simple discipline. They worked tirelessly together, and Keller finally, haltingly learned how to communicate again.

Sullivan taught her pupil by spelling words into Keller’s hand. The two developed a language that grew very extensive and Keller learned to read Braille. When she was ten, Keller also learned to speak clearly enough to be understood.

At the age of 19, with Sullivan’s help, Keller took the entrance exam for Radcliffe College. The older woman sat beside her, spelling the questions into her hand. Keller graduated with honors from Radcliffe in 1904.

The two worked and traveled together for fifty years, during which time Sullivan married John Macy. Sullivan died in 1936, three decades before her young pupil. The highly regarded play The Miracle Worker tells her story. She is also portrayed in a book written by Keller, entitled Teacher: Anne Sullivan Macy (1955).

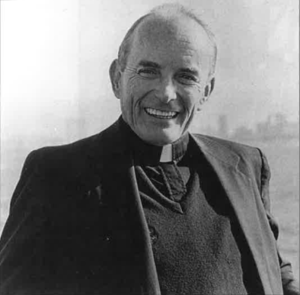

Andrew Greeley

Man of Many Collars

“The Irish are the most likely of all American ethnic groups to be in constant communication with their sister and their mother. And somewhat less so, but still ahead of everybody else, with their brothers and their father.“

Sociologist, priest, historian, best-selling author, there’s no easy way to pigeonhole Chicago native Andrew Greeley, and that’s just the way he likes it. “If you want to know what’s happened to me, read the memoirs,” he said in an interview earlier this year. “But if you want to know me, read my novels.”

The fact remains that he has done some of the most extensive research and analysis into the ethnic makeup of this country, and particularly into the history and role of the Irish in America. His book about the American Irish, That Most Distressful Nation: The Taming of the American Irish, is a ground-breaking work.

Born February 5, 1928 on Chicago’s West Side, Greeley is the grandson of Co. Mayo immigrants. In a 1995 interview with this publication he remarked that his sister traced his Irish consciousness back to his days at the University of Chicago, when he began to define himself as Irish in reaction to fellow sociology students who failed to see the importance of ethnic groups.

A Catholic priest since 1954, Greeley has been writing novels for over 20 years, with sales reaching 20 million plus. Many with Irish characters and themes, his books have entertained millions of readers for years. “I have to feel inside the skin of my characters,” he told Irish America magazine in 1986, “that’s why they are all Irish.”

But it is his tireless work as a sociologist which really earns Greeley a place in the top Irish Americans of the Century. His research has focused on such topics as contemporary issues facing the Catholic Church — including celibacy and female priests — and the decline of Irish Americans as an ethnic group.

Through his work as a research associate with the National Opinion Research Center (NORC) Greeley found in the late ’70s that “in terms of education, occupation, and income, Irish Catholics are notably above the national average for other whites” and were more likely “to attend graduate school and choose academic careers” than were white Protestants.

Greeley is professor of social sciences at the University of Chicago, his alma mater, and at the University of Arizona. In 1986 he established a $1 million Catholic Inner-City School Fund, providing scholarships and financial support to schools in the Chicago Archdiocese. Two years earlier, he contributed a $1 million endowment to establish a chair in Roman Catholic Studies at the University of Chicago.

His numerous awards and honors include the 1993 U.S. Catholic Award for furthering the cause of women in

Eileen Collins

Rocket Woman

“I didn’t get here alone. There are so many women throughout the century that have gone before me and taken to the skies … I wouldn’t be here without them today. “

On July 22, 1999, two days after the thirtieth anniversary of the first moonwalk, U.S.A.F. Col. Eileen Collins became the first woman to command a space shuttle. When she and her crew flew into space on Columbia mission STS-93 to launch the Chandra X-ray Observatory, the most advanced X-ray telescope ever produced, she, in the words of Hillary Clinton, took “one big step for women and one giant leap for humanity.”

The second of the four children of Rose Marie and James Collins, whose ancestors are from County Cork, Eileen was born in Elmira, New York in 1956. She fell in love with flying while watching planes taking off and landing at a local airport. As a teenager she held various odd jobs to pay for her flying lessons, which she took while studying at Corning Community College. She received an ROTC scholarship to Syracuse University, earning a BA in mathematics and economics in 1978. She went on to earn an MS in operations research from Stanford University in 1986 and an MS in space systems management from Webster University in 1989.

Through ROTC, Collins joined the Air Force in 1976, the first year that women pilots were accepted. After completing training as a test pilot in 1990, she was accepted for an astronaut class and became an astronaut in July 1991. In 1995, she made history as the first woman to pilot a space shuttle when NASA chose her to pilot the first U.S.-Russia Shuttle/Mir rendezvous. For this historic flight, Collins took along a scarf worn by Amelia Earhart and keepsakes from 13 female astronauts who never made it into space. “Women helped pioneer aviation,” Collins told a news briefing, pointing out that since the 1930s, “women were not given the same opportunities as men.”

Collins is married to Patrick Youngs, a Delta Airlines pilot, and they have one daughter, Bridget Marie. Her hobbies include running, hiking, camping, reading, photography and astronomy. She and her husband both play golf and they traveled to Ireland in 1993 to participate in the Irish Open.

Well aware of the important place she takes in history and of her status as role model for young women, she is a frequent visitor to high schools, encouraging girls to pursue the study of math and science. At St. Charles School in Orlando, Florida, where her niece and nephews are students, she helped start a Young Astronauts Club. An active member of the Catholic church, her faith has obviously played an integral role in her life. As she told one newspaper, “I believe God gives us hopes and dreams, the desire to do certain things with our lives and the ability to set goals.”

General Michael Collins

Rocket Man

“Man has always gone where he has been able to go, it is a basic satisfaction of his inquisitive nature, and I think we all lose a little bit if we choose to turn our backs on further exploration.“

As the 17th American in space, Michael Collins was the first astronaut to walk out twice during a single mission. He began his six-year career as an astronaut in 1964, and just two years later was commander of the Gemini 10 mission.

In January 1969, Collins was named Command Module pilot on Apollo 11, the first mission to land astronauts on the moon. As the pilot in command, he circumnavigated the moon’s surface on July 22, 1969, while Astronauts Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin took those first historic steps.

Born in Rome, Italy in 1930, Collins graduated from the U.S. Military Academy in 1952. Shortly after the Apollo 11 mission, he resigned his commission in the Air Force to take the position of Assistant Secretary of State for Public Affairs. In this position he was responsible for liaising between the State Department and the American public, with a particular emphasis on communicating with the youth population.

Collins will perhaps be best remembered, however, for his involvement in the construction and early operation of the National Air and Space Museum in Washington, D.C. In his seven years as the director of the Museum he was able to combine two of his lasting passions: his love of space and desire for greater education of this country’s youth. In 1978, Collins was named Under Secretary for the Smithsonian Institution. When he left that position in 1980, his commendation stated that “…the Smithsonian and the Nation are forever indebted to him for his service.”

Collins authored several books on space including 1974’s Carrying the Fire (with a foreword by Charles Lindbergh), which remains a classic today. Among his honors and citations are the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the Collier Trophy, the Harmon Trophy, the Thomas D. White Trophy and the Goddard Trophy. The Air Force awarded him the Distinguished Service Medal with Oak Leaf Cluster and the Distinguished Flying Cross. NASA awarded him its Distinguished Service Medal and Exceptional Service Medal.

Kathryn Sullivan

Space Walker

Dr. Kathryn D. Sullivan became the first American woman to perform a space walk, also know as extravehicular activity (EVA). She did this on the STS-41G Space Shuttle Challenger mission in October 1984. Her space walk, the purpose of which was to demonstrate the feasibility of satellite refueling, lasted three and a half hours.

The shuttle crew (Sally Ride was also on this Challenger mission, the first flight to include two women) also successfully deployed the Earth Radiation Budget Satellite (ERBS).

In April 1990, Dr. Sullivan flew on the STS-31 Space Shuttle Discovery mission. The purpose of this mission was the deployment of the Hubble Space Telescope (HST). The Hubble turned out to be nearsighted but was given a corrective lens on a later shuttle mission.

Dr. Sullivan also flew on the STS-45 Space Shuttle Atlantis mission in March 1992. This mission carried the first Atmospheric Laboratory for Applications and Science (ATLAS-1) into space. The laboratory was carried in the shuttle cargo bay.

Born on October 3, 1951, in New Jersey, Sullivan earned a Ph.D. in Geology at Dalhousie University in Nova Scotia, Canada, in 1978. Her research included oceanography expeditions. She joined the U.S. Navy and became a Naval Astronaut in 1978. In 1992, she assumed the post of chief scientist, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, having been nominated by both the Bush and Clinton administrations. She remained at NOAA through 1996, when she took up her current position as president and chief executive officer of COSI (Center of Science and Industry).

Editor’s Note: This article was originally published in the November 1999 issue of Irish America. ⬥

Leave a Reply