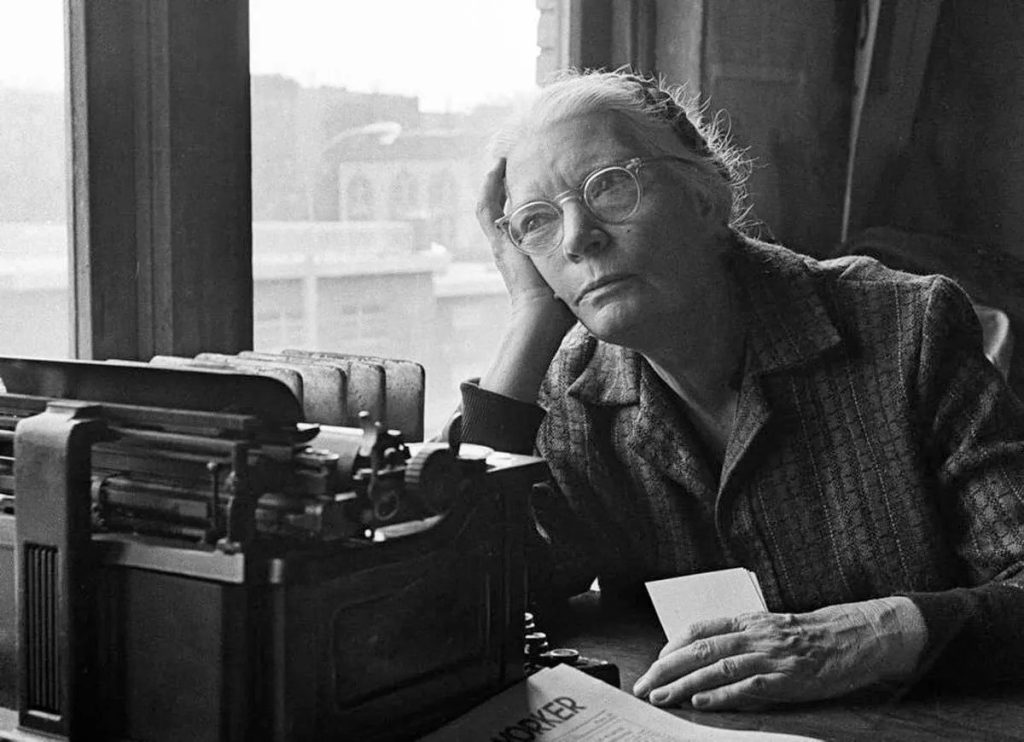

Dorothy Day

Heroine

“Don’t call me a saint. I don’t want to be dismissed so easily.”

From time to time there comes an individual whose life exposes the limitations of the written word. Dorothy Day was such a person. Her strength, singularity and ability to nudge humankind a little further up the ladder of emotional and spiritual evolution goes beyond language.

As a journalist, peace activist and founder of the Catholic Worker movement, Day’s combination of radical politics and commitment to social justice broke new ground for the American Catholic Church. While her unyielding pacifism provoked criticism during her lifetime, she has now come to be considered heroic, even holy, for her steadfast commitment to nonviolence, so much so that there is a movement to have her canonized.

Day was born in Brooklyn, New York on November 8, 1897 but spent most of her childhood in Chicago. Her father, John Day, was a newspaperman and when Dorothy was about eight years old, he went through a period of unemployment. The family was forced to move into a tenement flat over a tavern in Chicago’s South Side. Day was so ashamed of her home that on leaving school in the evenings she would enter a fancier, more impressive building so that her classmates would not know where she really lived. Her father eventually found work again and the family moved to a large, comfortable house on the North Side, but Dorothy’s memories of the grinding shame of poverty would never leave her.

Day, of Presbyterian Irish stock, became intrigued by Catholicism as a child. A formative moment came when she went to the house of a Catholic friend and found her friend’s mother, Mrs. Barrett, on her knees in prayer. Without dismay or embarrassment, Mrs. Barrett told Dorothy where her friend was and returned to her prayer. In her autobiography, The Long Loneliness, Day recalled, “I felt a burst of love toward Mrs. Barrett that I have never forgotten, a feeling of gratitude and happiness that warmed my heart.” This memory fueled Day’s own spiritual search and played a large role in her later conversion to Catholicism.

At the same time, books like Les Miserables, Bleak House, Little Dorritt and Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle were increasing her awareness of social injustice and the suffering of the poor. Prompted by her reading, Day began to explore the poorer neighborhoods of Chicago, and discovered in poverty a wealth that went beyond money. She was only 15 years old with a social awareness that went beyond her years.

An excellent student, Day won a scholarship to the University of Illinois at Urbana and enrolled at the age of 16. Refusing her family’s financial assistance, she supported herself through a variety of jobs, washing, ironing and caring for children. When she was 18, she left school and moved to New York to work as a journalist for various socialist and left-wing publications.

It was in New York that Day’s social activism truly began. In 1917, she was one of 40 women arrested in front of the White House for protesting for women’s suffrage. It was the first of many visits to the interior of a jail cell.

Meanwhile, her fascination with the spiritual discipline of the Catholic Church continued to grow. The turning point occurred in 1926. She was living on Staten Island with her common-law husband, Forster Batterham, when she found out she was pregnant. She had undergone an abortion several years previously and it proved to be the greatest regret of her life. She believed that the damage her womb sustained left her incapable of carrying another child. To Day, this second pregnancy was nothing short of a miracle and she could think of no better way to express her gratitude to God than to raise her child a Catholic.

When Tamar Theresa Day was born, Day went against the wishes of her common-law husband and had the baby baptized. “I did not want my child to flounder as I had often floundered. I wanted to believe, and I wanted my child to believe, and if belonging to a Church would give her so inestimable a grace as faith in God…then the thing to do was to have her baptized a Catholic.”

The baby’s baptism ended Day’s relationship with Batterham. While she still loved him, her now unshakable faith in God could no longer coexist with his complete lack of faith. On December 28, 1927, Day herself was baptized a Catholic.

In the years that followed, Day tried to find a way to combine her Catholic faith with her radical social values. Her chance came in the winter of 1932 when she met Peter Maurin, a French immigrant strongly influenced by the teachings of St. Francis of Assisi. Maurin encouraged Day to start a paper that would publicize Catholic social teaching and promote a peaceful transformation of society. The Catholic Worker was born.

A combination of the radical and the religious, The Catholic Worker challenged capitalism and the existing social order while remaining rooted in the Bible and Catholic teachings. Around the paper grew a national movement that combined works of mercy, such as feeding the hungry and housing the homeless in “hospitality houses,” with working actively for peace, labor and civil rights.

Unlike many charitable houses, the Catholic Worker houses made no attempt to convert those who came through its doors. When a social worker once asked Day how long “clients” were allowed to stay, Day responded, “We let them stay forever…Once they are taken in, they become members of the family. Or rather they always were members of the family. They are our brothers and sisters in Christ.”

What earned Day the greatest amount of criticism, but has proved to be her greatest contribution, was her commitment to pacifism. During the Spanish Civil War, the Catholic Church by and large threw its support behind Franco, the fascist who styled himself the defender of the Catholic faith. The Catholic Worker refused to support either side and lost two-thirds of its readership as a result. Throughout World War II, the Cold War, the Korean war and the Vietnam War, Day continued to speak out against violence, leading acts of civil disobedience and often getting arrested. During the 1950s, Day led the Catholic Worker community in its refusal to participate in civil defense drills. Day believed that preparing for nuclear attack promoted the belief that nuclear war was winnable and that it justified military spending. “We do not have faith in God if we depend upon the Atom Bomb,” one Catholic Worker leaflet explained.

In 1963 and 1965, Day traveled to Rome to encourage the Vatican to speak out against violence. She and her fellow pacifists had reason to celebrate when in December 1965 the Church issued the Constitution on the Church in the Modern World. The Constitution described any act of war that indiscriminately destroyed vast areas with their inhabitants as “a crime against God and humanity.” It also called for legal provisions for conscientious objectors while describing as “criminal” those who obey commands which condemn the innocent and defenseless.

For her achievements Day received many honors. As part of the Council of the Laity in 1967, she was one of two Americans invited to receive Communion from the hands of the Pope. For her 75th birthday, the Jesuit magazine America devoted a special issue to her, celebrating her as the individual who best exemplified “the aspiration and action of the American Catholic community during the past forty years.” Notre Dame University awarded her its Laetare Medal for “comforting the afflicted and afflicting the comfortable.” When she was no longer able to travel, she received a visit from Mother Teresa of Calcutta who pinned on her the cross worn only by fully professed Missionary Sisters of Charity.

Day passed away in 1980, and since her death she has been credited for restoring the Gospel’s teachings on nonviolence to a place of prominence within the Catholic Church. She once remarked, “If I have achieved anything in my life, it is because I have not been embarrassed to talk about God.” But more than that, she is one of the few who had the courage to act on their beliefs.

Loretta Brennan Glucksman

Keeping the Home Fires Burning

“I feel so welcomed and drawn in by my friends in Ireland. The more I know, the more I want to do.“

“There has not been a great tradition of giving to Ireland – possibly because no one has asked,” Loretta Brennan Glucksman once remarked. As national president of The American Ireland Fund, Glucksman has changed all that, and is personally leading a campaign to raise $100 million to promote peace, cultural, and business opportunities in Ireland.

Glucksman credits her husband Lewis as the inspiration behind her commitment to serving Ireland’s people. Together they donated $3 million to the center for Irish studies at New York University. Ireland’s universities have also benefited from the Glucksmans’ philanthropy including Trinity College, University of Limerick and University College Dublin.

Brennan Glucksman whose career has including teaching, television production and running her own public relations firm, also serves on the board of several Irish-related organizations including the Irish American Cultural Institute, Cooperation Ireland and the Ireland-U.S. Council for Commerce and Industry.

She and her husband have five children and five grandchildren. They reside in Manhattan and also keep a home in Ireland.

Father Edward Flanagan

Saving Grace

“There is no such thing as a bad boy.“

Spencer Tracy won an Academy Award for his stirring portrayal of Boys Town founder Father Edward Flanagan, but Flanagan surely earned something even greater for his three decades of public service: a place in heaven.

Born on July 13, 1896 in Leabeg, Co. Roscommon, Flanagan left Ireland for the States shortly after finishing high school in Silgo. His brother Patrick was a priest in Omaha, and Flanagan hoped to follow in his footsteps but it was to take longer than he anticipated. Poor health delayed his vocation by a couple of years, but he was finally ordained to the priesthood in 1912 in Innsbruck, Austria.

Within four years of his return to Omaha, he turned his eye to the disadvantaged youth of the area. In 1917 he opened his first shelter for less fortunate kids. Originally called Father Flanagan’s Boys’ Home, it soon became known as Boys Town, and moved to larger facilities in 1922. Several new branches were to pop up across the state as the reputation of Boys Town spread.

While Flanagan did not believe in spoiling his young charges, he was seen to really care for the youngsters, and he truly believed his oft-repeated maxim that there was “no such thing as a bad boy.” At the request of President Harry Truman, he traveled internationally to study problems of juvenile welfare. Among his stops were Japan, Korea, Austria and Germany. It was on May 15, 1948, during a visit to Berlin, that he died of a heart attack.

In 1979, some 30 years after Flanagan’s death, Boys Town finally caught up with the times, and young women began to be admitted. After his death the haven he established ceased to attract as much publicity, but Boys Town is still active today. Flanagan was buried at Boys Town’s Dowd Memorial Catholic Chapel, where his epitaph reads: “Father Flanagan, Founder of Boys Town, Lover of Christ and Man.”

John Cardinal O’Connor

Shepherd

“If my father had one passion above all else, it was one of justice toward the working man. That’s in my blood.“

When John Cardinal O’Connor was elevated to the position of Archbishop of New York in 1984, he was a breath of fresh air for many Irish Americans. His concern and active participation in the affairs of Northern Ireland ran counter to the widespread sentiment that the Catholic Church in the U.S. had withdrawn from any substantial involvement. His refusal to be cowed by politicians assured Irish Americans that in O’Connor they had a genuine ally.

Two examples stand out in particular: the Joe Doherty case and the 1985 New York St. Patrick’s Day parade. Joe Doherty, a member of the IRA had been arrested in New York and held on an extradition warrant. Once, when Doherty was transferred to a remote prison in upstate New York, away from his friends and lawyers, it was O’Connor who demanded, and got, his return to New York City.

When Peter King, then comptroller of Nassau County, and a supporter of Sinn Féin and Noraid, was elected grand marshal of the St. Patrick’s Day Parade in 1985, the Irish government tried to persuade O’Connor to boycott the parade. But the Cardinal clearly saw that his responsibility was to the people of New York, not a foreign government, and he participated in the parade after all.

Under O’Connor’s leadership, the Archdiocese of New York has been the quickest to respond to the plight of illegal Irish immigrants, providing free counseling, medical care and social services.

Even though outspoken in his conservative views, he has won the respect of many liberals, including Paul O’Dwyer, the human rights advocate. “The strength of his leadership, so freely given in freedom’s name, was never more needed,” he once said. “His example lit the way for the timid and the fearful.”

O’Connor was born in Scranton, Pennsylvania, and his childhood was once described as that of a “typical poor Irish kid of the Depression.” His father, Thomas, the son of Roscommon immigrants, was very passionate about his Irish heritage. In an interview with Irish America magazine, O’Connor recalled, “You’d have thought Parnell was his brother-in-law the way he talked about him.”

O’Connor’s own interest in Ireland expanded while he was in the seminary. He read the works of Padraig Pearse, Joseph Mary Plunkett and Padraic Colum and the Irish poets of the time. As he rose through the ecclesiastical ranks, he visited his relatives in Ireland several times. Since being appointed Cardinal he has also traveled to Ireland as chairman of the committee for social developments and world peace of the National Conference of Bishops.

From 1979 to 1983, O’Connor served as bishop at the military vicariate in New York City. He spent a year as Bishop of Scranton, Pennsylvania before being called to return to New York to succeed Cardinal Cooke. And he wasted no time in distinguishing himself as a sincere and powerful advocate to New York Irish Americans.

Paul O’Dwyer

Civil Rights Champion

“If you take my kind of position you expect to be defeated much of the time. It’s as simple as that.“

Paul O’Dwyer was one of this century’s most outspoken, progressive defenders of the cause of civil rights and justice, continually standing up in defense of the downtrodden, regardless of race, gender or creed. He was also a driving force behind the election of David Dinkins as New York City’s first Black mayor.

New York and all of Irish America lost one of its heroes on June 26, 1998 when O’Dwyer passed away. Time and again he stood up for what was right, regardless of the personal cost he would suffer. At the height of the Cold War when the country was seized by the red scare, O’Dwyer was accused of having “Red sympathies” for speaking out against the “national witch-hunt” and for defending people accused of Communist sympathy.

His next battle was for the civil rights movement. In 1963, he was asked by the NAACP to defend a college teacher accused of inciting riot. O’Dwyer argued that her arrest violated her civil rights, and she was freed on a reduced charge. He also participated in the drive to give the vote to black residents of Mississippi.

In the late 1960s, O’Dwyer once again found himself at odds with the political establishment in his vigorous opposition to the Vietnam War. His stance cost him a U.S. Senate seat when he was branded as unpatriotic.

In spite of opposition from regular Democrats and The New York Times, O’Dwyer won the seat of City Council President in 1973 after the reform Democrats, trade unions and the Irish weeklies and minority papers rallied to support him.

Born in the parish of Bohola, County Mayo, O’Dwyer grew up during a time of immense turmoil in Ireland, the Easter Rising, the Black and Tan war, the partition of Ireland and the subsequent Civil War.

The youngest of eleven children, he immigrated to New York City in the spring of 1925. He had been preceded by his four brothers, one of whom, Bill, he had never even met.

One year after his arrival, Paul O’Dwyer enrolled in St. John’s University Law School, paying his way with some assistance from his brothers and out of his wages working in the shipping department of a silk mill. He was admitted to the bar in 1931 and went on to become a partner in the prestigious New York law firm O’Dwyer and Bernstien.

Throughout his long career, O’Dwyer championed the underdog. Back in Ireland he co-founded the Cheshire Homes to look after handicapped children and adults. The center in his native Bohola was a particular delight to him.

O’Dwyer helped supply the Irgun in the battle for the creation of Israel. He represented the Iranian government after the Ayatollah Khomeini took power when no one would represent them; he made an issue of the rights of Native Americans; and of course, in his beloved Ireland he fiercely proclaimed the right to Irish unity. His republicanism however, did not stop him from being a pioneer in reaching out to loyalists and he helped draft the seminal Ulster Defense Association document “Common Ground” which played a major role in the politicization of paramilitary loyalism in Northern Ireland.

His brother Bill was Mayor of New York and later Ambassador to Mexico. Paul O’Dwyer died on June 26, 1998 in New York. At his wake his nephew Frank Durkan, also a civil rights attorney, said simply, “The fire never went out.”

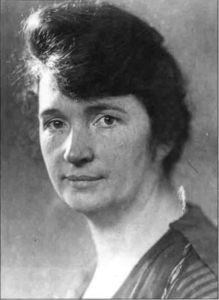

Margaret Higgins Sanger

Birth Control Pioneer

“No woman can call herself free until she can choose consciously whether she will or will not be a mother.“

Historian H.G. Wells, writing in 1931, said: “When the history of our civilization is written, it will be a biological history, and Margaret Sanger will be its heroine.”

Like many Irish and Irish American working- and middle-class women of her time, Anne Purcell Higgins had a tough life, gradually worn down by 18 pregnancies and the birth of 11 living children. She died at the young age of 40. This dilemma had a profound affect on her sixth child, Margaret, who would go on to do sterling work in family planning and on behalf of women everywhere.

Born September 4, 1879 in Coming, New York, to Irish American Anne Purcell and Irish immigrant stone mason Michael Hennessy Higgins, young Margaret attended college in the Catskills and went on to train as a nurse at White Plains Hospital. Her first marriage, to architect William Sanger, ended in divorce after 18 years and three children. She subsequently married millionaire J. Noah Slee.

But Sanger was far from a lady of leisure, as she could well have afforded to be. She became active in socialism and the women’s labor movement in 1912, and worked like a Trojan in the tenements of New York’s Lower East Side, an experience which opened her eyes to the connection between poverty, premature death and lack of family planning.

It was Sanger who coined the term “birth control,” and she was one of the most vociferous advocates for the legalization of contraception. In 1916, with the help of her sister Ethel Byrne, Sanger opened a birth control clinic in Brooklyn, a “crime” which earned her a 30-day prison sentence. Her second husband’s wealth aided her in the establishment of the American Birth Control League and the Birth Control Research Bureau. In 1942, these two organizations came together to form Planned Parenthood, a group which is still going strong today. Sanger was also behind the development of a contraceptive pill.

Sanger died on September 6, 1966, less than a year after the Supreme Court had repealed a Connecticut law that prohibited the use of contraception by married couples.

Margaret Tobin Brown

The Unsinkable Molly Brown

“I’m unsinkable.“

Margaret Tobin Brown was reading a book in her first-class cabin on the Titanic when she heard a crash and was thrown to the floor by the impact. Pulling herself up, she went out into the corridor to investigate and saw her fellow passengers standing around in their nightwear. It was then she noticed that the engines had stopped. She went up on deck and was flung into a lifeboat with thirteen other people, three men and ten women. Amid the confusion and fear, Maggie promptly took command, organizing the other passengers of the small boat to row and buoying their spirits with her indomitable personality.

After her boat was picked up by the Carpathia shortly after dawn the next day, Maggie continued to help with rescue efforts. She also helped to form a committee of other wealthy survivors to help destitute victims of the disaster. Even before the Carpathia docked in New York, she had nearly $10,000 worth of pledges.

When she finally arrived in New York, she told a reporter that she attributed her survival to “typical Brown luck…We’re unsinkable.” Years later, she gained the nickname “Molly Brown,” and was immortalized as “The Unsinkable Molly Brown” in Meredith Willson’s Broadway musical.

The daughter of Irish immigrants, Brown was born Margaret Tobin on July 18, 1867 in Hannibal, Missouri. She received little formal education and found work in her early teens as a waitress. Around 1884, she moved to Leadville, Colorado, after having purportedly been told by one of her customers, Samuel Clemens (Mark Twain), about the wealth that could be found in the Rockies. In Leadville, she met James Joseph (J.J.) Brown, the manager of a silver mine. The two married in 1886 and had two children, Helen and Lawrence.

J.J. made a small fortune in a gold find and he and Maggie moved to Denver. Maggie sought to enter Denver society but met with little success. After she and her husband separated, she began traveling throughout Europe with her son, Lawrence, where through her persistence and flamboyant personality she gained acceptance into the society of a group of wealthy Americans.

In 1912, she was touring Europe when she received word that her grandson, Lawrence Palmer, Jr., was ill. Brown immediately made arrangements to return to the States, booking her passage on the Titanic.

After the disaster, Brown used her money and newfound fame on behalf of a variety of causes, including women’s suffrage and local Catholic charities. She also led one of Denver’s first preservation projects when she spearheaded the movement to save the home of Denver poet Eugene Field. She even ran for the U.S. Senate three times, failing to win each time. Brown’s declining years were spent traveling between Denver, New York and Newport, Rhode Island. At age 65, she suffered a stroke and died on October 26, 1932 at New York’s Barbizon Hotel.

Editor’s Note: This article was originally published in the November 1999 issue of Irish America. ⬥

Leave a Reply