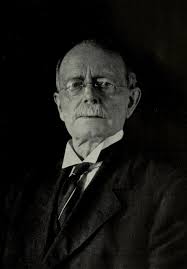

Henry Ford

King of the Road

“Failure is only the opportunity to begin again more intelligently.”

He changed the future of this country, and indeed the world, with his revolutionary line of stylish, affordable motor cars. Today the name Ford is synonymous with quality, safety and value for money. He wouldn’t have had it any other way.

Born July 30, 1863, Henry Ford was the oldest of Michigan farmers William and Mary Ford’s six children. His father was a Famine emigrant from Cork who had almost drowned on the passage over when he was swept overboard. Ford discovered at an early age that he was more interested in how his family’s farm machinery worked than actually using them for chores. At 16, he worked as a machinist’s apprentice. Later, he operated and repaired steam engines, overhauled his father’s farm implements, and supported himself and his new wife by running a sawmill.

In 1891, Ford became an engineer and created the Ford Motor Company in 1903. The Model T ushered in a new era of personal transportation with its ease of operation, maintenance, and maneuverability. By 1918, half of all cars in America were Model Ts. Ford’s implementation of the assembly line revolutionized automobile production by significantly reducing assembly time per vehicle, and thus lowering costs — savings Ford continually passed on to the public. Prices fell as fast as sales rose, dropping from barely under $1,000 in 1909 to $355 (roughly $2,800 today) by 1920.

Ford’s revolutionary vision included hiring thousands of handicapped workers, including bedridden patients who screwed nuts and bolts together in mini-assembly lines in their rooms. He believed this issue, along with minimum wages, maximum working hours, and the production pace, were the responsibility of entrepreneurs, not government. He said: “Our help does not come from Washington, but from ourselves. The government is a servant and never should be anything but a servant.”

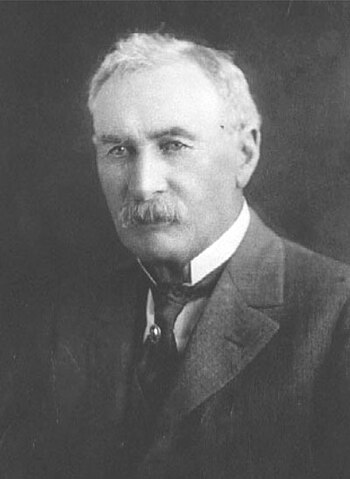

John Philip Holland

Ideas Man

“Mr. Holland climbed in, closed the hatch and started the engine … and before we realized it the boat was under twelve feet of water.” – Mr. Dunherly, Holland’s engineer

As the inventor of the submarine, he changed the way naval warfare was conducted forever. He secured the first investment for his “submersible vessel” from the Irish Republican Brotherhood, who hoped to use the craft against England, but ironically ended up being commissioned to design two submarines for the Japanese during their war against Russia. It took eight years before he saw his first vessel launched successfully, but John Holland will forever be known as the “father” of the modern submarine.

Born February 29, 1840, in Liscannor, County Clare, to John Holland and Mary Scanlon, Holland began his career as a teacher. Reading about underwater transport and the works of various inventors, he became fascinated with the whole concept, and worked on the problem until he finally came up with his own design in 1870.

Needing financial backing, Holland moved to the U.S. and settled in New Jersey in 1873, where he taught until 1879. The IRB supplied him with $23,000 for his efforts, and the aptly named Fenian Ram, at 30 feet long and six feet wide, looked promising during test runs. The vessel managed to stay submerged for an hour at a depth of 60 feet. Writing about its launch, U.S. Admiral Philip Hichborn noted that “after the completion of this boat, Holland led the world far and away in the solution of submarine problems.”

Holland’s next move was to work on improving his design, but when the next vessel was constructed without his direct supervision it was badly damaged on its launch. In 1895, Holland’s company won its first contract from the U.S. Navy to build a submarine, but after supervision of the project was handed over to a Navy admiral, the craft failed.

The astute inventor, not to be dissuaded, began to work on his own vessel in New Jersey, and its success inspired the federal government to quickly hand in an order for six more. Orders followed from all over the world, and Holland’s reputation was secured.

He was married to Margaret Foley and the couple had four children. Holland died on August 12, 1914.

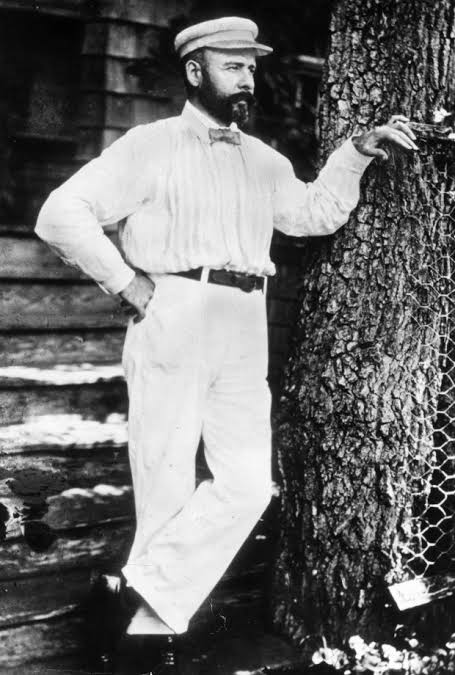

Louis Henri Sullivan

King of the Sky

“Form ever follows function, and this is the law. Where function does not change, form does not change.”

His pioneering work in the field of high-rise design cannot be overestimated, and he is remembered as the creator of one of the world’s first skyscrapers. Louis Henri Sullivan, together with engineer partner Dankmar Adler, was responsible for such notable buildings as the Auditorium and Stock Exchange buildings in Chicago and the Wainwright Building in St. Louis.

History has long recognized the contribution of the Irish to the building of American infrastructure, whether it be roads, canals, skyscrapers or churches. But Sullivan was the Irish American whose contribution to the skylines of various cities climbs tallest of all.

Born September 3, 1856 in Boston, Massachusetts, to Patrick Sullivan and Adrienne List, Sullivan was raised on the farm belonging to his maternal grandparents. His father was a dancing instructor who had immigrated from Cork; his mother had also recently arrived in the States from Geneva with her parents, and was of French, German and Swiss ancestry.

Sullivan did not have a close relationship with his father, and wrote in his memoir that Sullivan senior was “a free-mason and not even sure he was a Catholic or an Orangeman.” However, according to an article by Adolf K. Placzek, the young Louis Sullivan was “the most Celtic of Celts, if there is such a thing.”

After studying at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Sullivan served apprenticeships with architects in Philadelphia and Chicago. He also studied in Paris for a year, but returned to Chicago where, in 1881, he established Adler and Sullivan. In what was to be an extremely efficient partnership, Sullivan designed the buildings (over 100 in all) and Adler built them.

Among Sullivan’s young associates was Frank Lloyd Wright who once described himself as the “pencil in Sullivan’s hand.” The relationship between the two was at times stormy, however, and when Sullivan discovered that Wright was moonlighting on different projects, he fired the younger man. “This bad end to a glorious relationship,” remarked Wright, “has been a dark shadow to stay with me the days of my life.”

Towards the end of the 19th century, architectural taste returned to neoclassicism, a trend Sullivan was unwilling to follow. In 1895, he and Adler went their separate ways, and Sullivan turned his attention to smaller buildings in small towns. He also authored two books on architecture — Autobiography of an Idea and Kindergarten Chats and Other Writings. He died in a Chicago hotel room on April 14, 1924, separated from his wife and virtually bankrupt.

William Mulholland

Water Titan

“There it is. Take it!“

His methods may have brought him in for some sharp criticism, but William Mulholland changed the way the Los Angeles of the late 1800s looked, and ensured that the City of Angels would prosper forevermore. A self-made man, Mulholland achieved this by rerouting the Owens River, sited more than 200 miles from L.A., in the process creating one of the engineering marvels of its time.

Born in Belfast in 1855, Mulholland was raised in Dublin. He left home when he was 15 and arrived in New York in the early 1870s. Working his way across the country, he arrived in San Francisco in 1877, and shortly afterwards moved to L.A.

Within eight years of being hired as a ditch-cleaner at a private water company, Mulholland had risen to the post of superintendent. After the city took over the company, he was made head of the Department of Water and Power, a position he remained in until 1928.

As the city continued to boom, Mulholland and a former L.A. mayor named Fred Eaton became convinced that more water would be needed to sustain growth. The Owens River looked like L.A.’s best chance of survival and in 1905, Mullholland began organizing the construction of the Los Angeles Aqueduct, which when built was considered second only to the Panama Canal as an engineering masterpiece. On November 5, 1913 Mullholland raised the Stars and Stripes and before a crowd of 40,000 onlookers opened the metal gates. As the water flooded through he spoke the memorable words, “There it is. Take it!”

While he deserves credit for this feat, and for his work in securing the continued prosperity of Los Angeles, the resulting drain on Owens Valley resources left local farmers reeling, and they united to fight back, blowing up the Los Angeles Aqueduct at a critical point. They also commandeered control of an aqueduct gate, earning the support of media outlets from as far away as Paris. When their battle ran out of steam, Mulholland’s woes looked like they were over.

It was to be a temporary reprieve, however. On March 12, 1928, the St. Francis Dam collapsed, resulting in a 15-billion-gallon flood that killed almost 500 men, women and children. Mulholland, who had supervised construction of the dam, was held accountable for the disaster by a board of inquiry and forced to resign. He died in 1935.

Leave a Reply