Pete Hamill writes on JFK

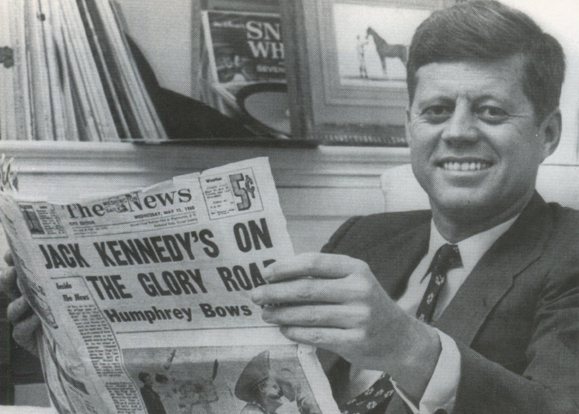

Somewhere in the shadowy land between myth and history lies the domicile of John F. Kennedy. The first United States president of Irish-Catholic descent, Kennedy was a man of many faces: war hero, orator, lover, creator, and visionary. He had it all, and it was all taken away, but in the end he gained immortality.

That day I was in Ireland, in the dark, hard northern city of Belfast. I was there with my father, who had been away from the city where he was born for more than 30 years. He was an American now: citizen of Brooklyn, survivor of the Depression and poverty, one leg lost on an American playing field in the late 1920s, playing a game learned in Ireland, father of seven children, fanatic of baseball. But along the Falls Road in Belfast in November 1963, he was greeted as a returning Irishman by his brother Frank and his surviving Irish friends, and there were many Irish tears and much Irish laughter, waterfalls of beer, and all the old Irish songs of defiance and loss. Billy Hamill was home. And on the evening of November 22, I was in my cousin Frankie Bennett’s house in a section called Andersonstown, dressing to go down to see the old man in a place called the Rock Bar. The television was on in the parlor. Frankie’s youngest kids were playing on the floor. A frail rain was falling outside.

And then the program was interrupted and a BBC announcer came on, his face grave, to say that the president of the United States had been shot while riding in a motorcade in Dallas, Texas. Everything in the room stopped. In his clipped, abrupt voice, the announcer said that the details were sketchy. Everyone turned to me, the visiting American, a reporter on a New York newspaper, as if I would know if this could possibly be true. I mumbled, talked nonsense – maybe it was a mistake; sometimes breaking news is moved too fast – but my stomach was churning. The regular program resumed; the kids went back to playing. A few minutes later, the announcer returned, and this time his voice was unsteady. It was true. John F. Kennedy, the president of the United States, was dead.

I remember whirling in pain and fury, slamming the wall with my open hand, and reeling out into the night. All over the city, thousands of human beings were doing the same thing. Doors slammed and sudden wails went up. Oh, sweet Jesus, they shot Jack! and They killed President Kennedy! and He’s been shot dead! At the foot of the Falls Road, I saw an enraged man punching a tree. Another man sat on the curb, sobbing into his hands. Trying to be a reporter, I wandered over to the Shankill Road, the main Protestant avenue in that city long ghettoized by religion and history. There was not yet a Peace Line; not yet any British troops hovering warily on the streets, no bombs or ambushes or bloody Sundays. The reaction was the same on the Shankill as it was on the Falls. Holy God, they’ve killed President Kennedy: with men weeping and children running aimlessly with the news and bawling women everywhere. It was a scale of grief I’d never seen before or since in any place on earth. That night, John Fitzgerald Kennedy wasn’t “the Catholic president” to the people of the Shankill or the Falls; he was the young and shining prince of the Irish diaspora.

After an hour, I ended up at the Rock Bar, climbing a flight of stairs to the long, smoky upstairs room. The place was packed. At a corner table, my father was sitting with two old IRA men; one had only two fingers on his right hand. They were trying to console him when he was beyond consolation. His grief was real. No wonder. For the Catholic immigrants of his generation, men and women born in the first decade of the century, Jack Kennedy was forever and always someone special. His election in 1960 had redeemed everything: the bigotry that went all the way back to the Great Famine; the slurs and the sneers; Help Wanted, No Irish Need Apply; the insulting acceptance of the stereotype of the drunken and impotent Stage Irishman; the doors closed in law firms, and men’s clubs, and brokerage houses because of religion and origin. After 1960, they knew that their children truly could be anything in their chosen country, including the president of the United States.

After an hour, I ended up at the Rock Bar, climbing a flight of stairs to the long, smoky upstairs room. The place was packed. At a corner table, my father was sitting with two old IRA men; one had only two fingers on his right hand. They were trying to console him when he was beyond consolation. His grief was real. No wonder. For the Catholic immigrants of his generation, men and women born in the first decade of the century, Jack Kennedy was forever and always someone special. His election in 1960 had redeemed everything: the bigotry that went all the way back to the Great Famine; the slurs and the sneers; Help Wanted, No Irish Need Apply; the insulting acceptance of the stereotype of the drunken and impotent Stage Irishman; the doors closed in law firms, and men’s clubs, and brokerage houses because of religion and origin. After 1960, they knew that their children truly could be anything in their chosen country, including the president of the United States.

“They got him, they got him,” my father said that night, embracing me and sobbing into my shoulder. “The dirty sons of bitches, they got him.”

And then “The Star-Spangled Banner” was playing on the television set, and everyone in the place, a hundred of them at least, rose at once and saluted. They weren’t saluting the American flag, which was superimposed over Kennedy’s face. They were saluting the fallen president who in some special way was their president too. The anthem ended. We sat down in a hushed way and drank a lot of whiskey together. We watched bulletins from Dallas. We cursed the darkness. And then there was a film of Kennedy in life. Visiting Ireland for three days the previous June.

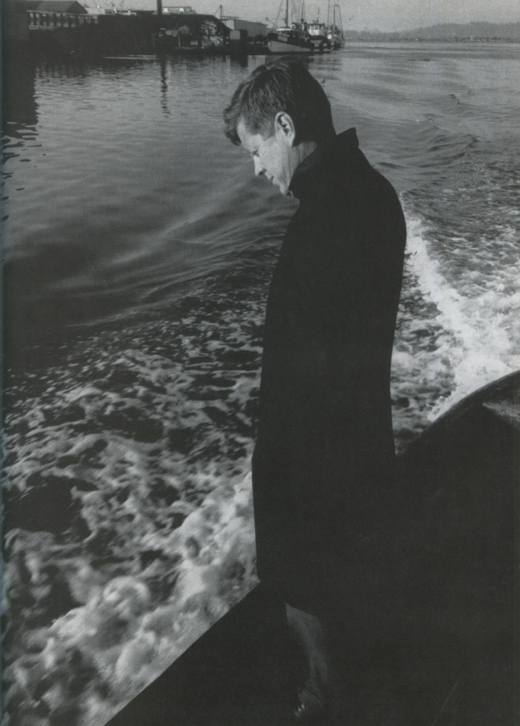

There he was, smiling in that curious way, at once genuine and detached, capable of fondness and irony. The wind was tossing his hair. He was playing with the top button of his jacket. He was standing next to Éamon de Valera, the aged and gravely formal president of Ireland. Jack Kennedy was laughing with the mayor of New Ross in County Wexford. He was being engulfed by vast crowds in Dublin. He seemed to be having a very good time. And then he was at the airport to say his farewell, and in the Rock Bar, we heard him speak:

“Last night, somebody sang a song, the words of which I’m sure you know, of ‘Come back to Erin, mavourneen, mavourneen, come back aroun’ to the land of thy birth. Come with the shamrock in the springtime, mavourneen.'” He paused, but did not laugh at the sentimentality of the words; he seemed rather to be feeling the sentiment itself, the truth beneath the words, the ineradicable tearing that goes with exile. “This is not the land of my birth, but it is the land for which I hold the greatest affection.” Another pause and then a smile. “And I certainly will come back in the springtime.”

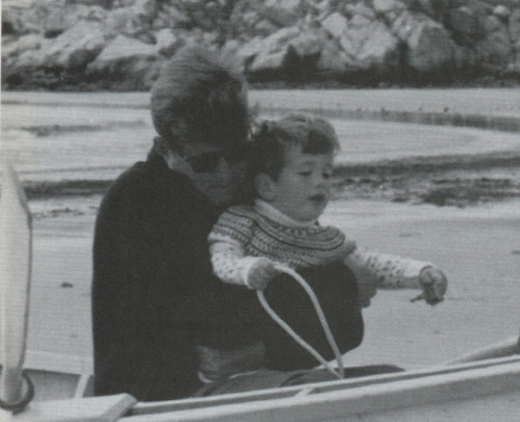

Thirty-six springtimes have come and gone, and for those of us who were young then, those days live on in vivid detail. We remember where we were and how we lived and who we were in love with. We remember the images on television screens, black-and-white and grainy: Lee Harvey Oswald dying over and over again as Jack Ruby steps out to blow him into eternity; Jacqueline Kennedy’s extraordinary wounded grace; Caroline’s baffled eyes and John-John saluting. We remember the drumrolls and the riderless horse.

Thirty-six springtimes have come and gone, and for those of us who were young then, those days live on in vivid detail. We remember where we were and how we lived and who we were in love with. We remember the images on television screens, black-and-white and grainy: Lee Harvey Oswald dying over and over again as Jack Ruby steps out to blow him into eternity; Jacqueline Kennedy’s extraordinary wounded grace; Caroline’s baffled eyes and John-John saluting. We remember the drumrolls and the riderless horse.

Irish Americans of a certain age will carry those images to their graves. At the end of a century that began with much poverty and even more hope, the immigrants who are still alive and the children who are charged with remembering have much reason to rejoice. There are few doors any longer closed to Irish Americans. Irish Americans run vast corporations, control great wealth, have triumphed in every field in American life, from the great universities to the halls of Congress, from movies and television to journalism and literature. We have our scientists, our doctors, our athletes, our scholars. Irish Americans can say with confidence: we have won all the late rounds.

The turning point, it seems to me, was the election of John F. Kennedy. Or rather, the election and the assassination a thousand days later. The combination ended the last vestiges of the marginalizing of Irish Americans; the hyphen that so infuriated Kennedy’s father was permanently removed, (who refers to Mark McGwire as an Irish-American?) or altered into an identity card that suggests admission, not exclusion; welcome, not rejection. The traumatic shock of the assassination itself created subtle shifts in the ways that other Americans perceived Irish Americans: there was a sense of dues paid, of finality. Many glib assumptions were shot away with that Mannlicher Carcano rifle. Among them were the assumptions of the larger society, expressed in the shorthand of stereotypes. But Kennedy’s moment also ended the more timid assumptions of too many Irish men and women who believed that a desire for personal excellence or worldly success was a surrender to the sin of pride. They had created for themselves and their children what I’ve called elsewhere the Green Ceiling; Jack Kennedy smashed that ceiling forever. After he was buried, the men and women he had inspired did not go away.

To be sure, across those 36 springtimes, there have been alterations made – some of them drastic – to the reputation of John Fitzgerald Kennedy. Those who hated him on November 21, 1963, did not stop hating him on November 23; many carried their hatred to their own graves. Some who were once his partisans mined upon him with the icy retrospective contempt that is the specialty of the neoconservative faith. And time itself has altered his once-glittering presence in the national consciousness. An entire generation has come to maturity with no memory at all of the Kennedy years; for them, Kennedy is the name of an airport or a boulevard or a high school.

Certainly, the psychic wound of his sudden death triggered the Sixties, that era that did not end until Richard Nixon waved his awkward farewells and the North Vietnamese tanks rolled into the presidential palace in Saigon. Only a handful of addled right-wingers continue fighting over the Sixties. The revisionists have come forward; Kennedy’s life and his presidency have been examined in detail, and for some, both have been found wanting. The Kennedy presidency, we have been told, was incomplete, a sad perhaps; the man himself was deeply flawed. Some of this analysis was a reaction to the overwrought mythologizing of the first few years after Dallas. The selling of “Camelot” was too insistent, too fevered, accompanied by too much sentimentality and too little rigorous thought. The Camelot metaphor was never used during Kennedy’s 1,000 days (Jack himself might have dismissed the notion with a wry or obscene remark); it first appeared in an interview Theodore H. White did with Jacqueline after the assassination. But it pervaded many of the first memoirs about the man and his time.

Some of the altered vision of Kennedy came from the coarsening of the collective memory by the endless stream of books about the assassination itself. The murder was submerged to a welter of conspiracy theories. In the end, nothing has been resolved. If there was a conspiracy, the plotters got away with it. In a peculiar way, the details of Kennedy’s death obliterated both the accomplishments and failures of his life.

Some of the altered vision of Kennedy came from the coarsening of the collective memory by the endless stream of books about the assassination itself. The murder was submerged to a welter of conspiracy theories. In the end, nothing has been resolved. If there was a conspiracy, the plotters got away with it. In a peculiar way, the details of Kennedy’s death obliterated both the accomplishments and failures of his life.

Other tales have helped to debase the metal of the man: the smarmy memoirs of women who certainly slept with him and others who certainly didn’t; the endless retailing of the gossip about his alleged affair with Marilyn Monroe, that other pole of American literary necrophilia; the detailed histories of the family and its sometimes arrogant ways. He was described in some gossip as a mere “wham, bam, thank you, ma’am” character; other talk had him a hopeless romantic. By all accounts, he was attracted to beautiful and intelligent women, and many of them were attracted to him. And during the time he journeyed among us, this was hardly a secret. When I was a young reporter for the Post in late 1960, I was once assigned to cover Jack Kennedy during one of his stays at the Carlyle hotel. He had been elected but had not yet taken office. “We hear he brings the broads in two at a time,” the editor said. “See what you can see.”

There was nothing to see that night, perhaps because of my own naïve incompetence as a reporter, or because I was joined in my vigil by another dozen reporters and about a hundred fans who wanted a glimpse of John F. Kennedy. Most likely, Kennedy was asleep in his suite while we camped outside the hotel’s doors. But I remember thinking this was the best news I’d ever heard about a president of the United States. A man who loved women would not blow up the world. Ah, youth.

Two other events helped eclipse the memory of Jack Kennedy. One was the rise of Robert Kennedy, and his assassination in 1968. The other was Chappaquiddick. Some who had been drawn to politics by Jack Kennedy at last began to retreat from the glamour of the myth. A few turned away in revulsion, seeing after Chappaquiddick only the selfish arrogance of privilege. Others faded into indifference or exhaustion. At some undefined point in the late 1970s, the country seemed to decide it wanted to be free of the endless tragedy of the Kennedys. Even the most fervent Kennedy partisans needed release from doom and death. They left politics, worked in the media or the stock market or the academy. A few politicians continued to chase the surface of the myth; Gary Hart was one of them; in a different way, so was Bill Clinton. They helped cheapen Jack Kennedy’s image the way imitators often undercut the work of an original artist.

Out in the country, beyond the narrow parish of professional politics, the people began to look for other myths and settled for a counterfeit. It was no accident that if once they had been entranced by a president who looked like a movie star, then the next step would be to find a movie star who looked like a president. The accidental charisma of Jack Kennedy gave way to the superb professional performance of Ronald Reagan.

Out in the country, beyond the narrow parish of professional politics, the people began to look for other myths and settled for a counterfeit. It was no accident that if once they had been entranced by a president who looked like a movie star, then the next step would be to find a movie star who looked like a president. The accidental charisma of Jack Kennedy gave way to the superb professional performance of Ronald Reagan.

The mistakes and flaws of the Kennedy presidency are now obvious. Domestically, he often moved too slowly, afraid of challenging Congress, and somewhat late to recognize the urgency of the civil rights movement, which had matured on his watch. He understood the fragility of the New Deal coalition of northern liberals and southern conservatives; he had been schooled in the traditional ways of compromise in the House and Senate and was always uneasy with the moral certainties of “professional liberals.” When faced with escalating hatred and violence in the South, Kennedy did respond; he showed a moral toughness that surprised his detractors and helped change the region. But he was often bored with life at home.

Foreign policy more easily captured his passions. He was one of the few American presidents to have traveled widely, to have experienced other cultures. His style was urban and cosmopolitan, and he understood that developments in technology were swiftly creating what Marshall McLuhan was to call the “global village.” But since Kennedy had come to political maturity in the fifties, he at first accepted the premises of the Cold War and the system of alliances and priorities that had been shaped by John Foster Dulles.

Even today, revisionists of the left seem unable to forgive the role that Kennedy the Cold Warrior played in setting the stage for the catastrophe of Vietnam. He had inherited from Eisenhower a commitment to the Diem regime, and as he honored that commitment, the number of U.S. “advisers” grew from 200 to 16,000. By most accounts, Kennedy intended to end the American commitment to South Vietnam after the 1964 election. But since he’d won in 1960 by only 118,000 votes, he didn’t feel he could risk charges by the American right that he had “lost” Vietnam. The quagmire beckoned, and at his death, Kennedy still hadn’t moved to prevent the United States from trudging onward into the disaster.

For most of Kennedy’s two years and ten months as president, Vietnam was a distant problem, simmering away at the back of the stove. Kennedy’s obsession was Cuba. It remains unclear how much he knew about the various CIA plots to assassinate Fidel Castro. But the two major foreign-policy events of his presidency were the Bay of Pigs invasion of April 1961 and the missile crisis of October 1962. One was a dreadful defeat, the other a triumph.

According to Richard Goodwin and others (I remember discussing this with Robert Kennedy), Jack Kennedy had begun the quiet process of normalizing relations with Castro before his death. Although this, too, was to be postponed until after the 1964 elections, Kennedy had come to believe that Cuba was not worth the destruction of the planet. He waited, a prisoner of caution, and Fidel Castro — seven presidents later — is still the ruler of Cuba.

Today, it’s hard to recall the intensity of the Cuban fever that so often rose in the Kennedy years. I remember being in Union Square when the Brigade was going ashore. A week earlier, I’d actually applied for press credentials for the invasion from some anti-Castro agent in midtown; with great silken confidence, he told me I could go into Cuba after the provisional government was set up, a matter of a few days after the invasion. But from the moment it landed, the quixotic Brigade was doomed. And in Union Square on the second night, when it still seemed possible that the Marines would hurry to the rescue, there was a demonstration against Kennedy, sponsored by a group that called itself the Fair Play for Cuba Committee. Its members chanted slogans against the president. A year later, a much larger group demonstrated during the missile crisis. In a strange, muted way, these were the first tentative signals that the Sixties were coming. And later, after Dallas, when the world was trying to learn something about Lee Harvey Oswald, we all saw film of him on a New Orleans street corner, handing out leaflets. They were, of course, from the Fair Play for Cuba Committee.

Today, it’s hard to recall the intensity of the Cuban fever that so often rose in the Kennedy years. I remember being in Union Square when the Brigade was going ashore. A week earlier, I’d actually applied for press credentials for the invasion from some anti-Castro agent in midtown; with great silken confidence, he told me I could go into Cuba after the provisional government was set up, a matter of a few days after the invasion. But from the moment it landed, the quixotic Brigade was doomed. And in Union Square on the second night, when it still seemed possible that the Marines would hurry to the rescue, there was a demonstration against Kennedy, sponsored by a group that called itself the Fair Play for Cuba Committee. Its members chanted slogans against the president. A year later, a much larger group demonstrated during the missile crisis. In a strange, muted way, these were the first tentative signals that the Sixties were coming. And later, after Dallas, when the world was trying to learn something about Lee Harvey Oswald, we all saw film of him on a New Orleans street corner, handing out leaflets. They were, of course, from the Fair Play for Cuba Committee.

During his years in power, as far as I can tell, John Fitzgerald Kennedy never uttered a word about Northern Ireland.

And yet…

And yet, across the years, learning all of these things from the memoirs and biographies and histories, understanding that Camelot did not exist and that Jack Kennedy was not a perfect man, why do I remain moved almost to tears when a glimpse of him appears on television or I hear his voice coming from a radio?

I can’t explain in any rational way. I’ve tried. Hell, yes, I’ve tried. I’ve talked to my daughters about him, and to my wife Fukiko, after they’ve seen me turning away from some televised image of Jack. They’ve seen me swallow, or take a sudden breath of air, or flick away a half-formed tear. They know me as an aging skeptic about the perfectibility of man, a cynic about most politicians. I bore them with preachments about the need for reason and lucidity in all things. And then, suddenly, Jack Kennedy is speaking from the past about how the torch has passed to a new generation of Americans, born in this century, tempered by war, disciplined by a hard and bitter peace – and I’m gone.

There is more operating here for me (and for so many millions of others) than simple nostalgia for the years when I was young. Nothing similar happens when I see images of Harry Truman or Dwight Eisenhower. Jack Kennedy was different. He was at once a role model, a brilliant son or an older brother, someone who made us all feel better about being Americans. Not just those of us who are products of the Irish diaspora. All of us. Everywhere on the planet in those years, the great nations were led by old men, prisoners of history, slaves to orthodoxy. Not us (we thought, in our youthful arrogance). Not now.

“Ask not what your country can do for you,” Kennedy said. “Ask what you can do for your country.”

The line was immediately cherished by cartoonists and comedians, and Kennedy’s political opponents often threw it back at him with heavy sarcasm. But the truth was that thousands of young people responded to the call. The best and the brightest streamed into Washington, looking for places in this shiny new administration. They came to Kennedy’s Justice Department and began to transform it, using the power of law to accelerate social change, particularly in the South. They were all over the regulatory agencies. And after Kennedy started the Peace Corps, they signed up by the tens of thousands to go to the desperate places of the world to help strangers. It’s hard to explain to today’s young Americans that not so long ago, many people their age believed that the world could be transformed through politics. Yes, they were naïve. Yes, they were idealists. But we watched all this, and many of us thought, ‘This is some god-damned country.’

Out there in the wider world, people were responding to him as we were. It wasn’t just Ireland or Europe. I remember seeing the reports of his 1962 trip to Mexico City, where a million people came out to greet him, the women weeping, the men applauding him as fellow men and not inferiors. I’d lived in Mexico and knew the depths of resentment so many Mexicans felt toward the Colossus of the North. In one day, Kennedy seemed to erase a century of dreadful history. The same thing happened in Bogotá and Caracas where four years earlier Richard Nixon had been spat upon and humiliated. This was after the Bay of Pigs. This was while the Alliance for Progress was still trying to get off the ground. I can’t be certain today what there was about him that triggered so much emotion; surely it must have been some combination of his youth, naturalness, machismo, and grace. I do know this: In those years, when we went abroad, we were not often forced to defend the president of the United States.

We didn’t have to defend him at home, either. He did a very good job of that himself. We hurried off to watch his televised press conferences because they were such splendid displays of intelligence, humor, and style. We might disagree with Kennedy’s policies, and often did; but he expressed them on such a high level that disagreement was itself part of an intelligent process instead of the more conventional exchange of iron certitudes. He held 64 press conferences in his brief time in office and obviously understood how important they were to the furthering of his policies. But he also enjoyed them as ritual and performance. He was a genuinely witty man, with a very Irish love of the English language, the play on words, the surprising twist. But there was an odd measure of shyness in the man, too, and that must have been at the heart of his sense of irony, along with his detachment, his fatalism, his understanding of the absurd. He was often more Harvard than Irish, but he was more Irish than even he ever thought.

We didn’t have to defend him at home, either. He did a very good job of that himself. We hurried off to watch his televised press conferences because they were such splendid displays of intelligence, humor, and style. We might disagree with Kennedy’s policies, and often did; but he expressed them on such a high level that disagreement was itself part of an intelligent process instead of the more conventional exchange of iron certitudes. He held 64 press conferences in his brief time in office and obviously understood how important they were to the furthering of his policies. But he also enjoyed them as ritual and performance. He was a genuinely witty man, with a very Irish love of the English language, the play on words, the surprising twist. But there was an odd measure of shyness in the man, too, and that must have been at the heart of his sense of irony, along with his detachment, his fatalism, his understanding of the absurd. He was often more Harvard than Irish, but he was more Irish than even he ever thought.

I loved that part of him. Loved, too, the way he honored artists and writers and musicians, inviting them to the White House for splendid dinners, insisting that Robert Frost read a poem at the inauguration. He said he enjoyed Ian Fleming’s books about James Bond; but he also brought André Malraux to the White House, and James Baldwin, Gore Vidal and Saul Bellow, along with such musicians as Pablo Casals. Perhaps this was all a political ploy, a means of getting writers and artists on his side; if so, it worked. Not many writers have felt comfortable in the White House in all the years since, not even with Bill Clinton, who truly did make the effort.

Part of Jack Kennedy’s appeal was based on another fact: He was that rare American politician, a genuine war hero. Not a general, not someone who had spent the war ordering other men to fight and die, but a man who had been out on the line himself. When he first surfaced as a national figure, at the 1956 Democratic Convention, reporters rushed to find copies of John Hersey’s New Yorker account of the PT-109 incident in the South Pacific. They read: “Kennedy took McMahon in tow again. He cut loose one end in his teeth. He swam breaststroke, pulling the helpless McMahon along on his back. It took over five hours to reach the island….”

Reading the story years after the event, some of us were stunned. Kennedy was the real article. There had been so many fakers, so many pols who were tough with their mouths and avoided the consequences of their belligerence. The type never vanishes. Over the past 20 years, the most fervent flag-wavers, particularly among the Republicans, have been men who ducked service in Vietnam, their war. I think of them, and think of Kennedy, and they all seem to be frauds. Kennedy had been there, not simply as a victim but as a hero, a man who’d saved other men’s lives. When he was president, that experience gave his words about war and peace a special authority. We also knew that his back had been terribly injured in the Solomons and had tormented him ever since. He had almost died after a 1954 operation, and he wore a brace until the day he died. But he bore his pain well; he never used it as an excuse; he didn’t retail it in exchange for votes. Hemingway, another hero of that time, had defined courage as grace under pressure. By that definition, Jack Kennedy certainly had courage.

Years later, long after the murder in Dallas and after Vietnam had fast escalated into tragedy and then disintegrated into defeat; long after a generation had taken to the streets before retreating into the Big Chill; long after the ghettos of Watts and Newark and Detroit and so many other cities had exploded into nihilistic violence; after Robert Kennedy had been killed and Martin Luther King and Malcolm X; after Woodstock and Watergate; after the Beatles had arrived, triumphed, and broken up, and after John Lennon had been murdered; after Johnson, Nixon, Ford, and Carter had given way to Ronald Reagan; after passionate liberalism faded; after the horrors of Cambodia and the anarchy of Beirut; after cocaine and AIDS had become the new plagues — after all had changed from the world we knew in 1963, I was driving alone in a rented car late one afternoon through the state of Guerrero in Mexico.

I was moving through vast, empty stretches of parched mountainous land when the right rear tire went flat. I pulled over and quickly discovered that the rental car had neither a spare nor tools. I was alone in the emptiness of Mexico, on a road in its most dangerous state. Trucks roared by, and some cars, heading for Acapulco, but nobody stopped.

Off in the distance I saw a plume of smoke coming from a small house. I started walking to the house, feeling uneasy and vulnerable. A rutted dirt road led to the front of the house. A dusty car was parked to the side. It was almost dark, and for a tense moment, I considered turning back.

And then the door opened. A beefy man stood there, looking at me in a blank way. I came closer, and he squinted and then asked me in Spanish what I wanted. I told him I had a flat fire and needed help. He considered that for a moment and then asked me if I first needed something to drink.

I glanced past him into the house. On the wall there were two pictures. One was of the Virgin of Guadalupe. The other was of Jack Kennedy. Yes, I said. Some water would be fine. ♦

This article was published in the November 1999 Irish Americans of the Century commemorative issue of Irish America.

On March 17, 1964, Robert F. Kennedy traveled to the Friendly Sons of St. Patrick in Philadelphia for his first speech since his brother John F. Kennedy was assassinated in Dallas on November 22, 1963. Chris Matthews wrote about it in his book Bobby Kennedy: A Raging Spirit and shared a Touch of the Irish with Irish America.

Thank you

A thing of beauty, Most especially to someone who knew all the players.

Hey, thanks again Pete. My eyes ain’t dry. I agree. Also remember those days & the way of events of our 3D VR in a similar way. And a brilliant, early Spring day in the city. I always found the 1st warm days of Spring as being the best time, as it brought out the best of New Yorkers. Everyone was smiling. The air was almost free of coal smoke & smog. The dirty slush of winter barely visible. And walking back to my railroad flat on 2nd St btween B&C I was smiling my Irish eyes out. I had just thrown back a few with the likes of Pete H & Jimmy B. It was 3 yrs after my last hero was killed. I was a wounded Kennedy kid with a inbred distrust of politicians and oligarchs of any kind. I was a Poet & an Artist & a drummer & a singer. I had a right hook they called Popeye. I took off my leather jacket & slung it over my shoulder. The windows & hidden art of the tenements of Alphabet City glistened in the chemical rainbow of the setting sun. My boots tapped out the cadence of the Rising of the Moon. Ah, but I was so much older then….

Pete, I am of your generation. This article has reminded me why I loved Jack Kennedy. I’m 100% Irish, I’m proud to say, or as Irish as my DNA tests showed! You took me back to my Irish Catholic mother who decided on the July 4th, 1960, that we would as a family go to the park in New Jersey where Jack Kennedy was campaigning.

I was a teenager at that point, and wasn’t really that interested in politics, so my siblings and cousins and I went to play on the park’s swings! Then in September, 1963, I entered the convent of an Irish order of nuns. One morning we were all called into our community room and were told by sobbing nuns that President Kennedy had been shot and died of his wounds. Of course, we all cried for days. And the nuns suspended all of our classes for several days and left the tv on so that we could watch all that happened afterwards. Of course we watched his funeral and suffered with Jackie Kennedy and her two little kids, who were now without a husband and father, and were homeless to boot! I totally share your love of JFK! He was imperfect, as you say, but when I look at what has happened since and most recently to the office of the President, I feel that he was such a hero to us Irish people. You have captured him perfectly, Pete! Thank you for reminding me of him in this elegant way!