All the great novels and stories of John Steinbeck slice into the American experience, clear to the bone. They are set in California, or along Route 66, where the Joads trekked across the southwest from the Dust Bowls. And Steinbeck himself, born with the century, was raised in Salinas, California, when it was still a small town on the last frontier of America.

Yet the voice of this all-American writer, he himself believed, rose from his Irish grandparents and their daughter, Olive, his mother. “I am half-Irish, the rest of my blood being watered down with German and Massachusetts English,” Steinbeck once wrote. “But Irish blood doesn’t water down very well; the strain must be very strong.”

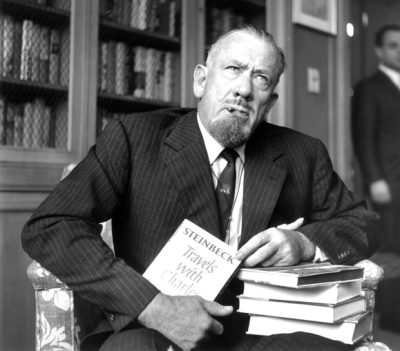

So, too, are Steinbeck’s gifts. To this day, 31 years after his death, stories by John Steinbeck are often the first great works that school children discover and embrace. Sales of his books still number in the tens of thousands annually; he is published in a dozen languages and his stories continue to be produced on stage and screen. No half-way serious list of great American writers would be complete without the 1962 Nobel Laureate in literature, the author of such American touchstones as The Grapes of Wrath, Of Mice and Men, Cannery Row, Tortilla Flat and East of Eden. And for that matter, no survey of the great Irish-American writers can bypass Steinbeck. All his life, he claimed the Irish as his own.

“I guess the people of my family thought of Ireland as a green paradise, mother of heroes, where golden people sprang full-flowered from the sod,” Steinbeck wrote in Collier’s Magazine in January 1953. “I don’t remember my mother actually telling me these things, but she must have given me such an impression of delight. Only kings and heroes came from this Holy Island, and at the very top of the glittering pyramid was our family, the Hamiltons.”

Steinbeck’s grandfather, Samuel Hamilton, left a farm near the Derry village of Ballykelly, around 1848 or 1849. “He was the son of small farmers, neither rich nor poor, who had lived on one land hold and in one stone house for many hundreds of years,” Steinbeck wrote in East of Eden. The reason for Samuel’s emigration was a mystery. “There was a whisper — not even a rumor but rather an unsaid feeling — in my family that it was love drove him out, and not love of the wife he married. But whether it was too successful love or whether he left in pique at an unsuccessful love, I do not know. We always preferred to think it was the former.”

In New York, Samuel met and married Elizabeth Fagen, the daughter of Irish immigrants. They sailed to California and homesteaded a ranch of poor land in the Salinas Valley. “My grandfather, who had come from [Ireland] carrying the sacred name, was really a great man, a man of sweet speech and sweet courtesy…. His little bog-trotting wife, I am told, put out milk for the leprechauns in the hills behind King City, California, and when a groundling neighbor suggested the cats drank it, she gave that neighbor a look that burned off his nose,” Steinbeck wrote in Collier’s.

Among the nine Hamilton children was Olive, who left home to become a school teacher, a journey regarded in that time as “an honor, a bit like having a priest in the family in Ireland,” the Steinbeck biographer Jackson Benson writes in The True Adventures of John Steinbeck, Writer.

Olive Hamilton would marry John Ernst Steinbeck, and they had three daughters and one son. John Steinbeck was born in 1902. He and his sisters spent summers on the Hamilton ranch, and listened by night to the tales of fairies and enchanted forests told by their Irish mother.

Irish blood doesn’t water down very well; the strain must be very strong.”

On his way to the pantheon, Steinbeck lived in stone-soup poverty for nearly 20 years before he enjoyed his first taste of financial security, with the publication of Tortilla Flat and In Dubious Battle, then with Of Mice and Men and The Grapes of Wrath, for which he won the Pulitzer Prize in fiction.

By the late 1940s, though, his work and fame were firmly staked. In 1947, his friends Burgess Meredith and Paulette Goddard suggested he write a play for Dublin’s Abbey Theatre about a modern Joan of Arc persecuted for warning against atomic warfare. “The idea appealed very much to Steinbeck’s pride in his Irish background and his interest in Irish mysticism,” writes Benson. “He was also excited about doing a play for the Abbey Theatre, the scene of so much controversy and theatrical ferment, and an Irish audience. It was a connection he longed to make, for he still felt, as he would tell an interviewer that spring, that his gift for writing was based on his sensitivity to sound, a gift, of course, that he believed came to him through his mother’s family.” That project fell apart with the collapse of his second marriage.

As a correspondent in World War II, Steinbeck frequently landed in Ireland, but never quite set himself towards Derry. Married happily to his third and final wife, Elaine, they at long last visited in 1952. The trip was such a catastrophe that it became one of his best pieces of journalism, “I Go Back to Ireland,” published in Collier’s. The Steinbecks found Derry a bleak city, the hotel where they stayed uniquely short of the barest hospitality. They had arrived two minutes late for dinner, and could not beg a morsel; they were not allowed a drink or a sandwich in their room; they could not arrange a morning newspaper. No one would take a bribe.

More to the point, when they drove out to Ballykelly and to the farmland called Mulkeraugh, the last of the Hamiltons had been dead for two years. Her name was Elizabeth, and she had grown strange, the neighbors told John, calling out to the dead brother who shared their bachelor quarters. Another strangeness, the neighbors told Steinbeck, was that she had found a “cause” in her final days. She decreed that all her property be sold at her death to fund a political party that would resist joining Ulster with Eire.

Years later, the Steinbecks would return to Ireland as guests of the director John Huston at St. Clerans, his estate in Galway. They wandered through the countryside. “The west country isn’t left behind — it’s rather as though it ran concurrently but in a nonparallel time,” Steinbeck wrote in a letter in 1965. “I feel that I would like to go back there. It has a haunting kind of recognition.”

Beyond the clear lines of genealogy, the hard facts of trips, there is the sensibility of a man who cherished the land, saw magic in places, and gazed without blinking at the brutality that closes the circle of farm life — much like Seamus Heaney, another son of Derry. Heaney writes: “Running water never disappoints.”

And so it is for the young boy in “The Red Pony,” the first great story by Steinbeck, set on the dry, dusty ranch of the Hamiltons, half a world away from Derry: “Jody traveled often to the brush line behind the house. A rusty iron pipe ran a thin stream of spring water into an old green tub. Where the water spilled over and sank into the ground there was a patch of perpetually green grass. Even when the hills were brown and baked in the summer that little patch was green. The water whined softly into the trough all the year round.”

Editor’s Note: This article was originally published in the November 1999 issue of Irish America. ⬥

Leave a Reply