On the 30th anniversary of the 1969 deployment of British troops in Northern Ireland, Brian Dooley looks back on the response both in Ireland and in Irish America.

About 5 p.m. on Thursday, August 14, 1969, British soldiers of the Prince of Wales Own Regiment swung into Derry’s William Street and began stretching barbed wire across the road, so ending the Battle of the Bogside.

The police were in retreat, the Catholic Bogsiders jubilant and relieved after several days’ fighting to defend their neighborhood from the Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC). Local civil rights leader Eamonn McCann and Nationalist MP Eddie McAteer approached the soldiers, who were part of a permanent 2000-strong British Army garrison stationed in Northern Ireland, but the first to be ordered onto the streets for active duty.

“No one knew their intentions and we didn’t know if they were going to move into the area,” McCann told Irish America. “We spoke to the commanding officer over the barbed wire and he said, `We’re not going to come into the Bogside.’ There would’ve been a riot if they’d tried to come in.”

Many Bogsiders regarded the soldiers in their World War II-style uniforms and helmets as saviors who had charged in to save them from possible massacre by the police and their auxiliaries.

The conflict between the RUC and the Bogsiders looked so serious that Irish Taioseach [Prime Minister] Jack Lynch had gone on TV late the previous night to warn that the Irish government would not stand idly by. He also asked that a United Nations peacekeeping force be dispatched to maintain order and announced that field hospitals would be set up on the Irish border.

Riots ravaged Belfast that week too, and local MP Gerry Fitt telephoned British Home Secretary James Callaghan to ask that British troops be sent to protect Catholic areas of the city. British soldiers appeared on the streets of Belfast the day after they entered Derry.

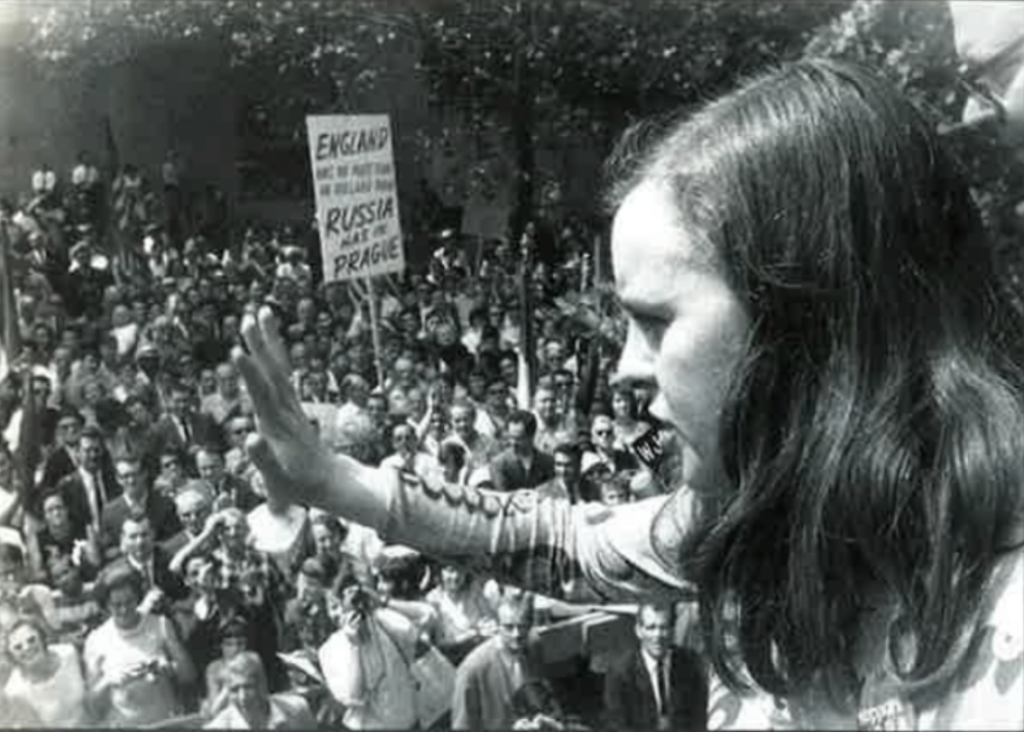

While many Catholics welcomed the soldiers, others regarded their presence with suspicion. Civil rights leaders and MP Bernadette Devlin, who had fought in the Battle of the Bogside, predicted that the troops were there not to liberate the Catholics but to repress them.

British troops on the streets of Belfast and Derry also provoked a mixed response from Irish America, and widened the splits between various Irish American groups supporting the Northern Ireland civil rights movement.

In the months leading up to August 14, the largest of these Irish American groups — the American Congress for Irish Freedom (ACIF) — had been lobbying the U.S. government to intervene in Northern Ireland. In March 1969 ACIF leader James Heaney arranged for nationalist politicians Gerry Fitt and Austin Currie to speak in New York and to meet Senator Ted Kennedy and Hubert Humphrey.

A month later Heaney met with State Department officials to press the Nixon administration to denounce anti-Catholic discrimination in Northern Ireland, and in June 1969 he organized over 100 Members of Congress to write to the President attacking the intolerance “encouraged by and rooted in the laws of Northern Ireland.”

The Nixon administration’s dismissal of the problems in Northern Ireland as an internal matter for Britain did not deter the ACIF or its left-wing counterpart, the National Association for Irish Justice (NAIJ), or other Irish American organizations from agitating vociferously in the weeks leading up to August 14. One group — the United Ireland Committee — even placed an ad in the New York Times on May 16 to recruit volunteers to fight alongside Catholics in Northern Ireland.

But the organizations were sharply divided about how best to support civil rights in Northern Ireland. In January 1969 moderate Derry civil rights leader John Hume had addressed a 1,000-strong citizens’ army in the Bogside, urging them to defend the area and allow no one in, and many Americans wanted to send money for weapons to protect Catholic neighborhoods.

Others like NAIJ co-founder Seamus Naughton tried to keep the focus away from supplying guns and on civil rights issues. “We were trying to organize second and third generation Irish in America who still saw the problem as a religious one, simply in terms of Catholic and Protestant, and of course the British were trying to make it look like that, like a primitive conflict,” he told Irish America.

“We were discussing issues of democracy in Ireland to show it was a socioeconomic problem but it turned some people off. ACIF didn’t want to deal with the issues around civil rights, but it had a romantic pull for people who wanted an easy answer like `England Get Out of Ireland’ or `Freedom for Ireland,'” he said.

Brian Heron, grandson of 1916 Easter Rising leader and martyr James Connolly, headed the NAIJ, and the organization was the official affiliate of the Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association (NICRA).

The split between ACIF and NAIJ mirrored fractures within the Northern Ireland civil rights movement, with the leftist students organized around People’s Democracy in conflict with some of the older elements in NICRA.

Some Irish Americans were critical of the NAIJ’s association with the U.S. civil rights movement and its ties to Cesar Chavez’s campaign to organize farm workers. Organizers of the 1969 New York St. Patrick’s Day parade refused to allow the NAIJ to take part because it was too political.

By mid-August, tensions between ACIF and NAIJ had reached breaking point, and were exacerbated by Bernadette Devlin’s arrival in the U.S. A few days after August 14, she was spirited out of the Bogside in a speeding car following an ambulance and then flown across the Atlantic. “I was sent to America to get me out of Derry because I opposed the acceptance of the British Army,” she said. “In some way I still don’t know, the [Irish] Free State Army or government or somebody [arranged it]. I did not have a passport, never mind a friggin’ visa.”

Although a huge hit in the U.S. with the media (she appeared on the Johnny Carson Show and Meet the Press and was featured in virtually every major newspaper), her visit antagonized conservative elements in ACIF and widened the rift between the various Irish American organizations.

On August 21, Mayor John Lindsay of New York presented her with the keys of the city which she later turned over to the local Black Panther Party in a gesture interpreted by the Panthers as one of solidarity but by many Irish Americans as one of contempt. In Detroit a few days later, she refused to speak at a rally organized by Irish groups at Ford Hall until blacks who had been refused admission were allowed in.

In Philadelphia some of the audience who had come to hear her speak left in protest when she sang “We Shall Overcome” with a black singer, and she angered many West Coast Irish Americans by insisting on visiting Operation Bootstrap, a ghetto renewal scheme in Watts. By the time she addressed a crowd in Chicago and told Irish Americans who were opposed to civil rights in the U.S. they were guilty of the same oppression as Orangemen in Northern Ireland, her popularity in conservative Irish America was finished, and the split between left and right Irish American organizations complete.

In the following months, both the ACIF and the NAIJ collapsed after a surge in violence in Northern Ireland brought about a new political reality, although in November 1969 an NAIJ conference in New York bolstered the organization’s radical credentials. One of the prominent guests was Northern Ireland civil rights activist Eilis McDermott, who was inducted by the local Black Panther Party in the city as an honorary Panther during her visit.

And guest of honor was IRA Chief Cathal Goulding, whose attempts to mould the IRA into a leftist revolutionary movement led, within a few weeks, to a split and the formation of the Provisionals.

By April 1970 the split in the republican movement in Ireland was sealed, and many in ACIF drifted off to join the newly formed Irish Northern Aid Committee (Noraid), which collected money to support the families of Provisional IRA prisoners.

The NAIJ collapsed by the end of 1970, although some activists based around New York formed the National Association for Irish Freedom (NAIF), which emphasized its support for socialism in Ireland and attracted support from black U.S. civil rights luminaries Rev. Ralph Abernathy and comedian Dick Gregory.

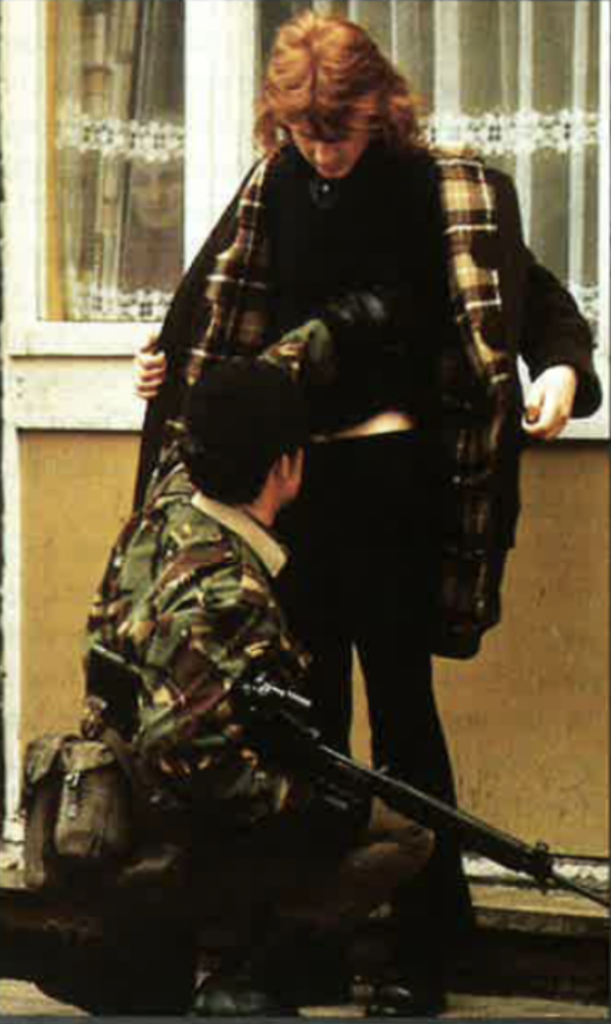

Back in Northern Ireland, the honeymoon period for British soldiers in Catholic neighborhoods proved brief. When Gerry Fitt called Callaghan and asked for troops to be sent, the British Home Secretary said, “I can get the army in but it’s going to be a devil of a job to get it out,” and so it proved. The popularity of the Prince of Wales Own Regiment lasted for the few weeks the British army allowed Bogsiders to police themselves, but when it became clear that the army presence was not a temporary measure their appeal quickly faded.

Any residual affection for the army rapidly evaporated after December 1969, when the Gloucestershire Regiment, who swiftly earned a reputation for heavy-handedness and harassment in its dealings with civilians, replaced the Prince of Wales Own soldiers.

In Belfast disillusionment with the British troops also set in within months. The 600 soldiers of the Third Battalion Light Infantry who had marched into the city with fixed bayonets on August 15 enjoyed the enthusiastic welcome their colleagues had been given in Derry the day before, but by April 1970 British soldiers were in conflict with young rioters in Ballymurphy. Three months later a 36-hour curfew imposed on the Catholic Falls Road area did little to improve military-civilian relations.

The British army that went into Northern Ireland 30 years ago had little idea of how to handle the fragile political situation but it did have some experience of colonial conflicts. The commander of the British troops in Derry, Brigadier Peter Leng, had been an officer in Aden between 1964 and 1966. Other soldiers had seen duty in Oman, Cyprus or Kenya.

The counter-insurgency methods learnt in the tropics of the Empire translated poorly to the streets of Derry and Belfast. The introduction of internment without trial in August 1971, and the shooting of 13 unarmed civil rights marchers by British soldiers in Derry on Bloody Sunday in January 1972, persuaded many Catholics to regard British soldiers as an enemy force of occupation.

The Prince of Wales Own Regiment was reinforced by thousands more soldiers in the following years, reaching a peak of over 20,000 British troops in Northern Ireland in 1972. By 1980 that number had halved, and hovered at around 10,000 for the next decade.

By the early ’90s cuts in the British Army budget at the end of the Cold War meant troops could not be so easily rotated in from their barracks in Germany, and resulted in longer tours of duty and further troop reductions.

Since last year’s Good Friday Agreement, some areas in Tyrone and south Armagh have seen an increase in British troop presence, but soldiers no longer roam the Bogside with the same regularity they once did. Military convoys occasionally drive down William Street, where the first soldiers appeared 30 years ago, but foot patrols “are not common any more,” said Eamonn McCann. “British soldiers tend to stay out of sight now.”

Editor’s Note: This article was originally published in the August / September 1999 issue of Irish America. ⬥

Leave a Reply