When I was a little girl visiting Ireland for the first time, my grandparents’ farm in County Mayo was right in the shadow of Croagh Patrick — in fact, you could see the mountain from the kitchen window.

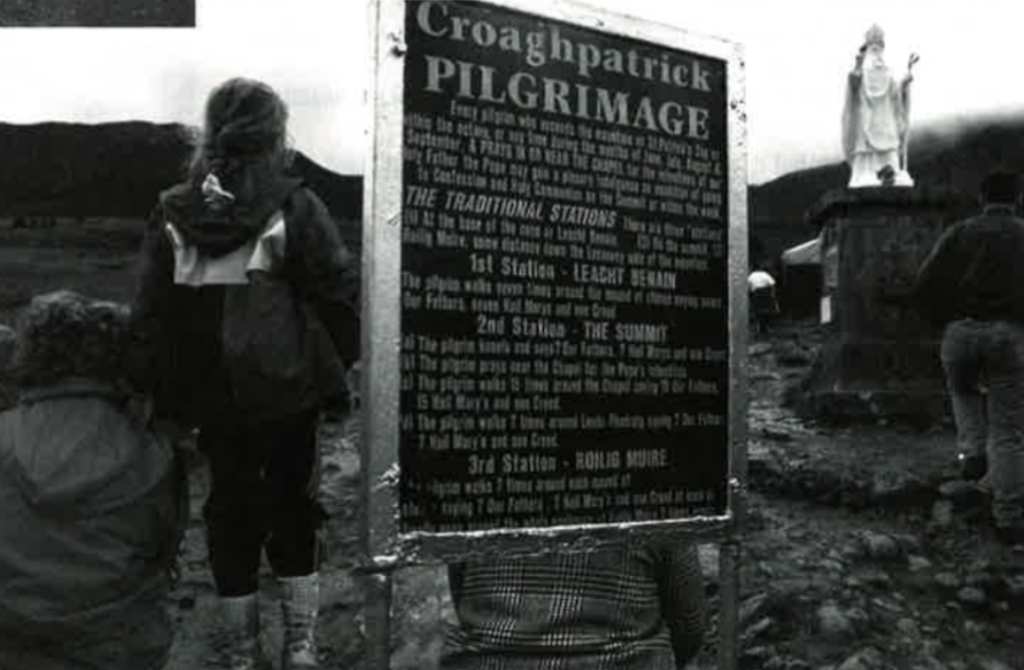

Though just 2,510 feet, it loomed in the fog and mist like Ireland’s own Everest. I remember being told that Croagh Patrick, called the “reek” by locals, was a holy mountain and that people climbed to the tiny white chapel on the summit and that sometimes they did it barefoot and that sometimes their feet would bleed. When my mother and older sister Siobhan set off one day to climb it, I cried — convinced that they were going to fall off and never be seen again.

I’ve been back to Ireland several times since then, always staying near the mountain which is located in the village of Murrisk. Every time I saw it, I marveled at its sheer beauty, set among fields and bogs and at the lapping edge of Clew Bay. But because I was never able to dispel the image of bloodied pilgrims from my mind, I had never really considered climbing it. And so, when I returned last August with my brothers Patrick and Tom, Tom’s girlfriend Julie and my cousin Fergus I felt no differently. But fate has a way of intervening. We happened to be staying in a lovely bed-and-breakfast called Bertra House, literally across the road from Croagh Patrick, and, no matter how much I tried to ignore it, the mountain seemed to be beckoning.

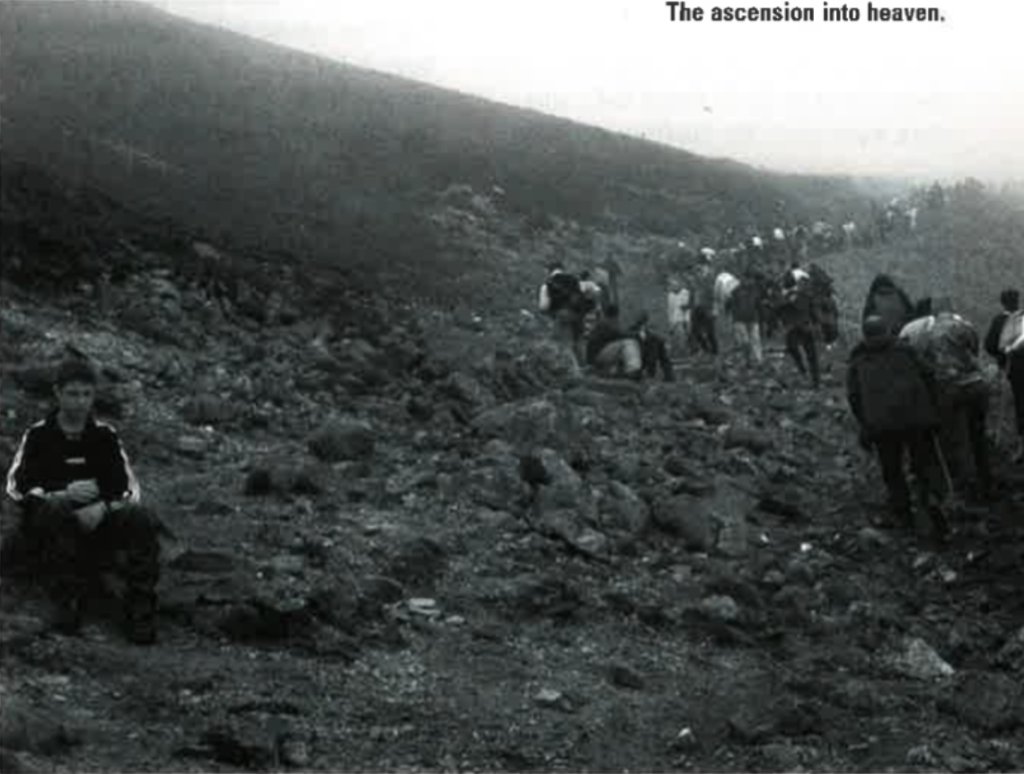

The rest of the group was keen on making the trek. We listened to the weather reports and heard that the following day (a Tuesday) was the only one expected to be clear for the next week. That night I prayed for rain. Naturally, it was a gorgeous, sunny day. I’ve never seen four people more chipper at eight in the morning. Tom and Julie were putting on their hiking boots and baseball caps; Patrick was busy packing his knapsack. I couldn’t back out now. As we pulled in to the car park at the base and saw the steady stream of people inching their way up, looking like so many ants, I have to admit, I started getting a little excited.

This was, after all, a mountain steeped in lore. The legend has it that in 441 A.D., St. Patrick fasted for forty days and nights on the summit, eventually driving out all the serpents from the land by tossing his bell at them and banishing them in the hollow known as Lag na nDeamha on the north side of the mountain. There are several stations along the well-signposted route where you can say penance, and the annual pilgrimage called “Reek Sunday” is held on the last Sunday of July.

Thousands of people, tourist and pilgrims alike, from all over the world make the journey and many still do it barefoot, though I didn’t see any the day I climbed (thankfully). The stony slopes are, in fact, extremely slippery and in inclement weather can be quite dangerous. Each year there are injuries and even deaths.

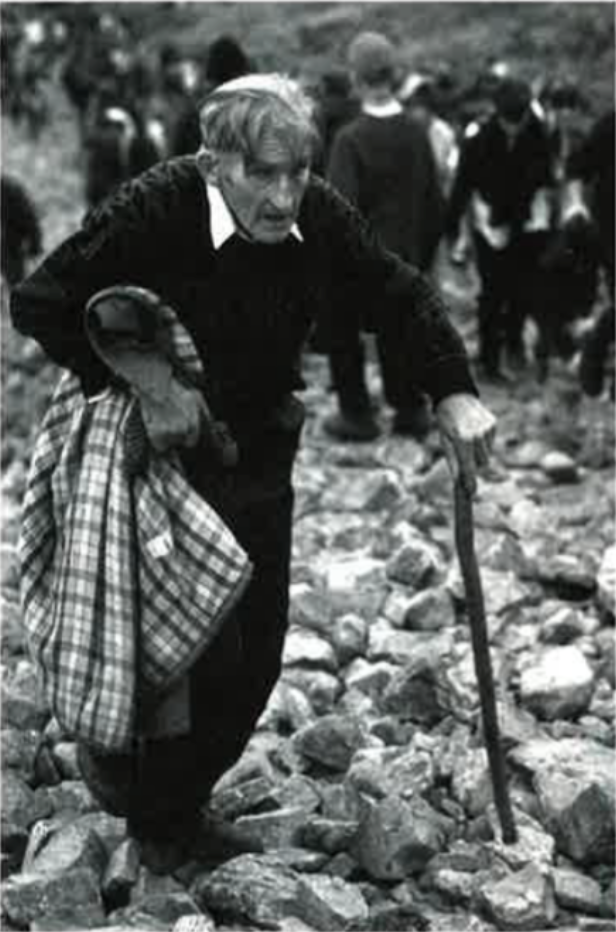

At the start of the trail a stout old man was selling walking sticks for a pound. “You won t need them going up, but you’ll need them coming down,” he told us matter-of-factly. From what we could see the first part of the trail looked easy-going. It was relatively flat, though certainly rocky. The higher we went, the more glorious the views became. We could clearly make out the fields and farms below, and in the distance Clew Bay glistened in the sunlight. We stopped a few times for water and photos. I was feeling good.

There are a few tricky bits in the middle as it gets steeper, and as you get higher the wind picks up and the mist starts rolling in. My thighs were starting to ache, but onward I went. When the trail led to a straight vertical line up, with large loose rocks everywhere, I freaked a bit. Could I do it? I looked around and saw kids as young as 10 and adults at least in their sixties. There was life in the old girl yet. At the sharpest incline, you find yourself practically crawling, Spider-Man-like. My face was beet red and I was huffing and puffing, as the wind howled and things below got very tiny indeed. I looked at Tom and Fergus and they were in the same predicament. I realized at this point that everyone was on their own. There were no friendly hands helping anyone. As we slowly ascended, we passed people descending. It was a narrow passage and you have to keep out of people’ s way, lest someone slide and knock into you and send you back down in the parking lot in a heap. A few of them looked hapless and helpless, afraid to take a step for fear of slipping. One woman simply sat on her rear, too terrified to move. I could only concentrate on the rocks directly in front of me. As I passed her, our eyes briefly met. She could do nothing for me and I could do nothing for her. Love to help ya lady, I thought, but I got my own problems!

Onward and upward. Must keep going. My legs were throbbing with each step and I was still a ways from the summit but at least it was in my sight line, so I soldiered on. Patrick, with his 6’4″ frame and long legs, made it up first. Finally, finally, I made it to the top! I was dead last, but I didn’t care. I joined the “elite” group of about forty climbers, each looking triumphant. The sun flickered in and out of the clouds; the wind howled wickedly. I don’t care how small a mountain it is, it was a tough climb (it took about an hour and a half). The 360 degree views were incredible, though on the south side the clouds looked ominous. The fog and mist made it almost ethereal. We sat on the stairs of the chapel (it’s only opened on Reek Sunday though visiting priests are also given keys) and took a well-earned rest. Julie came through with Cadbury chocolate bars but we couldn’t help notice that all the Germans practically had three-course meals spread out before them.

We tried to spot our farm in the village called Mullagh off to the west but the fog was too thick and getting worse. So we decided to head back down, which believe me, is no picnic either. In fact, it’s more arduous than going up. I certainly was glad to have that stick with me. I fell a few times but eventually I perfected a side slide-and-glide foot maneuver that got me through the worst of it and the rest of the way down was manageable.

On the flatter portion, we passed a group of Italians making their way up without the coveted sticks. We were tempted to give them ours but decided we’d rather keep them as souvenirs. And even though the terrain was more manageable, you’re so happy to be near the bottom that your mind wanders. You start thinking about that huge lunch that you’ve earned and not about taking slow steps on solid ground rather than on loose stones, so little slips (quite embarrassing at this late stage) do occur. As the car park became more of a reality to us, we all began to breathe sighs of relief, especially since the sun had all but disappeared. Time to eat.

We hooked up with our uncle Sean at a local pub, Staunton’s in nearby Lecanvey and over soup and sandwiches poured out every endless detail. Since Sean grew up just minutes from the mountain he knew every inch of it, even the original route called Tochar Phadraig (Patrick’s Causeway) which begins at Ballintubber Abbey. He laughed at us for using walking sticks (and for paying a pound no less!) and told us stories of when he was just a mere lad hauling soda on the back of a donkey up to the summit to sell to thirst-quenched tourists, who’d pay just about anything for an ice-cold drink. It didn’t sound like an easy business venture, but it was a lucrative one he assured us with a wink.

That evening was, needless to say, pretty tame. We compared bruises and rehashed our war stories. It truly was an awesome feeling to have finally conquered Croagh Patrick. And, being an Irish-American, I felt it was my duty to finally climb the thing. They say if you make it to the top, you’re supposed to say a prayer and I’ll admit I did say a wind-swept prayer up there behind the chapel. Of course, I can’t tell you what it was but one thing I will tell you is that it wasn’t to climb Croagh Patrick again. Once is enough for me.

Editor’s Note: This article was originally published in the August / September 1999 issue of Irish America. ⬥

Leave a Reply