O ne Saturday afternoon in March 1960, when I was twelve years old, I did my bit to help build the Kennedy legend. I went door-to-door in my Milwaukee suburb of Wauwatosa, distributing the Reader’s Digest condensed version of Survival, John Hersey’s 1944 New Yorker article about the PT 109 incident. I didn’t know at the time that Hersey’s account put a highly romanticized spin on John F. Kennedy’s record in World War II, or that selling Kennedy as a war hero via that article had been a staple of his political campaigns since he first ran for Congress in 1946. At the time of the 1960 Wisconsin presidential primary, I was just a naive, starstruck kid excited by the possibility of a fellow Irish Catholic rising to the highest office in the land.

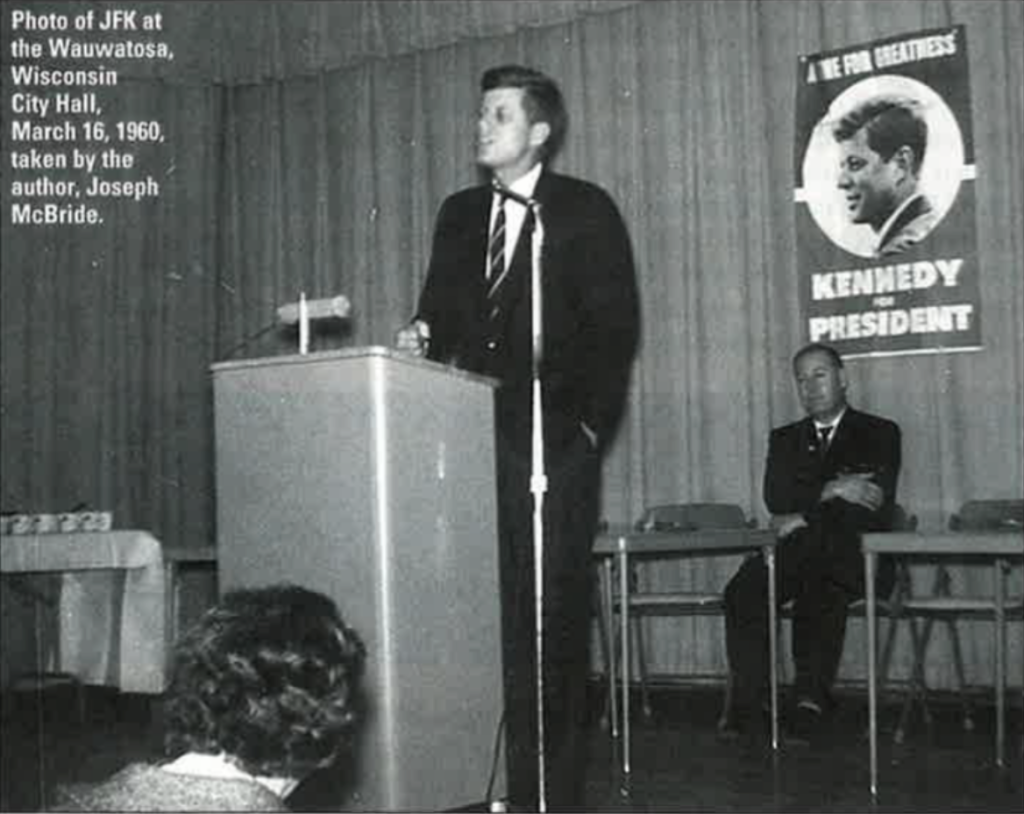

The day Kennedy was elected president, my father, Raymond McBride, borrowed my 1928 “Al Smith for President” button and wore it to work at the Milwaukee Journal as a witty reminder of how far Irish Catholics had come in American national life. I was fortunate to have the opportunity of meeting JFK on three occasions in 1960 and 1962 because my mother, Marian, was vice-chairman of the Wisconsin Democratic Party. At the “Kids for Kennedy” rally she staged on March 16, 1960, at the Wauwatosa City Hall, I answered a question Kennedy asked the audience about American history, drawn from his book Profiles in Courage, which I luckily had just read. “I hope I don’t have to run against you in 1964,” he quipped, hitting me with the full dazzling impact of the Kennedy charm.

On the night of April 2, three days before the primary election between Kennedy and Minnesota Senator Hubert H. Humphrey, I attended a Kennedy rally at Milwaukee’s South Side Armory. Since the rally was held in a Polish neighborhood, Jacqueline Kennedy addressed the crowd with a few words in that language, captivating them with the talent for linguistics she would use to such great advantage as First Lady. Members of JFK’s PT 109 crew were there that night, along with Robert Kennedy and Eunice Kennedy Shriver, who said when we were introduced, “I wish it were me running for president.” But in that generation of the Kennedy family, girls were not raised for such lofty ambitions.

I didn’t realize then that we were all helping to make cinematic history as well as political history. For that rally served as the memorable final sequence in the 1960 documentary Primary, one of the first important works of the cinéma vérité movement in American documentary filmmaking. Primary was directed by Robert Drew, assisted by cameramen Richard Leacock and D. A. Pennebaker, who captured many revealing images, such as a close-up of Jackie’s white-gloved hands twisting nervously behind her back as she gave the speech.

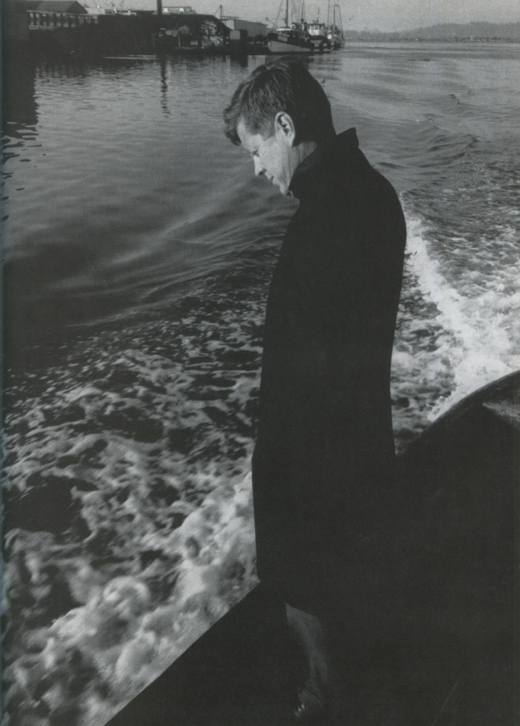

Beginning in the bleak, deserted snowscapes of northern Wisconsin, where few people paid much attention to the candidate from Boston, Primary chronicles the step-by-step creation of our first movie-star president, showing Midwesterners gradually beginning to respond to the offhand, ironic charm of this exotic Boston Irishman and Kennedy drawing confidence from their enthusiasm. The final rally shows his full apotheosis into superstardom, like Frank Sinatra before him or the Beatles just after his death. Caught up in that frenzy, I managed to get the future president to autograph my wrist. Then I stuck my Brownie camera about three feet from his face and fired off a flashbulb to take a closeup (reproduced on the opposite page). Though somewhat startled, the candidate graciously responded with amusement rather than irritation.

Primary inaugurated a cottage industry that continues unabated today, a virtual genre of Kennedy movies and TV shows, both documentaries and fictionalized sagas. The Kennedys have had nearly every aspect of their lives portrayed on the big and small screens, from Joe Sr.’s affair with Gloria Swanson and Joe Jr.’s death in World War II to Jack’s assassination, Jackie’s marriage to her Greek Tycoon, and even John Jr.’ s encounter with a fictional Irish-American woman named Murphy Brown. We have seen everything from the vapid 1963 biopic PT 109 (produced, I’m sorry to say, by my great-uncle Bryan Foy) to JFK, The Missiles of October, The Kennedys of Massachusetts, Hoover vs. the Kennedys: The Second Civil War, The Ted Kennedy Jr. Story, and Joshua Seftel’s acerbic 1996 TV documentary about Patrick Kennedy running for Congress in Rhode Island, Taking on the Kennedys.

Norman Mailer, as so often happens, was onto the meaning of the phenomenon of Kennedy’s stardom long before anyone else. In his famous Esquire article about the 1960 Democratic convention, Superman Comes to the Supermarket, he wrote that with John Kennedy’s election, “America’s politics would now be also America’s favorite movie, America’s first soap opera, America’s best-seller…He was like an actor who had been cast as the candidate, a good actor, but not a great one — you were aware all the time that the role was one thing and the man another — they did not coincide, the actor seemed a touch too aloof (as, let us say, Gregory Peck is usually too aloof) to become the part. Yet one had little sense of whether to value this elusiveness, or to beware of it. One could be witnessing the fortitude of a superior sensitivity or the detachment of a man who was not quite real to himself.”

The Kennedys pioneered the concept of politics as show business, a development that has utterly transformed the business of governing. This shouldn’t have come as a total surprise, since their father had run a Hollywood studio. When Joe Kennedy headed the distribution and production company Film Booking Offices of America (FBO) from 1926-28, he relied upon his sons Joe Jr. and Jack for advice on hiring film stars, notably their football hero Red Grange. To lend more prestige to himself and to the movie business, Joe Sr. sponsored one of the first academic seminars on film, bringing producers and studio executives to the Harvard Business School for discussions he assembled into the first of many Kennedy books, The Story of the Films (1927).

Emulating his swashbuckling old man, JFK cut a famously wide swath through Hollywood in his young manhood (and beyond). His list of glamorous conquests ranged from well-documented liaisons with Gene Tierney and Marilyn Monroe to rumored encounters with many other female stars. JFK friend and fellow playboy Robert Stack wrote in his autobiography, “I’ve known many of the great Hollywood stars, and only a very few of them seemed to hold the attraction for women that JFK did, even before he entered the political arena. He’d just look at them and they’d tumble. I often wondered (in subsequent years) why he wasted his time on politics when he could have made it big in an important business like motion pictures.”

Kennedy, of course, was not the first politician to parlay personal charisma into power. Franklin D. Roosevelt masterfully used his ‘fireside chats’ on radio and his newsreel appearances to talk directly to the American people. Homely though he was, Abraham Lincoln must have shown plenty of star quality in the debates with Stephen Douglas that vaulted him into the White House. But Lincoln and FDR lacked one advantage JFK had: television.

It’s no accident that Kennedy’s rise to national prominence coincided with the advent of TV as the nation’s leading news and entertainment medium. As Primary and his 1960 campaign commercials demonstrate, the Kennedys from the beginning cannily packaged and sold his beguiling image. The first Kennedy-Nixon debate (directed by Don Hewitt, who later became the executive producer of 60 Minutes) is credited with winning JFK the election. His presidential press conferences, with their self-deprecating humor and sophisticated repartee, brought him regularly into American homes, making him seem a beloved member of the family; the best moments of his press conferences are excerpted in the documentary Thank You, Mr. President. Many Americans also enjoyed the 1962 comedy album “The First Family,” featuring impressionist Vaughn Meader, whose own career would be shattered by the president’s assassination. JFK dryly remarked about the album, “I thought it sounded more like Teddy than it did me.”

Kennedy’s masterful command of television was matched by his wife in her 1962 CBS special A Tour of the White House with Mrs. John F. Kennedy (directed by Franklin Schaffner), in which the president makes a lighthearted appearance. JFK further promoted himself in such TV documentaries as The Making of the President 1960, which borrowed liberally from Primary, and Drew’s Crisis (1963), about the Kennedy brothers’ showdown with Governor George Wallace over the integration of the University of Alabama (condensations of Primary and Crisis are included in Drew’s later documentary Being with John F. Kennedy.)

One of the most poignant of all Kennedy documentaries, Darragh Byrne’s John F. Kennedy in the Island of Dreams, was made in 1993 for Radio Telefis Eireann. Including Irish film and TV footage of the president’s joyous and nostalgic visit to his ancestral homeland in June 1963, as well as interviews with people who were there, it is available on videotape in the U.S. from White Star as JFK in Ireland The program begins with Kennedy’s now-heartbreaking words of farewell to the crowd in Galway’s Eyre Square, “So I must say that though other days may not be so bright, as we look toward the future, that the brightest days will continue to be those in which we visited you here in Ireland.”

Television can be a double-edged sword, merciless in its ability to expose sham and pretension. I remember watching Rose Kennedy doing a live TV interview during her son’s presidency. At first, she talked about political matters in a gruff, hardboiled old pol’s voice that seemed to jar with her matriarchal public image. Suddenly realizing she was on the air, Rose almost instantly transformed herself into the softer character with whom we were all familiar. I’ve never seen that clip rerun anywhere since. Teddy Kennedy was more unlucky when, during his campaign for president in 1980, he was unable to tell Roger Mudd on camera why he wanted the job. That clip was endlessly replayed, destroying his candidacy.

Even JFK had his own media misfire with the premature and excessively reverent PT 109, which he sank with his own meddling. JFK’s first choice for the role was Warren Beatty — the president recognized a kindred rakish spirit — but Beatty wisely turned it down. Cliff Robertson’s sole attempt at characterizing JFK was to constantly break into a foolish grin. Hollywood was scandalized by Beatty’s supposed arrogance in saying no to the wishes of the commander-in-chief, but JFK told him, “You sure made the right decision on that one.”

Kennedy’s murder in Dallas on November 22, 1963, is the most photographed political assassination in history. The many photographers (mostly amateurs) who captured the event, or parts of it, in motion pictures and stills have helped to make this, in Mailer’s phrase, “The Great American Mystery.” Amateur filmmaker Abraham Zapruder showed remarkable instinct in picking the almost ideal spot to document the assassination. Without his seminal 8mm film’s visual evidence refuting the Warren Commission’s single-bullet theory, most of the public today might actually believe the myth that Kennedy was killed by a lone gunman.

Some of the film taken during the motorcade is missing, including 16mm film shot from a camera car by Tom Craven of CBS-TV, 8mm footage taken by Kennedy aide Dave Powers from the Secret Service car directly behind the president, and possibly a film shot from the Grassy Knoll by a young soldier named Gordon Arnold. But the Holy Grail of assassination researchers is the never-seen film by the “Babushka Lady,” who was shooting on the opposite side of the street from Zapmder, with a close view of Kennedy and a clear view of the Grassy Knoll. The most complete and revealing filmed records presently available of the assassination are Robert Groden’s videotape compilations JFK: The Case for Conspiracy and The Assassination Films. The best pictorial compilation books on the subject are Groden’s The Killing of a President and Richard B. Trask’s Pictures of the Pain: Photography and the Assassination of President Kennedy.

If Kennedy were still with us, he could take pride in the fact that Oliver Stone’s controversial 1991 film JFK proved far more potent at the box office than the filmmaker’s Nixon, despite the attacks on Stone’s largely accurate recreation of the assassination by Dan Rather and many others in the media anxious to cover up the shortcomings of their own coverage of the original event. Other full-length treatments of the assassination range from the documentaries Four Days in November, Rush to Judgment, and The Men Who Killed Kennedy to the clumsy but intermittently involving 1973 docudrama Executive Action and the deplorably falsified subgenre of films and TV movies about those enigmatic figures Lee Harvey Oswald and Jack Ruby. Avant-garde filmmaker Brace Conner provocatively drew comparisons between the assassination and bullfighting in his once-controversial short film Report (1965).

Some of the best films on the subject have been fictionalized treatments seeking deeper truth, notably Seven Days in May (the 1964 film about a political coup, filmed partly at the White House in 1963 with Kennedy’s approval), Blowup, The Parallax View, Winter Kills, The Package, and In the Line of Fire. It’s eerie to realize that the first fictionalized account of the Kennedy assassination may have starred JFK himself. During his presidency, he reportedly made a home movie in which he jokingly enacted his own killing. That film has never seen the light of day. Perhaps that bizarre escapade was in part a reflection of Kennedy’s fascination with James Bond. The president’s widely publicized consumption of Bond novels helped popularize Ian Fleming’s character, although I’ve always found it disturbing that what Kennedy was promoting was a series of books and films glorifying an assassin in the employ of the British Secret Service.

The stunning 1962 film version of Richard Condon’s The Manchurian Candidate, which seemed to eerily prophesy the events in Dallas, was subsequently withdrawn for many years. In another odd footnote, the director of both that film and Seven Days in May, John Frankenheimer, drove Robert Kennedy to the Ambassador Hotel in Los Angeles on the day of his assassination in June 1968. Befitting his kid-brother status, Bobby’s life has seldom been dramatized (a notable exception is the 1985 miniseries Robert Kennedy and His Times, starting Brad Davis), and Bobby failed to persuade Twentieth Century-Fox to film his book about his crusade against the mob, The Enemy Within, reportedly because the Teamsters Union made more persuasive arguments in opposition. Charles Guggenheim won an Oscar for his 1968 documentary short Robert Kennedy Remembered, but Barbara Frank’s beautifully filmed color documentary feature about RFK’s California race, The Last Campaign, inexplicably has never found a distributor. There’s also an incisive but little-seen 1975 documentary about RFK’s shooting, The Second Gun.

I confess to a general antipathy to dramatized portrayals of members of the Kennedy family, perhaps because they almost always seem so inferior to the genuine articles. JFK is usually played by a second-rate “star” such as James Franciscus, Peter Strauss, or Stephen Collins. One of the best portrayals of a Kennedy on screen is Michael Parks’ Bobby in another virtually unknown film, Larry Cohen’s darkly revisionist 1977 take on modern American history, The Private Files of J. Edgar Hoover. Parks’s portrayal is so moving because he does not attempt a simplistic impersonation, unlike most of the actors in such TV movies or miniseries as The Kennedys of Massachusetts, JFK: Reckless Youth, Jacqueline Bouvier Kennedy, and A Woman Named Jackie. Nevertheless, Blair Brown gave a thoughtful and touching interpretation of Jackie in the 1983 miniseries Kennedy, opposite Martin Sheen.

By far the best Kennedy TV movie to date is The Missiles of October. Filmed in 1974, this gripping drama by Stanley R. Greenberg, based on Robert Kennedy’s book Thirteen Days: A Memoir of the Cuban Missile Crisis, succeeds precisely because it was not made in a naturalistic manner. The theatrical settings and director Anthony Page’s concentration on fight closeups, as in an early live TV drama, relieve the actors of the obligation to mimic their real-life counterparts. William Devane superbly captures JFK’s intelligence and courage and Sheen is fine as Bobby. Devane’s performance gave unexpected inspiration to Alfred Hitchcock, who told me with wicked glee on the set of his 1976 film Family Plot, “I have the actor who played John F. Kennedy playing the villain in my movie.”

That promising young magazine publisher John F. Kennedy Jr., despite his TV acting debut on Murphy Brown, is still auditioning for the role of the media magnate in his own possible future biopic, Citizen Kennedy. Some day there may even be an adequate biographical film about his father, but don’t hold your breath, because there hasn’t yet been an adequate print biography of JFK. The entertainment media still seem to think the public prefers the romanticized version of the Kennedy saga to the truth. Although the darker side of the saga has been dealt with extensively in books, few fictionalized films or TV movies have ventured beyond hagiography. Even Stone’s JFK is guilty of overly idealizing its title character. I spent some time in Hollywood in the early 1980s trying to convince studios to make an unvarnished biopic of the paterfamilias, Joe Kennedy. Almost everyone was afraid to touch the subject for fear of trouble from the Kennedy family, which, however diminished, still remains a powerful force in American life.

Editor’s Note: This article was originally published in the August / September 1999 issue of Irish America. ⬥

Leave a Reply