He could have been a bartender, instead Dylan McDermott is one of Hollywood’s hottest leading men. Coming off the unprecedented hat-trick of being TV’s Best Actor (according to the Emmys and the Golden Globes), becoming one of TV’s “Ten Sexiest Men” (according to People Magazine), and, most importantly, becoming one of the Top 100 Irish Americans (according to this magazine), McDermott is spending his summer in the plains outside Calgary, Canada, shooting a traditional Hollywood western, Texas Rangers. The actor took time out from shooting to talk about his often difficult path to stardom: losing his mother at age six, growing up the son of a New York City bartender not much older than himself, and the long dry spells that preceded his breakout role as defense attorney Bobby Donnell on TV’s The Practice.

Texas Rangers may be “just a movie,” but that doesn’t make round any softer when you’re thrown from a horse.

On a dirt road ten miles south of Calgary City, the flashing lights of an ambulance have halted an entire film crew, the result of a spill that busted the ribs of an unlucky extra. Actors, stuntmen and dozens of real-life cowboys and rodeo hands stand along the dusty farmland that has been converted into a Hollywood set, smoking cigarettes and leaning on their muskets silently, in the early morning haze. As the injured man is carted away, Dylan McDermott — the Texas Rangers leading man — assesses the risks of filming such an old-school western shoot-’em-up.

“Riding the horses is okay until the bombs start going off,” says McDermott, now out of his 1870s cowboy gear and relaxing in a Puma T-shirt and grimy blue sweats. “The bad guys are shooting guns, you’re shooting guns, and you gotta hit your marks, so there’s a lot to worry about. I feel bad for him [the injured rider, now in the ambulance and heading for a local hospital] because it’s so easy to get hurt. A horse can get skittish, freak out and throw you right off.”

The production is a risk beyond busted ribs. It is a classic western period piece, in an age when classic western period pieces often fail.

And its stars are not traditional screen bigs but rather TV actors on summer vacation (McDermott, on leave from ABC-TV’s The Practice, is joined by James Van Der Beek of UPN-TV’s Dawson’s Creek and Ashton Kutcher from Fox-TV’s That 70s Show), and a pair of moonlighting musicians (country legend Randy Travis and hip-hop artist Usher).

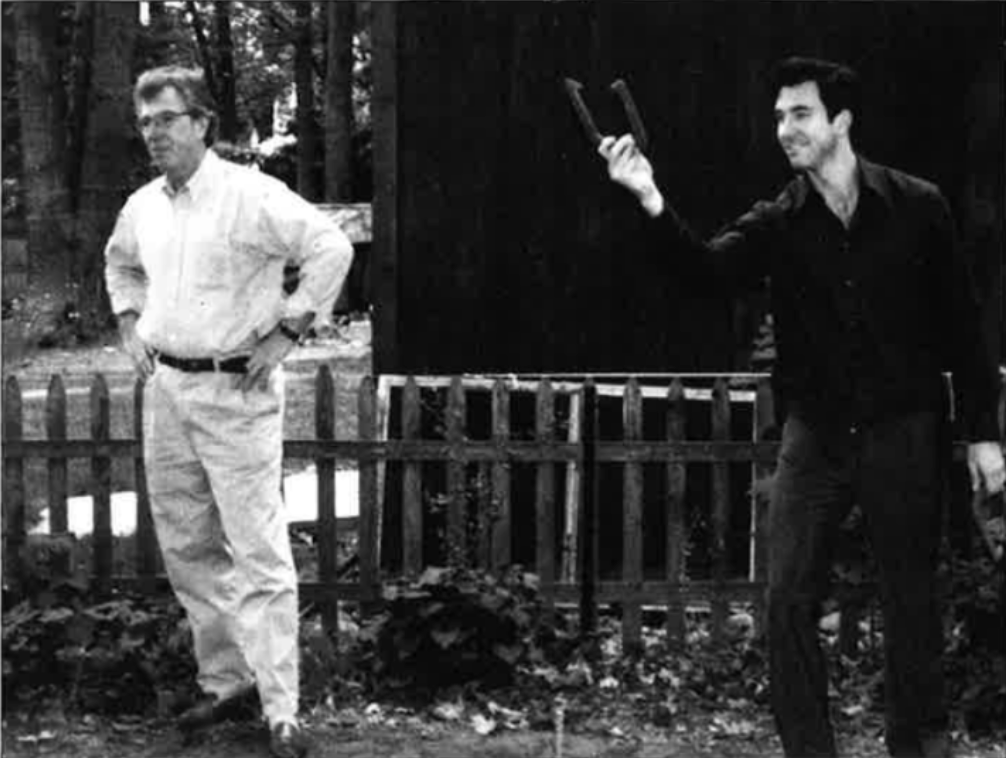

To sum up, Texas Rangers features an unlikely cast, a hit-or-miss genre and plenty of chances to get bucked from your saddle. For McDermott, the risks are nothing new. Riding a horse is nothing compared to his first film job, shooting combat scenes in the Philippines for John Irvin’s 1987 Vietnam War drama Hamburger Hill.

“Now that was a tough movie,” McDermott says. “There was a firefight and a battle sequence on the set yesterday and it reminded me of how difficult Hamburger Hill was to make. Back then, my helmet was my trailer. We all had to go through boot camp to get in shape for the role. And tragically, two people died while making it, down in the Philippines. I think it’ll go down in history as the hardest movie you’d ever want to make — physically and emotionally exhausting, and the combat scenes were so real they were scary.”

A dozen years later, McDermott is a star, with his own (modest) trailer in this muddy back-lot outside Calgary, the leading role on TV’s hottest, award-winning drama, and a loving wife and daughter back home in Santa Monica. At the age of 37, he is poised to join the ranks of Hollywood’s elite leading men.

“Hamburger Hill was hell at times but I was only 25, so of course you don’t mind,” McDermott says, reminiscing. “It’s things like that,” he says, looking around the set, “things like that are what get you here.”

Waterbury, Connecticut, October 26, 1961 — Mark Anthony McDermott is born to a pair of Catholic teenagers: the Italian American Diane, only 15 years of age, and the Irish American Richard, just 17.

“It was a scandal I’m sure,” laughs McDermott, who was forced to shed his birth name of Mark Anthony because of another Mark McDermott already in the Screen Actors Guild. “They were so incredibly young and here I was, the newborn baby, but my parents were a couple of kids so in love with each other, it was like they barely noticed the scandal of it all.”

Waterbury was a tough place, a working-class neighborhood in which Dylan says the McDermotts were one of the few white families. They were happy, with a pair of loving and supportive grandmothers. A few years later, the McDermotts had another child — this time it was a daughter, Robin. Six months after the birth of Dylan McDermott’s little sister, tragedy struck — 20-year-old Diane died. Dylan, who was only six at the time, is still haunted by the death to the point that he habitually refuses to discuss the circumstances of his mother’s death which was ruled an accident.

“No, I…I can’t to go into that,” McDermott says, fidgeting on the red vinyl couch of his trailer. “It’s…it’s just a rough one to talk about. It’s not something you really want people to read…we just don’t talk about it.

“You have good memories of a person and that’s what you want — you want to carry good memories. I was only 5 or 6 years old at the time but I do have a few memories of her. They’re my memories.”

Young McDermott and his sister were raised in Waterbury by his grandmothers, who struggled to send the kids to Catholic school. Richard McDermott, who by the age of 22 was a distraught widower and the father of two small kids, went to Brooklyn to work as a bartender.

“Dad was essentially a 21 or 22-year-old bachelor, just trying to find himself,” McDermott explains. “It just made sense at the time for me and my sister to stay with my grandmother rather than go with my Dad.”

Both grandmothers had a hand in raising the McDermott kids, in between arranging visits with their father on the weekends. Throughout, Dylan says he was very aware of ethnic roots.

“Well, my grandmother and grandfather were both very Irish, and that was embedded in me,” McDermott said. “Their parents — my great-grandparents — had come from Ireland, and although I didn’t know them, they were certainly talked about quite a bit. It was just there; it was innate, that we were Irish. It was clear to me from the beginning. Then when I went to school and I started reading Eugene O’Neill and Oscar Wilde and James Joyce, I started to understand the poetics of what Ireland was.”

As young McDermott grew older, the bar would come calling. His dad Richard was by then known as “Mac” to the locals in the West 4th Street Saloon in Greenwich Village. McDermott was spending increasingly more time with his father, working as a busboy beginning at age 13 and then as a waiter and finally a bartender, sharing an apartment with Dad and soaking up the sights and smells of the bar, observing its characters.

“Well, let’s see, there was a longshoreman bartending, Benny — he would take his glass eye out and squirt it with club soda and put it back in,” laughs McDermott. “Then there was Charlie Murphy — a total ladies man, always had the cigarette in his mouth, ashes going into the drinks. Mel Green, Jimmy Dea — these were all my father’s friends. All these characters, most of them are dead now. I don’t know exactly what they taught me but they’re always with me, in my head.

“I would mop the floor and play the songs they wanted to hear on the jukebox, I would break up the fights with my father. These were like real-life Eugene O’Neill characters: the hard drinkin’, hard smokin’ guys who didn’t live long but lived passionately. If I learned anything from them it was their passion.”

Mac — who sold his Greenwich Village bar in 1995 and currently works on the Upper East Side at a place called J.G. Melon’s — remembers his son as efficient, friendly, and, even as a teenager, a hit with the ladies.

“He was a fabulous bartender, charming, quick, all the women loved him,” recalls Mac proudly, speaking from behind the bar at J.G. Melon’s. Father and son were sharing an apartment in Manhattan, and both were enjoying the late-night lifestyle: working side-by-side behind the stick at the West 4th Street, a ball-and-a-beer joint that had been discovered by actors, writers and theater people.

“We were more like brothers than we were father and son,” Dylan remembers. “We still are, I guess that has something to do with him being only 17 years older than me. We had a lot of fun together, maybe too much fun, all the comings and goings and late nights and older women, which eventually led to his decision that I’d have to get my own place. He got me an apartment right next door to his own. Down at the bar, there was the fighting and the liquor and all of that — they seem to go together — but I always remember myself as more an observer, I guess that’s the artistic side of me. As long as I remember, I’ve always been observant of people and situations. Growing up in a bar, I mean, it’s a perfect kind of backdrop for all that — to watch people and see how they behave, to see what you want to be like.”

When Dylan was 16, Mac married for the third time (his second marriage was a brief encounter in the 1970s). Dylan’s new stepmom was a playwright — Eve Ensler — who saw something in her stepson that to her indicated promise as an actor. Ensler encouraged young McDermott away from the bars and toward the stage.

“How did I escape? It was my stepmom,” Dylan says. “She said to me, ‘Why don’t you try becoming an actor?’ And as soon as she said that everything sort of clicked. I used to wait on John Belushi, William Hurt, Ray Sharkey — all these actors used to come into the bar — and when she said I should be one too, the penny dropped. I thought, ‘Wow, what a life.’ From that point on, the fantasy just grew and grew. I used to go up to Broadway and watch the actors come out of the stage door, and picture myself doing that one day.

“When I started taking acting classes, that fantasy life sort of took over,” Dylan continued. “Working in the bars back then, you know, you’re just a kid and you’re taking $400 in cash a week and you party, all the time, but as soon as she said that, bartending just didn’t interest me anymore. When she said that, it changed my life.” [Ensler and Mac split some time ago but she and Dylan remain close].

McDermott told his father he was quitting the bar life.

“My old man was always supportive; he never questioned it,” Dylan remembers. “He always believed in me, he just said, ‘Go ahead and do it.’ He didn’t say, keep the day job and then do the acting on the side. He told me to go for it, forget about everything else. So I didn’t have anything to fall back on, which looking back now I know was a good thing. I encourage people nowadays to just live your dream — go out and do it, because if you have something to fall back on, then you most likely will fall back on it.”

As Mac remembers it, he had no reason not to have faith in his son.

“It never occurred to me he would be anything but a great actor,” says Mac, now 55 years old. “He could mimic anyone when he was a kid. He used to mimic me all the time.”

McDermott laughs at the memories of his father’s encouragement.

“Fortunately for me,” he recalls, “my father was never the most practical guy, so it probably never occurred to him that I should have something to fall back on. And it worked. I was forced to go out and get a job. An acting job.”

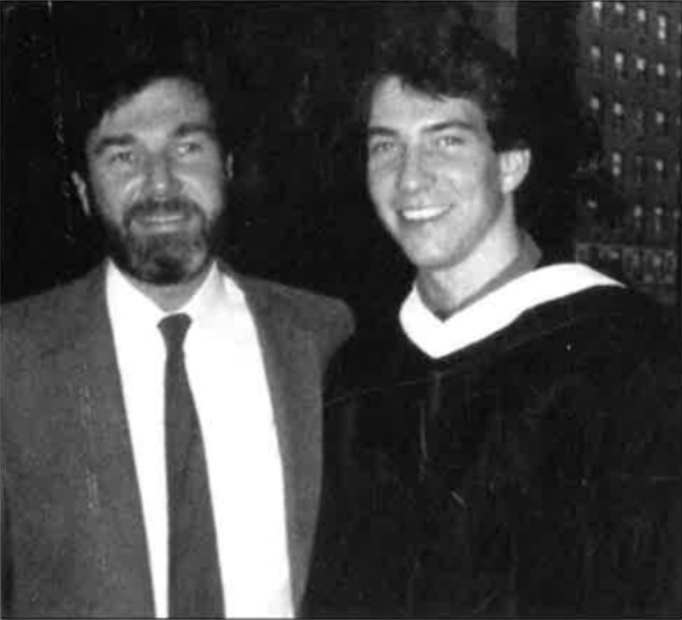

McDermott soon acted in one of his stepmom’s Off-Broadway productions. Mac bankrolled his son through Fordham University, where he studied acting. He joined the prestigious Neighborhood Playhouse group and acted in numerous productions, one of them opposite Joanne Woodward, and was discovered by the Hamburger Hill casting agent thanks to his part in Nell Simon’s play Biloxi Blues. Along the way, S.A.G. regulations forced Mark Anthony McDermott to change his name. He chose Dylan, partly out of tribute to the Welsh poet Dylan Thomas but also partly in response to yet another tragedy to strike the McDermotts.

“My father was going to have a baby with my stepmother and they were going to use the name Dylan,”

McDermott explains. “But there was a miscarriage, so the name kind of fell to me.”

Hamburger Hill won raves for the 25-year-old unknown, prompting talk of imminent stardom. Unfortunately for the young actor there began a string of bad luck and often worse movies: the poorly-received 1988 comedies Blue Iguana and Twister (not to be confused with the tornado movie made a decade later); the forgotten Hardware (1990) and Where Sleeping Dogs Lie (1993), and such critical and commercial flops as The Cowboy Way (1994) and Destiny Turns on the Radio (1995).

Not all of McDermott’s outings were disasters (for example, he was directed by Jodie Foster in Home for the Holidays and had a small but well-received part in Steel Magnolias), but for much of the decade following Hamburger Hill it seemed as if the actor’s best decision had to do with a role he wisely didn’t take — in the laughably awful 1995 film Showgirls.

“Everyone has to fail at some point,” McDermott says. “The movies that I made, maybe they were bad decisions, but I think I had to have had all that experience to get where I am today. I wanted to get the good roles, but not everyone can get that string of successful movies one after another. Not everyone can be Tom Cruise.

“But you know, for me there was just no other way. It got me where I am today, and now I am smarter and wiser and better, ultimately, in my acting,” McDermott continues. “I probably needed to grow up, I needed to mature. I knew I had to understand a lot more before I could be successful. Tell you the truth, I’m happy [success] didn’t happen then, because I probably would’ve pissed it away. I wouldn’t have been able to handle it.”

Even McDermott’s most successful outing — as Clint Eastwood’s Secret Service partner in the acclaimed In the Line of Fire (1993) — was less-than-fulfilling, i.e., Dylan’s character died early.

“My career was kind of plodding along,” McDermott says. “I was making money and I was doing alright. I was getting good roles, but I was dissatisfied with where I was at.”

McDermott’s personal life was also in disarray. For about 15 minutes in the mid-1980s he was famous for being yet another fiancé of actress Julia Roberts (she left McDermott for Kiefer Sutherland, whom she then left for Jason Patric, Lyle Lovett, etc.).

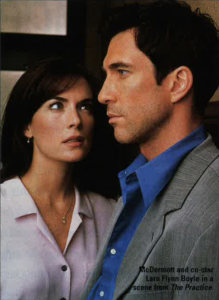

Then, in April 1996, McDermott auditioned for a TV role in a new drama, The Practice, written by David E. Kelley, the TV writing whiz behind Picket Fences, Chicago Hope and Ally McBeal. With his roots in Broadway and the silver screen, McDermott wondered whether he was making the right move by going for TV, but he says the strength of Kelley’s writing and the depth of the lead character — the scrappy and idealistic defense attorney Bobby Donnell — convinced him.

“Oh man, [The Practice] has been the saving grace of my career,” McDermott says. “David Kelley is the fast person who has been able to take me to that next level, purely because of his writing. Every week, he takes me to a place I need to go as an actor. My instinct on whether I should take the part was just `Yes! Yes! Yes!'”

Critics from the outset hailed The Practice, but amazingly, ABC nearly bungled the entire production. The show was moved from time slot to time slot, and its ratings were in the cellar as a result. Before long it seemed as if The Practice was destined to join the long line of critically acclaimed TV dramas that are unable to develop an audience and are quickly orphaned by the network.

“When the show started faltering I said, `I can’t believe this!'” McDermott remembers. “Everything is saying, `Yes!’ What’s going on? Why isn’t this working?”

There were entire parts of my childhood that I wouldn’t recommend to anybody, for me as an artist, if I can use those parts in a positive, constructive manner, if I can keep the memory of my mother alive in my work, then it’s a good thing.”

– Dylan McDermott

ABC finally made way for The Practice by airing it on Sundays at 10 p.m. (Eastern), ending a long tradition at the network of Sunday night movies. “They created the time slot for us on Sunday night,” McDermott says. “The movies had been there for years and years, so I’m really grateful they gave us the chance. Of course, they very nearly dropped the ball a couple of times. What’d we do? We went off and won the [Best Drama] Emmy.”

About to enter its third season, The Practice has been lauded by the Emmys, The Golden Globes and perhaps most importantly, the Nielsen ratings. The show has also launched McDermott into the sex-symbol stratosphere, a status he obviously understands as a by-product of his business, yet one that he’s not altogether comfortable with. His famous blue eyes, normally set dead straight ahead, drift away when he is asked about the Top 10 lists, about the dozens of adoring Internet sites, about the legions of female fans who call themselves the “Dylanites.”

“The ‘Dylanites’?” he says incredulously, looking at a fan newsletter downloaded from the Internet. “Now that one’s news to me. I don’t know — I try and take all this sex-symbol stuff with a grain of salt. I’ve been doing this since I’m 25, and I’ve been around people who’ve had that kind of superstardom, and then not had it. I try to look at it as what I do; and I try not to take it seriously. The best way for me to look at it is, if it goes away tomorrow will I still be OK? Y’know, with me? For a lot of actors, it does go away, and it’s not okay. It’s a hard lesson and I see it constantly. Friends I know, guys I see. And it scares me, so I try to not let any of the sex-symbol stuff get to my head. I think every actor’s nightmare is to be that walking milk carton, with an expiration date.

“Besides,” he laughs, “I really can’t complain, because there are worse things. I could’ve been named to the Top Ten Ugliest lists.”

Personally, McDermott’s previously stormy single life began to settle in 1992, when he spotted half-Persian, half-Irish actress Shiva Ashfar in a Santa Monica coffeeshop. McDermott says he instantly “had a feeling” about Ashfar, then 20 years old, and he introduced himself. In 1995 they were married, and in 1996 Ashfar gave birth to their daughter, Colette. In January 1999, McDermott accepted the Best Actor award at the Golden Globes by proclaiming from the stage, “To my beautiful, beautiful wife and daughter — without you, I am nothing.” [He also mentioned that the only other award he had received in his life was being “an Irish American Top 100”]. At the age of 37, McDermott has the house, the wife, the kid and the steady family life that his father never seemed to have. Was that by design?

“I think I did kind of seek out that lifestyle,” McDermott says. “I wanted to have some kind of permanence in terms of family. It’s important for me to have that, even though it’s hard when you’re an actor. My relationship with my wife and my daughter is the most important thing in the world to me, and I think that probably comes from having come from a broken family myself. I must’ve established that desire in my own psyche, it was something I always craved.”

Professionally, things couldn’t be better, with a comedy, Three to Tango (co-starring Neve Campbell and Matthew Perry) due out in the fall. Texas Rangers is due to wrap in late July, after which he will immediately start taping the next season of The Practice. The first order of business in the new season will likely be Bobby Donnell’s engagement — in last season’s finale, Donnell proposed to his legal colleague Lindsay (played by Kelli Williams). McDermott says he has “no idea” whether David Kelley will allow Donnell to actually go through with the wedding, or whether there will be a follow-up to last season’s highly-rated pair of crossover episodes between The Practice and Kelley’s other current hit, Ally McBeal. McDermott says he’ll continue to play Bobby Donnell “for as long as David Kelley keeps writing and for as long as the shows are as good as they are now.”

McDermott also wants to direct more -last season he directed one episode of The Practice, and before his stint on The Practice, he directed theater, even winning a 1994 Drama Desk award for directing Short Eyes. In his spare time, he has been working for the past couple of years on a novel, a first-person narrative told through the eyes of a young boy who loses his mother, a story that resembles McDermott’s real-life experience.

“Obviously, something like that [losing your mother at such an early age] is going to affect you, and if you’re an artist it’s going to appear in your work,” McDermott says. “For example, the character I’m playing now [in Texas Rangers] comes home from the Civil War and he’s lost his entire family. As an actor you need to be able to relate to that and for better or worse, I can. You can’t act this stuff, you can’t teach it, you gotta have it.

“For me as an artist, it’ s a great thing to be able to use such a tragedy constructively, even though for me as a person it’ s not the greatest thing. There were entire parts of my childhood that I wouldn’t recommend to anybody, but for me as an artist, if I can use those parts in a positive, constructive manner, if I can keep the memory of my mother alive in my work, then it’s a good thing.”

With the family, the show, the movies and the book, McDermott hopes to find time for one last thing: he says he’d love to visit Ireland with his father.

“The few times I’ve been there [to Dublin] I really loved the place — I was acting in London and it was so dreary there, and I’d go to Dublin on the weekends and it was so full of life, with people inviting me into their houses for tea and music. There was such a sense of life and energy.”

He says he’d love to go with his father to visit Cork, where his great-grandfather came from, and Tipperary, where his great-grandmother came from. “My dad’s been there, but I’d love to go with him sometime. I’ll have to take the trip one day; I really want to.”

Currently, Mac is enjoying newfound stardom, thanks to the women who come into J.G. Melon’s in the hopes of seeing his sex-symbol son. Will Mac ever give up the bar trade?

“Oh I don’t know about that, he enjoys it too much,” Dylan says. “He’s been doing it for so long, since he was 20 years old y’know? He could retire at this point but why? He’d be bored to death. There are endless amounts of things you can learn in a bar, and he’s still learning them. When I go home to New York to visit him, he always has something else new to teach me.”

Editor’s Note: This article was originally published in the August / September 1999 issue of Irish America. ⬥

Leave a Reply