In 1996, a new play by a young London writer opened in Galway, Ireland with an all-Irish cast. In June of this year, that same group of actors swept the boards at the Tony Awards ceremony on Broadway. Patricia O’Haire spoke to the cast of The Beauty Queen of Leenane.

All in all, it was a great day for the Irish.

That was the consensus of most of the news media gathered at Sardi’s restaurant one cold May morning earlier this year to hear the list of this year’s Tony nominees announced.

In just about every category for a straight play, the name of the Irish entry, The Beauty Queen of Leenane, was read. Six nominations it had, the most of any play this season. One for each of the actors — Anna Manahan, Marie Mullen, Brian O’Byrne, and Tom Murphy — one for director Garry Hynes, and another for playwright Martin McDonagh. (The Chairs, a British import, also had six.)

It was a sweep as clean as any made by a brand-new Hoover.

And when the Tonys were announced on the first Sunday in June, the choice of the play was validated. Beauty Queen won four of the six prizes it was nominated for — more than any other straight play (The Chairs was shut out), losing only as Best Play to the English import Art. Unfortunately for Brian O’Byrne, he and his colleague Tom Murphy had both been nominated in the same category, and it was Murphy who won Best Featured Actor.

Three of the actors won in their categories: Marie Mullen took the prize as the year’s Best Actress; Anna Manahan and Tom Murphy were named Best Featured Actress and Actor.

Director Hynes and Murphy both made a bit of history on the show, which was telecast nationally on CBS. Garry Hynes was the first woman ever to win in the Best Director category.

Murphy’s feat was that he became the first person ever to use the “f” word onstage and out loud while accepting his award during the telecast. But since he used the Irish “feckin'” — a word he uses frequently in character onstage — and because it was a live telecast, he escaped the usual bleep of the censors.

The Tony Awards are to the Broadway stage what Academy Awards are to Hollywood, and the fact that the entire cast found their names on the nominating list was a great tribute.

Only two — Manahan and O’Byrne — had ever been on a Broadway stage before. Manahan trod once in 1969, in an early Brian Friel play, Lovers, which also starred Art Carney, and which brought her a nomination, but not an award. O’Byrne was in The Sisters Rosenzweig, the Pulitzer Prize-winning play by Wendy Wasserstein, which won a Tony as Best Play in 1993.

Beauty Queen has a happy cast, and not only because of the recognition. The four have been working together off and on since the show first played almost three years ago at Galway’s celebrated Druid Theater.

“We four are the original actors and I think the best,” Anna Manahan says with conviction. “Not to say the others who did it weren’t good,” she hedged, “but there’s something about being the originator of a role. It’ s sort of yours forever.”

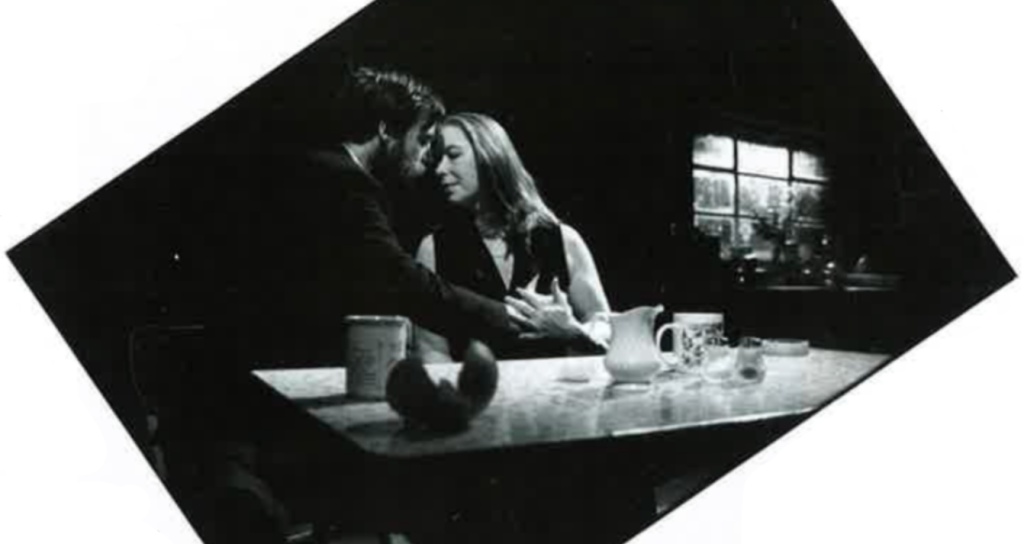

Beauty Queen is the story of a manipulative, conniving mother-from-hell living in a barren cottage in a small Connemara town with her daughter, Maureen. Mag (Manahan) Folan is the kind of mother whose daughters live as far as possible from her querulous voice, but they sometimes feel guilty so they visit at Christmas with husbands and kids, then leave as soon as they can. Mag sits at home all day, wrapped in a ratty sweater over a faded housedress, watching the telly and waiting for 40-year-old daughter Maureen to make her tea and hand her biscuits — after all, she’s not well. She has this “your-rine” infection and lives in the real fear she’ll be abandoned, or worse, sent off to a home.

Maureen (Marie Mullen) is the only child left at home. Her social life consists of maybe greeting a neighbor or shopkeeper or talking to the chickens they keep. She gets more frustrated with each passing day and more angry.

Brian F. O’Byrne is Pato Dooley, a neighbor down the road, on a visit home from his job in England, who upsets the living arrangements, such as they are. Tom Murphy is Ray, his fidgety younger brother, who’s about 19 and as anxious as anyone in town to escape.

Offstage, the four actors have taken to New York as if they were natives. O’Byrne, the only nonwinner, is engaged to an American, and he and Murphy usually set forth on a voyage of discovery nightly of the town’s Irish pubs; Mullen, whose two young daughters are with her, lives near Manahan on the Upper West Side.

The tall, slim, bearded O’Byme seems always ready for a laugh. He comes from Cavan, but had left home by the age of 19. By then, he was living in Dublin, studying video and TV production while deciding what to do with himself, if anything.

“I got into acting totally by chance,” he says. “My two mates were auditioning for a course at the Samuel Beckett Institute, which had just been established at Trinity College, and I went along, probably out of fear of losing them. We did an improvisation, and they asked us to come back and do a modern piece and something from Shakespeare.

“Well, what did I know? I was a roadie for rock bands then, setting up amps and instruments, so when the time came for me to do my modern piece and my Shakespeare, I told them I’d been working so hard, I hadn’t time to prepare.

“They believed me! And still they took me in!”

He’s had luck like that over the years. He’d lived in the States several years, worked Off Broadway in a play called Grandchild of Kings, a theatrical adaptation of two of Sean O’Casey’s autobiographies. That led to a role in The Sisters Rosenzweig, then another in Tom Stoppard’s Hapgood.

He went home after that, to work at the Abbey and the Gate in Dublin, then to Galway for Beauty Queen. “I’m in it totally by default,” he says. The actor who was supposed to have the role got ill and I took over.”

His role is that of the neighbor courting Maureen, and in his one solo scene, in which he reads aloud the letter he’ s written to her, he commands the stage with quiet authority.

“Pato’s a beautiful, simple character,” O’Byrne says. “All heart. Not sophisticated, doesn’t need to be. A traditional, hard-working, respectable country man — even if he does go to bed with her.”

Asked if he’s been getting any offers for film or TV now, and he looks up and grins widely. “I expect to be deluged with scripts,” he says, mockingly. “Matter of fact, I’ve cleared out a place under my dressing table to keep them,” and he points to a spot completely bare.

The Tony Awards are to the Broadway stage what Academy Awards are to Hollywood, and the fact that the entire cast found their names on the nominating list was a great tribute.”

Anna Manahan, the mean old mother, sees herself everywhere these days. The play is being advertised on the side of most of New York City buses, and you can’t miss Anna’s photo, in an old dressing gown, peering suspiciously over her shoulder. She’s settled now into a small apartment a short walk from Central Park, and spends her off time looking up friends she’s known since when she was in Lovers.

“I’ve probably seen more of this country than a lot of its citizens,” she says. She’s right. When Lovers ended its Broadway run, she and co-star Art Carney went on a national tour for six months, playing one or two weeks in one town, three in another. She’s happy now to be settled in one spot for a while.

“We traveled a lot with this play, too,” she said. “All over Ireland, even out to the Aran Islands, England, Australia. It’s a wonder I’m not poisoned — I have to eat a lot of porridge onstage, and some stage managers make porridge that’s really concrete!”

Manahan, who’s not too tall and not too slim, is from Waterford, where she owns a house she’s seldom seen. “I thought by this time I’d slow down, live at my home with my two unmarried brothers and my cat. Not a bit of it! I’m working harder than I ever did before! I’m looking forward to when this play is over and I’ll take a chair out into my garden, sit under my cherry tree and look at things!

“Not that it bothers me. There are actresses my age looking for work and can’t find it. And believe me, this role demands energy and vigor and lots of it.”

Manarian, a widow whose age is as secret as an FBI file, has had a wideranging career. She was a member of Dublin’s Gate Theater; John B. Keane wrote his play, Big Maggie, for her. She’s worked at the National Theater and the Royal Court in London, the Abbey in Dublin, and in both films and TV. Now since she’s been in several McDonagh plays there, she calls the Druid home.

Marie Mullen, small and with dark reddish hair, comes from Sligo, but she met Garry Hynes when she went to college in Galway. There, in 1975, the two and actor Mick Lally (who was a teacher at the time) decided to form a company which they called the Druid to put on plays. “We rented the local Jesuit Hall,” she says, “and with great glee, we put on three plays over the summer. We did well enough, managed to get a grant and went looking for a permanent theater. Found one, too — it had all of 48 seats.

“We worked at it and the theater built up a following. It really began for us when we went to the Edinburgh Festival in 1982 and won the Fringe first prize. After that, people started to take notice. Critics came from Dublin to review us.

“My mother and father loved the movies, and we went often and I loved going with them, and I think I got a sense then of what was good and what was bad in the acting world. I can’t ever remember saying to myself I’d die if I couldn’t be an actor, yet I always had an inkling I’d like to do it. I suppose I just loved the idea of playing a character, being someone else. It’s easy to get excited by a particular part, especially one like this Maureen.”

She’s played the role almost continuously, only taking eight months off to have her second daughter, now 15 months old (the older is six). She and her husband, actor Seen McGinley, bought a house in Dublin, where they live now. He’s off in Wales, working; they were married in 1990.

Tom Murphy, who plays younger brother Ray Dooley, charged with delivering messages to the lovers, is a 27-year-old who has lived in Dublin most of his life, though he was born in Zambia, in Africa, where his father had a construction company and his mother was a norse.

Murphy’s a bit more subdued offstage than the antsy Ray of the play, who always seems anxious to be somewhere else — anywhere, except where he is. He’s a bit shorter than Brian, with close-cropped hair and a rapidfire way of talking.

He’s been acting on the stage in one way or another since college (like O’Byme, he too went to Trinity), but only began taking it seriously about four years ago, when he hit 23. Last year, he took a bit of a break from the stage to make a film, The General, about Ireland’s crime boss, Martin Cahill.

“I like to go from job to job, but I really like it here in New York,” he says. “I like the energy, might like to stay a while, try it out. As it is, we can work only a certain amount of time before American actors come to take over our roles.”

Because the cast members (with the sole exception of Brian O’Byrne) are not members of Equity, the actors’ union, they may not be allowed to perform the show past their October deadline.

Although he’s enjoying his stay in New York. Murphy is also quick to recognize what he calls the “virtues” of Dublin. “For a place its size, it has so many theaters, so much going on,” he says. “You can almost always get work.”

When he was still in college, he did a workshop at the Druid Theater for director Garry Hynes, who sent him the Beauty Queen script. He auditioned for the role and was cast immediately.

“Ray’s an odd sort of character,” he says. “Bordering on being dangerous. He’s got a major sense of frustration and may get violent. You have to remember that this takes place in a small town in Connemara. The land is harsh there, which makes some of the people harsh, too.

“This fellow Raymond, he lives on his nerves. He s probably only recently given up biting his nails. The guy cannot sit still — if he does, he’ll explode, fly all over Connemara. But there’s a wonderful spirit in him as well. He wants to go out and explore. I can identify with that.”

Obviously, the theater community felt the same way. They recognized what each of the actors was doing and responded to it in the best way possible: they heaped awards on them. To paraphrase actress Sally Field — who once gasped “you like me, you really, really like me” in a memorably emotional Academy Award acceptance speech — New York’s theater community showed how much they “really, really liked” the cast of Beauty Queen.

Editor’s Note: This article was originally published in the July/August 1998 issue of Irish America. ⬥

Leave a Reply