Rory Keohane looks at the success of American female dance champions and the influence of Riverdance.

A light Easter Sunday rain fell on the parishioners as they flowed from Sunday mass into the quiet streets of Ennis, a sprawling town in the western county of Clare. On this day, the local congregation played host to a score of ringlet-haired guests and their parents who converged on the area from far and abroad to compete in the World Irish Dance championships, the highest level of competition on the dance circuit. A few miles away at the West County Inn, over 70 competitors were shuffling and clicking in pursuit of one of the most coveted prizes of this week-long competition, the over-21 Ladies Championship.

Noelle Curren has spent the majority of her years dancing with the Peter Smith School of Dance in New Jersey. As last year’s Ladies World Champion in the 19-21 age category, she was relaxed with her position as a strong competitor, but as an American, she was not considered a favorite to win. In thirty years, only one American had taken home the senior title — Theresa O’Sullivan, in 1997.

Curren danced beautifully, after which she could do little but sit back and enjoy the mixed ceili competition, while the judges decided her fate.

Two hours later her petite frame mounted the podium, with crown and sash designating her the last over-21 Ladies champion of the millennium.

“I wasn’t expecting to win this year,” Curren said modestly. “Normally when you move up into a new age group, you don’t win for a of couple years, but it’s good to have two American names on the cup.”

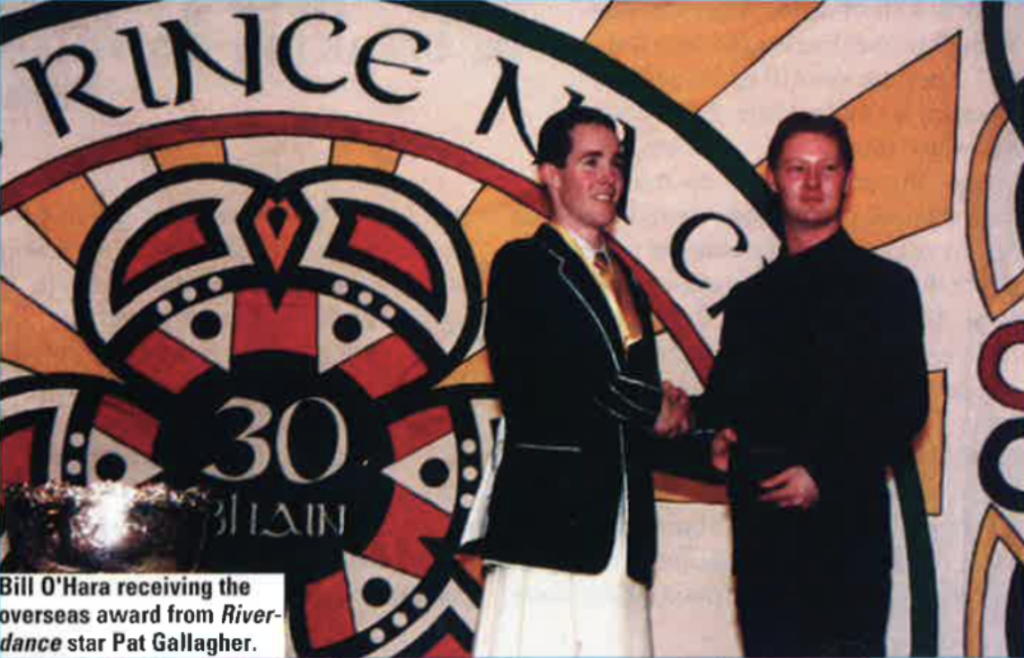

Curren was joined on the winners’ podium by another American, Kathleen Keady of the Schade School in New York, who placed third and also received the Overseas Award, originally created to encourage foreign entries.

According to Dr. John Cullinane, a member of the governing commission, An Coimisiun le Rinci Gaelacha, and author of numerous books on Irish dance and costume, there was a great disparity of talent between Ireland and other countries in the early years of the World Championships.

“At that time, the dancing in Australia and America was way behind Ireland, and when they came over in the first years, they were just not in the running.” As the Irish Dance Commission celebrates its 30th anniversary, it is evident that there is a worldwide circuit developing of equal talent and ability. And now, equal reward. “The overseas award may soon have outlived its original function,” said Cullinane. “American dancers are now coming over and challenging us successfully on our own home territory.”

O’Sullivan’s victory in 1997 was the turning point for American female competitors. “It opened the door for women from America,” says Amy Siegel, also of the Smith school, who, the day before, had became the World Champion in the 19-21 age group. “There had been men who won, but no women before her.”

On one hand it is very good that the dancers have an outlet and can travel the world earning good money. But on the other hand, the actual art form seems to be breaking down a bit.”

– Jean Butler

The path for American men was paved by Michael Flatley in 1975, when he became the first American to capture a World Title. When he later went on to conceive and star in Riverdance he brought Irish dancing to a worldwide audience. The success of the show influenced the competition, affected the style of dance and costumes and sheer numbers of dancers.

One change brought about by Riverdance, obvious to even the most casual spectator, is the aesthetic of the male competitors. Borrowing from the Scottish tradition, An Coimisiun le Rinci Gaelacha introduced kilts to dancing in the 1920s. For the next 70 years, they were the customary costume for male competitors. Flatley introduced a more macho garb of black pants and a flowing black shirt, and turned the trend away from the kilt. This has been a positive move for many of the younger boys competing in the Championships.

Alan Kenefick, of Tivoli, a town on the outskirts of Cork City, won the World Championship for boys age 13-15. Riverdance, particularly the change in his attire, sustained his young dancing career. “It has kept me in it,” he says in his sing-song Cork accent. “I might have gone out of it, you know, wearing all the kilts, but now we wear pants and the shirt and a stylish tie. It’s cool.” Riverdance has also established a future for those who wish to continue dancing outside of competition. “I’d go if I was asked in the morning,” said Kenefick, wide-eyed at the possibility of joining one of the touring companies.

The dancers of Kenefick’s generation represent the last few age groups of boys to have worn kilts before the Riverdance phenomena. However, there are still a few dancers who prefer the older style of dress. Kieran McAuliffe, from the Doherty School in Coventry, England, was one of only two dancers, of the 45 who participated in the Boys 17-19 competition, to wear a kilt. “I wore trousers last year, and it just doesn’t suit my style of dancing, so I changed back” he says. McAuliffe is not as concerned with the influence that Riverdance and other Celtic-based shows have had on the costumes but is concerned for the individual dance schools which trained these now professional dancers. “I’ve had quite a few friends who have gone into shows, and it has taken away most of the older people from our dancing class,” he says.

Many dance schools have witnessed an exodus of their older dancers lured by the professional opportunities provided by Riverdance and Michael Flatley’s Lord of the Dance, the other major Irish dance show. This lack of older students has decreased the number of schools able to field group ceili and figure dances at the highest levels.

Tom Farrelly, a soft-spoken man in his nineties, has been President of the Irish Dance Commission since 1979.

Adorned in a regal band of medals which denote his position, he absorbed all of the competition with a wise eye of experience. He notes that while Riverdance and similar shows may take some students away from competition earlier than in times past, it has created an enormous response around the world, resulting in greatly increased enrollment among younger students. “Naturally enough, things change, sometimes for the worse, sometimes for the better,” he said.

Nine-time World Champion and former Riverdance lead man, Colin Dunne, revisiting the scene that was his dancing life before professional opportunities arose, is ambivalent about the influence the professional scene has had on the costume. “At the end of the day, it does not matter whether you wear a kilt or a pair of pants. All that matters is if you can really dance,” he says.

At the end of the day, it does not matter whether you wear a kilt or a pair of pants. All that matters is if you can really dance.

– Colin Dunne

Dunne’s concern with the post-Riverdance competition is the drop in ability and talent in the older age groups. “One of the downsides to the professional shows is that it has moved a lot of the older dancers out of competition, so the standards have dropped, or so it seems. However, I am optimistic about the high standard for youngsters who were five or six when Riverdance first appeared on Eurovision [the annual European song contest which spawned the full-length Riverdance after audiences responded ecstatically to a short dance sequence featuring Michael Flatley and Jean Butler]. They are now 10 or 11, and the standard is just fantastic. It is a double-edged thing.”

Jean Butler, Flatley’s co-star in that original production, shared a similar sentiment towards the influence of professional dance shows on the traditional scene. “On one hand it is very good that the dancers have another outlet and can travel the world earning good money,” says Butler. “But on the other hand, the actual art form seems to be breaking down a bit.”

The visit by Butler and Dunne to the World Championships was for both business and pleasure. While the competition provide an opportunity to see old friends, they were also there to hold auditions for a new show which they hope will strike a more traditional chord than Lord of the Dance and Riverdance.

“I would hate to think that Riverdance and Lord of the Dance are the last statement that can be made about Irish dancing,” said Dunne. “It can move on, it has to. And it will.” Butler was quick to add that “moving on does not mean creating a new eccentric dance. It can be subtle, by embellishing but not bastardizing the form.” The new show is expected to premier in the fall.

There has been much discussion within Irish dance circles about the cost and benefits of the Riverdance influence on both the competition and the perception of Irish dance as an art form. Dunne justifies what many may consider modern interpretations of older traditions by encouraging personal and artistic dignity. “Any tradition is in the hands of the people who live with it now. It is where they choose to take it.”

On this Easter Sunday, from his reserved seat within the adjudicators box, President Tom Farrelly reflects on his 70-year membership with An Coimisiun le Rinci Gaelacha. He has trained and examined teachers first in North America, then in Australia, New Zealand, and even South Africa. He has seen the dance transformed from the old “rattling of the feet” to the traditional steps of the masters in Cork and Kerry, and now to the intricate footwork exhibited at this year’s competition. And, as he watches Noelle Curren proudly receive her World Championship sash, he offers a reflective commentary on modern Irish dance.

“Riverdance is loved all over the world,” he says, comparing the travels of these young dancers with his own, when as a young man he examined perspective dance teachers on four continents. “It is a chance to see the world,” he chuckles with a grin of jest. “And spread the Gospel truth at the same time.”

Editor’s Note: This article was originally published in the June/July 1999 issue of Irish America. ⬥

Leave a Reply