With the recent upsurge of interest in Irish cinema, such Irish-born directors as Jim Sheridan and Neil Jordan have become leading forces in international filmmaking. But the influence of the Irish Diaspora and the rich literary and dramatic culture of Ireland itself have left their mark on many filmmakers not born there. The Irish-American directors John Ford and John Huston repeatedly returned to Irish subjects and locations. Ford’s most beloved film, The Quiet Man, was made near his ancestral home in Connemara, and his other films with Irish subjects include The Rising of the Moon, The Plough and the Stars, and the silents The Shamrock Handicap, Mother Machree, and Hangman’s House. Huston, who lived in County Galway for many years, ended his career with his 1987 masterpiece based on a classic story by James Joyce, The Dead, although because of the director’s ill health he had to recreate the Dublin period setting in a California studio.

Over the years, Irish subject matter has proved a potent lure for such other major directors as Stanley Kubrick, whose 1975 film of William Makepeace Thackeray’s novel Barry Lyndon was partially filmed in Ireland; Francis Ford Coppola, who directed his first feature in Ireland, the 1963 horror film Dementia 13; Alfred Hitchcock, who filmed Sean O’Casey’s play Juno and the Paycock in England in 1930; David Lean, who directed his 1969 Ryan’s Daughter in County Kerry; Robert Altman, whose Images (1971) was the first official Irish entry at the Cannes Film Festival; and more recently Ron Howard (Far and Away, 1992) and John Sayles (The Secret of Roan lnish, 1994).

One of the American filmmakers most profoundly influenced by Irish culture was a man of English descent (all the way back to the Mayflower) who never directed a film in Ireland or one with Irish subject matter. But Orson Welles received his only professional training in acting and directing from two of Ireland’s most celebrated men of the stage, Hilton Edwards and Micheál MacLíammóir. On a visit to Ireland at the age of sixteen in 1931-32, Welles conned, charmed, or bamboozled (accounts vary) those legendary founders of Dublin’s Gate Theatre into hiring him as an actor, scenery painter and designer, and press agent. The lessons Welles learned from Edwards and MacLíammór during his six months at the Gate helped shape not only his subsequent theatrical career but also his distinctive style as a filmmaker.

On a Radio Telefís Éireann documentary about Edwards and, MacLíammóir in the 1960s, Welles said, “They gave me an education. Whatever I know about any of the stage arts today is only an extension of what I first knew from them.”

While earlier attending the Todd School for Boys in Woodstock, Illinois, and at Camp Indianola in Madison, Wisconsin, Welles had been encouraged to develop his interest in theater, stimulated by his parents’ acquaintances with actors and singers passing through Chicago. Orson’s already imposing voice and physique, his fascination with painting and makeup, and his natural inclination toward leadership made him a theatrical prodigy and attracted notice from Chicago critics. But after his graduation from the Todd School, Welles was emotionally adrift, not eager to attend Harvard and still reeling from the December 1930 death (officially from chronic heart and kidney disease) of his alcoholic father, who he believed had committed suicide. In a marvelous 1994 biography of Edwards and MacLíammóir, The Boys, Christopher Fitz-Simon makes a startling revelation: “According to [Irish actress] Geraldine Fitzgerald — who was too young to have worked with Welles at the Gate, but was a member of his Mercury Theatre in New York in 1938 — he had had a nervous breakdown following the suicide of his father, and was sent to Europe to recuperate.”

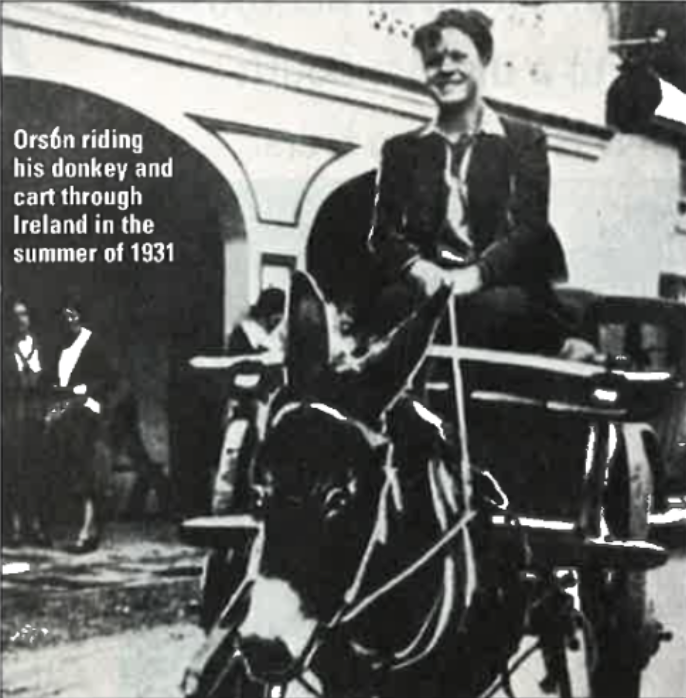

Welles arrived in Galway in August 1931 with $500 of his inheritance, ostensibly to paint and possibly to write a book about his travels. The big American lad whom the locals called “Paddy” bought a donkey and cart and wandered wide-eyed through the Irish countryside, which he found to be “a kind of lost Eden rich in romance and bounteous beauty.” When he visited the Aran Islands, Welles wrote that somewhere “there may be a forgotten land where eyes are as clear and hearts as open, but nowhere so remarkably combined with intelligence.” According to all the biographies of Welles, that autumn was when he had his first exposure to the Irish theater with a visit to the Gate. But I learned while visiting Galway in 1986 that Welles had staged a play in the back room of a bookstore in that city before heading off to Dublin.

What happened at the Gate has become the stuff of legend. Welles claimed that he introduced himself to Edwards backstage with the following note: “Orson Welles, star of the New York Theatre Guild, would consider appearing in one of your productions and hopes you will see him for an appointment.” He also claimed on some occasions that Edwards and MacLíammóir actually believed this preposterous lie, although he once admitted, “Hilton can’t have swallowed all that, but he was nice enough to pretend to, and he did start me at the top with leading roles.”

In his 1946 memoir All for Hecuba, MacLíammóir offered an equally colorful rendering of their initial encounter with Welles. He recalled Edwards telling him, “Somebody strange has arrived from America; come and see what you think of it.”

“What is it?”

“Tall, young, fat: says he’s been with the Guild Theatre [sic] in New York. Don’t believe a word of it, but he’s interesting. I want him to give me an audition. Says he’s been in Connemara with a donkey.”

They found “a very tall young man with a chubby face, full powerful lips, and disconcerting Chinese eyes. His hands were enormous and very beautifully shaped, like so many American hands; they were coloured like champagne and moved with a sort of controlled abandon never seen in a European. The voice, with its brazen Transatlantic sonority, was already that of a preacher, a leader, a man of power…It was an astonishing performance, wrong from beginning to end but with all the qualities of fine acting tearing their way through a chaos of inexperience. His diction was practically perfect, his personality, in spite of his fantastic circus antics, was real and varied; his sense of passion, of evil, of drunkenness, of tyranny, of a sort of demoniac authority was arresting; a preposterous energy pulsated through everything he did. One wanted to bellow with laughter, yet the laughter died on one’s lips.”

To Welles’ astonishingly good fortune, he arrived when Edwards was having trouble casting the role of the depraved Karl Alexander, Duke of Wurtemberg, in a melodrama called Jew Süss. Edwards took a chance on the youngster, who tore his passion to tatters on the opening night of October 13, 1931, dying with what he called a “frenzied back-flip” down a flight of steps. He received six curtain calls and became an instant celebrity in Dublin.

The Independent discerned “a touch of humanity and simplicity in his swinishness which in less expert hands might have been lost…Orson Welles captured it magnificently”; the Dublin correspondent for the New York Times called his performance “astonishingly fine.”

There was one disconcerting moment during his debut, however. When Welles lecherously declaimed the words, “A bride fit for Solomon. He had a thousand wives, did he not?” a patron in the stalls called out, “That’s a dirty black Protestant lie!” Welles later admitted he was `half dead from fright’ for the rest of the performance, having forever lost the innocence that had made him come out on stage like “a baby on a trapeze.”

Welles’ subsequent roles at the Gate were nowhere near as noteworthy as his first. He was relegated to smaller character roles, the best of which was the Ghost in Hamlet, in addition to designing plays and making an appearance as part of a small “art-theatrish stock company” renting the Abbey’s Studio, the Peacock Theatre. Welles continued to burnish his own legend in his capacity as press agent for the Gate and by writing odes to himself in a theater column he published in an Irish tabloid under the pseudonym “Knowles Noel Shane.”

Welles’ limited range and experience may have been the cause of his seeming demotion at the Gate; the Irish actor Cyril Cusack observed that the young Welles’ “personality overtook his acting.” But some have blamed his eclipse on jealousy between Edwards and the company’s star actor, MacLíammóir, over their new protégé. The two openly gay impresarios, affectionately known in Dublin as “Sodom and Begorrah,” referred to themselves in later years as “The Stately Homos of Ireland.” Their long relationship with Welles was complex and often laced with intrigue and recrimination. But the friendship they established with him in Dublin was strong enough that they accepted Welles’ invitation to help him stage three plays at the Todd School’s 1934 “Summer Festival of Drama.”

Welles’ mercurial rise to fame on the New York stage in the late 1930s seemed to come out of the blue, but the bold theatricality of his work as an actor and director was a legacy of his training by Edwards. As a director, Edwards was an enemy of naturalism, which he felt turned theater into a weak imitation of cinema. Seeking “the conscious realization of the presence of the audience,” Edwards believed that “when the theater once again makes its audience conscious of the presence of its art, people will go to the theater to see and hear a theatrical performance, and to the cinema to see a cinematic one. The theater will be the theater precisely because it is theatrical.”

Breaking from the Abbey Theatre’s tradition of devoting itself to Irish plays and subjects, the Gate offered an eclectic, cosmopolitan, often avant-garde repertoire. Welles was exposed to the most advanced ideas in European drama, particularly those of the German expressionist school. And though Welles always disputed critics who wrote that he was influenced by German expressionist cinema, it’s likely that style filtered down to him through its influence on the theater of Edwards and MacLíammóir. Edwards’ daring, innovative use of lighting, his fondness for rapid scene changes, and MacLíammóir’s poetic approach to stage design gave Welles indelible lessons in the importance of visual expression in the theater. His mentors also showed by their example that a man of the theater should be deeply versed in every aspect of stagecraft.

Welles incorporated all these influences into the first feature film he directed, Citizen Kane (1941), which he made at the age of twenty-five (playing a character with an Irish name; he later played an actual Irishman in his 1948 film, The Lady from Shanghai). Kane stunned movie audiences with its adventurous and unconventional lighting, camera angles, and storytelling devices, a boldly personal blend of theatrical and cinematic techniques. Welles continued to experiment with such cross-fertilizing techniques throughout his career as a filmmaker, always breaking new ground both stylistically and dramatically.

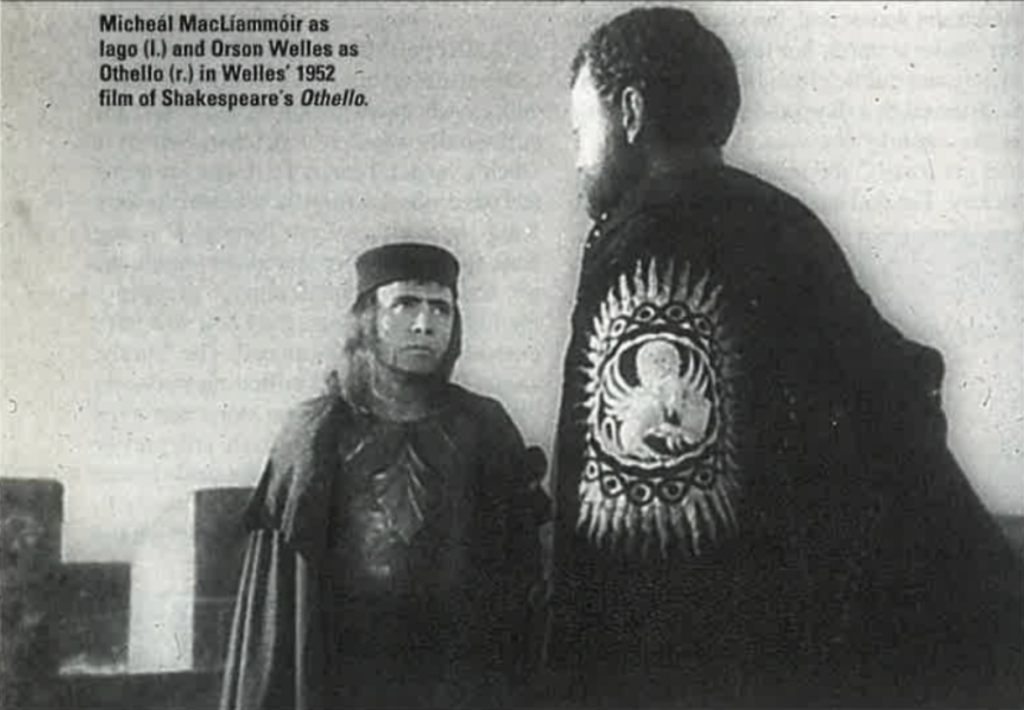

MacLíammóir played a chilling Iago in Welles’ 1952 film of Shakespeare’s Othello and chronicled the seemingly endless filming process in his droll 1952 diary Put Money in Thy Purse, which Welles hurled across a room when he read its irreverent account of his youthful cheek. But to reciprocate the help he received on Othello from both MacLíammóir and Edwards (who played Brabantio), Welles appeared as himself in the only film Edwards directed, the 1951 Gate Theatre short Return to Glennascaul.

Reissued by MPI Home Video in 1994 as Orson Welles’ Ghost Story, this pleasant cinematic curio, filmed in Ireland, demonstrates where it was that Welles acquired his penchant for dramatically expressive lighting.

Welles’ final theatrical venture in Ireland was his 1960 co-production with Edwards of Chimes at Midnight, a forerunner of his great 1966 film based on Shakespeare’s cycle of plays about Falstaff and Prince Hal. A misunderstanding with MacLíammóir, who somehow had been under the impression that Welles wanted him to play the young prince, caused a rift in their friendship. The production itself was something of a fiasco, closing prematurely after it moved from Belfast to Dublin’s Gaiety Theatre.

Welles staged a touching and hilarious reunion with Edwards and MacLíammóir in his last completed film, the little-seen 1978 documentary Filming “Othello.” The viewer has the rare privilege of eavesdropping on a dazzling conversation among three flamboyant old masters of the theater as they debate the meanings of the play and how it should be staged and filmed. Spirited as youngsters and brimming with ideas about Shakespeare, Welles and his mentors rekindle their old bond of love and friendship. After a friendship spanning more than 45 years, one could easily imagine these three saying, as Falstaff says to his two old cronies, “We have heard the chimes at midnight.”

Editor’s Note: This article was originally published in the June/July 1999 issue of Irish America. ⬥

Leave a Reply