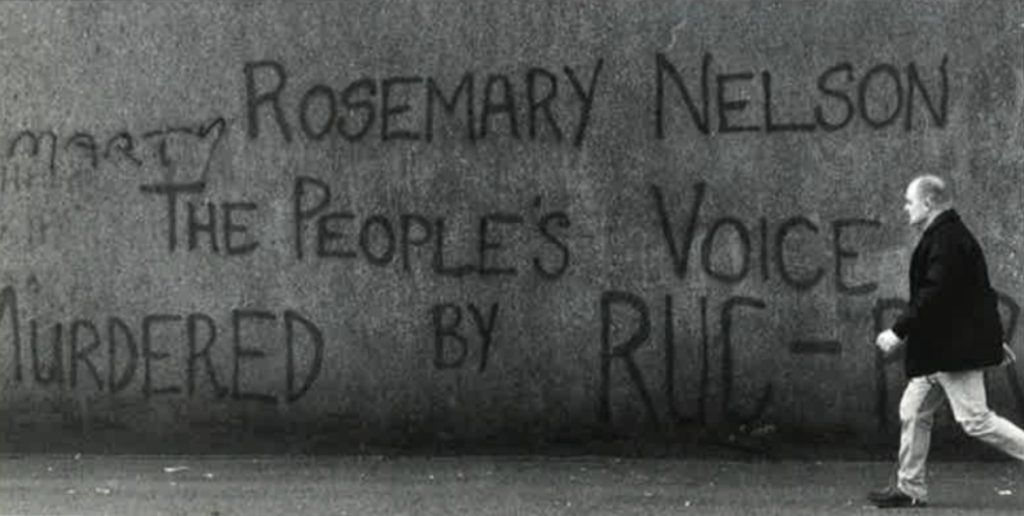

Civil rights lawyer Rosemary Nelson was killed in March by a Loyalist car bomb. Her life and death and what it means to those she represented, including the Garvaghy Road residents, is explored by Nell McCafferty.

Two hours passed before she was officially named but most of those who heard the initial news flash knew immediately who had been killed when a bomb exploded on March 15 under the car of an unidentified woman solicitor in Lurgan, Northern Ireland. It had to be Rosemary Nelson. Women have rarely been targeted deliberately. The IRA had never done so. Loyalists had picked off Catholic women at random when bloodlust was high but the number of women selected by them because of their known politics could be counted on the fingers of one hand — Marie Drumm, vice-president of Sinn Féin, shot in her hospital bed in 1976; Professor Marian Daly, campaigner on behalf of IRA hunger strikers, shot at home in 1981; Bernadette McAliskey, wounded at home in 1981; Sheena Campbell, Sinn Féin law student, targeted while she socialized in a Belfast hotel in 1992.

There has only ever been one high-profile woman solicitor in Northern Ireland. Before she was identified with nationalism, Rosemary Nelson was known as the first woman to set up her own practice in the country town of Lurgan. Ironically, her actual physical profile further enraged her detractors in a militantly male province. The left side of her face was scarred from botched surgery, performed on her as a child to remove a strawberry birthmark. Bad enough that she should step outside the North’s reactionary boundaries for wives and mothers and take up a job; that she should show her scarred face to the world was nearly enough reason to remove her from public life. Long before she was killed, Rosemary Nelson, mother of three, had to endure the rage of loyalists, unionists, police and army about the very way she looked. Scarface, one-eye, they taunted; the only reason she defended IRA men was because they were the only men who would look at her and that only because they had to — because she was one of the few willing to exhaust all legal remedies open to them.

In this latter regard, her detractors were right. Since the campaigning lawyer Pat Finucane was murdered in 1989, lawyers who defend republicans have kept a low profile, cautiously and rigorously ensuring that their briefs began and ended at the courthouse door. Rosemary Nelson, in vivid contrast, defended the interests of her clients all the way to the United Nations. She didn’t just defend IRA related cases. She pursued a vigorous human rights brief on behalf of nationalists who challenged any aspect of the British government’s administration of Northern Ireland. She had testified before the U.S. Congress, accompanied her clients to meetings with British Prime Minister Tony Blair, and taken their cases to the Irish government in Dublin.

Crucially, she had argued British state and security force collusion in the intimidation and murder of Northern Irish nationalists. Among the files which she kept on collusion was one devoted exclusively to herself. She was the solicitor to Sean McPhilemy, whose book The Committee, alleging such collusion, was published last year in America. If what McPhilemy writes is correct, says U.S. Congressman Peter King, “The RUC [Royal Ulster Constabulary, i.e. police], Unionist business leaders and Unionist politicians have carried out systematic human rights violations against Northern Irish nationalists.” King advises President Clinton on American policy towards Northern Ireland. Nelson was in possession of McPhilemy’s files. She was scheduled to open them in testimony before Congress last month. The bomb which killed her was far more sophisticated than the crude devices hitherto available to the Red Hand Defenders which claimed the assassination. The North’s deputy First Minister in waiting, the nationalist Seamus Mallon, who shares power with unionist First Minister in waiting, David Trimble (named as a close associate of members of The Committee), immediately declared that “shadowy forces” were behind the bombing of Rosemary Nelson. The Irish government subsequently joined with Northern nationalists in calling for an independent inquiry.

Thus far, the RUC — which Nelson had accused of making death threats against her — has maintained control of the investigation into her death. In its first appeal for local information to help with inquiries, the RUC gave the wrong date for her death and provided an operational telephone number which had been disconnected twelve months ago. A previous internal inquiry into her allegations of RUC death threats had to be taken out of the hands of the police force when the Independent Commission for Police Complaints established that police officers “showed hostility, evasiveness and disinterest” and “displayed ill-disguised hostility to Mrs. Nelson.”

The results of the inquiry have yet to be published but the United Nations were sufficiently convinced of the threats to her life to place her name on an international list of lawyers believed to be at risk. UN investigator Dato Param Cumaraswamy concluded in a report issued last month that there was some truth in the allegations made by thirty lawyers that they were not getting any response from the RUC about intimidation against them from within the force. The police showed “complete indifference” he found, dismissing the excuse offered by RUC Chief Ronnie Flanagan that none of the lawyers had complained directly to him. Ironically, Ronnie Flanagan told Cumarawamy that he could not guarantee the safety of named lawyers who had testified to the UN about RUC threats and their names had to be excised from the UN list of witnesses. Rosemary Nelson was the only lawyer to go public.

Shortly after her death, a verdict was announced in a case with which she had concerned herself, that went to the festering heart of the problem in Northern Ireland. Robert Hamill, a Catholic, had been kicked to death by Protestant loyalists in the town center of Portadown, in full view of the RUC. The judge accepted that the RUC had been warned in advance that Hamill faced danger from a crowd of hostile loyalists; was unable to resolve the question of whether the police had remained in their landrover while the 25-year-old father of two was killed in their sight; found it “strange” that no follow-up action was taken by the officer who arrested and then released one of Hamill’s assailants; cleared one assailant of murder because of insufficient evidence and sentenced him to four years in prison on the minor charge of causing an affray. Charges against five other men were withdrawn for lack of any evidence, though the RUC were present throughout the killing.

Rosemary Nelson had been planning a private prosecution against the RUC officers who sat in their jeep a mere fifteen feet from where Robert Hamill was being kicked to death. His family had gone to the Lurgan solicitor after failing to find a lawyer in Portadown who was willing to confront the police.

Portadown has been described as the Alabama of Northern Ireland: the minority Catholic population there considers itself under siege by the majority Protestant population, which in turn reveres Portadown as the cradle of Northern Protestantism and its representative, the Orange Order, and the last British redoubt against a united Ireland. Portadown is synonymous with the annual siege there of Garvaghy Road, an event now televised world-wide every July, when Protestant Orangemen attempt to march through the Catholic ghetto on their way home from worship at Drumcree Church. Sometimes, the police force a way through for them; sometimes the police stop them marching; it all depends on prevailing British government policy. The march is invariably accompanied by widespread rioting, destruction and death.

Nelson was also the lawyer for the Garvaghy Road Residents Coalition, masterminding their legal attempts to have the annual Orange march blocked, advising them on tactics for resolution of the conflict which would involve dialogue between the two opposing groups. Orangemen have steadfastly refused to talk to the Catholics, most infamously in 1996, the year before Hamill was killed. In 1996, after the march was banned by the British government, thousands of Orangemen brought the North to the brink of disaster by gathering in force at Drumcree Church and threatening warfare against the RUC and British army if they were not allowed down Garvaghy Road. The stand-off, which lasted for six days, was led by David Trimble MP, member of the Order, Ian Paisley MP, leader of the militantly Independent Orange Order, and Billy Wright, otherwise known as “King Rat,” the most feared sectarian killer in the North and leader of a Protestant paramilitary group, the Loyalist Volunteer Force.

During those six days, loyalists and Orangemen throughout the North showed solidarity by blockading roads, ports and the airport, and closing down places of work. They were supported by Unionist politicians. Catholics were burned out of their homes, a Catholic taxi-driver was murdered, and a leaflet was circulated which stated that Rosemary Nelson, prominent in defense of the Garvaghy Road Catholics, was “a former bomber…without a future.” She said at the time that she was “aware that the RUC have copies of this leaflet but they have yet to inform me of this threat to my life.”

The British government yielded to pressure, the Orange march was forced down the Road and Trimble and Paisley were televised as they did an infamous victory jig together. Within months, Trimble was elected leader of the majority Ulster Unionist party. In 1997, after Robert Hamill was kicked to death, the RUC corralled residents into their homes on the Garvaghy Road while the Orange Order marched down the road once more.

In 1998, following peace talks and the Good Friday Agreement between David Trimble and Gerry Adams, the march was banned. Though he stayed away this time, an Orange siege similar to that originally led by Trimble was mounted, and the mobilization collapsed only after three Catholic children were burned to death during an arson attack on their home. The Orangemen, however, have since retained a token presence on the hill at Drumcree Church, and have kept their promise to camp there until the march should go down the Garvaghy Road in July of this year.

Every evening since last July, the Orangemen have mounted protests on the hill, confronting police and soldiers, and the protests have been augmented by similar daily demonstrations in Portadown town center. The result is that the Catholics of Garvaghy Road, fearful of meeting the same fate as that of Robert Hamill, have spent the last year confined to their ghetto. Their dread was confirmed when Rosemary Nelson was killed. She was their adamant public defender. No lawyer has come forward to represent them now, though many lawyers and the members of the judiciary turned up at her funeral. The human rights campaign is simply not worth the risk to their lives.

The Garvaghy Road Coalition candidly acknowledges that in the absence of Rosemary Nelson, they have become weakened pawns in a political game. A solution to the annual siege must be found this year if a proposed power-sharing Executive between unionists and nationalists is to succeed. Though the British government will retain control over the RUC and British Army, Gerry Adams and David Trimble cannot credibly preside this year over a confrontation between their respective tribes in Portadown which would see the RUC enforce the rights of one side over the other. The Orangemen have threatened to bring the entire order — one hundred thousand brethren — to Drumcree if the local march is banned again. At the time of writing, they have still refused direct talks with the Coalition, a point on which Nelson was fiercely insistent, citing human rights precedents. Ironically, in her absence, Sinn Féin, which has been pressing pragmatically for a compromise, will find more room for maneuver.

On the other hand, if the IRA yield to the Unionist demand for decommissioning of weapons as a condition of Sinn Féin entry into the Executive it is expected that the quid pro quo will be another ban on the Orange march — unless Trimble can persuade the Orangemen to compromise. Trimble, a lawyer himself, and parliamentary representative of Portadown, has so far refused to meet members of the Coalition, who are among his constituents. Should he finally agree to do so now, it will be over the dead body of his opponent, the lawyer Rosemary Nelson, it has been bitterly noted. And, at that, only because she is dead, a thorn removed from the side of the establishment?

Editor’s Note: This article was originally published in the June/July 1999 issue of Irish America. ⬥

Leave a Reply