Her trademark blue fiddle makes her stand out on stage, but it is when Eileen Ivers starts to draw her bow across those strings that she gets her biggest response. Her latest album draws from all her musical experiences, from Riverdance to a distinct South African influence.

A huge cheer of recognition goes up from the large crowd gathered to hear Eileen Ivers and her band at the Bowery Ballroom in Manhattan recently. Much like B.B. King has become synonymous with his guitar, “Lucille”, Eileen Ivers is becoming inextricably linked with “Ol’ Bluie,” her dazzling bright blue electric fiddle.

And what an impressive swath she’s carved out with that blue fiddle. From Green Fields of America to Cherish the Ladies to Hall & Oates to Riverdance to the Boston Pops to her own band, Eileen Ivers has made a career of breaking down musical stereotypes. Just listen to her latest album, Crossing the Bridge, her first on the Sony Classical label. It’s a virtual travelogue of musical interests — Ivers incorporates influences from Africa, Spain, and the Caribbean into her songs — but ultimately, she’s true to Irish traditional music, true to her heart.

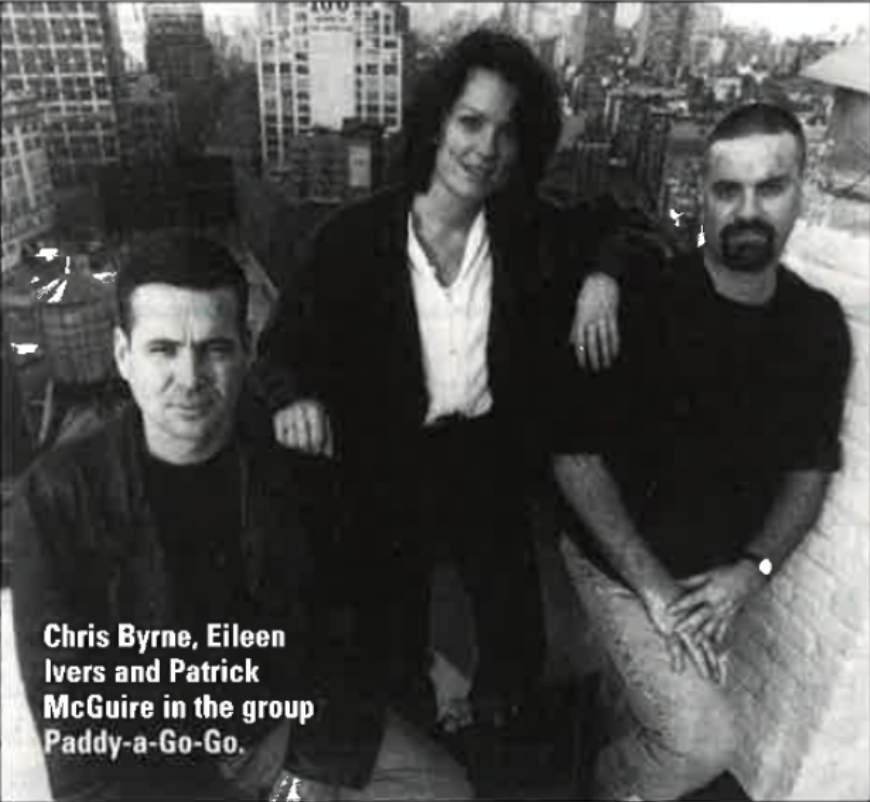

According to Ivers, the music on Crossing the Bridge is simply an extension of her own varied musical tastes. “I knew I wanted to make this kind of record,” she states, “because of the things I’ve been doing for the past few years. Latin music, Riverdance, Paddy-a-Go-Go (a hip-hop project she played in a few years back with Black 47’s Chris Byrne and singer Pat McGuire) — these are all things I’ve been involved with and have rubbed off on me. And I’ve always loved the sound of South African vocals, they’re just so soulful. So I knew I wanted that sound on the record too. But you’ve got to be true to your roots as well.”

She is. Though the tracks on Crossing the Bridge are marked by stellar players from all corners of the earth — guitarist Al DiMeola, bassist Bakithi Kumalo, drummer Steve Gadd, and percussionist Alex Acuna all make guest appearances — there’s still space carved out for the traditional. “There’s an air on the album, called ‘Dear Irish Boy,’ that I’ve been playing for years,” says Ivers. “In a lifetime you don’t get to play that many airs. Airs to me are the real soul of Irish music. So you’ve got to be respectful.”

Eileen Ivers’ respect for the music came at an early age. Born in the Bronx in the mid-sixties to emigrant parents from Mayo, Ivers was steered towards Irish dancing by her mother. “I took dancing lessons for all of two weeks. I was so bad. I hated it,” Ivers recalls, laughing. She instead took up the fiddle — inspired by the TV cornball comedy show Hee Haw, of all things. “I was about eight years old — I saw someone playing a red white and blue fiddle, and knew immediately that’s what I wanted,” Ivers recalls. Her mother wasn’t thrilled. “Ah no, Eileen, try the piano instead, it’ll be lovely,” Ivers says of her mother’s reaction to Eileen’s fiddle request.

But Eileen prevailed, and was sent to noted Irish music teacher Martin Mulvihill for lessons. It proved to be a watershed event in Ivers’ life. “I have such fondness when I think of Martin,” says Ivers of her late teacher. “He was selfless. He did so much, bringing music to so many children. He’d go out every weekend to a different borough on the subway to teach. It was rough for him. I truly wish he were here today.”

So under Mulvihill’s tutelage, Ivers practiced — and practiced some more. “I was awful in the beginning. Just wicked,” Ivers says, but it’s a notion that’s hard to comprehend. “I’d be squeakin’ and squawkin’ away,” she says. All-Ireland competitions and medals followed during summer trips to Ireland. “Though the idea of a music competition is a little strange to some people, the competitions were a real incentive to get better,” Ivers explains. “I didn’t want to embarrass myself — or Martin,” she says.

In those formative years it was all about playing, repeating, absorbing. “You’d play at house parties. You’d play at dances. You’d listen to those old mono records, go back to the great masters and learn every technique. You had to.” As she grew old enough, she started playing paid gigs, as well. Ivers was pursuing a degree in mathematics from Iona College, while playing on weekends. “There was no better education than pub gigs, those hard four hour gigs. Learning how to play those ugly keys, B-flats and F-sharps. It was the best experience ever.”

It was right after college that music started to take off for Eileen Ivers. She began playing on other traditional artists’ records, and soon thereafter hooked up with Mick Moloney and Robbie O’Connell on the Green Fields of America project. “I remember watching Mick and Robbie on stage, they were such pros — they taught me so much about professionalism, about protocol, about acknowledging other players on stage. I would have never known about all that if not for them.”

Around the same time, Ivers struck up a friendship with bassist/producer T. Bone Wolk, who was playing with Hall &Oates. Wolk approached Ivers to contribute a track or two to a Hall and Oates record — which led to a slot with the touting band. Ivers traveled around the world with Hall & Oates; an experience she recalls fondly.

“It was like I was taking another musical degree,” Ivers explains. “They’d play all these great records in the back of the bus. I learned a whole other style of music, the whole R&B blue-eyed soul thing.”

Ivers learned about the rigors of the road as well. “We toured the states for six months, and let me tell you, it was rough. We went from the gig, to the bus, to the hotel, to the sound check, to the next gig. The guys would rush onto the bus and say `this one’s my bunk, this one’s mine.’ Hey, I didn’t know. So of course I got the bottom bunk over the bus wheel,” she laughs. “The first week, I thought I was going to die.”

She didn’t, of course. Ivers went on to record with the likes of Luka Bloom, Patti Smith, Black 47, and Paula Cole. She, along with Joanie Madden, was a founding member of the trailblazing all-women group Cherish the Ladies. She also contributed her formidable talents to experimental groups Eo and Paddy-A-Go-Go. “Paddy-A-Go-Go was such a neat time in my life,” she explains. “The concept was to combine a rap thing with dram loops and a traditional instrumental influence — more of a New York sound of today, rather than — these are Chris Byrne’s words — some boating accident in the 1700s off the coast of Connemara that we knew nothing about. Seriously though, Paddy-a-Go-Go was very much about the modern Irish experience in America.”

But it was the call from producer Bill Whelan that brought international acclaim to Eileen Ivers. Ivers was a featured soloist on Riverdance, and wowed crowds the world over with blazing lines from her blue fiddle. Riverdance opened her eyes — and ears — to new ideas as well. “It was during Riverdance that I started to think about incorporating dance steps into my own music,” she explains. “Maria [Pages, the featured flamenco dancer in Riverdance] and I worked together for three-and-a-half years. The things she would do with her feet were unbelievable. I knew that vibe-wise, those flamenco influences would mix well with Irish music. And Tarik [Winston, Riverdance tap dancer] is this twenty-one year old guy from the Bronx who does the most amazing things — he’s on the album as well.”

The nineties are peppered with even more accomplishments: an appearance with the Boston Pops, three highly acclaimed solo albums on the Green Linnet label, a guest artist slot on the most recent Chieftains tour.

But despite the dizzying accomplishments, Ivers remains remarkably down to earth. “I’ve learned as you get older that you don’t take for granted where you are, and the people you’ve played with,” she says.

“You’re learning, you’re growing, you’re moving forward — but the music has got to reflect where you are in your life.” Ivers is at an exciting point in her own life — she’s making plans with fiancé Brian Mulligan for a fall wedding.

So where did you get that blue fiddle, Eileen? “I was walking along 48th Street (a strip of music stores in Manhattan) and I just saw it in the window,” she recalls. “Maybe the Hee Haw thing came back to me, I don’t know, but I just knew I had to have it,” she laughs.

She didn’t just get the fiddle — she bought a slew of effects pedals as well. She remembers the sales pitch well. “The sales guy in the store said to me, (affects goofy slacker voice) `Hey man, wouldn’t a wah-wah pedal be really cool with that?'” she recalls. “I had no idea that Jimi Hendrix had used one, but I just fell in love with the sound of it.”

Wah-wahs, phase shifters, delays — Ivers has embraced them all. “The electric fiddle is definitely a different beast than the acoustic,” Ivers explains. “I went crazy.” Often to the chagrin of Joanie Madden, especially in the early days. “Joanie would say to me, `If you play that (makes cat sound) weow-weow-weow thing one more time, I’m going to kill you.’ But you have to overuse them, to learn how to use them,” she says.

But will the wah-wah pedal and blue fiddle fly in the halls of Sony Classical, her new label? “The beautiful thing is that I was really allowed to make the record I wanted to make,” says Ivers of her new label bosses. “There were no constraints.”

Her experience playing with the Boston Pops Orchestra also shattered tradition. “They actually wanted me to play electric fiddle, with some effects,” Ivers recalls. “So I did — and I was petrified. Half the string section loved it — the other half thought it was disgraceful,” she laughs. “But it was a learning experience.” Now that she’s with a classical label, Ivers may try her hand at an orchestral piece in the future. “That’s definitely something I’m interested in pursuing. I’m not a great [music] reader, but I’m trying to get better. And I’m really getting the bug for writing. I wrote about half the songs on Crossing the Bridge with [producer] Brian Keane. We’ve talked about doing an orchestral record down the road.” Orchestral, African, Flamenco, Caribbean, Hip-hop — it’s all on Eileen Ivers’ radar. As far as she’s concerned, there are no dividing lines.

“There are so many ways to express violin music, Irish music, fiddle music,” she states. “I’m always into challenges, into learning, into getting better at different things. If the music takes me in that direction, I love to go there.”

Editor’s Note: This article was originally published in the June/July 1999 issue of Irish America. ⬥

Leave a Reply