Raised between the U.S. and his parents’ native Ireland, Aidan Quinn had the best, and worst, of both worlds. It’s an experience that has served him well, however, when it comes to his acting. His latest movie, a family affair, involves all but one of his siblings, and is truly an Irish tale.

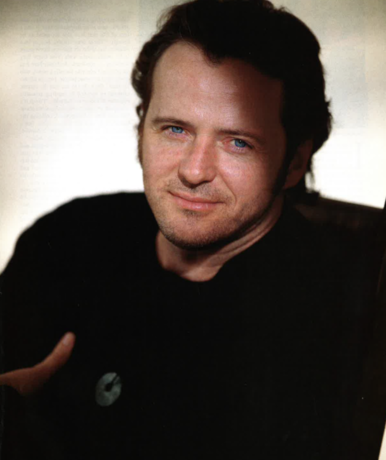

If Aidan Quinn were any more laid back he’d be horizontal. He’s just lolled his way through a two-hour photo shoot, and is now sprawled on the other side of a tiny table in a charming old bar on Manhattan’s lower west side. Clearly savoring the large cigar he’s sucking on contentedly, he’s turned sideways in his chair, lazily surveying the Friday afternoon stragglers indulging in a spot of late lunch.

Maybe it’s the fact that the weekend is fast approaching, or because he’s currently enjoying a well-earned rest between movie projects or maybe it’s just because he was out late the previous night, but he’s the very picture of languor. Questions are batted off with a lazy hand, and pondered in a haze of pungent cigar smoke as he gazes off to the distance before laconically drawling out a considered reply. Talking about his many movies (23 in fifteen years) doesn’t excite him nearly as much as when he gets started in on his passion for nature and the environment. Oh, and Ireland, of course. “Oh, I really want to do a movie in Ireland again,” he exhales with a deep groan. “That’s how I get to spend time there…months.”

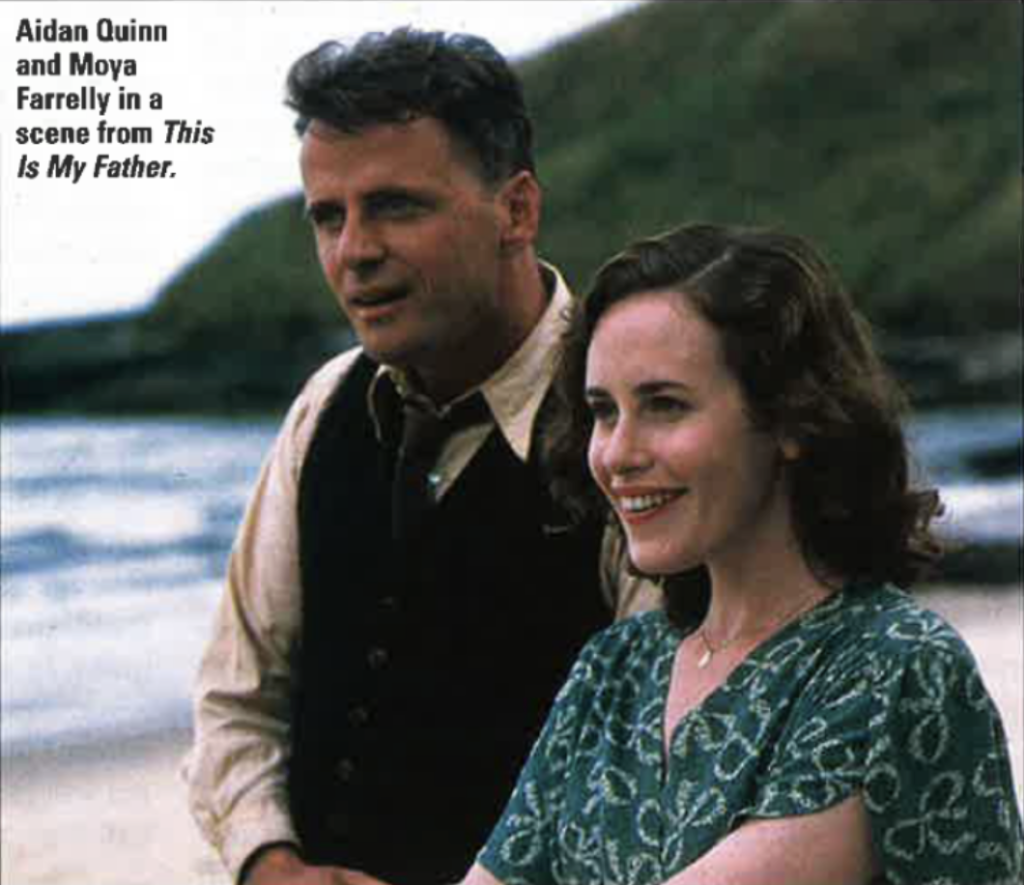

The fruits of his last extended period spent in Ireland, two years ago, resulted in a moving film called This Is My Father, a labor of love in more ways than one. Written and directed by Aidan’s younger brother Paul, inspired by a story their mother Teresa told them as kids, filmed by older brother Declan and starring Aidan as a shy, unsophisticated country farmer and his sister Marian as one of the sniping local women, the movie recently opened in the U.S., having already played to great acclaim in Ireland.

Shot on a small budget, and filmed on a very tight schedule, with the three Quinn brothers acting as co-executive producers, along with their equally demanding other roles, the movie was an “exhausting but great” experience, according to Aidan. “There was always some crisis,” he laughs ruefully, “it was a lot of hard work.” Later this summer, he’ll also be seen in 50 Violins, in which he plays boyfriend to high school music teacher Meryl Streep.

Since he was first cast back in the early 1980s as the rebel biker renegade who stole Daryl Hannah’s high school heart in Reckless, Quinn has appeared on movie screens in a variety of incarnations. A theatrical charmer in The Playboys, Harry Boland to Liam Neeson’s Michael Collins in the movie of the same name, a missionary in At Play in the Fields of the Lord, a man fighting with his brother for the love of the same woman in Legends of the Fall — the two constants have been those bluer than blue eyes. But even they disappeared behind brown contact lenses when Quinn played Carlos the Jackal in 1997’s The Assignment. That, he readily admits, was one of his favorite roles, and a welcome departure from what he calls the many “snack parts” he’s offered. He is aching for a shot at more meaty roles, the ones that would shoot him firmly onto that coveted A list, but says he also tries his best to spend six months a year at home with his wife of twelve years, actress Elizabeth Bracco, and daughters Ava, nine, and Mia, 12 months (“we’re working our way through Frank Sinatra’s wives,” he jokes). They split their time between their home in New Jersey and a 200-year-old stone cottage in New Falls in upstate New York. “And some day,” he muses, “I’m going to find a place, a tiny little place in Ireland.”

It was a very different story when Quinn’s parents announced to their brood in 1972 that they were moving back to Ireland from suburban Rockford, Illinois. Ireland, he says, was the last place on earth he wanted to live at that time. “My whole life started when I was 13,” recalls Aidan, who turned 40 in March. “I didn’t want to move back to Ireland, I was like, `Oh no — no football, no baseball…all my friends,’ but the minute we got there, within a week, I was so in love with it.”

His Mayo-born, Offaly-raised father Michael was on sabbatical from his teaching position, and he and wife Teresa decided to head home with their kids, Declan, Aidan, Paul, Robert and Marian. It wasn’t the first time the kids had been in Ireland, they had shuttled back and forth on a fairly frequent basis, and his mom had brought the older kids back to live there for a year when Aidan was three. “Declan is really more Irish than he is American because he went through secondary school there,” remarks Quinn. “From the age of 12 to his mid 20s, he was in Ireland. The same thing with my sister, she was sent back to live with an aunt and uncle when she was 12. They would come home for summers.” He describes himself as being somewhere “in between,” having racked up about five years of Irish life. Paul spent about three years in Ireland, and the youngest, Robert, has spent most of his life in the States. “We go from being American to really Irish in the same set of siblings,” remarks Aidan. Teresa, a native of Cloghan, Co. Offaly, near the Bog of Allen, acknowledges those early years as being difficult. “We had one child after another,” she recalls. “It wasn’t easy, it was rough…we had very little money and it was hard, it really was. But we did manage to get back to Ireland a lot, even though we couldn’t really afford it.”

Like many immigrants at that time, the young couple had never really intended to stay in the United States. Michael recalls leaving Ireland, immediately after they married, with the idea of returning home after two years. They came first to Canada, where he taught in London, Ontario. After a year there, they moved to Chicago, where all of the kids were born.

On arrival in Offaly in the summer of 1972, the exotic Americans stood out. Declan had already lived in Birr and paved the way for his siblings, introducing them to the kids he had made friends with. Instant friendships were struck up, without the usual awkward adjustment period, and Aidan soon found himself a huge hit with the girls. After the summer was over, it was off to Dublin for the Quinns, who lived in Deansgrange for the academic year.

School quickly proved to be one of the biggest adjustments. Having been used to public school in Illinois, Quinn found the Christian Brothers in Dublin a big change. “I just couldn’t believe that they could just walk up to you, hit you with the leather and the cane, and get away with it,” he laughs incredulously. “Here they’d be sued, you know.” The recent spate of pedophile abuse cases involving Irish religious brothers and priests came as no surprise to him, it was a fact of life that was just accepted as he recalls. “There was always one or two brothers out of the six that you knew never to be caught alone with. You knew they would try…you know. And then there was the principal who was literally a sadist, who really liked to torture people. He was a hateful man.” He’s glad to see that the current climate in Ireland is leaning towards exposure of such evils, but adds, “I think it’s also good to make some realizations about that and how it happened. Confining the human body and the human spirit, that’s unnatural. It creates aberrant behavior, because it has to come out somewhere.”

A year later, the family uprooted again, and headed back to Illinois. “That was just awful,” he says. “Because I had just had this explosion of life and being accepted and wildness and girls and then we came back into this suburban community where I was…some odd little Irish American kid. Because our parents `talked funny,’ they used to call us foreigners.” The childhood taunts only served to strengthen the bond between the Quinn siblings, but the sense of being outsiders never quite left, a factor he thinks is partly responsible for the strong creative streak running through the family. He and Marian are the actors (she has also written a film script, a first bras/first boyfriends teenage movie set in Dublin), and Paul also dabbled in some stage and movie work before ultimately turning his hand to writing, and more recently, directing. Declan is the eye behind such screen gems as Leaving Las Vegas and Kama Sutra, and Robert, the youngest of the brothers, is a landscaper in Rockford, not to mention a great artist, according to Aidan. “I think [the creativity] probably came from that living back and forth,” he muses, “because we were observers of both places, we were slightly detached. Maybe that’s it, I don’t know.

“It’s a terrible cliché, but it’ s a blessing and a curse, it really is,” he says of the duality in his upbringing. “You’re a bit of a stranger in a strange land in both places, but on the other hand I wouldn’t trade it for the world.” His sister Marian, he notes with a laugh, always swore she would never do the same thing to her kids, but she, her husband and two sons live between Brooklyn, New York and Dromahair, Co. Leitrim. “I talk to [the boys] on the phone and I swear to God they have Brooklyn-Leitrim accents,” laughs Quinn. “One word is Brooklyn, the next is Leitrim, and it’s the oddest mix. So it’s happening again!”

Once back in Illinois, the teenage Aidan discovered that sports were a great way to be accepted, and he duly threw himself into athletic pursuits. He also headed to Ireland for summers, hitchhiking around the countryside when he was 16. After finishing high school, he was back again, this time for a year. He lived in Dublin, but found it a lonely experience, with his friends spread outside the city. “I was basically just wandering around reading Yeats and Joyce and wanting to be a writer,” he recalls with a grin. “I’d go into Stephen’s Green in the middle of the night, climb the fence and sit up in the tree and I’d talk to myself and scribble poems, and just fantasize.” Explains his father, Michael, “They were surrounded by books as kids so it might have been just a natural osmosis type thing… we always tried to encourage them to read.”

Part of Quinn’s artistic exploits in Dublin involved taking in some lunchtime theater at Trinity College, something his parents had done during their sabbatical year in the city. When he returned to the States at the age of 19, he worked as a hot tar roofer before trying his hand at acting. A stage debut in Chicago (where brother Paul later co-founded New Crime Productions with John Cusack, Jeremy Piven and six others) was soon followed with a role in an off-Broadway production of Sam Shepard’s Fool For Love. Then came the James Dean-like role in 1984’s Reckless, and Quinn was launched in Hollywood.

His onscreen leading ladies to date have included Madeleine Stowe (Blink), Julia Roberts (Michael Collins), Sandra Bullock (Practical Magic), Robin Wright Penn (The Playboys), Sissy Spacek (The Stars Fell on Henrietta) and Annette Bening (In Dreams), but with movies like The Mission, The Handmaid’s Tale and Avalon, Quinn has managed to avoid being fully typecast as the fuzzy, male romantic lead. The Assignment proved to be one of his biggest challenges to date, but the movie underperformed at the box office. In the movie, Quinn played legendary Venezuelan terrorist Carlos the Jackal, and doubled up as U.S. Navy lieutenant Annibal Ramirez, a dead ringer for Carlos who is used by the CIA and Israeli intelligence as a foil for the Jackal’s operations. It remains one of his favorite roles to date, and he sees it as a vast improvement over some of the other parts he’s been offered. “I’m a little tired of these snack parts,” he says forcefully. “I need parts like The Assignment and [This Is My Father] to make me feel challenged and engaged.” He agrees that star power often results in being pigeon-holed character-wise, but adds with a somewhat humorless laugh, “I wouldn’t mind having a shot at that dilemma.” At the same time, he admits to having turned some roles down to be with his family, and the regrets, he says, are few. “Otherwise you’re going to sit on your deathbed going, `Gee, I never saw my kids grow up.’ It’s not worth it.”

[Leaving Ireland] was just awful. I had just had this explosion of life … and then we came back into this suburban community where I was an odd little Irish American kid. Because our parents ‘talked funny,’ they used to call us foreigners.”

One of the parts he is rumored to have turned down was that of Christy Brown in My Left Foot, the role which ultimately won actor Daniel Day-Lewis an Academy Award. “Hmmm,” drawls Quinn, “it’s not strictly true, I didn’t exactly turn it down.” This, he says, is the way he recalls things (“but you know how memory is,” he adds): director Jim Sheridan asked him to do the part, and then Noel Pearson came on board, but the duo had problems raising the necessary cash. Quinn told them he’d have to spend at least a month in hospital with cerebral palsy sufferers, a theory Pearson pooh-poohed. The next thing Quinn remembers, Sheridan came back to tell him Day-Lewis was interested and could bring a couple of million pounds to the financing. Quinn told them to go ahead. “I never resented it,” he avers. “I thought Daniel Day-Lewis was brilliant and I thought he did the role the only way you can do that role. I was very happy for him.” It’s not, he hastens to add, that he never gets burdened down with jealousy or envy (“I’m very human” he promises), but rather that he tends to accept those emotions for what they are and move on with his life.

He and his wife have never worked together, but he thinks she might be coming around to the idea. (He refers to her often, jokes that she has “veto power” in his life. Asked how many children he’d like to have, he replies, “Well, my wife says we’re done, so…two.”) Their close friends include Stanley Tucci (Big Night, The Impostors) and Steve Buscemi (Trees Lounge), two actors who turned to writing and directing themselves in a bid to “create work that was worthy of their talent,” according to Quinn. He can see himself in a place (“if my life ever slows down enough,” he laughs) where he might turn to writing, directing (“the hardest job in the world”) and producing. He’s even contemplating a return to his stage roots.

One thing that continues to annoy him, however, is the fact that he has never (a word he emphasizes) landed a role through the audition process, all of his movie parts to date have been offered to him. He’s not sure why but thinks it has something to do with the fact that most of the studio heads have already made up their minds as to which A-list male star they want for the role. “And I don’t do too well in auditions,” he adds, “I get nervous and it doesn’t bring out the best in me. I don’t audition very often, it’s only when I really want something.”

One of the roles that he really, really wanted, and which he didn’t have to fight for was the part of Kieran O’Day in This Is My Father. Quinn is introduced about a quarter of the way into the movie, when the action flits back to 1939 and a vivid slice of rural Ireland as it was then. James Caan plays Chicago high school teacher Kieran Johnson, the modern-day American tourist who journeys to Ireland to find out about his mother’s past, and hopefully in the process discover something about the father he never knew. He meets an old traveler woman who knew his vivacious young mother Fiona, and the story begins.

Fiona Flynn (played by Moya Farrelly) has been kicked out of school in Galway, and has returned home to live with her widowed mother, scandalizing the locals who regard her as a loose woman. When she takes up with Kieran O’Day, almost 20 years her senior, the villagers are doubly appalled and what starts a sweet love story soon turns to tragedy.

Teresa Quinn laughs when she’s asked how she felt about Fiona’s character having been based on her. “I wasn’t that wild, I don’t think,” she says. “I was full of life, loved to go dancing and all of that. I enjoyed my youth.” She also used to daydream, much like Fiona, about one day living in a place where there were skyscrapers.

Quinn says it was fun to play with changing the way he looked and walked, even his teeth were blackened and his nails barely visible under the dirt. “I feel like I knew that man,” he says. “I know the farmers, I know them from my mother’s family and from around Birr and out in the Bog of Allen… so it didn’t take an awful lot of research. The only thing I had to work on was the accent.” That, he readily admits, was quite a challenge. For The Playboys, his first `Irish film,’ he was under the impression that aping his parents’ Offaly twang would have presented no problem, but the first day on set soon banished that cockiness and he settled down to work with a dialect coach. The same coach helped him through Michael Collins a couple of years later.

The days on set were long, a race against the clock to get the film wrapped on time. Cast and crew often worked up to 18 hours. “We hadn’t spent that much time together since we were young kids,” laughs Quinn. “Luckily we mostly get along, but there’s always a certain tension working with family.”

For Paul, that tension emerged as he readied the set for Aidan’s first scenes. “He was giving a lot of directions here and there and my first assistant director was a little worded, freaking out, `Your brother’s going to take over the shoot!'” he remembers. “Fortunately I talked to his hair guy, who had worked with him on three or four films and he said, ‘Oh, Aidan’s always like that on the first day, everybody relax.'”

Did Paul find that he had to restrain his directorial impulses, given that he was working with his older brother? “Well I didn’t even have to, Aidan just wouldn’t take it,” he laughs, speaking over the telephone from his home in L.A. “I’d say, `Aidan, you know that line, the way you say it?’ and he’d go (mutters), `Yeah, yeah, I know, I know, I know,’ and that would be the end of it.”

One thing Aidan worries about is that many people will identify too readily with what he calls “the strong anti-Church statement” running through the movie. Stephen Rea and Eamonn Morrissey are the two holier-than-thou priests in This Is My Father, with Rea in particular bringing the hellfire and brimstone act marvelously to life. (One scene, involving some confessional dramatics had the audience howling with laughter at a recent screening in New York City.) “I think there’s an over-reaction in a lot of young people,” he muses. “I see them going completely the other way until they don’t believe in anything. It’s very important to have a spiritual life. I think it’s everything really, and can be a tremendous comfort to everyone if they can avail of it in a full, loving way, not in a dogmatic, judgmental way.”

For him, nature and the great outdoors are as close to spiritual as it gets (“I’m not an indoor person; when I’m indoors for too long I start to get cranky and miserable, and I’m not fun to be around,” he notes), and his face lights up when he talks of some of the places he’s gotten to visit through his various movies — Kenya, Brazil, Canada and much of Europe. He’s saddened, though, that the rapidly improving Irish economy has left little room for conservation. “What’s so special about Ireland — the countryside and the open spaces — is just being destroyed by slurry pits and a disregard of basic environmental standards,” he says. “To me it’s very important.”

Another thing that bothers him is what he refers to as “the McDonaldization of Ireland.” He says he hates to sound like a bitter, old traditionalist, but does miss the fact that many of the rural regions are becoming Americanized. “You can go off into the back of beyonds in Cavan now and a local kid will have spandex surfer wear and baseball cap turned backwards.” A wickedly funny mimicker of accents (he adopts whichever brogue is appropriate for the anecdote he’s telling at any given time), he also laments the way Irish accents are subtly changing, and a lot of the thicker, country tones are becoming lost.

As movie stars go, Quinn appears to have somewhat mixed feelings about the fact that his entrance into a public room inevitably turns heads. At a recent St. Patrick’s week function in Manhattan, besieged by people who wanted him to pose for photos, his eyes took on something of a cornered look, yet he still graciously smiled for the flashing cameras before making a hasty escape outside to steal a few moments of peace with one of his beloved cigars. Asked how he handles the pressures that fame brings, he equivocates. “You have to deal with it and most people are really nice so that makes it a lot easier,” he says. “But I’m not someone who goes out of my way to seek that kind of attention…and it always seems slightly embarrassing to me when I get it.”

A month after our initial meeting. Quinn hits the big 4-0, but because many of his actor friends are working away, he doesn’t get to have the big birthday bash he’d been anticipating. Speaking over the phone from upstate New York, where he’s been hanging out in his country house, he admits to having some `issues’ with this particular milestone. “It’s funny,” he muses, “I would never have pictured myself concerned about something like that but to be perfectly honest I am. I feel as if I’m re-evaluating everything in my life and wanting to get better roles and looking into producing and directing stuff myself — that kind of thing.” Not to mention, he laughs, the physical changes age has wrought. “My metabolism has slowed down and there’s a widening girth around my mid-section.” But the little boy who was “always acting the clown,” according to his mother, hasn’t fully disappeared. “On my bad days I don’t act the clown enough,” he concedes, “but on my good days I definitely do.”

Editor’s Note: This article was originally published in the June/July 1999 issue of Irish America. ⬥

Leave a Reply