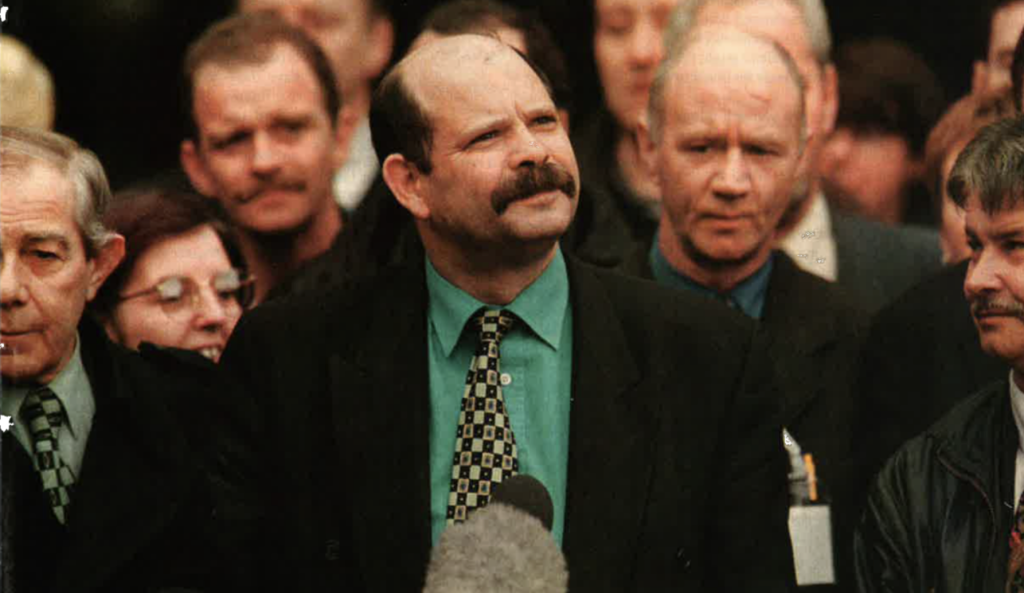

David Ervine, leader of the Northern Ireland Progressive Unionist Party, spoke to the National Committee on American Foreign Policy on April 20 in New York. The focus of his remarks was the peace process now in jeopardy, ironically because the British and Irish governments have pandered to David Trimble, Ulster Unionist leader and First Minister elect of the new Northern Ireland Assembly. (Trimble is refusing to follow the Good Friday Agreement instead insisting that the IRA decommission their weapons before being allowed to take up their seats in the new governing body).

Ervine, 45, a former loyalist paramilitarist, whose party received 3.5 percent of the popular vote, will stand as a European candidate in June. He is a passionate orator who speaks without benefit of notes, and many of those present at the lunch, hosted by Mutual of America, were visibly moved by his remarks. At a time when the peace process is in grave danger of disintegrating, his is a remarkable voice of reason, and compromise. His bravery in speaking out puts him in grave danger from those, including members of his own community, who do not wish to go down the road of change.

What follows is a transcription of his videotaped remarks as edited by Patricia Harty.

I want to thank you for the opportunity for [allowing] a voice, that prior to 1994, had never been heard in the United States, to be heard. We hope that in the hallowed halls of the American administration we do make somewhat of a difference. We hope that we learn and are teachers about Irish America, because when I came here first I had the impression that all Irish Americans were rampant provos [Provisional IRA], but of course that isn’t true. And I was ashamed of my preconceptions and I found that some people in Irish America were slightly ashamed of their concept of what a loyalist or a unionist or a Protestant from Northern Ireland might be, and especially those who were involved in the conflict.

I wish I was here to tell you that things are wonderful at home, and that we will undoubtedly copper fasten to that which was the will of the people, voted for just over a year ago, that which is called the Good Friday Agreement.

I’m not in a position to tell you that in the short term, but in the long term, I can tell you that there will be peace in Northern Ireland, there will be peace on the island of Ireland, there will be peace in the British Isles, and there will be a special, undying relationship or series of relationships built up to replace those that have been consistently fractured over hundreds of years.

The difficulty, of course, is how to move a divided society from the comfort of the tribe to the recognition of the need to be interdependent. How do you convince those who have lived comfortably in the “them and us” belief — them always being bad and us always being good? How do you create the circumstances where people have the capacity to believe that there is merit and benefit in moving out of the covert position of the tribe?

There are three sets of people in any society, at least I assert that that is the case. First, there is the thin band of leadership. Then there is the thick band of moralists, and then there’s the vast sway of everyone else in between. And the everybody else in between is saying to the leaders, can you not do and say the things that make me comfortable and get these moralists off my back?

And that’s what’s happening in the tribes in Northern Ireland.

It isn’t only the political parties that have difficulty in relation to the three strands of people who exist within their organizations, the paramilitaries also have that difficulty.

And as people try to maneuver or engineer or tiptoe their way towards the future — that future not having proven its merit and benefit to the broader populace — the moralists have the opportunity [to discredit that future].

And there are those who are succumbing to the moralists. There are those [leaders] who can’t deliver. And there are those who don’t want delivery. And they are inside both the peace process and the political process, and they are both supported by constituencies. And those constituencies are afraid.

They’re not only afraid of each other in terms of nationalist-unionist, Protestant-Catholic, loyalist-republican. They’re frightened of each other within their own constituencies. They’re frightened that the future may have uncertainties. And that the old certainties may be better lived with than the new uncertainties.

Now how are we going to convince people that it’s worth taking the risk?

In each tributary that you come to in life you’re faced with a decision that patterns the future of your life, and your dependents, and your future dependents. And each time you are faced with those decisions, there is trepidation, there is fear. There is the worry about how you may end up in the future.

In Northern Ireland, we are facing two ways to go. We either go in the direction that we’ve come from, and we know the pain, the sorrow, the injury, the angst, the bitterness, the blood, the sadness that goes along with all that. Or we follow this new vision. This new avenue that you cannot walk up alone. Of course, if Unionism could go up this road on its own, it would be very happy to do so. And if Nationalism could walk up this road on its own, it would be very happy to do so. But we must, absolutely must, manage to do it together.

So, we’re at a tributary. And our people, sadly, perhaps by default, are seriously looking at going back up the avenue from whence we came.

Why is that? How can it be that we were so filled with hope? So filled with the belief of opportunity that we have almost allowed it to slip through our hands?

What are we to do? When the two governments, the moral guardians, refuse — and I emphasize the word refuse — to implement the Good Friday Agreement?

Seventy-one point twelve percent of the people said clearly, YES, I want to go for that vision. I want to go for the new beginning. And the governments, in attempting to pander to individuals, are potentially allowing this process to run into the sand.

[The process] is not about me, it is not about Gerry Adams, it is not about David Trimble. It is about the people of Northern Ireland. And if the two governments [British and Irish] vest, all of their energies and all of their attention, on one individual [David Trimble] that individual’s desires, attitudes and vision of life will be the telling factor, not the will of the people of Northern Ireland.

Two or three years ago decommissioning [of weapons] would have been but a small piece of our discussion. Today, we have created this monster, this cause celebre on both sides, that is about to drain us into the ground. And the constitutional politicians who wouldn’t know a peace process if it jumped up and bit them, must have the proof that the paramilitaries are real [in their desire for peace].

But let me remind you what came first. The peace process came before the political process. One time the politicians attempted to come to terms with the difficulty that is Northern Ireland in round table discussions. The paramilitants were not invited because it was perceived that if the political guys got together, they could work it out. That was in 1991, and they couldn’t work it out. Not only could they not work it out, if they had come out with an agreement, they couldn’t have sold it. There had to be as inclusive a process as conceivably possible to try and move our divided society forward. But I have to say to you, had we been waiting for the politicians in Northern Ireland to create a peace process, we’d be still waiting.

I’m not suggesting that the paramilitants have done us all a favor by allowing us to live and stopping shooting us, that’s not what I mean. But they are wedded, and have been wedded to the brutality and hatred and division that has allowed a war to be fueled. Allowed a war to be driven. And they recognize now that there is no winner in that war. That we’re all losers in that war. And in order to create the space where politics might flourish, they laid down their weaponry, they said there’s got to be a better way. And I concur completely.

It took us a very long time to get a political process together because this one wouldn’t talk to that one, that one wouldn’t sit in the same room as that one. In fact, they wouldn’t even at times go into the same building. But eventually, a political process was created. Now the political process is in crisis. It is in absolute crisis.

Yet what remains intact is a peace process, two cease fires still intact. Does that not say something about the desire? Does it not say something about the will of those people — no matter how brutally you think they behaved in the past — that they have generally recognized the futility of war? They have recognized the need for a new dispensation, a different way to deal with our society, a different way to manage that divided society that is so easily manipulated it can have killers come up like that. Just as I came up like that, as a former paramilitarist, and now a politician.

Am I not entitled to change? Am I not entitled to have seen that being there, doing it [the violence], is no advocacy to my children or my children’s children? Perhaps it took me and others to go there to know that — because I have to say to you that the vast majority of politicians in Northern Ireland never would have said such a thing. They would have moralistically condemned violence, meanwhile ranting loudly and fueling division.

I say, as clearly as I can say, I’m sure you’re bored to tears with Northern Ireland, which has given you many crises after many crises after many crises for the last twelve months. But please don’t lose focus. Because if we ever needed focus, it is now, because we are in danger of losing by default.

If I make a mistake in life, I can live with it, because it was my mistake. But to allow this opportunity to run through our fingers and into the sand, denying the opportunity to our children and our children’s children is unforgivable.

And if you believed in the past that we needed your help, then please don’t think we don’t need it now. We’ve been 800 years, 300 years, 70 years, depending upon whose history you read, trying to resolve the difficulty that is Northern Ireland. And until we got George Mitchell [the American who chaired the peace talks], we never even came close. So it’s evident that we can’t do it alone. It’s evident that we do need help. But not help as in someone who knocks heads together. Help as in someone who creates a judicial process so we can all function within it. It’s about demanding, and determining that we know each other as people. That the people of Northern Ireland get a chance to begin to break down the barriers. That will only happen within the parameters of the Good Friday Agreement.

The Good Friday Agreement is the only vehicle upon which decommissioning can or will be delivered. Do I hear the grand moralists taking the wheels off the Good Friday Agreement? I’m afraid I do. I wonder is decommissioning really the issue? I hear other grand moralists saying that Northern Ireland has its first opportunity for accountable democracy. But if that accountable democracy isn’t as pure as [they] would like it to be [they] would have to bring down in order to protect it.

Having grown up in a society that had no accountable democracy, a society that is awash with illegal weaponry, these are alien concepts to me. Here we have the vehicle and the opportunity upon which that weaponry can be stored and packed and taken out of our society and I’m hearing people say No, I want it today. It must be today, it must be on my terms and better still doff your cap and bow deeply and appreciate me as the wonderful, great democrat who is determined to deliver the peace as he imagines it, rather than the true peace, which is people coming and living together.

Today, before I came here, I found that the process is likely to be parked. I don’t advocate, with the summers that we’re used to, that we set this process down and leave a vacuum which will be filled by those on both sides who have shown, whether it be Omagh, whether it be Rosemary Nelson, whether it be other attempts to kill people in Northern Ireland, that there is an adequate number and an adequate armament for people to try to put this process down because they can’t countenance change.

The only hope for our people is to go up the avenue of vision together. Anything else is not acceptable. Anything dealt with outside the Good Friday Agreement is not acceptable.

The following are excerpts from David Ervine’s answers in the session that followed his remarks.

The Good Friday Agreement

The Good Friday Agreement is truly a work of art … you will see elements of it being exported to other parts of the world, where other divided societies will take it, not as a perfect blueprint, but will learn from what’s in it. We’ve achieved something wonderful.

The Irish Government

If they [the Irish government] are guilty of anything in recent times is that they massively increased the expectation of the unionist population that the provisional IRA would decomission prior to the creation of a Northern Ireland government agenda. It was wrong, it was alient to any concept analysis that they could have had. And I wonder at times why they went down the avenue that they did. But I have to say that at this point in time, I can make no sense of it or rational answer to that. I asked the Taoiseach himself,f and I did not receive a satisfactory answer to that.

Dealing With a Quagmire

Now we can go round the houses and apportion blame, but I hope that I don’t have to do what I’ve had to do before, along with other colleagues. I don’t want to have to go to someone’s door and say, Hello Mrs. Brown, I have bad news for you. Your son’s just been killed. Or arrested. Or many of those other things that have happened. That’s the practical difference that’s happening in Northern Ireland, and it’s something that’s worth holding on to. The guns are silent. The fact that they exist is an anathema, and should be an anathema to us all. But being upset about it doesn’t necessarily mean we’ve cured the problem. We’re dealing with a serious degree of history, with massive divisions, with brutal and awful sectarian attitudes. And the truth of the matter is that we’re dealing with a quagmire. Now the choice we have is to recognize that we’re dealing with a quagmire, and go home and wash our hands, or to continue dealing with a quagmire and provided we’re taking small, even laborious steps in the right direction, then surely that makes it all worth while. So while there is a suggestion of free fall, unless it hits the ground, I refuse to give up on it.

The Hillsborough Declaration

The Hillsborough Declaration was an attempt, or we were led to believe it was an attempt, to break the impasse of decommissioning. It was an illusion. It was a sham. It was shameful.

It was controlled and manipulated by two governments who really should know better. And I advocate that no crows nest of a similar nature has ever, ever, been constructed, not only in Northern Ireland, but anywhere where trust is at an absence, because when you behave disingenuously, you don’t build trust. You maximize the levels of distrust, and I’m afraid that’s what happened at Hillsborough.

There was [also] a suggestion that legal weaponry and illegal weaponry would be each used in a form of tokenism in relation to getting us over the hurdle of decommissioning. The political party to which I belong absolutely and completely rejects the theory that legal weaponry and illegal weaponry are joined.

That’s not simply being moralistic. The reason why we had a war in the first place is the lack of democracy and the lack of appreciation of how you manage a divided society. That is the core of our difficulty, not the fact that we killed each other because of that. And we mustn’t justify people’s wars. And to justify paramilitary wars is very simple, just put their weaponry alongside the legal and designated forces of law and order and you’ve done exactly that. It mustn’t happen.

The Hillsborough Declaration

We are faced with a situation now where it really is down to the will of the people of Northern Ireland. They are either are ready for peace or they’re not and I know in my heart they are ..[But] we are finding it very difficult for our leaders to move forward. They are all looking for comfort blankets but the only people that can give them comfort blankets are their enemies or perceived enemies, and it is very hard for the enemy to give the comfort blanket when the enemy is in trouble himself. That’s the difficulty we are in. And in some ways the only hope, I believe, is not just to restate or resell the Good Friday Agreement but to identify that there is no Plan B.

The Good Friday Agreement is all that there is, and within the Good Friday Agreement I believe in my heart there is not only the opportunity to clear the hurdle of decommissioning but there is the swift opportunity to show the people the merit and benefit of having done so in the first place.

Only when we collectively take the responsibility for the mess we are in as well as for the good times we are in, do we begin to build true relationships and foster levels of trust. The real role models are the politicians, who have got to accept that they have a model that will work. When they move to making sure that [the Good Friday Agreement] is sacrosanct and can not be demolished or diminished, that in itself will build the trust that will carry down to the rest of the community. The answer is “stick to it,” for there can be no Plan B.

Editor’s Note: This article was originally published in the June/July 1999 issue of Irish America. ⬥

Leave a Reply