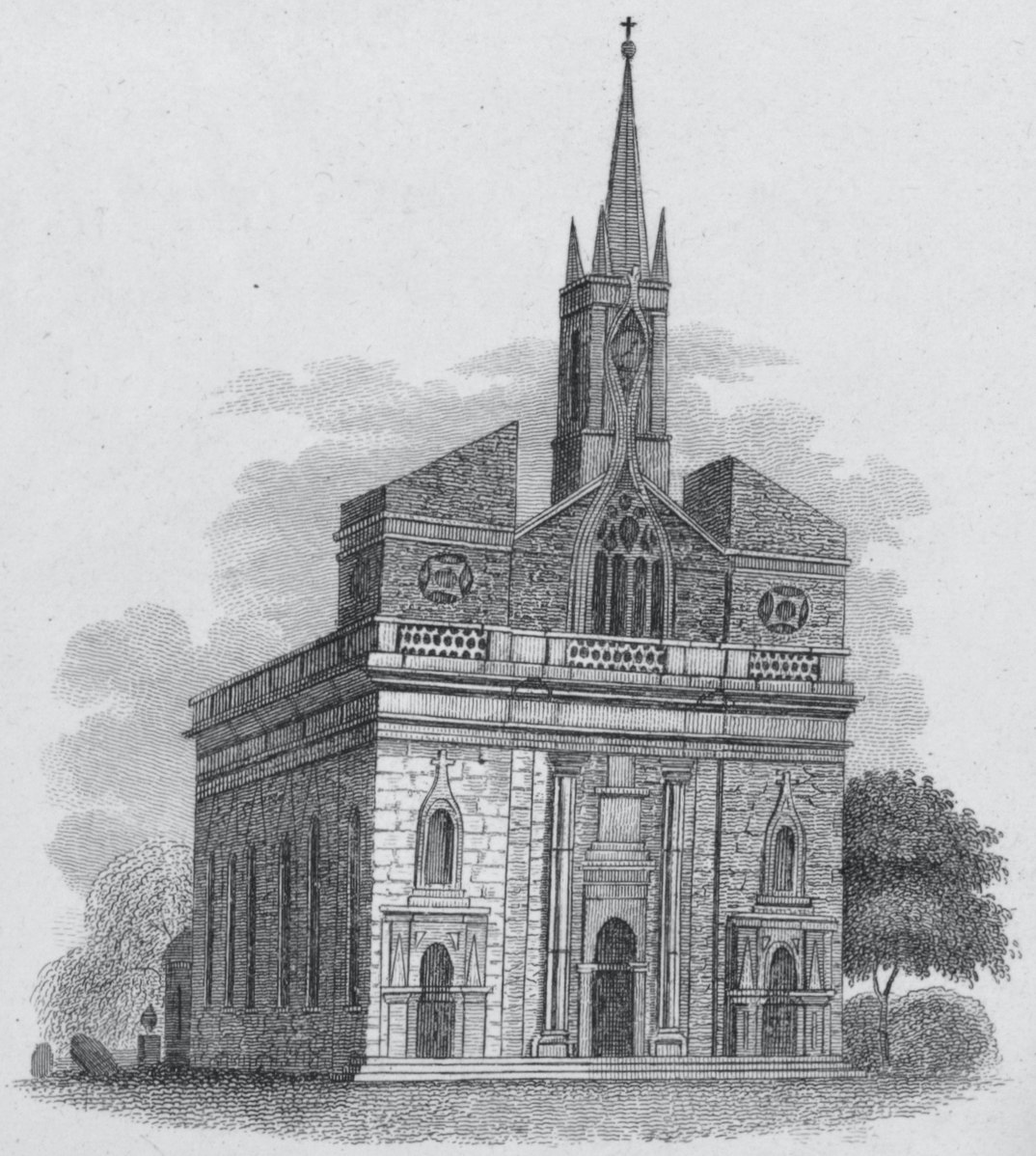

You could be forgiven for thinking they had never left. But it was not the world-famous, stately edifice that stands on Fifth Avenue between East 50th and 51 st Streets that was the center of attention. No, it was the far more humble Old St. Patrick’s Cathedral, located far downtown at the very unfashionable intersection of Mulberry and Prince Sts., right where what is left of Little Italy meets bustling Chinatown.

The occasion was the 136th anniversary of a solemn requiem Mass that was said for the dead of the Union Army’s famed Irish Brigade of the American Civil War. Consisting almost exclusively of Irish immigrants recruited from the North’s urban slums, and, not infrequently, the docks where the immigrant ships landed, the brigade had suffered grievous casualties in the Peninsular Campaign, and the battles of Antietam and Fredericksburg. Yet to come were Gettysburg, and the fearful slaughters that were the Wilderness, Spotsylvania, and Cold Harbor.

Dozens of Civil War reenactors, clad in period uniforms and carrying authentic Civil War-era weapons, marched through the streets outside the old building to the accompaniment of bagpipes, drums and fifes. They followed the exact route that the Irish Brigade’s “Fighting 69th” Regiment had taken when it marched off to Washington on April 23, 1861, in response to President Abraham Lincoln’s call for troops to suppress the Southern rebellion.

The reenactment, organized by the church’s development officer, T. Michael Pitts, was a fitting event for Old St. Patrick’ s, continuing its long tradition as New York’s oldest standing Catholic church and the fast Catholic cathedral in America named for Ireland’s patron saint.

The name was natural, given that at the time its cornerstone was laid on June 8, 1809, the building stood in the midst of a crammed slum that was rapidly filling with Irish immigrants, attracted by America’s anti-British stance and declared policy of religious tolerance. (Often honored more in the breach at that time.)

At the beginning of the 19th century, all of the United States and its territories were a part of the Diocese of Baltimore. But the rapid growth of the Catholic population meant this arrangement was no longer tenable. In 1808, Pope Pius VII established four new Sees: New York, Boston, Philadelphia, and Bardstown, Kentucky. Fr. Richard Luke Concanen, a native of Co. Roscommon, was named to fill the New York post. And it was in expectation of his imminent arrival that work was begun on the new cathedral that would serve as the bishop’s seat.

But the military and political chaos of the Napoleonic Wars kept Concanen stranded in Italy. He died in 1810, having never once laid eyes on his flock.

At almost the same time, St. Patrick’s rector and the Vicar General of the new diocese, the Rev. Anthony Kohlman, was making American legal history. He had acted to rerum goods stolen from a merchant when the thief had confessed the crime to him during confession. Protestants saw an opportunity to discredit the Church and dragged the priest before a grand jury, where he refused to divulge the identity of the penitent.

Placed on trial, Kohlman was ably defended by Thomas Addis Emmet, a Protestant Ulsterman and exiled older brother of the hanged patriot Robert Emmet, and another veteran of the 1798 uprising, William Sampson, who founded the Friendly Sons of St. Patrick to assist Irish immigrants. They won Fr. Kohlman’s acquittal, and in the process established the sanctity of the confessional in American law.

The same disorder that had prevented Bishop Concanen from taking up his duties had delayed work on St. Patrick’s, and it was not until Napoleon was decisively defeated in 1815 that work was sufficiently advanced that St. Patrick’s could be dedicated.

On May 4 of that year, the Mayor of New York, accompanied by many aldermen and leading citizens, turned out to witness the solemn dedication of St. Patrick’s by the visiting bishop of Boston. In November, Bishop John Connolly, another Roscommon native who had been consecrated bishop of New York in Rome, arrived to become the first resident bishop of New York.

Two years later, a “Charity School” was opened in the basement of the church. And across the street, at the corner of Mott and Prince Sts., the oldest Orphan Asylum in New York was opened under the auspices of the Roman Catholic Benevolent Society. It was at that orphanage that Mother Elizabeth Seton, the first American-born saint, established her order in New York, the Sisters of Charity.

The old churchyard and the burial vaults that run labyrinth-like beneath the structure contain the final resting places of many famous New York Catholics. Andrew Hardgan and Peter Hargous and other founders of the Emigrant Savings Bank have family plots in the crypt. So does Dominic Lynch, a ratifier of the U.S. Constitution and first president of the Friendly Sons of St. Patrick. Countess Annie Leafy, the first American Papal countess, lies in a vault beneath the cathedral.

Originally buried in the churchyard was the Venerable Pierre Toussaint, a black man born a slave in Haiti and whose cause for sainthood is under consideration in Rome. So was Archbishop John “Dagger John” Hughes, the first archbishop of New York and the builder of the more famous new St. Patrick’s Cathedral uptown.

Hughes was a fiery man who defended his flock with more than words. More than once, he assembled his parishioners to physically defend the cathedral from assault by anti-immigrant nativist mobs. One threat, on election night in November 1844, was so serious that the archbishop armed 3,000 members of the Ancient Order of Hibernians with muskets and stationed them on the walls surrounding the churchyard. Simultaneously, he wrote a letter to Mayor James Harper threatening to turn the city into “a second Moscow” if any harm came to St. Patrick’s. The nativist mob, numbering around 1,000, thought better of their plans to burn St. Patrick’s and dispersed.

The Civil War, naturally enough, was a turbulent time. Hughes supported the Union war effort and thousands of Irishmen flocked to the colors in their eagerness to prove their loyalty to their adopted country. Hughes became an unofficial adviser to President Lincoln, traveling to France, Spain and England in a successful effort to keep those countries from intervening in the war on the side of the Confederacy.

Closer to home, however, the high casualties suffered by the Irish Brigade and other Union units with substantial numbers of Irish soldiers saw an alarming increase in the number of black-clad widows in the streets of the mostly Irish neighborhoods around St. Patrick’s, and the orphanages filled rapidly. When conscription was introduced and fell heavily on the poor Irish, the smoldering discontent among the New York Irish broke out in the bloodiest riots in American history. Only the personal plea of Archbishop Hughes helped end the violence.

Happier occasions took place within St. Patrick’s as well. St. John Neuman was ordained a priest there, and Hughes was the first bishop to be consecrated in New York. No effort was spared to make the were erected outside the windows to afford additional accommodation to spectators.

But even then, Old St. Patrick’s days as the center of New York’s Catholic life were numbered. Hughes envisioned a cathedral far larger and more grand than the relatively humble church on Mulberry St. could provide. He wanted a cathedral “of suitable magnificence,” one on the most prominent street — Fifth Avenue — in the middle of the largest city in the country. Above all, an edifice that would announce to the world that Catholicism, particularly Ireland’s own distinctive brand of it, had “arrived” on the American scene. And there it would stay.

So in 1859, construction began on the huge new St. Patrick’s Cathedral further uptown. At that time, the line of settlement ended at around the present-day 42nd St., so many called it “Hughes’ Folly.” The archbishop was undeterred. He knew the city would grow up around his new cathedral, as indeed it did.

Meanwhile, Old St. Patrick’s suffered a blow in 1866 when it was partially destroyed by fire, but was repaired and rededicated by Hughes’ successor, Archbishop John McCloskey. The greatest event in the old church’s history came on April 27, 1875, when McCloskey received there the red hat of a cardinal, the first American to be so honored. In attendance that day, in addition to the mayor of New York, was a future President of the United States, Chester Alan Arthur.

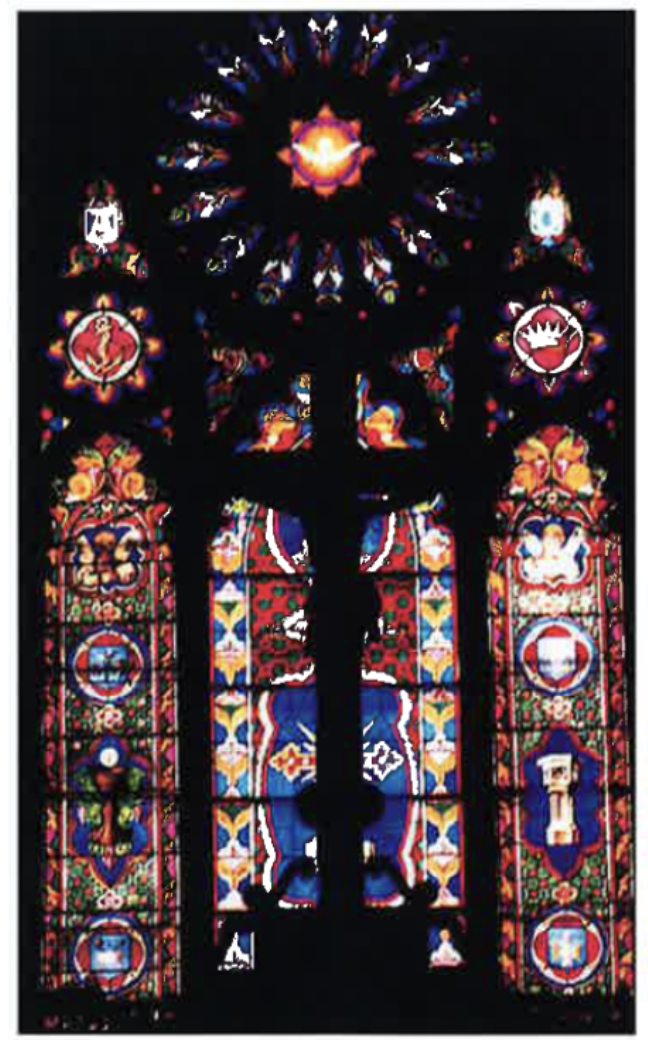

Four years after that great event, the uptown cathedral was finally finished and Old St. Patrick’s saw the end of its reign as seat of New York’ s Catholic prelates. The old edifice reverted to the status of an ordinary parish church. The Irish character of the neighborhood was gradually giving way to Italians. The latter contributed much of the elegant glass and stonework now visible in the church, as well as many vocations.

Approaching its bicentennial, Old St. Patrick’s continues to serve new generations of immigrants, mostly Dominicans and, increasingly, Chinese. But however much it changes, it forever stands as a sentinel of the history of the early Catholic Church in America, and the Irish immigrants who built it.

Leave a Reply