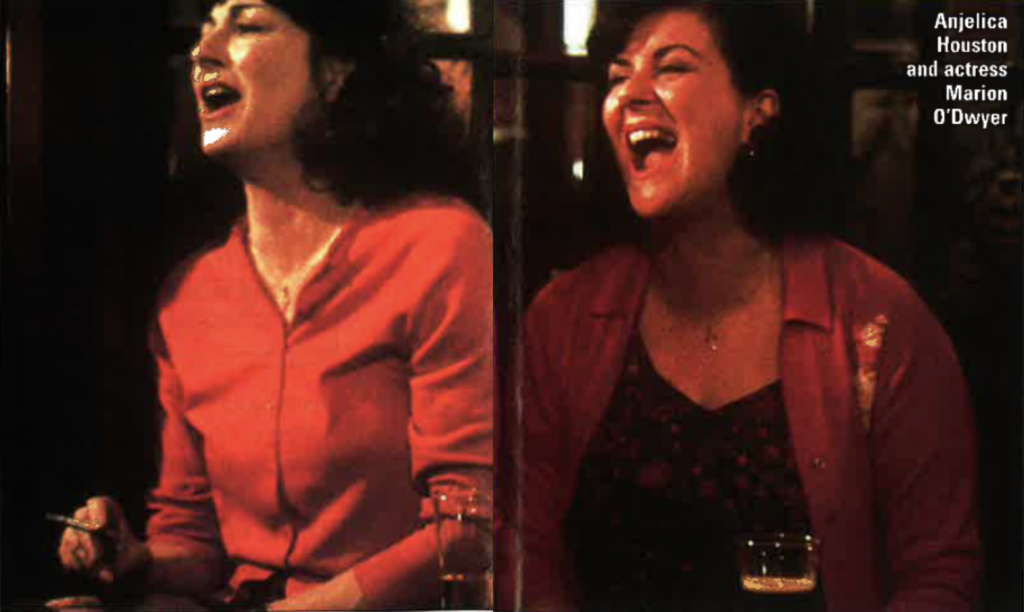

Kelly Candele visits the set of The Mammy In Dublin and talks to Anjelica Huston.

Anjelica Huston looks calm and comfortable as a makeup artist applies a touch of lipstick before a midnight promotional photo shoot in Dublin, Ireland. She is up late on a drizzly Friday night completing the last few “emotional” shots on her new movie The Mammy, based on a novel of the same name by Brendan O’Carroll, a film that she is both starring in and directing.

The movie skylights and faintly falling rain create a surreal quality on the set that seems to encircle her and her crew in a shimmering light, bathing them in an incandescent glow. Twenty or so people wait patiently for the photo shoot to end on a small street in the working-class Ringsend district of Dublin that has been turned into an outdoor marketplace.

It’s the tenth and last week of the shoot but Huston is upbeat, hanging out with the crew in front of P.J. Foley’s Select Lounge and Bar, the “center of the universe” in the book for the local population. Down Moore Street, the central location of the movie, is Cecil’s Barbershop and Bookmakers right next door to McCabes News Agents. In a nice touch of detail and realism, the headline of The Irish Times on the stand in front of McCabes reads, “De Gaulle Arrives For Rome Talks.” The date on the paper reads May 30, 1967. Vegetable stalls line the street filled with tomatoes and bell peppers so deeply red they seem to jump out of their crates.

For Huston, the vibrancy of color on the street reflects the intensity and richness of the film’s characters. “It’s an odd thing that happens in Ireland when the sun comes out against the slate blue skies,” she says. “It makes colors pop. That’s the way I see this movie. It’s emotionally and visually saturated. The characters — they’re fruits and vegetables.”

Agnes Browne, a Moore Street dealer, is one of those characters and the role that Huston plays. A recently widowed mother of seven, Agnes struggles to survive dim-witted social workers, mean-spirited nuns and the loss of her closest female friend. Her fantasy is to dance with fabled singer Tom Jones. The story focuses on the daily intimacies and escapades of Agnes’ young children and the bond of female friendship that sustains lives in what outsiders might regard condescendingly as “a hopeless situation.”

“It’s quite a passionate story,” Huston explains, “where the love affair, by which I mean a deep friendship, happens between two women. It’s how you survive the loss of a great friend and ultimately, how you hold onto your dreams. To me it’s a fairy story — a Christmas story. It’s romantic but also about people living within the confines of rather impoverished circumstances.”

It was not an easy decision for Huston to develop this project. With so much to choose from in Irish literature, and she’s read much of it, The Mammy was a somewhat unlikely choice. But the richly textured characters appealed to her as an actor.

Reflecting on the book she observed that it was not a terribly obvious comedy. “What I liked was that the story had a lot of ups and downs and waves. You go from wild hilarity to something kind of shocking and that was attractive to me as an actress. It’s a sort of Latin quality the Irish have,” she added. “You find poignancy in humor and laughter in tears.”

She found the book through director Jim Sheridan who approached her with it at a screening of her film directoral debut, Bastard Out of Carolina. The next step was arranging a meeting with the writer O’Carroll.

The Mammy is a story about strong women written by a man with appreciation for the survival instincts and strength of purpose of Dublin working-class women. Comedian and novelist Brendan O’Carroll’s mother, Maureen, was the first woman in Ireland elected to Parliament, winning a seat for the Labour Party in 1953. O’Carroll was the last of ten children, “one more time for old times’ sake,” as he describes his parents’ attitude. In the beginning of his book he says he was “lucky to be born in the Finglas area of Dublin, a place where strong women are in abundance.”

While his mother, a committed socialist, was out saving the world, young Brendan was hanging out with the characters that populated the Moore Street Market, where you could find, according to O’Carroll, everything from flowers to an anchor. It’s women that drive both his book and the script.

The women of the market provided O’Carroll with the jaunty linguistic rhythms of working-class Dublin and great material for his wicked sense of humor. In the novel he describes how Winnie the Mackerel, one of the market fish sellers, responds to a customer’s inquiry as to the freshness of the fish. “Fresh! Missus, if you bring that home to your fella, ye’ll be putting him out with the cat tonight.”

“In the market females were the dealers and males did the picking up and cleaning up,” O’Carroll explained. “I have a better feel for female characters than male as my father died when I was seven. I grew up in a female-oriented family and hung around a femaleoriented world.” O’Carroll, who was a waiter for eighteen years before trying stand-up comedy, also plays a wino in the film who wears dungaree trousers with pajamas underneath and the wig that Tom Cruise wore in Mission Impossible.

O’Carroll describes the first meeting with Huston as “the most enthralling week of my life.” The way O’Carroll describes it, Huston loved the “Dickensian” quality of the book but saw several problems translating it to the screen. “I arrived in Los Angeles during Saint Patrick’s week of 1996,” O’Carroll remembered. “We worked shoulder to shoulder ten hours a day trading blow for blow with no set ideas.” O’Carroll went back to Dublin and wrote the screenplay in five days. He also realized that during his work with Huston he was getting much more than an interested actor’s collaboration — he was getting director’s notes. After considering Emma Thompson and realizing she was just not right for Dublin, O’Carroll and Sheridan, a producer on the movie, asked Huston to direct.

Directing a film in Ireland is also a nostalgic homecoming for Huston. She lived in Ireland as a child, almost steadily from age two through eleven.

Her father, director John Huston, had a house in Galway for close to twenty years which he described in his autobiography An Open Book as being “part of my soul.” Looking back on her youth in Ireland Huston sadly reflected on how dramatically things had changed. “It was still Molly Malone’s Dublin to a great extent back then. It had this French influence and Georgian influence and there was a kind of rarity that you don’t see much anymore, particularly with the advent of Planet Hollywood and the Americanization and universal coverage we are all going through. Television came to Ireland in 1967 or thereabouts, and I remember watching Cassius Clay and the Bay of Pigs. All of those things Ned Jordan covered in The Butcher Boy. They were momentous and indelible times.”

The Mammy, then, is a throwback to a more innocent but not uncomplicated time. How could a single woman with seven children live an uncomplicated life? And Ireland in the late 1960s was a country in transition. While on this night, Huston is dressed in a working-class woman’s shinlength wool skirt and black tie-up shoes, costume designer Joan Bergin pointed out that changing fashions indicated an emerging change in consciousness. Bergin, who went to Glasgow searching through their famous old-clothing shops, approached the movie as if it were “a magic time where there were odd combinations of clothing even for the women who worked in the market. There is one woman who works in the street who is very trendy.”

Not surprisingly, the consensus on the set was that Huston the director was decisive, strong and knew what she wanted. But according to veteran Irish actor Gerard McSorley, she also allowed him to bring his own experience to his small role as an undertaker in the film. “She’s very trusting of actors and gives you the freedom to do what’s appropriate with the character.” O’Carroll added that “she has a very gentle and persuasive way of directing — like a ghost; you don’t realize it and the shot is done.”

While the film is set over thirty years ago, both the tragic reality and hope of contemporary Ireland were not far from people’s minds. A few weeks before the end of shooting the Omagh bombing took place, killing 29 people. Money was collected on the set that McSorley, who grew up in Omagh, took to the relatives of the survivors. And on the last rainy night of shooting, President Clinton was in Dublin doing his best to consolidate the peace process and stay one step ahead of questions about Monica.

“Clinton’s very charming,” Huston said. “But sometimes charm can be a dangerous thing.”

When Anjelica’s father John Huston described fox hunting, his favorite pastime during his years in Galway, he stated that when a barrier seemed too high to jump the rider had to “throw your heart over the wall and follow it.” If you were a bit lucky you would survive the leap. Anjelica Huston has thrown her heart into The Mammy for a number of reasons. She loves Ireland, she’s challenged by the material as an actor and director, and she identifies with Agnes Browne. “I’m drawn to survival stories. I also seem to be attracted to stories with a lot of children because I don’t have any of my own so it’s my way of supplying myself with them.”

She is not sure when the film will be released — it depends how editing goes. McSorley can’t wait, and notes, “When people see Tom Jones singing at the Gaiety Theater in Dublin…that alone [will be] worth paying to see.”

Editor’s Note: This article was originally published in the April / May 1999 issue of Irish America. ⬥

Leave a Reply