From Bull Run to Appomattox, the 6th Louisiana’s Irish Confederates fought proudly

On April 28, 1861, two weeks after Confederate guns had fired the first shots of the Civil War against Fort Sumter in Charleston harbor, a notice appeared in the columns of The Daily Picayune, one of New Orleans’ leading papers. It was a call to arms aimed at the thousands of Irish immigrants of the city. Under the heading “Company B, Irish Brigade,” the notice read:

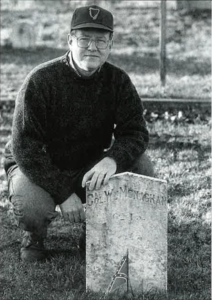

“The roll for the formation of Company B, Irish Brigade, will be opened on Monday, the 29th inst., at 10 o’clock A.M., at the Olive Branch Coffee House, corner Erato and Tchoupitoulas streets, the undersigned will be present every day and evening until the roll shall be filled up, when the members will elect their officers. Prompt action is now expected of every Irishman in the present crisis. (Signed) Wm. Monaghan.”

Whether the selection of the Olive Branch Coffee House as a site to recruit for war was an expression of William Monaghan’s Irish sense of ironic humor is uncertain, but there is no doubt that he was a true son of the auld sod. Born in Ireland, he worked in New Orleans before the war as a notary public, a position requiring education and a literacy level that many of his fellow immigrants lacked. He was a man marked for leadership, and would in time rise to command the Confederate regiment that is sometimes called the South’s “Irish Brigade” — the 6th Louisiana Volunteers, a unique infantry regiment in General Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia.

What set the 6th Louisiana apart from most other Confederate fighting units was the nature and background of the men themselves. It was a regiment dominated by Irish Catholic immigrants. Roughly half of its rank and file listed Ireland as their birthplace, and many more were American-born sons of Irish immigrants. Monaghan’s company became one of ten that composed the 6th Louisiana, originally numbering 916 volunteers. The men of the regiment were largely foreign born, including one company of German immigrants from New Orleans. Only a small minority were native Louisianans. The names on the regiment’s rolls read like a guest book at an Irish wake, dominated by Bradys, Donovans, Fitzgeralds, Kellys, Murphys, O’Rileys, and similar surnames of the old country. These were the Irish Rebels of the Southern army: driven by famine and poverty from their homeland only to find themselves caught up in the epic struggle of their adopted country.

Just as the Irish immigrants in New York, Boston, Philadelphia and other Northern places rallied to the Union cause, these Irish who poured into New Orleans in the 15 years before the Civil War embraced the cause of the Confederacy with typical Irish loyalty and passion. Though less numerous — and destined to be far less famous — than their countrymen who fought for the Union in the fabled Irish Brigade, these Irish rebels wrote an equally stirring story fighting for the Confederacy. They are the Civil War’s forgotten Irish sons — the Confederate Irish.

The Confederate Irish were far outnumbered by their countrymen in the Northern states when the war broke out in 1861. Most of the more than one million immigrants from Ireland who flooded America’s shores in the 1840s and 1850s, as a result of Ireland’s disastrous potato famine, landed in the North. But many landed at Southern ports or worked their way south, so that in 1860, the Irish were the largest white immigrant group in the Confederacy, numbering nearly 85,000. And when the war came, Irishmen on both sides of the North-South divide answered the call to arms. While some 150,000 Irish immigrants in the more populous Northern states eventually served in the Union army, an estimated 30,000 Irish-born Southerners fought for the Confederate army, and Irish units were raised in eight of the eleven states of the Confederacy.

Scores of heavily-Irish units that often bore colorful names gave the Confederate army its own Celtic flavor. Savannah produced the Irish Jasper Greens, two companies of the 1st Georgia Volunteers. The Emerald Guards, a company of the 8th Alabama infantry regiment, were Irishmen from Mobile. South Carolina produced the Emerald Light Infantry and the Old Irish Volunteers of the 1st South Carolina infantry, from Charleston. The 10th Tennessee regiment from Nashville was largely Irish, while the 1st Virginia infantry included Irish immigrants from Richmond.

No other state produced as many Irish Confederates as Louisiana, and no city as many as New Orleans, which in 1860 was home to nearly 25,000 immigrants from Ireland, more than any other place in the South. Several thousand Irishmen fought in Louisiana Confederate regiments, scattered throughout the ranks in some regiments and concentrated together in a few, most notably the 6th Louisiana. The Irishmen of the 6th Louisiana were mostly common laborers: dock-workers, riverboat hands, bricklayers, blacksmiths, wagon drivers, seamen. Some were store clerks, printers, barkeepers or bakers. They were the urban underclass of their day — immigrants of little or no formal education, packed into New Orleans’ poorest neighborhoods, competing for jobs with the city’s free blacks and slaves, scrambling to grab the bottom rung on the social and economic ladder in a city whose establishment regarded them as the lowest order of humanity.

After the war, the story of these Irish Confederates fell into the obscurity of unrecorded history for 130 years. Unlike the famous Irish units of the Union army, such as the 69th New York and the 28th Massachusetts regiments of the storied Irish Brigade, the 6th Louisiana and other Southern Irish units have been ignored by historians. But theirs is a fabulous story, long overdue in the telling, that stretches from the first Battle of Bull Run in July 1861 to the last gasp of the Confederacy at Appomattox Court House in April 1865. The Irishmen of the 6th Louisiana were there every step of the way, in all the famous battles of the Eastern theater of the war, down to the tiny band of 55 nearly starving, rag-tag soldiers who surrendered with Lee at Appomattox.

This is the story I have devoted the past three years to uncover and tell in my new book Irish Rebels, Confederate Tigers, published in July 1998 by Savas Publishing Co. I was inspired by my own Irish Confederate ancestor, Dennis Cavanaugh of Galway, who joined the Confederate army at age 18 in 1862, fought to the end of the war, and died in New Orleans’ Old Soldiers home in 1917. For Dennis and all of the Irish Rebels who fought for the South, but never have received the attention they deserve, this work has been a labor of love.

There is no way to quickly summarize the incredible story of the 6th Louisiana, which covers four years and practically every engagement, large and small, between Union and Confederate armies of the East — Manassas, Antietam, Gettysburg, the Wilderness, Cold Harbor, Petersburg and more. These Irish footsoldiers fought and bled and died on all the famous battlefields of the East. They impressed their commanding generals with their Irish enthusiasm and grit — fierce in battle, rowdy in camp, playful on the march, enduring to the end. The 6th Louisiana, wrote Confederate Major General Richard Taylor, who commanded them during Stonewall Jackson’s famous Shenandoah Valley Campaign of 1862, “was composed of Irishmen, stout, hardy fellows, turbulent in camp and requiring a strong hand, but responding to kindness and justice, and ready to follow their officers to the death.”

Follow them to the death they did. Of the 1,146 men who eventually served in the 6th Louisiana, at least 224 were killed and 104 died of disease. Hundreds more were wounded and maimed, or captured and sent to Northern prison camps. There is a less-glorious side to the story too: 200 or more of the 6th Louisiana men deserted, some during the early months of the war and many more later on when the Confederate army was ragged, hungry and hopeless. A few joined the Union army as a way to get out of wretched Northern prison camps. One of these turncoats, a young New Orleans Irishman named John Connolly, was recaptured by the Louisiana Confederates and executed by firing squad in a tragic and moving spectacle described by one officer as the “most unpleasant and revolting duty” he had ever discharged.

The 6th Louisiana’s bloody war record is illustrated by the fact that three of its commanding colonels were killed in battle — a record few Southern regiments can match. Its first commander, Colonel Isaac Seymour, a 56-year-old former New Orleans newspaper editor who was killed at the Battle of Gaines’ Mill near Richmond in June 1862, was not Irish. His two successors, however, were both immigrants from Ireland and shared Seymour’s fate: Colonel Henry Strong, killed at Antietam in September 1862, and Colonel Monaghan, killed in August 1864 at Shepherds-town, now in West Virginia.

They are among the heroes in a story full of heroes and scoundrels, glory and shame, triumph and tragedy, victory and defeat. Tracing their story, I have found myself awed by their devotion to duty, their sacrifice and their endurance — and this from a band of immigrants who had no deep roots in the South, no stake in slavery, and nothing to gain from the war except the long-denied respect of their fellow Southerners. They fought, I believe, to prove their honor, to show their character, and to finally establish themselves as true citizens of the new country they had adopted as their home. North and South, the immigrant Irish finally claimed their rightful place as Americans during America’s great national tragedy, and left a record of which all Irish-Americans can be proud.

Editor’s Note: This article was originally published in the February / March 1999 issue of Irish America.

Leave a Reply