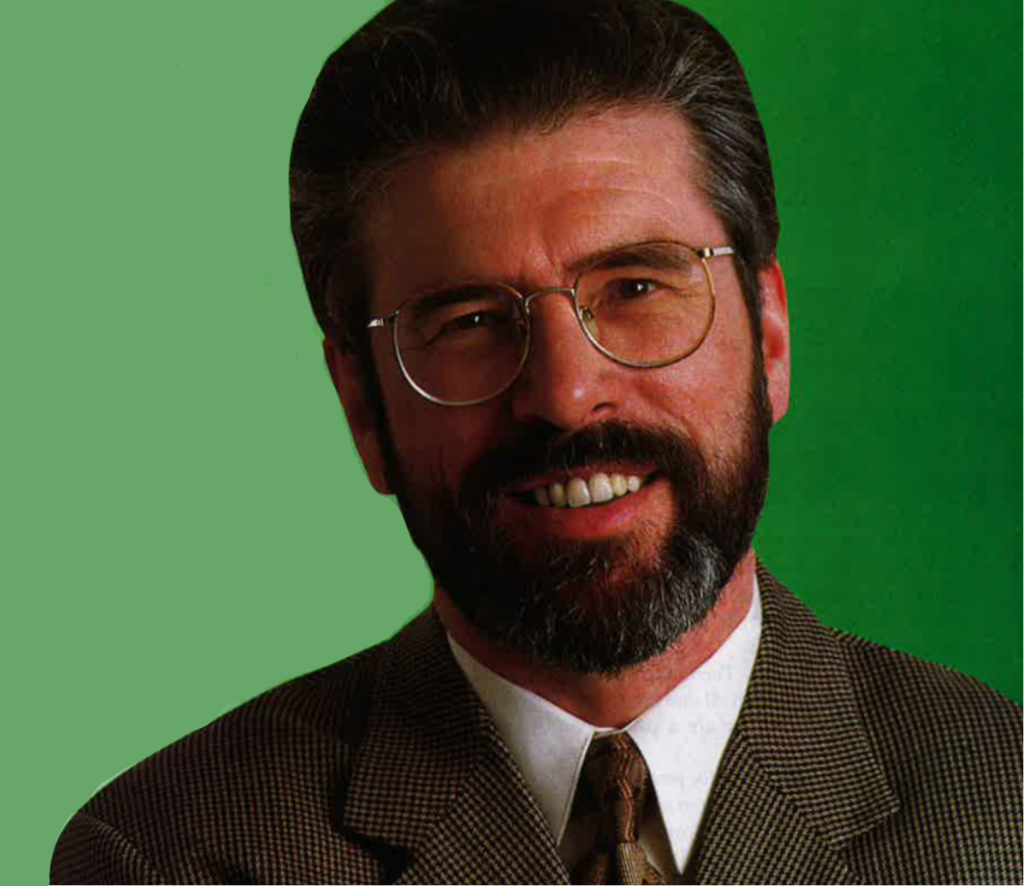

History will be the ultimate jury, but Sinn Féin leader, Gerry Adams, one of the architects of the lrish peace process, is likely to emerge as one of the key Irish politicians of the 20th century.

Unionists see him as a machiavellian schemer, with no commitment to peace and reconciliation with their tradition. The SDLP — and one suspects the British government — are also suspicious and would prefer to keep him at arm’s length.

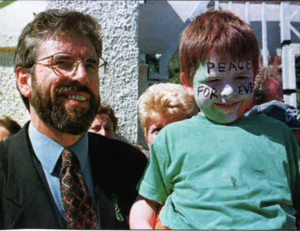

His appearance, however, at any republican rally, or in the streets of his native Belfast, is enough to send his admirers into paroxyms of delight.

Few could argue with an analysis that Adams is among the most effective Irishmen of his generation.

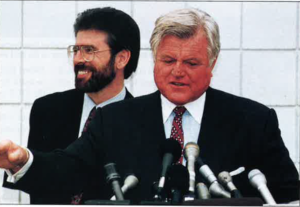

He has attained the status of celebrity and is probably the only Irish politician anyone outside Europe or the U.S. could name. It’s been a long road for the bearded, bespectacled, thoughtful and determined West Belfastman, who will be 50 in October of this year, and the story is far from over yet.

One of the most intriguing and visionary Irish politicians in the country’s troubled history, Adams left school at the age of 16 and became involved in political agitation in his native West Belfast.

Although he will never comment or confirm press reports, it’s believed he was a senior IRA figure during the turbulent 1970’s. He was interned without trial in 1971 and housed in the IRA compound in the Maze jail.

Adams took part in a failed escape attempt, for which he was jailed for 18 months. He was temporarily freed in July 1972 and flown to London at the age of only 24 for direct talks with the British government.

While in jail he wrote a series of letters to An Phoblacht/Republican News, under the pseudonym “Brownie” discussing political strategy and ways forward for republicanism.

As early as 1979, he told a Wolfe Tone commemoration that republican aims could not be achieved by military means alone. In 1980 he told a party conference that the British realized there could be no military victory and it was time republicans realized that too.

Adams rose to national prominence at the time of the 1981 hunger strike and became the main figure in a resurgent Northern group of “young turks” who vied for leadership with the “old guard” led by Ruairi O’Bradaigh and Daithi O’Conaill.

He was elected to the House of Commons (and refused to take his seat) in 1983, unseating Gerry Fitt and became leader of Sinn Féin the same year.

In 1984 he was attacked by loyalists in Belfast city center. He was shot five times, but escaped with his life.

In 1986 he led a successful campaign to overturn the party’s policy on abstaining from taking seats in the Dail and two years later began a series of meetings over six months with the SDLP.

While never repudiating the IRA campaign, he was publicly critical of some aspects of it, saying the IRA must be vigilant and responsible about its use of violence. In 1992 he lost his Westminster seat in a battle with the SDLP, when loyalists voted tactically against him.

By April 1993 he was meeting John Hume again in a process which led directly to the August 1994 IRA cease-fire. He remains one of the key figures in the Irish peace process, leading his party into the Northern Ireland assembly that meets again this month.

Married to Colette, and with one son, Gearoid, along the way, Adams has also become a successful writer of autobiography (Falls Memories, Before the Dawn), political theory (The Politics of Irish Freedom), fiction, including a book of short stories, The Street, and jail memoirs Cage 11.

He invariably refuses to give interviews about himself and is described by journalists as a polite, elusive, taciturn, even cold personality whose life almost entirely revolves around politics.

Friends and party colleagues in his “inner circle know a different person, who emerges in his own best-selling books as deeply humane. He is also religious, passionate and emotional, with an anger that flares rarely, but brightly, when roused.

He gave a very rare personal inteview to Irish America in the stark surroundings of Conway Mill, a disused linen factory where generations of West Belfast people laboured for slave wages in past years.

Outside in the corridors, phones rang and party officials bustled about their business, but for the two hours or so that we spoke, we were isolated in deep discussion — two people who’ve known each other and sparred together for over 15 years, but who had never spoken intimately before.

He spoke of his deep commitment to Irish freedom, coupled with a sense of humor and a sense of the tragedy that has moulded his, and his country’s experience.

The following is a transcribed interview between Anne Cadwallader and Gerry Adams

IA: Looking deep into yourself, what really motivates you? It must be a hard road. What keeps you working and taking risks?

GA: I am not on my own. The media see me as a key player, and with all due modesty I accept that I am, but we are a collective leadership.

My first motivation is that the people of this island can have peace, freedom and justice. Freedom from the British, from partition and military occupation. Also freedom from poverty and inequality.

A lot of people want that. What makes you different?

I am sustained by many things, including comrades and friends who make huge contributions. There are times when you are at a low ebb, that happens to anyone, it can be through sheer exhaustion.

At the moment, I’m exhausted. I’m in good form, but I know I have to take time out. The problem with taking time out is that you get depressed afterwards, coming back to it all.

Are you aware of the dangers of becoming a personality cult?

I’m very aware of the danger, but I don’t think we’re going to make that mistake. If you end up in high office and become divorced from people, your life could be reduced to televisual moments and sound-bites.

But if you work amongst people, then that is a great equalizer. People in a liberated area like this are always prepared to tell you what they think of you. They might say it politely or nicely, but you are accessible, you’re inviting people to make judgments.

When you take time out, can you switch off?

Yes. I still get the papers, if I am in Ireland, but I found in recent years I do have the ability to relax. I know the value of really switching off.

It’s difficult to get a really clean break, but if I do I can recharge myself.

Are there places you can go where you can be completely private?

Increasingly few. I can be on my own in singular occupations, like going off walking with the dog on a beach or into the hills. In the evening, I can’t socialize in public places. I go out with a few friends for dinner.

You’ve often said you would rather not have been a politician. What would you have done instead?

I really haven’t had much time to think about it. If you take this year, for example. It began with a killing spree by loyalists, then the Stormont talks, the Good Friday agreement, the referendum, the Assembly elections, then Drumcree. It’s been traumatic for everyone.

If you take last year, and the year before that, and before that. If I think back, this year was probably as difficult as during internment in 1972. Friends being killed, the horror of the hunger-strikes…

If I stopped being involved now, and I did something else, what I would do is write. Whether I would have had the confidence to do that earlier, or the experiences to write about, I don’t know.

Do you ever have panic attacks that this could all collapse and fail?

Yes. There are times when I am very conscious of the flaws in human nature. There are lots of questions I don’t have the answers to.

Do you find it difficult being in the public eye? You always have to be perfectly dressed, on duty, from the moment you step out of doors in the morning.

I used to think that it didn’t matter how I looked. But then I realized some time ago that when I was seeing people, at a constituency level, they expected me to be at least tidily turned-out.

And then I thought that, if you are invited to a wedding, you make the effort. This might sound silly, but you do it for other people. You’re representing them. If I wasn’t in the public eye you wouldn’t get me dressed-up at all!

What do you think of journalists, present company excepted, of course?

There are very good people, who work hard and who are professional. Journalists have to understand that if you go and talk to someone, and take their words and misrepresent them, out of context, for whatever reason, it can be very annoying.

I think I have a good relationship with journalists, but there are some, and some newspapers, which I won’t deal with because they consciously have a straight-forward political agenda.

Have you read any books recently, outside of politics, that have impressed you?

Every so often I take a pledge and start reading again. I’ve just finished Malachy McCourt’s A Monk Swimming, which is a lovely word play on the Hail Mary; “Blessed art thou amongst women…”

I have also recently finished Bill Bulger’s While the Music Lasts. He served for seventeen years as president of the Massachusetts Senate and he gave me his memoirs, which are highly entertaining.

I have a notion in my head that I should write a book of short stories, so I am digging out some great short story writers and studying them.

What technique do you use when you write?

I use a word processor now, and I recently got a laptop. I’ve just finished writing a small piece of a few thousand words about Bloody Sunday. I enjoy writing, I can lose myself in it.

It’s the first piece I have written in ages, since Before the Dawn, other than letters and speeches. I had to re-write it substantially, but I was pleased with the result.

It’s a matter of discipline. In all the books I’ve written, what has resulted is because of the deadline. Then when it’s printed, you look at it and see all the ways it could have been done better.

When was the last time you were really, really angry? Was it at the time of your outburst in Dublin Castle this spring when you said you were “pissed off” that Sinn Féin was being temporarily thrown out of the political talks?

(Long pause). Well, I don’t want to elaborate on this. I was very angry when that lad Andrew Kearney was killed.

(Kearney was shot in a so-called “punishment attack” in July, by a gang alleged by the RUC to include members of the IRA. He bled to death from a severed artery in his leg).

Then, Garvaghy Road last year. I felt guilty. I was down in Kerry with Martin Ferris for a post-election function for party workers. We left the function about one in the morning and as we were driving home, at about six o’clock, we heard the news that the people had been beaten off the road by the RUC.

I watched the first television pictures coming in, and saw the peelers [police] hacking their way into the people and I felt really, really…emotional.

You strike me as someone who does get angry, and who fights to control your anger.

Well, I do get angry. I can be foul-tempered at times. Apart from being crabby or in bad form, which we all can be at times.

In terms of my own personal life, I can be pushed pretty hard before I get angry, and then I flip out at what’s annoying me.

One of the things I realize about emotions is that hatred is a waste. You hear so much about the “hatred” here in Ireland. A friend of mine once said he hated someone, and that had sustained him for years. When he finally met the person, he realized he had no reason for hating him.

You can hate concepts, but I think when it gets to the point when you hate people, it can cloud your judgement.

I remember when Richard McAuley [a close aide and friend] and I were in Greece, in a car going from the airport in Athens, where we’d never been before. He was writing and I was dictating, and I looked up and realized where we were.

We saw the Parthenon, and we stopped what we were doing for a moment. It was crazy to be there and not notice it.

Even when we’re driving to Dublin, there are parts of the road I won’t work on. Like the ring-road around Newry, where you can see the South Armagh mountains.

What makes you sad? When was the last time you cried?

I am an emotional person. I make no bones about that. There are times when I feel very much like crying. This might sound a bit weird, but did you see the footage of the children in Sudan, the famine? That was the last time I cried, and that was only two weeks ago.

The one thing I’ve learned in my limited travels is that people are the same under the skin — color, race, gender are all distractions.

There was a fourteen-piece Mexican band on the Falls Road yesterday. No one under stood a word they were singing, but we knew they were patriotic songs about Mexico because there were shouts of “Viva Mexico” and so on.

The music and vitality of the people was wonderful and we all shared in that. Divisions and fears between people are exploited.

I was depressed watching the Paisley-ites in the Assembly recently — so much creativity going to waste, so much potential…

When Brid Rodgers was talking about Robert Hamill (a Portadown Catholic beaten to death by a loyalist mob in 1997), one of the DUP people shouted up, “He started the fight.”

That’s the sort of thing you would get kids shouting. That sort of thing is depressing.

When the three Quinn children were killed in Ballymoney, apart from the universal feeling, I got angry anticipating the reams of condemnatory statements about “evil men.”

I just knew that the guy who killed those children was an ordinary person, in drink or a frenzy of sectarian hatred — wound up by people who talk about Roman Catholicism, and the “purple whore of Rome” and the “anti-Christ” and all that. Crazy stuff.

What annoys me is public representatives talking in such disparaging terms, kindling fear about Roman Catholics. Then at the other end of the scale, someone goes out and does something like that.

The person making the inflammatory statements is not responsible for the actions of the person who throws the petrol bomb, but you cannot divorce one reality from the other.

Was it exciting to be young when the civil rights movement started? Do you look back to it as the “good old days”?

Someone said in passing recently that for someone out there today is the start of the struggle. So I’m sure someone will come into this office today and this will be their exciting time.

I am fifty this year, on October 6th. In 1969 I was 21. The Falls Road was in flames. It was exciting, it would be wrong of me to say that wasn’t the case. The escape I was involved in jail, it was all funny, humorous in a recklessly wired-up way.

But what tempers all that is that around me were people getting killed.

You were shot and seriously injured in an assassination attempt in March 1984 in Belfast city center. What are your memories of that?

It was sore! I had been caught up in an altercation on the night before polling day when the RUC tried to take a tri-color off a car. There was a tug of war and I intervened and got arrested.

From the day I was summoned to court, my antennae were up to that height (gestures to the ceiling). In the courtroom, I saw guys I was immensely suspicious of. I brought this to the attention of my late solicitor, Paddy McGrory, and he asked the officials if I could stay in court until the lunch break.

Every sixth sense that I had was shouting “Watch out.” I didn’t have the security then that I have now. A poor unfortunate man, Kevin Rooney, came down to pick me up. Joe Keenan, who’s since died of natural causes in the States, was in court for the crack. Sean Keenan from Derry was a witness in court.

We decided we would go to a well-known Belfast fish-and-chip shop called Long’s for lunch. We were shot very close to where the new Jury’s Hotel is now. It later transpired that because we had delayed — with me being ultra-cautious — the guys thought they had missed us, but they then caught us in the one-way system, by accident.

By that time we were half-relaxed. My very clear recollection, as in slow motion, was that I heard the bangs and felt the bullets hitting me. I was hit five times. Joe Keenan started screaming about Sean, because he was shot in the face.

I remember saying “Jesus Christ” or words like that, realizing very, very clearly that I had been shot, but that I was still alive. I said to Kevin to keep driving, to sound the horn. I said an act of contrition into Sean’s ear, while telling Kevin to drive through the traffic lights.

We drove to the Royal Victoria Hospital, and that was that.

Interesting thing was that a long time afterwards, I could hardly move my left arm. It was really sore. And the wound hadn’t properly closed (lifts up arm and gestures towards a bullet wound in upper, inside left arm), and wee bits of tweed started to come out of my arm — I had been wearing a tweed coat.

We went down to the hospital and it was X-rayed and I was told there was still a bullet there, a .45 round. The doctor sliced here. I haven’t a good sense of smell, but the stink was awful. The doctor poked out the round. The bullet was naturally working its way to the surface.

Sean was much more badly shot than me. But there’s a bullet wound here, at the top of my back, within a millimeter from the spine. The surgeon told me, a very nice man, that it went in and missed. He said it was miraculous.

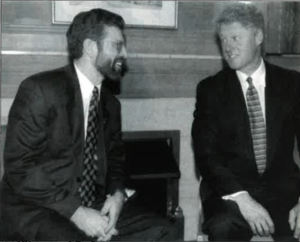

What do you think of President Clinton? What was it like to go to the U.S. for the first time?

The first time I went to the States was surreal because it was a 48-hour visa, so I didn’t sleep. People said I was very calm. I was actually asleep.

I have to say that I think Bill Clinton is a good guy. You might expect that. Obviously he’s a highly-skilled politician, and part of that is that you always feel you have his whole attention.

But I have spoken to him on many occasions, and I just know that on a number of issues he was genuinely engaged. Meetings went on far longer than his advisers wanted. He has a very deep and detailed grasp of the issues here.

What would be your ideal day off?

My ideal day — this sounds romantic — would be to wake up in bed with Colette and one of us would make breakfast and come back to bed, and just have nothing to do at all. No phone calls, just hang out, no agenda, no schedule.

Is music a big thing in your life?

Yes, absolutely. I play music all the time. I’m listening to Ry Cooder at the moment. I was always interested in folk music, English and Irish, Ewan McColl, Woody Guthrie…

I have a CD collection with everything from Fats Domino, through the Blues, into Leonard Cohen, Bob Dylan, light classical, opera. I sing rather unharmoniously.

Apparently you sing better than you drive, but not a lot better! (Adams’s reputation for being vocally challenged goes ahead of his own.)

There is a lot of jealousy in those remarks.

Do you have a party piece?

I know one verse of a million songs. I would like to be able to sing “Raglan Road” and a song in Irish “Mo ghile mear.” Tom Hartley and I do a duet of the Creggan White Hare which we once sang in the toilet of “B” wing of Belfast Prison and it sounded great, echoing throughout the entire jail.

If I go off walking, and become intoxicated by the day, and I’m fit, I come back singing away to myself with the exuberance of the day. I’m also a wonderful dancer, although there are people who begrudge that.

Do you enjoy food and drink, do you cook at all?

Yes. I cook most things. I like Italian food, pasta, meat and fish. I also like the occasion of a meal, sitting down and talking with friends, with a glass of wine. I drink more wine than Guinness these days. I regret that I didn’t discover wine earlier, Chilean, South African, Californian, Argentinian, French.

What’s your favorite county in Ireland apart from Antrim?

Donegal, but I’m biased in favor of every county. Every one has places of great beauty and one of the great delights of my life is travelling to see every county in Ireland.

I am always tickled by the fact that you go off any side road or boreen in Ireland and there’s a whole civilization there and life is going on as it has done for years.

Have you ever travelled outside Ireland on holiday?

Twice. Once by design and once by accident. I was going to Canada and was blocked at Amsterdam, so I spent a few days visiting Gerry Kelly and Bik McFarlane in jail, but I arranged for Colette to come out and we took the train to Paris.

A friend of ours lent us a flat and we spent ten glorious days in total anonymity. Colette says for the first five days she thought the Metro was a public lavatory because I wouldn’t use it — we walked everywhere. It was brilliant.

The other time, I was to go away for an award and we boxed off with another couple, who were supposed to be minders, and a friend lent us a little chalet in Switzerland for four days.

It was summer and good weather and the place was entirely the way it is in The Sound of Music. We walked in the high meadows and there was a woman ploughing a field.

You said in Before the Dawn that one of your first girlfriends was a Protestant. What would you say to her now?

Well, I wasn’t even conscious then of what a Protestant was. Some yahoo wrote a whole thesis on that comment saying it showed how republicans were colonizing Protestant children…

I have to say that I don’t know about that particular wee girl, but I have associates and friends who I bump into every so often from those days and we’re always glad to see each other.

What would you like your epitaph to be?

I wouldn’t be too concerned, because I won’t be here to see it. A worthy one might be “He did his best” and another, more acrid, would be “I told you I wasn’t well,” or “Don’t drive so fast.”

Editor’s Note: This article was originally published in the September/October 1998 issue of Irish America. ⬥

Leave a Reply