Irish history is littered with the names of emigrants who left to forge new lives for themselves throughout the world. Now, two special heritage centers are celebrating the lives of these emigrants, and their descendants have been given the chance to see where their grandparents and great-grandparents had their last glimpse of their native land.

The Queenstown Story

Their names were Peter, Jack, Nora, Maggie, Minnie and Kate, and one by one, the Sullivan children left Bounard, County Kerry, for Boston. They eventually made their way to Newburyport, where my grandmother, Minnie, married a Cork lad named James Barry.

In my eyes, the most fascinating souvenir of the journey was my grandmother’s trunk, mostly black, but embossed between the wooden slats with gold and maroon paper. Under the domed lid was a small painting of a girl in a boat. She was rowing across one of the Lakes of Killarney with Mac-Gillycuddy Reeks in the background, we were told.

In the mythology of the Sullivan family journey, the trunk was all that remained, and the rowing girl became a symbol of those who crossed the waters from Ireland.

Last summer, I finally went beyond the trunk, to Cobh, Co. Cork. There, at “The Queenstown Story,” where the story of Irish emigration is recreated in a stunning and evocative multi-media exhibition at the restored Victorian railway station, I felt closer to my immigrant ancestors than ever before.

Originally called the Cove of Cork, the picturesque Cork harbor town was renamed Queenstown following the visit of Queen Victoria to Ireland in 1849.

The port was the hub of naval and commercial activity. Tall ships called there in the 19th century to transport convicts to Australia and to carry emigrants to North America; later, transatlantic steamers and great ocean liners (including the ill-fated Titanic) embarked from Queenstown to carry the Irish to new lives in places throughout the world.

The numbers of emigrants departing from Queenstown (renamed Cobh in 1920), are staggering. Between 1800 and 1829, no fewer than 40,000 people left Ireland from Queenstown.

During the next decade, the numbers swelled to 84,500, and from 1840 to 1849, the Famine drove 239,000 more from the land. After the Famine, from 1851 to 1900, the population of Ireland fell from six million to just under four-and-a-half million and, as the “Queenstown Story” comments, “Emigration became an accepted pattern of life.”

Through a series of vignettes depicting conditions on board the ships of the time, the exhibition allows visitors to see what life was like on early emigrant vessels, including a 35-foot replica of the S.S. Servia and the convict ship The Atlas, which transported 153 men and 28 women to Sydney, Australia, in 1801.

With depressingly realistic audio-visual techniques — howling winds, plaintive cries, and disheveled figures huddled together against tattered bunks, tin cups and empty buckets — voyages from Ireland to the New World are depicted graphically and dramatically in a way that is both poignant and powerful.

In addition to the chilling portrayal of Irish emigration, “The Queenstown Story” also pays tribute to the special connection between the Titanic and the town, which was the liner’ s last port of call. The Lusitania, whose survivors were brought to Cobh by rescue boats when it was torpedoed off the Old Head of Kinsale on May 7, 1915, also features prominently. Many of its victims were interred in the Old Church cemetery near Cobh.

Because of its maritime and sentimental connections, the town of Cobh is a must-see destination for any visitor to the Cork area. Colorful shop fronts, a lovely seafront, and the imposing presence of St. Colman’s Cathedral all contribute to a delightful ambiance.

The Ulster American Folk Park

Large-scale emigration from the Northern Ireland province of Ulster to North America began as early as the 1720s when thousands of settiers sought a new way of life on the Appalachian frontier.

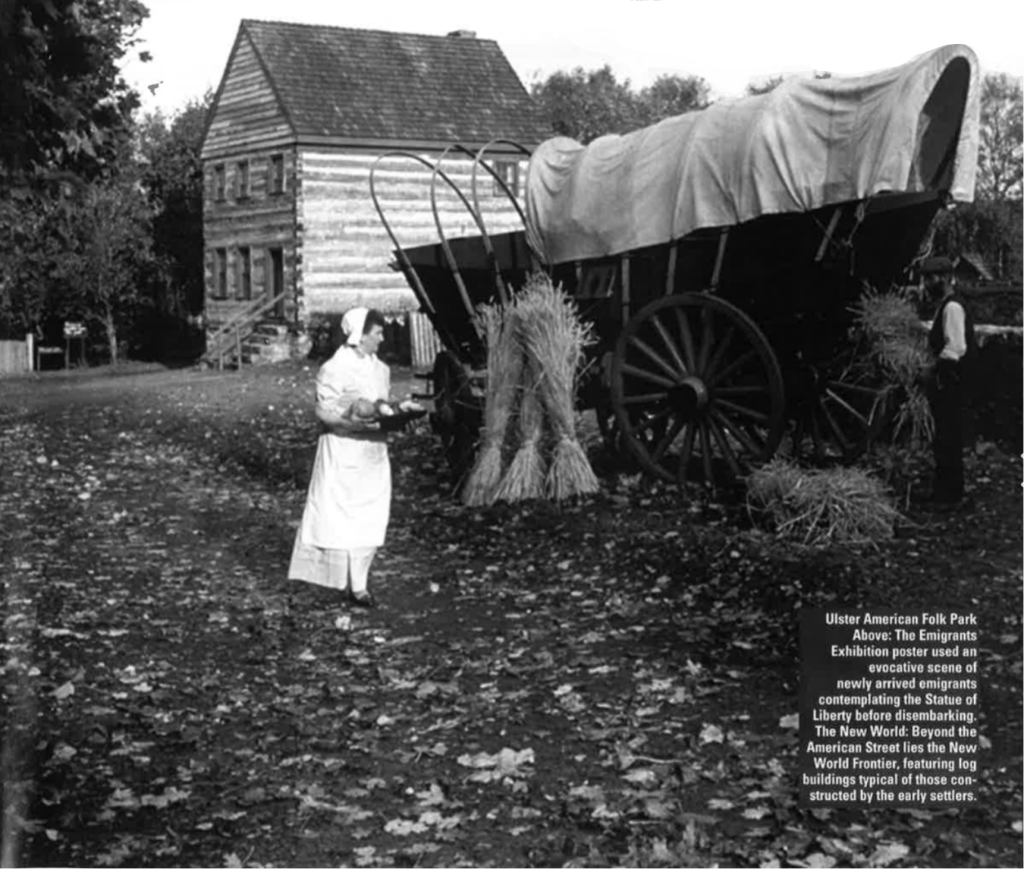

The Ulster American Folk Park in Omagh, County Tyrone, tells the story of these emigrants in a most unusual way. Unlike many emigration museums, the folk park is an outdoor living village that combines both original and replica buildings, first in the old-world Ulster setting, and later on the Pennsylvania frontier.

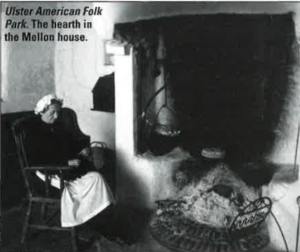

Much of the early development of the folk park evolved around the restoration of the birthplace of American financier Thomas Mellon, who left the village of Camphill, Co. Tyrone, in 1818 at age five.

Based on the detailed accounts of Mellon’s autobiography, which describe his life in rural Ulster and in 19th century Pennsylvania, the folk park was developed around Mellon’s boyhood home. Other buildings were rebuilt and relocated to the park, including a Famine cabin, blacksmith’s forge, weaver’s cottage, schoolhouse, Presbyterian meeting house, and a Mass house and the boyhood home of John Joseph Hughes, the first Catholic Archbishop of New York.

The “bridge” between life in rural Ulster and the world of Pennsylvania log cabin living is a dockside area that cleverly replicates the passage from Ulster to America.

Buildings on the Ulster side of the dock originally came from the three main emigrant ports of Belfast, Derry and Newry, and berthed in the dock is a reconstruction of an early 19th century ship modeled after the brig Union, which carried members of the Mellon family to America.

Visitors to the folk park actually board the vessel on the old-world side, walk through the steerage area of the ship and see how as many as 200 passengers and their belongings could be squeezed into the “‘tween decks” area, hear the sounds of the creaking timbers, and smell the foul odors of the emigrants’ living quarters.

Emerging on the new-world side, the visitor finds himself on a busy American street, possibly in the port of Baltimore, or Boston, or New York.

The most interesting features of the folk park are the costumed guides in each of the buildings who demonstrate what life was like in the homes.

At the Mellon Homestead, for example, cooking demonstrations are given; visitors to the schoolhouse can observe Master Patrick Mulligan giving a geography lesson; and in the Pennsylvania farmhouse and barn, visitors can see how early American woodcrafts were made.

Besides the interaction visitors have with the guides, there’s also a new permanent exhibition which tells the story of over 200 years of emigration using large-scale dioramas, color images, period stage sets, interactive computer displays, and a variety of original artefacts like quilts and clothing.

A major research center for the study of emigration is also on-site at the folk park, with an emigration database containing nearly 15,000 documents like ships’ passenger lists, emigrant letters, family papers and diaries. In 1994, a residential center opened offering accommodation for up to 38 people who wish to further study the unique phenomenon of Irish emigration.

Editor’s Note: This article was originally published in the September/October 1998 issue of Irish America. ⬥

Leave a Reply