He enjoyed a rapturous reception in London as a playwright until his conviction for ‘gross indecency’ in 1895 earned him a two-year prison term. Almost 100 years after his death, Oscar Fingal O’Flahertie Wills Wilde is again a huge hit with audiences. Darina Molloy examines his latest run of success.

It’s safe to say that Oscar Wilde would have loved the attention. After all, this is the man who once memorably wrote: “There is only one thing in the world worse than being talked about, and that is not being talked about.” The current surge in popularity of all things Wildean — be it books, movies or stage plays — is two years ahead of the centenary of his death, but then Wilde was never known for doing things by the book.

Two stage plays in New York, one of which transferred from London in April; a couple of books, one written by his own grandson; a movie starring a popular British actor/comedian; and a plethora of lectures and magazine articles are just some of the ways in which Wilde is being actively celebrated at the moment.

Though best remembered as a tragic figure who lost his family, his fame and his good name all for the love of another man — Lord Alfred Douglas (known affectionately to Wilde as Bosie) — Wilde is also deservingly heralded as one of the most talented wordsmiths in the history of literature.

The author of such bon mots as “I can resist everything except temptation,” and “What is a cynic? A man who knows the price of everything and the value of nothing,” he also appears to have had a touch of prescience when it came to his fate. Asked by a college friend what he planned to do after graduation, Wilde is said to have replied: “I’ll be a poet, a writer, a dramatist. Somehow or other I’ll be famous, and if not famous, I’ll be notorious.”

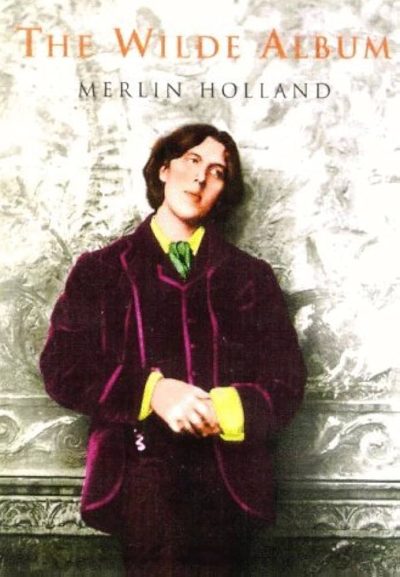

In The Wilde Album, Merlin Holland presents the reader with an enchanting history of his grandfather, from birth and ancestral lineage right through his life, trial, imprisonment, and sad, solitary death. The only son of Vyvyan, the younger of Oscar’s two sons, Holland is a noted Wilde scholar and lecturer, and has amassed an impressive collection of photographs, sketches, letters, and caricatures by and about his famous grandfather.

One of the most touching color slides in the book is of the scribbles of Wilde at 13, on an envelope in which he preserved a lock of “my Isola’s hair,” Isola being his sister who died at the age of 10 in 1867. There is a photograph too of the unusual wedding ring Wilde designed for his wife Constance and some rare snapshots of the writer’s last years in Italy. The narrative which accompanies the illustrations makes for addictive reading, and it is clear that Holland has inherited the family flair for words.

It’s just a little sad, however, that the family name was not handed down in the same manner. Wilde’s wife Constance and their two sons Vyvyan and Cyril were forced to change their name after being refused accommodation at a hotel in Switzerland, where they filed during Oscar’s imprisonment. They chose Holland, an old family name. A sentence on the book jacket notes: “The family has never reverted to the name Wilde.”

While Holland’s book is compelling, it is little more than an introduction to Oscar, one which will invariably leave the reader wanting more, much more. A suggestion: follow Holland’s excellent bibliography for additional reading suggestions, and keep an eye out for two new Wilde books by Holland, which are being primed for publication on the centenary of his grandfather’s death, November 30, 2000.

Juliet Gardiner’s Oscar Wilde: A Life in Letters, Writing and Wit is very similar to The Wilde Album in content and illustration, although Holland’s book is more attractively designed, and has the added appeal of being written by an author with an emotional investment in his subject.

A more serious examination of Wilde, and particularly his Irish roots, forms the basis for Wilde the Irishman, a collection of pieces by such writers as Fintan O’Toole, an Irish Times columnist and currently drama critic at the New York Daily News, playwright Frank McGuinness, and Nobel Laureate Seamus Heaney. The 17 essays explore Wilde’s Irishness in the context of his art, his politics and his gift of the gab. There is also an excellent excerpt from a play by Thomas Kilroy entitled The Secret Fall of Constance Wilde in which husband and wife meet for one of the last times.

Paula Murphy, an art history lecturer at University College Dublin, has contributed a piece detailing the erection of an Oscar Wilde statue in Dublin’s Merrion Square, across the road from the house in which he grew up. Wilde would surely have appreciated the gesture, and the unofficial christening of the bronze work. Writes Murphy: “Dubliners, with their traditional sense of irreverence and familiarity, instantly dubbed the work `the quare on the square.'”

Of the two Wilde plays currently running in New York City, it is surprisingly the off-Broadway production that is enjoying the longest run and attracting the better reviews.

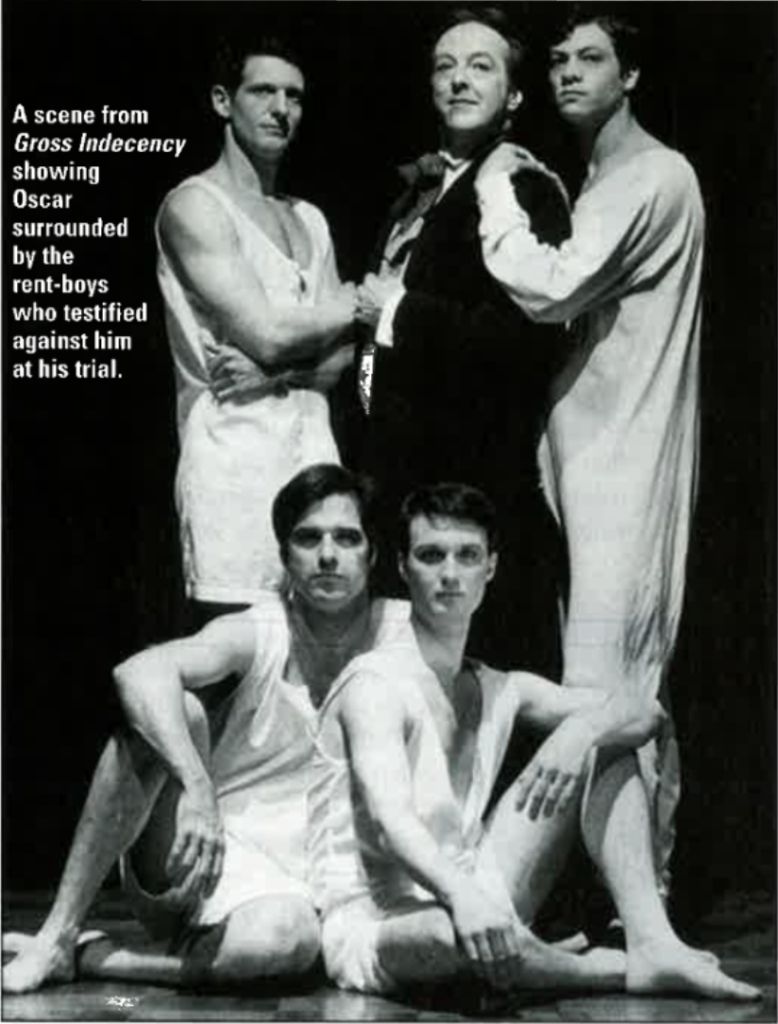

Gross Indecency: The Three Trials of Oscar Wilde, was first staged in New York in February 1997 to such acclaim that additional productions soon opened in San Francisco and Los Angeles. That the Manhattan production is still running, almost 18 months later, will come as no surprise to anyone who has been fortunate enough to witness this superb piece of theater.

Centered around the three court trials involving Wilde — the first of which he initiated in April 1895 against his lover’s father, the Marquess of Queensberry, who famously accused Wilde of being a “posing somdomite [sic],” with the tables turned in the second two, and Wilde himself on trial for homosexual acts — Gross Indecency is based on transcripts from the actual trials along with newspaper articles from the time, excerpts from some of Wilde’s work and various other sources.

The Judas Kiss, on the other hand, which stars Liam Neeson as a convincing Wilde, deals with two timeframes: the period between Wilde’s failed libel trial against Queensberry and his own trial for indecent behavior, and, in the second act, his shortlived reunion with Bosie in Naples after his release from prison. Although Oscar had resolved never to see Bosie again, and wrote as much in a long letter to the younger man which later became known as De Profundis, his resolve weakened and the two spent the summer of 1897 together in Italy. The play’s most searing moment comes when Bosie (played by Tom Hollander) turns to Oscar with an almost pitying sneer and declares that their relationship has been little more than “a phase” for him, that he is “not an invert,” and that his future holds a wife and children. “All I’ve ever wanted was your happiness,” sighs a dejected Oscar, “but in this, as in everything, our relationship is a failure.”

Gross Indecency, with its broader scope, fills the audience in even further with its pithy summing up: “After Wilde’s death,” a narrator declares, “Lord Alfred Douglas married and had two children. He became a Catholic, and eventually a Nazi sympathizer.”

Wilde the movie has the scope that neither of the two stage plays could hope to achieve, and tracks the playwright through his marriage with Constance Lloyd, the birth of his two sons, the zenith of his fame in London theater circles and, just as rapidly, the startling decline in his fortunes. British actor Stephen Fry offers a sympathetic portrayal of Wilde, a man clearly overwhelmed by his attraction to young Bosie. The film also shows another side to Oscar, however, detailing his prolonged absences from the family home which must have had a devastating effect on his two young sons.

For all its scope, or perhaps because it tries to tell too much of Wilde’s story, the movie is not as utterly watchable as Gross Indecency or as emotive as The Wilde Album.

As always, there is no better introduction to Wilde than a look at his own works. The Picture of Dorian Gray remains a classic, while De Profundis and The Ballad of Reading Gaol are a fascinating glimpse at the agony of a man tom between society and the “love that dare not speak its name.”

Editor’s Note: This article was originally published in the July/August 1998 issue of Irish America. ⬥

Leave a Reply