Deaglán de Brédún, Northern Editor of The Irish Times, watched history in the making in Belfast as voters turned in droves on May 22 to accept the Good Friday Agreement.

The Russian poet Vladimir Mayakovsky wrote of how strange it was to see trams running and everyday life proceeding normally although the Bolsheviks had taken over the government and begun a fundamental transformation of society.

The Northern Ireland referendum on the Belfast Agreement had that “Mayakovsky vibe” too. We were in the King’s Hall, on the fringe of Belfast, which had been used a short time before for an agriculture fair. There was a stillness and silence in the air.

Politicians and reporters wandered around aimlessly, their lives on hold until the magic figures were released.

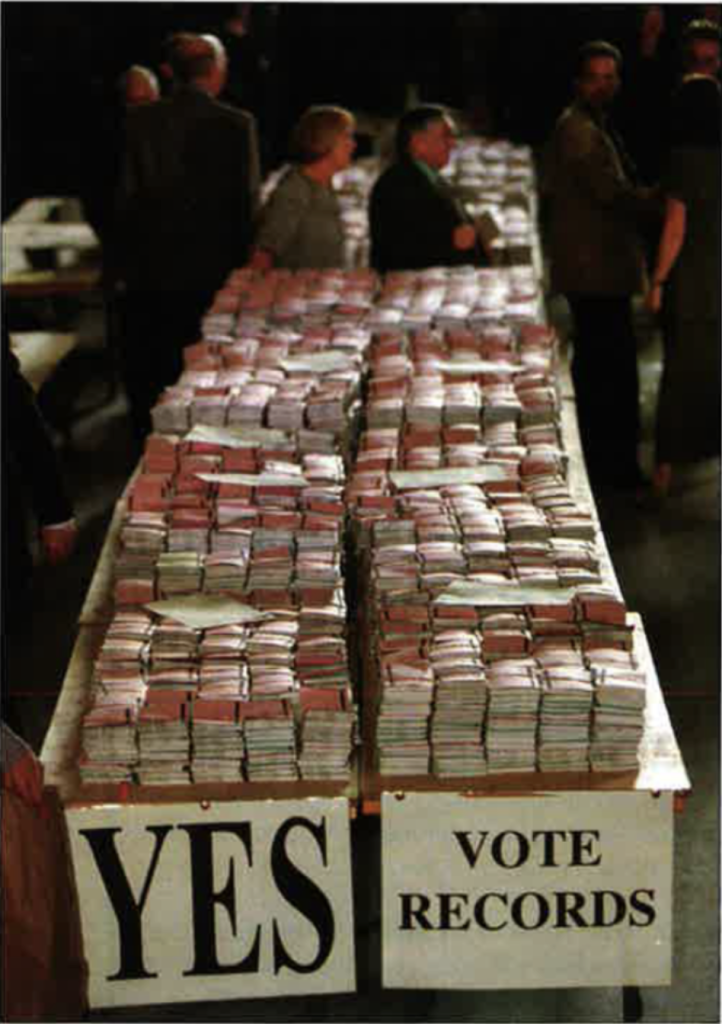

Election officials had erected a tall barrier to screen-off the vote counters so that even the narcotic diversion of watching the shuffle of the ballot papers was denied us. But it had been an exciting and tense referendum campaign.

Although the Belfast Agreement was always going to win, it was essential to get the support of a majority in both the Protestant and Catholic communities.

At heart, the Agreement is a pact between the two sides of the religious and political divide. The North will remain in the United Kingdom until a majority votes itself into a united Ireland. There are divided views on when that will happen — if ever. But in the meantime, the main party representing the Protestants — the Ulster Unionists (UUP) — have agreed to share power in a new assembly with nationalist politicians who represent the Catholic community.

In the bad old days of the Stormont parliament — a Protestant state for a Protestant people — nationalists were a largely disregarded minority firmly embedded in their status as second-class citizens. Now a system of checks and balances has been devised, to ensure that one community cannot override the other and all key decisions have cross-community support.

Opinion polls showed almost every nationalist from 19 to 90 was voting Yes but there was a big question mark over the sector of the population supporting the link with Britain. If sufficient unionists failed to vote for the Agreement, it would place UUP leader David Trimble in a difficult, even impossible, position.

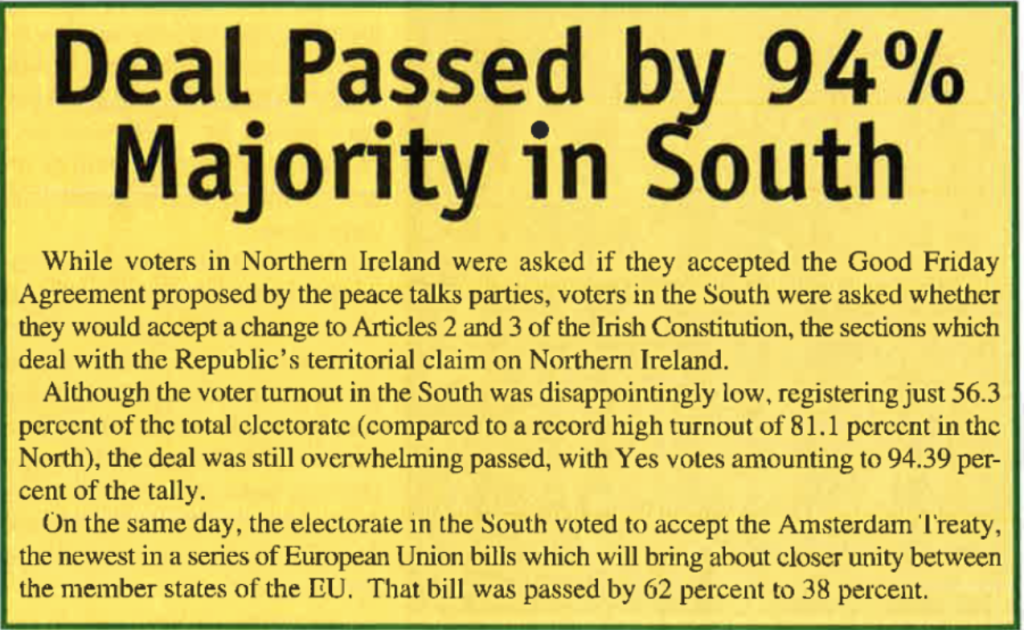

I wrote during the campaign that he was “fighting for his political life.” His party argued a Yes vote of 67 percent or higher would mean a majority in both communities supported the deal. The Democratic Unionist Party, led by the flamboyant preacher, the Reverend Ian Paisley, said if 26 percent or higher voted No, this meant a majority of unionists were opposed to the Belfast pact.

To settle the argument once and for all, the Agreement needed 75 percent support. A figure between 67 and 74 percent could still be claimed as a victory; between 60 and 67 percent would be less-than-ideal but ground might be recovered in the ensuing Assembly elections; Trimble himself admitted less than 60 percent would be “bad” and most observers believed it could be the end of him and the Agreement at the same time.

I followed Trimble for a time on the campaign trail. He went to the famous — or infamous — Derry walls which overlook the Catholic ghetto of the Bogside. Trimble was trying to reassure his followers the old order was still in place and had been consolidated rather than undermined by the Agreement. The subliminal message was, “We’ re still top dog.”

Struggling to keep my place, despite being elbowed and jostled by TV crews, I heard him tell his supporters that the Bogside was as British as Bournemouth or Bangor. Standing beside him was the Tory peer, Viscount Cranbone, longtime bête noir of Irish nationalists, whose unionist credentials would be hard to challenge. It was instructive to watch how Cranborne dealt with a DUP supporter who had been heckling earlier from the back. He listened with grave courtesy and assured the objector he knew where he was coming from. “There isn’t a cigarettepaper between us;” said Cranborne. But there was in fact a wide gulf: the Tory believed he was giving a little to save a lot, the DUP man was sticking to the old policy of “Not an inch.” Also accompanying Trimble was Kate Hoey, a County Antrim-born Labor member of the British parliament who takes a firm pro-unionist line. A colleague remarked that if the unionists had more like her — stylish, modern, articulate — they’d be doing so much better. Then again their constituents might have trouble accepting a modern woman.

To one side, a nationalist reporter grumbled that this was the spot where the Apprentice Boys organization traditionally threw pennies down on the Bogside as a gesture of contempt and domination. He also recalled that in the 1930s loyalists used to shoot at Catholics from this vantage-point.

When I discussed Trimble’s “photo-opportunity” on the Walls with a liberal-minded unionist later that day, he laughed heartily.

Sure, nationalists might be upset but they were “on side” for a Yes vote. The point of the exercise was to reassure the large bloc of unionists who were still dithering over the Agreement.

The following night there took place what may have been the decisive event of the campaign: the U2 concert. Word had leaked out over the weekend that “the boys” were heading North: The Irish Times revealed the plan in its Monday editions.

It was a risk for U2 but an even bigger gamble for Trimble. Here he was, about to go on stage with the uncrowned king of Irish nationalism, John Hume, and a rock band from the “Free State.”

There was distinct anxiety in the Trimble camp that some republican episode in U2’s past might be dredged-up and used to damage the UUP. Even this reporter was discreetly quizzed: it was like the old McCarthyite days in America — are they now or have they ever been fellow-travelers of republicanism? I laughed at this: U2 have traditionally been regarded as “unsound” on the national question and have irritated, even outraged, republicans with their iconoclastic stance.

But no doubt Trimble was thinking, as he walked on-stage at Belfast’s Waterfront Hall: this had better work. The main performers that night were Ash, a successful young band with a Protestant membership from Downpatrick. The kids lapped-up their offerings but to my medieval ears it was pure noise. I had to leave the hall for a while but full marks to Washington Post columnist Mary McGrory who lasted the pace better than I did.

A good proportion of the audience were young, middle-class Protestants. Maybe it was the darkness in the auditorium that gave them the courage but when Trimble and Hume stood side by side with Bono, the cheers were deafening. It seemed like one of those “defining moments” that the commentators like to write about. The kids seemed to be saying: “Right on!”

Trimble was the pivotal figure in the campaign and for the last couple of days before voting the ball bounced his way. He persuaded the former RUC Chief Constable, Jack Hermon, to accompany him on a walkabout. Tory peers, rock stars, ex-police chiefs: whatever type of reassurance you needed, Trimble and Company would supply.

Meanwhile, Lady Luck ceased to smile on Robert McCartney. A highly articulate lawyer, the UK Unionist Party leader was having a dream campaign until he bearded Tony Blair during a visit by the Prime Minister to Holywood, in McCartney’s own North Down constituency. Blair sped away in his limo and McCartney dismissed some women heckling in the background as a “rent-a-mob.” Outraged matrons confronted him on camera for his remark. It emerged later one of them was the wife of a former leader of the pro-Agreement Alliance Party. But at the time and no doubt to many TV viewers, it looked as if McCartney was being arrogantly dismissive of ordinary people doing their day’s shopping. The damage had been done.

And so, worn out from the marathon final stage of the Stormont negotiations and the ups and downs of a highly-fraught campaign, we found ourselves kicking our heels and taking bets on the side at the King’s Hall. “It’s 69, it’s 73…” The rumors fluctuated and politicians’ moods rose and fell in tune.

The final figure of 71 percent for Yes tallied with the opinion poll published in The Irish Times earlier that week. The SDLP’s Seamus Mallon, his eyes glistening, told me he thought it was the happiest day of his life. His party colleagues generally looked as if they had come into the land of Israel. Sinn Feiners, too, had broad smiles on their faces. From a balcony overlooking the hall, a Sinn Fein bigfoot observed Paisley being heckled by former supporters among the loyalist parties close to the UDA and UVF. As the loyalists sang “Cheerio, cheerio, cheerio!” at the aging DUP leader, the Sinn Feiner turned to a colleague of mine and said with considerable satisfaction: “Now, isn’t that a very interesting sight?”

Northern Ireland is still a helluva long way from normal politics, but it looks as if people are at last beginning to agree to differ.

Editor’s Note: This article was originally published in the July/August 1998 issue of Irish America. ⬥

Leave a Reply