With a 23-year theater career in Galway and Dublin, Garry Hynes is very well-known in her native Ireland. This year, New York audiences had the chance to get acquainted with the talented director.

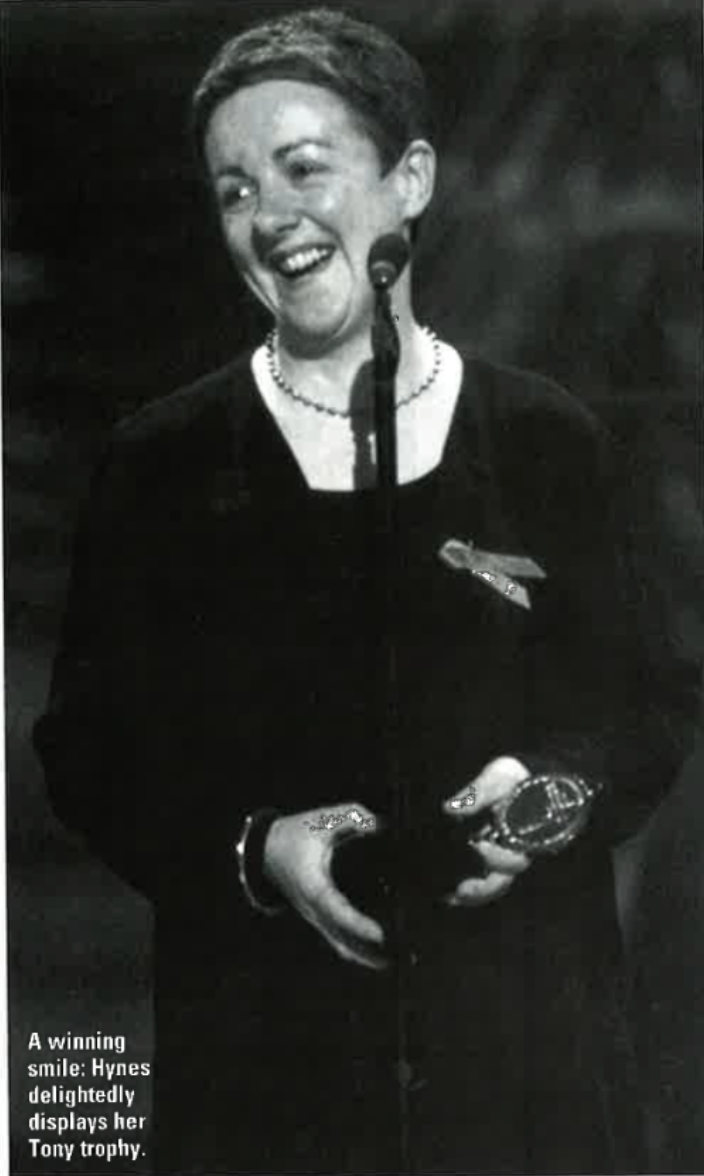

Two years ago, Garry Hynes took a chance on a young, unknown playwright called Martin McDonagh, staging his play The Beauty Queen of Leenane at Galway’s Druid Theater, which she had co-founded over 20 years earlier. This June, her gamble on Beauty Queen paid off handsomely when she became the first woman director to win a Tony Award — Broadway’s answer to the Oscars.

For the woman who first dabbled in plays at school, and found her true calling as a director soon after she started college, the prestigious award was the culmination of a 23-year career in theater.

In a heartfelt acceptance speech, Hynes thanked her family and the American theater community for the “warmth with which you’ve welcomed us.” She also broke into a few words of Irish when she paid special tribute to the people of Galway.

Hynes, as well as being dubbed “the woman who discovered Martin McDonagh,” also received the Lucille Lortel Award for Outstanding Director earlier this year. And during Beauty Queen’s run, she found time to direct her second Broadway play — the world premiere of Arthur Miller’s newest work, Mr. Peter’s Connections, starting “Columbo” actor Peter Falk.

A petite woman, whose close-cropped brown hair is attractively speckled with grey, Hynes looks younger than her 45 years, particularly when she smiles. She takes her work seriously and very much enjoys it, but also speaks longingly of periods between projects when she has the time to “hang out with friends,” read, and indulge in her “passion” for cooking.

Theater, of course, is Hynes’s main passion, one she first flirted with as a schoolgirl. “I remember doing a play when I was in national [elementary] school,” she reflects thoughtfully. “I don’t know why I did it, I must have gotten the idea from some book.”

Hynes has settled her home base in Dublin, where she bought a house in 1990. She hasn’t seen much of home lately, however, commuting regularly to Galway and London, and more recently New York. “It’s a bit of a nomadic lifestyle,” she agrees, but one that she enjoys and which holds “great opportunities.”

Born Margaret Gearóidín (Irish for `Geraldine’) Mary in Ballaghaderreen, Co. Roscommon, the eldest of four children, Hynes was re-christened by childhood friends after a TV series of the time, “The Adventures of Garry Holliday.”

Theater, she says, did not play a big part in her family, apart from the occasional “amateur play” her parents took the kids to see. “There must have been some kind of interest there from the beginning,” she ponders, “but I wouldn’t have seen more than half a dozen plays I’d say, at most.”

Her father’s teaching job led to a couple of moves for the family, from Ballaghaderreen to Monaghan, and then to Galway when Garry was 12.

Her parents, whom she credits with giving her support “in every possible way…both practical help and moral support,” still live in Galway, while the rest of the family is “scattered all over.” One brother, Donal, is a doctor, married with a family in Somerset; Jerome is the chief executive of the Wexford Opera Festival; and Garry’s sister just recently moved to San Francisco, where she works in public relations in the computer industry.

It was when Hynes began studying English and history at University College Galway (UCG) in the early 1970s, that she became involved with Dram Soc, the college’s drama group, “and that’s basically what I did for the next three or four years.”

Drawn to directing from day one, she says she never considered acting. “I knew I couldn’t act. I hadn’t tried but I knew it was something I didn’t want to do, it didn’t strike me as something enjoyable to do. I wasn’t quite sure what directing was but it sounded a bit more interesting, so I started directing and that was it for me.”

Hynes has spoken candidly of her virtual abandonment of her college studies in favor of more time with the drama group, but her parents, she says thankfully, did not attempt to dissuade her from her chosen path.

“They were very good about it,” she smiles. “Basically when it became clear that I was taking it very seriously, and I told them I wanted to go on doing plays they said, `Fine, it’s a terrible life but go ahead, as long as you just get educated first.’ So as long as I got my primary degree, which I did, they were happy to let me go really.”

In 1975, Hynes and two other UCG alumni, actors Mick Lally and Marie Mullen, launched Druid with an inaugural production of J.M. Synge’s Playboy of the Western World. What started as a summer project for three college graduates blossomed into a hugely successful company. It is now the third-largest theater company in Ireland and Hynes is artistic director.

“When we started Druid there wasn’t any theater outside Dublin and now there isn’t a town [in Ireland] without a festival or an arts center or a theater,” she says. “I like to think that it’s a sign of the health of the company that we continue to achieve, to push forward and to go for new challenges now as much as we did ten or 15 years ago.”

As a student, Hynes had “no interest at all in Irish culture or Irish plays,” a common enough characteristic among that age group. Instead, she concentrated on the work of American playwrights, whom she grew familiar with through summers spent in New York. David Rabe was a favorite, she says. Once the decision to form Druid was made, things changed.

“We chose Playboy for our first production because we were starting off in the summer months [and felt] we should provide something that would appeal to a tourist audience. So we decided on Playboy but most of us had a school or university take on it — that basically it was this old-fashioned play.

“It was when we were about halfway through rehearsals that all three of us decided `If we survive, we’re going to do this play again, because it is such a fantastic play.’ And that’s exactly what we did do three years later, and [again] in 1982.

“So that was the start of it and I realized that Synge is the most extraordinary writer in the English language. From then on I became interested in other Irish writers-MJ Molloy, and then the more contemporary Irish writers, in particular Tom Murphy.”

When Hynes discusses her favorite playwrights, a slight reverence creeps into her voice and she refers to the “great privilege” of working with writers. What she doesn’t volunteer until asked, however, is that she wrote two plays in her early Druid days. Not out of any great desire to be a writer, she insists, but simply because “the new plays that were being sent to us weren’t any good.”

Her love of history came to the fore in both plays, one of which was about Oscar Wilde, the other a fictionalized version of a real-life encounter between Irish prate queen Granuaile (pronounced Grawn-you-ail) and British Queen Elizabeth I. Twenty years after she penned her dramas, there is talk of a movie deal about the infamous West of Ireland queen of the high seas following the rerelease of a book by Irish author Anne Chambers.

Despite a remark by Irish Times writer Fintan O’Toole at the time that Druid’s production of Hynes’s own play about Granuaile was “the future of Irish theater” — Hynes insists that unlike many other directors, she just wants to direct.

“I’m an interpretive artist, so to speak, rather than a primary artist. A lot of people do both successfully, but I’m just not one of them,” she says firmly, in a tone of voice that brooks no argument.

In Ireland, Hynes is as well known for a controversial three-year stint in the early 1990s as artistic director of Dublin’s Abbey Theatre — the Smithsonian of the Irish theater world — as she is for her long career with Druid. Criticized for her unorthodox interpretation of certain plays, she admits the Abbey experience was not all she would have hoped for.

“I never had the slightest regret that I did it,” she hastens to add. “I think it was very impressive for me and I learned a lot from it. I can say I’ve had the privilege of being artistic director at the Abbey. At the same time I found the time there frustrating because I found an organization that simply was unwilling to change.

“I was prepared to go into the Abbey on the basis that there be an understanding that while change is difficult and must be taken slowly, it must happen. That really didn’t exist and I eventually felt that I no longer had anything to give in those kind of circumstances so I finished my contract and left.”

Was her rocky tenure at the Abbey partially due to the fact that she’s a woman director? “Obviously at that kind of level the gender issues become a little bit more problematic and I don’t doubt there might have been a small element of that, but it wasn’t the fundamental problem,” she replies.

Back at the Druid, having taken a one-year break after her tenure at the Abbey, Hynes turn her attention to a pile of new scripts which had arrived at the Galway theater. One challenge which Druid has long been noted for is the company’s willingness, eagerness even, to showcase work by new playwrights. Hynes calls this “the single most important thing…the lifeblood of the theater.”

It is therefore fitting that Hynes was the first director to take Martin McDonagh seriously, after he had been rejected elsewhere. With typical modesty, she deflects praise of her directorial vision. “I feel sure Martin would have been produced at some point, because talent will out, and he is a very great talent,” she says matter-of-factly.

When we started Druid there wasn’t any theater outside Dublin and now there isn’t a town [in Ireland] without a festival or an arts center or a theater,”

After several theater companies in Ireland and Britain famously rejected McDonagh’s submissions, what convinced Hynes that The Beauty Queen of Leenane was, in her words, “a bewitching but bewildering” piece?

“It was clear reading a few pages that Martin has great dialogue which, oddly enough, a lot of writers are not so good at,” she says. “The other question was whether he could create characters and tell a story and by the end of the play it was very clear that he could do all three.”

When word began to spread about the startling Druid production of Beauty Queen it led to a co-production between Druid and London’s Royal Court Theater which saw the show performed simultaneously in England and Ireland.

American producers began to show interest and earlier this year, Druid made the move to New York, running for a month off-Broadway to tremendous acclaim and transferring to the Walter Kerr Theatre on Broadway in April.

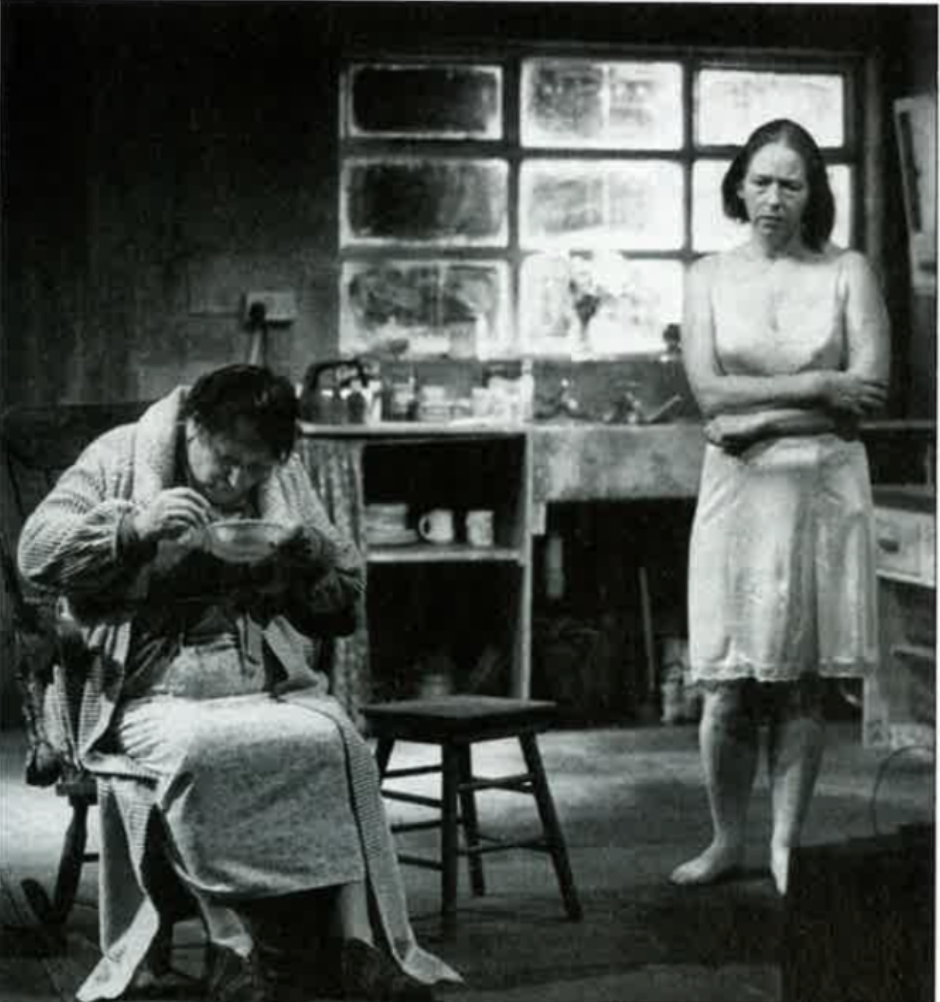

A London production of another McDonagh play, The Cripple of lnishmaan, was also picked up and was produced off-Broadway earlier this year with a mostly American cast to mixed reviews. Hynes is delighted, however, that when Beauty Queen was brought to the U.S., she succeeded in retaining the show’s original Druid cast — Anna Manahan as the domineering Mags Folan; Marie Mullen as her put-upon daughter Maureen; Brian F. O’Byrne as Maureen’s hapless suitor Pato Dooley; and Tom Murphy as his younger brother Ray. Four Tonys — including one apiece for three of the show’s four actors — is proof that she was right to stick to her guns.

“The biggest thing with Druid has been that it’s a company of actors,” explains Hynes. “The fact that the entire company was nominated kind of captured the spirit of Druid. The ensemble nature of the company is extremely important and to have that recognized in the most competitive entertainment arena in the English-speaking world is very, very satisfying.”

Although some observers expressed disappointment that Beauty Queen was pipped at the post for the Best Play award, Hynes told the Irish Independent that playwright Martin McDonagh was bound to win that honor at some stage in the future. “To be sure we were disappointed,” she said, “but to talk about disappointment after winning so much is tempting the gods. And I don’t think not winning will matter much to Martin McDonagh: he’s certainly going to be back here with other plays and next time he’ll win.”

Being known as a director who nourishes new writers does have its drawbacks, however, and Hynes grimaces, only half in jest, as she describes some of the unsolicited manuscripts she has received. “For every hundred plays written, 98 are dreadful. Not bad or not just `not good,’ but dreadful. So it’s difficult.”

Does she receive a lot of manuscripts from Martin McDonagh wannabes? “Oh yeah, constantly,” she laughs. “Sometimes you think everybody in the whole country is sending you plays.”

It was another Martin McDonagh play, The Lonesome West which drew Arthur Miller’s attention to Hynes’s directing skills.

Miller, of course, is widely regarded as one of America’s greatest living playwrights, and Hynes speaks fondly of her time spent working with him, describing him as “extraordinary…wonderful to work with,” and “a genial, decent, intelligent man.”

Explains Hynes: “Arthur came to see The Lonesome West last summer [in Galway] and apparently rang his agent and said ‘I’ve found a director for my play.’ A couple of months later, I was sent a script and I was asked if I would consider doing it.” She rolls her eyes jokingly as if to say “What’s to consider?”

Does she think actor Daniel Day-Lewis, who is married to Miller’s daughter Rebecca, had any hand in recommending her? “Undoubtedly,” she nods. “I don’t think [Miller] would have been in Ireland otherwise. He was in Paris at the time and came through Ireland because Rebecca was there with Daniel. Apparently they had seen the play and said to him, `You should see this.'”

Although Mr. Peters’ Connections-which finished its ten-week run in June as part of the Arthur Miller season at Manhattan’s Signature Theatre — received a mixed bag of reviews, there was also a sense among some critics that Hynes did a good job directing a difficult play. Fintan O’Toole, the transplanted Irish Times columnist who is currently working as a drama critic for the New York Daily News, praised Hynes’s unfolding of the play “as a bluesy trumpet solo in which the underlying note of elegy gives way from time to time to witty riffs on the American past.”

So what does the future hold for Hynes? She says she’s never been able to answer that question. She does know that she intends to continue her work with Druid and says she is “looking forward” to the possibility of more work in the States. “Obviously the success of [Beauty Queen] is opening up more opportunities for me,” she admits. “I’ll just see what comes along.”

She also confesses to a long-held ambition to make a film, but adds that she’s never given enough time to developing the idea. One suspects from her quiet determination that she’ll get around to it in her own good time. In the meantime, she’s hoping to take a short break, giving herself the chance to indulge in her three favorite pastimes — cooking, reading and traveling.

The woman who likes to take chances on young, untested playwrights also loves nothing more than a good game of poker. Is she any good? “I’m supposed to be, yeah,” she grins, her eyes sparkling. What kind of stakes does she favor? “I like to play for serious stakes,” she says. “I don’t think you can play a friendly game. Martin [McDonagh] is a good player. I taught him and now he’s better than I am.” That modesty again.

Anything else interesting in the works? Like any good poker player, she’s not going to reveal her hand until the tune is fight. “I have a couple of projects under review,” she says casually, but that’s as much as she’s willing to reveal.

Editor’s Note: This article was originally published in the July/August 1998 issue of Irish America. ⬥

Leave a Reply