Two years ago Aimee Mullins made her Olympic debut as a member of the U.S. Paralympic Team at the Atlanta Games. She set world records in the 100-meter dash and the long jump. Darina Molloy spoke to Mullins, a double amputee, about her sporting achievements, her burning desire to “mainstream” disability, and her plans for the future.

Aimee Mullins has already packed more into her 22 years than many people twice or even three times her age have achieved. Olympic athlete, model, dean’s list student, public speaker…she’ll try anything at least once, and the fact that she is a double below-the-knee amputee is almost incidental.

Born without fibulas, the long bones connecting the knees to the ankles, Mullins had both of her lower legs amputated as a baby after doctors told her parents it was her only shot at eventually being able to walk.

Once the young Aimee mastered the art of getting around on prosthetic legs, there was no holding her back as she plunged headfirst into every sport that took her fancy. Baseball, soccer, frisbee, skiing, she was game for “anything that involved running and jumping.”

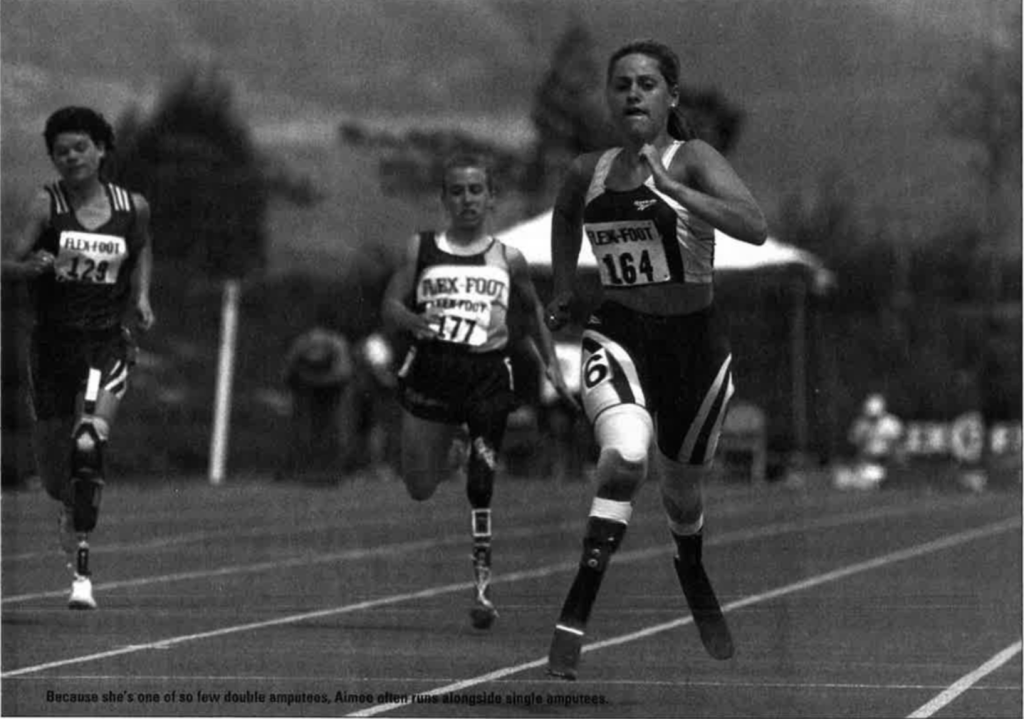

In 1995, Mullins decided she wanted to run track and began competing at meets throughout the country. Just over a year later, a testament to her incredible drive and determination, she was a member of the Paralympic Team at the Olympic Games in Atlanta. She holds world records in both the 100-meter and 200-meter dash, and the long jump.

This May, she graduated from Georgetown University with a double major in history and diplomacy. As with her athletic achievements, Aimee aimed high at school, and was one of only three scholars in the nation in 1993 to receive a full academic scholarship from the U.S. Department of Defense.

While combining college classes, term papers and regular tests with the rigors of athletic training and track meets, she also found time to travel around the States fulfilling various public speaking engagements. She hates the word motivational, but it’s a term that has frequently been used to describe her impact on others.

Her main goal is to help break down the awkward social barriers that afflict people with disabilities. “We have this conception in society that being disabled means you’re `less able,’ you’re less attractive, less competent, less intelligent…less everything,” she explains. “I’m sort of putting myself out there and showing as much normalcy as possible.”

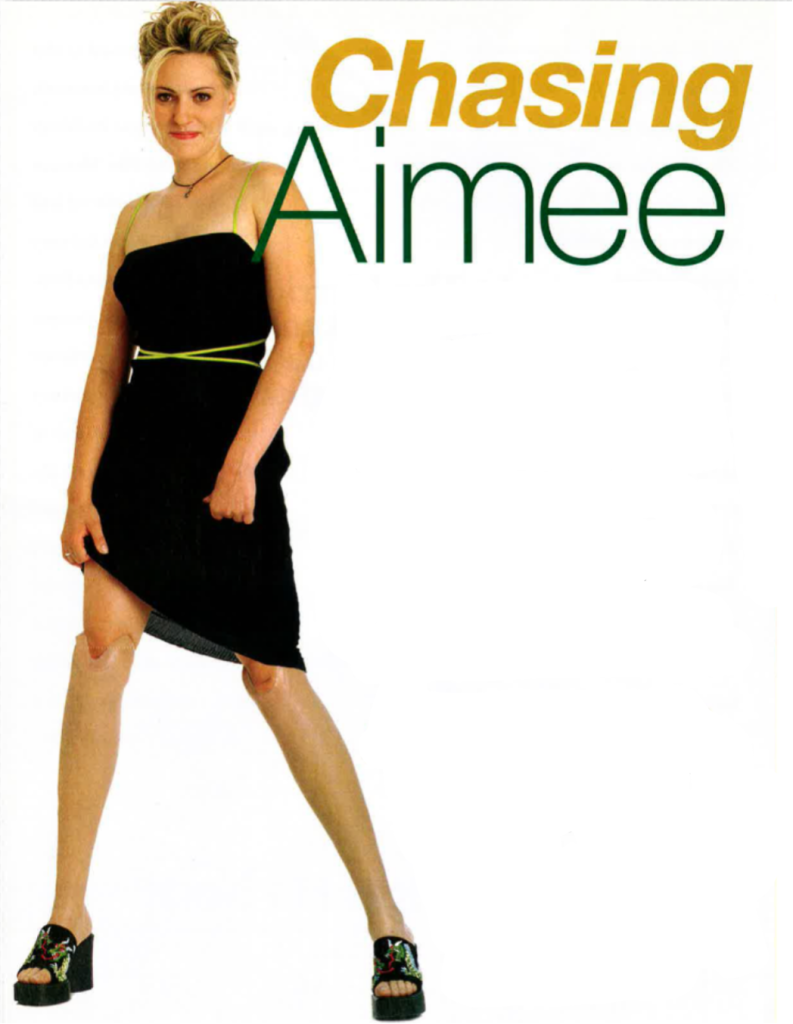

We meet on a beautiful, sunny May morning in Georgetown, the day before Mullins is due to graduate. She is a flurry of activity, rattling off a list of things she has to get done before her family arrive en masse from Allentown, Pennsylvania that evening. Elegantly casual in a kimono-style black print dress, with her blond hair twisted into a loose bun, she gestures constantly as we drive through the picturesque D.C. college neighborhood, raising her hand off the steering wheel to point out the college, her apartment, a house where the young John F. Kennedy once lived.

The first thing you notice about her is that she talks a mile a minute, her face lighting up animatedly as she flits from one topic to the next.

The second and third things you notice are her legs: they’re perfect.

From the slim ankles tapering down underneath the end of her dress, to the perfect size 7 feet encased in open-toe sandals, Mullins looks every inch the model. She giggles delightedly at my awed admiration, and yanks her skirt up a couple of inches so she can show off her realistic moles, veins and hair follicles. “They’re great, aren’t they?” she exclaims proudly of the prosthetic limbs that begin where her own legs end, just below the knee.

For running, Mullins switches to a second pair of cat-like carbon graphite sprinting legs which resemble upside down question marks, and for days when she’s just hanging out or doing chores, she straps on a pair of very high-tech looking, shock absorbent, robot-like limbs.

Born July 20, 1975, in Allentown, Pennsylvania, Aimee Erin was the first child for Clare man Brendan Mullins and his American wife Bernadette (née Anthony).

Doctors told the young couple, who had been married just under a year, that without fibula bones, their daughter would never walk: her lower legs would not be strong enough to support her body weight. Seeking alternatives, the Mullinses were told that Aimee might avoid being confined to a wheelchair if her legs were amputated below the knee and she was fitted with prosthetics. A series of operations followed, the first on Aimee’s first birthday, the last when she was eight.

“When they gave me her first pair of legs, they said Aimee should be walking within a few weeks,” recalls her mother, Bernadette. “But the legs were very heavy for her, and three weeks later she couldn’t stand up on her own, or even crawl properly. I was frantic – the doctors just didn’t realize how much we were hanging on their every word. When she walked, finally, at around sixteen and a half months, we were just delighted that she was able to get up and go.”

Aimee acknowledges that the whole experience was probably quite traumatic for her parents, but adds: “That’s something we’ve never really talked about. It’s just sort of accepted that that’s what happened. My parents never sat me down and said, ‘God, it was just so awful to make this decision [about amputation].’ It was just ‘Get your legs on and get dressed.'”

She describes her earliest legs as being more clunky than what she’s used to now. They were made of a wood-plastic composite and were attached to her own limbs with velcro straps. “It was all I knew at that point, and it wasn’t like it was tremendously uncomfortable, but they were a lot heavier,” she says.

When it came to awkwardness from other kids at school, Mullins learned at a very young age how to deflect the teasing that kids tend to inflict on anyone `different.’ “I realized that if I made jokes about my legs first, then it wasn’t some sort of taboo thing,” she says. “Plus I started with these kids so young that it was really normal for them — I mean sometimes they would forget. It could be really cold out and I would have shoes on that wouldn’t be insulated, and my friends would say, `God, aren’t your feet cold?'” She giggles as she remembers their embarrassment when they realized what they had just asked.

Her parents also tried to protect Aimee as much as they could. “That was Brendan’s job,” says Bernadette with a laugh. “We have always tried to be very positive in all the things that have happened, and we also had very good family support.”

A large circle of cousins on her mother’s side (Bernadette is one of 11 siblings) living nearby meant that Aimee and her two younger brothers, Thomas (now 19) and Brian (16), were constantly attending various family gatherings where the kids were encouraged in all kinds of activities. As the others played soccer and baseball, Aimee threw herself right into the fray.

“She was never one to sit around and watch TV,” remembers Brendan, who works in the industrial maintenance department of CR Beatings and Seals, a company which manufactures ball bearings and sealants used in the construction of airplanes. “She was always independent, always running around playing softball, baseball, and going bowling and swimming.”

Growing up just outside Allentown, an area with a generous distribution of Dutch and German immigrants, but not so many Irish, Aimee says regular summer trips to her dad’s family farm in Crusheen, Co. Clare kept the family’s heritage in the forefront.

There were also the annual March 17 pilgrimages to New York City an hour-and-a-half away, when the Mullins kids and their parents would pile in the car and head for the longest-running St. Patrick’s Day Parade celebration in the world. On years they couldn’t make it, they would all troop along to what she describes as the “dinky” local festival in Allentown.

There was a time, says Brendan, when the family were seriously considering moving to Ireland. “For my own sake, I’ve regretted [not moving back] many times, but for the kids’ sake I’m glad I didn’t. This is the best country in the world for opportunity, you’re only limited by your own limitations.” In terms of medical care for Aimee, the States also proved the best place to be, and Brendan says an Irish doctor advised them to stay put.

Brendan may have raised his kids with an emphasis on the Irish side of their heritage, but Bernadette, whose four grandparents were Austrian, got her own back last Christmas with her choice of gift for her daughter. Aimee laughs as she recalls the selection of CDs Bernadette presented to her — a dozen collections of Austrian and Viennese music. “She just said, `You’ve never been exposed to this side of things, here it is.’ And the funny thing is, it’s my father who loves that music, he’ll play the waltzes over and over again.”

Aimee is close to both her parents, and likes to think that she has inherited her mom’s “incredibly trusting” nature and her dad’s sturdy determination.

“My father often said if he was taken into a POW camp they’d never break him because his will was too strong,” she remarks. “I’m very much like that too. It sounds ruthless, but if I want something, I make it my priority to figure out a way to get it done.”

Brendan Mullins also constantly stressed to his kids the importance of education, encouraging them to take advantage of the school system in the States where, unlike Ireland, college entry does not hinge on a single set of exams. By age three, with her mother’s help, Aimee was able to read. At school, she says, straight A’s were not so much demanded as simply expected. “I was seriously raised with the attitude that `Not only can you, but it’s expected of you,'” she says. The unspoken message to the young Aimee was clear: you can do anything.

Well, she clarifies, almost anything. “Emotionally there’s nothing I can’t do. There’s things that I’m afraid of, but I never say I can’t do them. Physically…I can’t do ballet. I can’t bend my ankles. If they make a leg where I can do that, then I will do that.”

In 1993, Mullins started studying International Affairs at George Washington University. After two-and-a-half years, she transferred to Georgetown University where she continued to study history and diplomacy, her twin majors. As part of her scholarship from the Department of Defense, she spent four summers working at the Pentagon. She now says that a career in government is not something she wants to pursue right away.

“I could see myself coming back to it,” she reflects. “In fact, I was talking to the president of my university about it and he said, `Aimee, don’t rule it out. Just see yourself in 30 years having a nice spot in the Embassy in Dublin, you’d be very happy.’ And you know what? That sounds about right.”

In the interim, she has a long list of things she wants to accomplish. In 1995, deciding on a whim to see if she could run, she signed on to compete in a meet for disabled athletes. “When I ran that first race in Boston, the 100 meters,” she recalls, “I had yet to complete a full 100 meters.”

Sports Illustrated for Women documented Aimee’s story last fall in a nine-page photo essay. In 1996, competing against able-bodied runners at her fast inter-college meet, she ran the 100 meters in a personal best of 16.70 seconds. Over the next 12 months, her times dropped to 15.77 in the 100 and 34.06 in the 200 meters. Both times are unofficial world records in the amputee class, and Mullins, running for Georgetown, was the first disabled member of a Division 1 track team.

A note of pride creeps into her voice as she sums up her achievement. “In June 1995, I was a college student on her way to a Pentagon job, and basically a humdrum existence, until I decided to take control and try to become an Olympic athlete. And within a year and three months I was there.”

It’s the experience I’ve had with my legs that have shaped me and I want to use them in ways that people would never have thought to use them before.”

The Atlanta Olympics proved a turning point in Mullins’s life. She knew that she would be competing against single-leg amputees, but twenty minutes before the 100-meter race, while on the warm-up track, she discovered that Paralympic rules meant she would also be running against hand amputees. For someone who was used to winning, it was a devastating blow. Her face hardens as she remembers how gutted she felt.

“Going into this, with my entire family having driven 800 miles to be in the Olympic stadium, and knowing that I was going to lose, I mean it was…” she trails off, struggling to convey the depth of her emotion. “Devastating wouldn’t even describe it properly. Just knowing that you would either have to go through with it, or face death at that point, that was the most humiliating, humbling and ultimately empowering experience I’ve ever gone through in my life. It was the hardest thing I’ve ever done.”

She doesn’t remember much about how she forced herself to run that day, but she does remember the song that was playing in her subconscious. “I walked onto the Olympic stadium and the beginning of that U2 song `Pride (In the Name of Love)’ was just building up in my head to a crescendo,” she says.

“I felt like I was going to throw up, and it was like: ‘Here it is, this is your life. This is what you got yourself into. Now do it.’ Ultimately, I finished last, and I had never lost anything before.”

Although she lost the race and failed to medal, Mullins did succeed in setting an unofficial world record in the double-amputee class for the 100-meter dash and the long jump. She also won far more at Atlanta, she says. “It’s just a sense of peace I have now. I mean I’m still incredibly driven, but there’s just much more of a sense of peace about it.”

It’s understandable if Mullins’s brush with red tape at Atlanta put her off competitive running. The scoring rules will change for the Sydney Games in the year 2000, she explains, but she is evasive about whether she plans to compete. Her knees have been giving her trouble lately, and until doctors are able to pinpoint what might be causing the problem, she’s not too interested in getting back on the track.

“I wanted to see how far I could take it,” she says of her athletic career. “I sort of had this challenge in mind of trying to get to the Olympics and I went for it at full speed. So for me, the thrill is not running per se, it’s competition.

“Basically, what it all boils down to is when you realize, and admit to yourself, that you’re really afraid of something — whether it’s strapping on a pair of running legs and competing in public or whatever — but you do it anyway. Because you can feel yourself getting stronger.”

She’s also quick to point out that being an athlete “is only a percentage of who I am. That’s not who I am in total. To me it’s a verb. I did athletics. I did that for a while and now I want to do modeling, do acting. So I’m not going to call myself a model or an actor or an athlete. You can’t be limited by that.”

Life after Atlanta took a dramatic turn for Mullins. All of a sudden, her story exploded onto the public domain and she was hotly sought after by magazines and documentary film crews from a multitude of networks.

In 1997, NBC’s popular “Dateline” show aired a 20-minute segment about her. “Oh we got mail from all over the world after that show aired,” Bernadette remembers.

The attention she received after her Olympic debut served as a two-fold platform for Mullins: it gave her the opportunity to focus a large, public spotlight on disability, and it also gave her a taste of a life she would very much like to explore further.

“There are some things I do that are on the platform for greater [social] awareness and there are other things I do that are just for me,” she admits. Her foray into the world of modeling, she says, is both. “If a twelve-year-old girl sees a picture of me and says, `Well, if that’s considered beautiful, maybe my nose isn’t so bad, maybe I don’t need to lose those ten pounds, maybe what makes me the ugly duckling really makes me the swan.’ At that level it’s about creating awareness.”

She’s also candid enough to admit that she likes the glamour, likes the traveling opportunities her various engagements have afforded her, and craves the long-term financial stability that such a lifestyle offers. “If you’re smart, what are you going to do?” she asks rhetorically. “Not use your brain to get you where you are? You use it, otherwise you’re just wasting yourself, you’re letting yourself rot.

“It’s the experiences I have had with my legs that have shaped me and I want to use them in ways that people would never have thought to use them before. So in that case, a lot of the artsy stuff I want to do with my legs, that’s for me.”

She readily accepts that she may come under fire from other people with disabilities for “exploiting” her legs, but she’s ready to face the flak. There’s already been some criticism, she says, along the lines of how “lucky” she is that things fell into her lap.

At this, Mullins explodes. Clearly, such comments infuriate her. “I was like, `Where have you been the past three years? I worked my ass off for this.’ Most people would have a nervous breakdown if they had to deal with all the stuff I’ve done in the past three years.

“Why can’t [some disabled] people admit the fact that they would never want to show their legs themselves and they’re uncomfortable with somebody who can?”

Aimee not only wants to show off her legs, she wants to use them in as many different ways as possible and she is bursting with ideas for creative advertising campaigns which would involve her sporting a snakeskin leg, or a leg created for an African-American woman, or a glass leg. “There’s so much you can do with design,” she says with infectious enthusiasm. “Can’t you just picture how great it would be?”

She is adamant, however, that the word “disabled” should not be tagged on to her name. “There’s a modeling agency in New York that just deals with disabilities, but I don’t want to be limited by that. You know, `We need the disabled model, call her,’ that kind of thing. This isn’t so much about a crusade of mine, this is also about me. I was raised in an able-bodied world.”

It’s not all about herself, however. Bernadette, who works both as an observer attendant with psychiatric patients at the local hospital and as a transaction processor for Guardian Life, quietly points out that her only daughter has helped many other patients facing amputation, either visiting them in person or talking to them on the phone.

Four months ago, Aimee joined forces with her trainer Steve Kostorowski and his wife Sue to establish a non profit organization called HOPE (Helping Other People Excel). Through HOPE, she hopes to raise funding for centers and equipment for other disabled athletes. “It won’t be about teaching people to walk or anything, it’s beyond that,” she explains. “This will be for an eight-year-old Aimee Mullins who’s running around playing softball and doing everything.

“We’re going to raise money to buy legs, wheelchairs, socket liners, whatever people need. Insurance won’t pay for these things, so our ultimate goal is to have HOPE centers in major cities outfitted with training facilities accessible to wheelchair users.”

It’s an expensive business, and nobody knows this better than Aimee. Her “pretty legs,” which she picked up last year from a prosthetic company in Dorset, England, cost about $8,000 per leg. As a functional work of art, they’re more than worth that price. The legs were designed with an arch which needs a 2-inch heel, and Aimee needs footwear of that height to maintain her balance. The same company, Dorset Orthopedic, is also working on another pair of legs with which she will be able to wear flat shoes or just go barefoot. She’s hoping to have those by the end of the summer. With the pretty legs, she got to pick how tall she wanted to be (“within reason,” she clarifies) and what size feet she wanted to have. She decided on 5′ 8″ and a size 7 shoe.

The sprinting legs she uses for competitive running and the everyday pair of VSP’s (Vertical Shock Prostheses), made in Southern California by a company called Flex-Foot, cost in the region of $7,000 to $12,000 each. “Male amputees love the VSPs,” she points out, “because they look so cool. They are great for playing tennis and other sports, but there are times when I just want to look like a woman.” Hence the pretty legs.

Because insurance companies cover only the most basic and functional of prosthetics, Aimee worked hard to find sponsorship from the prosthetic companies for her legs. “I had to become a businesswoman at a very young age,” she says, a determined cast to her jaw. That’s one of the reasons she’s so excited about her involvement in HOPE. “Unless you’re a sensation right away, it’s a long, hard struggle to get the funding for these things,” she says.

“I think that’s what I’m most proud of about her,” says Bernadette. “Just the fact that she’s independent and she’s doing for herself. She could be collecting disability, she doesn’t have to do all that she does. She could have a handicapped license plate on her car, but she doesn’t.”

Asked to describe herself in one word, Mullins chooses one which says a multitude: chameleon. “One of my dearest friends said that when she’s describing me to other people, the one word she uses is chameleon. She says: `You can put her in a pool hall or in an Armani gown and the girl is right at home.'” She laughs delightedly at the notion.

A couple of years ago, a friend of hers printed up some business cards for Aimee as a joke. She pauses as she tries to remember the list of rifles which appeared under her name on the card. “I think it was something like `Aimee Mullins — Olympic athlete, Supermodel, Oscar-winning actress, Nobel Peace Prize winner, Pulitzer Prize-winning author, Pilot, Secret agent, Master chef.'”

“And that,” she declares, “was before I had even done any of this stuff!” You get the impression she plans to do a lot more. She’s got the Olympics thing under her belt, and is well on her way to achieving her modeling goals, with a couple of jobs already lined up. At the time of going to press, Mullins was scheduled to work on a shoot in London with hot young British designer Alexander McQueen. As for the acting — her “first love” — she’s planning lessons with an acting coach. She’s also kicking around ideas for a book. “It won’t be a memoir,” she promises, “because I’m only 22.” Pilot? She flew helicopters in high school. Master chef might not be so far off the mark either, Aimee Mullins loves to cook (“and to eat,” she adds with a grin) and drops recipes into the conversation as casually as someone else might recommend a good book. She’s also fluent in Italian, paints (watercolors) and sculpts.

More immediately, Aimee is looking forward to heading back to Crusheen, Co. Clare to spend some time with her 86-year-old grandfather Thomas this summer. “I’m going back to Ireland for some healing,” she sighs. “Nobody cares what I do there – I’m just Aimee.”

Editor’s Note: This article was originally published in the July/August 1998 issue of Irish America. ⬥

Leave a Reply