Ice hockey is not traditionally regarded as a sport in which the Irish have had much input, but history records a large number of Malones, Clancys and Sullivans as having been hockey heroes. Today, their legend lives on through the likes of Brendan Shanahan and Colleen Coyne. John Kernaghan looks at past and present Irish ice personalities.

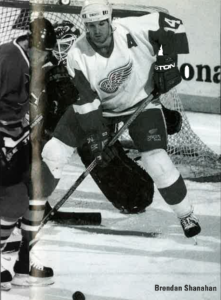

In repose, leaning on his hockey stick by the boards as he awaits the next drill, Brendan Shanahan is a knight in armor, the helmet cocked jauntily on an angle, the shoulder pads thrusting wide and the pants and shin pads thick and imposing.

But his new skates are pinching his feet. Abruptly, out of nowhere, Shanahan announces his retirement. It comes in mock headlines:

“SHANAHAN RETIRES. FEET ARE SORE.”

Gusts of laughter explode from his Detroit Red Wing teammates. The guy they call Shanny has developed a reputation as a major-league joker.

In fact, the high-scoring right winger of the defending National Hockey League champs is a throwback to hockey’s earliest days when the sons and grandsons of Irish immigrants were dominant in the world’s fastest game.

In an age where pro athletes carry their investment portfolios in Gucci valises, Shanahan lives for the game, the give and take of the dressing room, the tribal sense on the ice, where it’s my family against yours.

The NHL has always had a large population of Irish descendants, from early heroes like Joe Malone and King Clancy, through Red Sullivan and Red Kelly to the Mullen brothers, Joe and Brian, most recently and now Shanahan and Owen Nolan of the San Jose Sharks.

Irish names liberally dot NHL rosters. There are Shannons and Sweeneys, Fitzpatricks and Murphys, Sullivans and Patricks.

Moreover, a new tradition was born during the recent Winter Olympics when Colleen Coyne helped the U.S. women beat Canada for the women’s hockey gold medal.

But Shanahan carries the Irish standard highest right now, from the NHL title to several All-Star appearances to his role as the fateful fifth shooter in the tense Canada-Czech Republic shoot- out at the Olympics.

He plays hard, will fight and fight savagely if provoked and loves a laugh.

Throughout his career with four NHL teams, Shanahan has sprinkled funny falsehoods in his bio sheets, claiming at various times to have been a cattle rancher, pro soccer goalie, mountain climber, extra in the movie Forrest Gump and saxophone player.

Once in St. Louis a local TV station showed up in the Blues’ dressing room with a saxophone, asking him to play it. Shanahan sidestepped any problem with a glib, “Sorry, no sax on game days.”

He has a deep appreciation of his heritage, but even it is fodder for fun. “As much as we’re Irish,” he jokes, “we’ve inherited the fisticuffs and maybe not the singing.”

But ask Shanahan seriously about his roots and he talks about walking hand-in-hand with his son through a graveyard in Durrus, County Cork, the hometown of his late father Donal. How old is your son?

“I don’t have one.”

But his warrior/poet has `seen’ him, has imagined the day when he can retrace family footsteps with a son who is not yet born.

“It’s something I hope to be able to do some day, learn my roots so I’m able to pass them on.”

Last summer he visited the Bantry Bay area with his mother Rosaleen, and his fiancée. “It’s always special to go back there and see your roots and see where your parents were born and raised. We got to see the church where my father was baptized and two other small towns where he lived.”

Rosaleen was born in Belfast and his parents met in Canada and settled in west Toronto where they raised a small tribe of highspirited kids who became good athletes. A brother, Brian, plays professional lacrosse and a nephew is a budding junior hockey star.

When Shanahan was in the ninth grade, his father was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease. Describing a family trip to Ireland when Brendan was 16, he says: “That trip was the first time I kissed the Blarney Stone, and the last time my father did.”

Donal Shanahan died when his son was in his third season with the New Jersey Devils, but to this day, according to Sports Illustrated magazine, his son prays to his dad before his games: “During the [pre-game] national anthem, Shanahan crosses himself, recites an Our Father and follows with, `Dad, watch over me. Let me play my best. Take care of me.'”

Shanahan, who will challenge the 400-goal mark next season, was the Red Wings’ top scorer as they entered the playoffs this spring seeking to hold on to the Stanley Cup. This follows the bitter disappointment of the highly-favored Canadian Olympic team missing medals entirely. Shanahan had the last chance to keep his team’s gold medal hopes alive when they fell behind 1-0 in a shootout after 70 minutes of play couldn’t resolve who would go on to the gold medal game at Nagano.

But he was outguessed by all-world goalie Dominic Hasek and the Czechs went on to win the gold.

“Hero or goat, I’d stand up and want to take that shot again. But this is what losses do, make the victories that much sweeter.”

Would he play for Canada again?

“Yes, in a moment.”

Colleen Coyne’s Olympics was as dizzying as Shanahan’s was a downer. The 26-year-old native of Massachusetts proudly wore her gold medal in Boston’s huge St. Patrick’s Day parade. She won it in an emotional victory over the Canadian women.

Three generations of Coyne’s family grew up in largely Irish South Boston, so the parade and St. Patrick’s Day breakfast, which features politician-roasting, were a highlight for her. “It’s a huge deal in Boston and there were six members of the tern there. We got to share the stage with Vice President Gore. It was great.”

Coyne, whose grandmother’s maiden name was Lydon, grew up on Cape Cod and played hockey for the University of New Hampshire.

She says the Olympic experience has changed her life and also how women’s hockey is perceived.

“My schedule is very busy now making appearances and mothers are always coming up and saying how their little girls want to play hockey now. And I think the exposure we gave the game will start to put lots of people in seats at college games,” she says.

Coyne is not shy about advertising her heritage when she makes those appearances, noting that, “Just the whole idea of being Irish is great. My family is very proud of it. When I was growing up St. Patrick’s Day was my favorite day. We’d go visit family and friends in South Boston, see the parade.”

Owen Nolan, a star winger with the San Jose Sharks, was born in Belfast but came to settle in Welland, Ontario, near Buffalo, with parents Owen and Ellen and brothers Ryan and Gavin when he was an infant.

“The last time I was there was when I was five,” the bruising 6-foot, 3-inch broth said. “I talk with my relatives back there regularly and celebrate St. Patrick’s Day.”

But March 17th comes in the thick of the playoff hunt and athletes are a nomadic lot, so Nolan says he can’t give the holiday the attention it deserves.

“But I’m definitely planning to go back to visit my relatives one of these summers.”

Nolan is best known in NHL circles for a dramatic goal he scored in the West’s win in the 1997 NHL All-Star Game. He had already notched two goals and teammates were trying to set him up to complete the hat trick. But his shots kept getting turned aside until late in the game when he broke in alone.

Nolan audaciously pointed with his glove to the upper right corner of the net and then calmly rifled the puck to that spot.

The game was held in San Jose and drew a prolonged standing ovation as well as reruns in TV sports highlight packages.

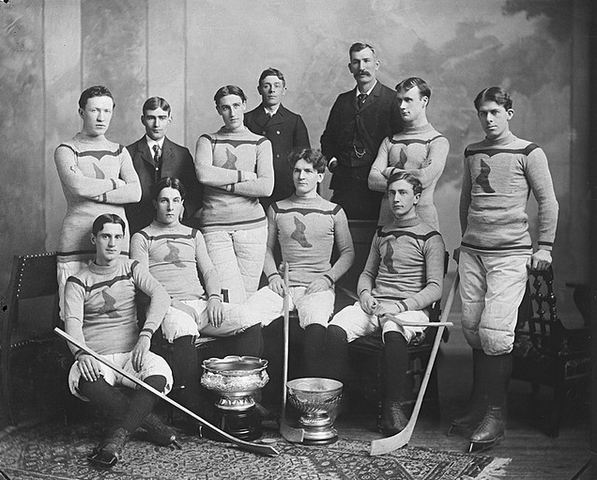

Irishmen were getting fans out of their seats from the very beginning of pro hockey. Joe Malone was top marksman in the NHL’s inaugural season, 1917-’18, with an incredible 44 goals in 20 games.

Teams of that period included the Shamrocks in Montreal, which eventually became the Canadians, and the St. Pat’s club in Toronto, forerunner of the Maple Leafs.

The Leafs were one of the first dynasties in hockey, mostly because of the drive of Conn Smythe, the son of an Irishman who built Maple Leaf Gardens during the Depression.

He also pulled off one of sports’ first huge free-agent signings when he ponied up $35,000, huge money in 1927, for Ottawa defenseman King Clancy.

But Smythe was $10,000 short as the transaction neared, so he acted boldly. Acting on a tip, he went to the Toronto racetrack and bet on a long shot.

It came in, Clancy emerged as one of the NHL’s early stars, and Maple Leaf Gardens has sold out almost continually since.

Even in a time of 5-foot, 9-inch, 160-pound players, Clancy was small at 5-7, 130 pounds. But he was absolutely fearless.

“I don’t think I ever won a fight,” the hall-of-famer said shortly before he passed away, “but I always showed up.”

The Patrick family are hockey builders with a long and proud lineage. First there was Lester, who played, coached and managed three championship teams with the New York Rangers in the 1920s, ’30s, and ’40s.

Then came his sons Muzz and Lynn, who both played for the Rangers and also were NHL general managers, and then Lynn’s son, Craig, who built two Stanley Cup champion teams as Pittsburgh’s general manager early this decade.

Lester is at the center of one of hockey’ s best vignettes. At age 44, while coaching the Rangers, his only goalie was knocked out of the game. There were no backups in those days so Patrick had no choice but to suit up himself, though he had never played goal.

He completed the game without giving up a goal and the Rangers won.

By the way, one of the key players in Craig’s championships team in Pittsburgh was Joey Mullen, the only U.S.-born player to score more than 500 goals in the NHL.

Joe and brother Brian first learned the game playing roller hockey on the streets of New York’s Bowery. Their father worked at the Rangers’ home, Madison Square Garden.

The Irish are well-represented in coaching ranks as well, with Mike Keenan guiding the Vancouver Canucks, Pat Burns behind the bench of the Boston Bruins and Mike Murphy coaching Toronto.

Keenan, of course, pushed the Rangers to their first Stanley Cup in over 50 years in 1995 and Burns has succeeded in the NHL’s toughest markets, Montreal, Toronto and Boston.

A towering figure in amateur hockey was John Francis (Bunny) Ahearne. The Co. Wexford native was president of the International Ice Hockey Federation for almost 20 years and is credited with strengthening it by negotiating valuable television contracts.

His most important contribution was bringing the U.S. and Canada back into the organization after both countries left in a dispute.

So will the Irish influence which permeates hockey today dissipate in time?

Though more and more Russians, Czechs and Swedes are advancing to the pro level, a look at the line-ups in American and Canadian junior and college ranks confirms there will be more O’Reillys and Kennedys, Noonans and Flatleys in the NHL and perhaps in a future women’s league.

With its dash and dating and great gushers of emotion, it appeals to Irish blood like no other North American sport.

Editor’s Note: This article was originally published in the May / June 1998 issue of Irish America. ⬥

Leave a Reply