HISTORIC NI AGREEMENT GIVES HOPE FOR FUTURE: Deaglán de Bréadún, Northern Editor of The Irish Times, describes an epic week in the history of the North of Ireland culminating in the historic peace deal.

℘℘℘

I have been privileged to cover two truly epic stories in my career as a journalist. One was the mass migration of the Kurds from northern Iraq into Iran and Turkey following their failed uprising against Saddam Hussein during the Gulf War.

The other was the conclusion of a peace agreement between the two warring traditions in the north of Ireland, at Castle Buildings, Stormont, on the outskirts of Belfast on Good Friday.

Two very different stories on the surface, but they had certain fundamentals in common. Both concerned a conflict between nationalities. There was great violence in both cases: short and vicious in the Kurdish situation; long-drawn-out but still vicious in the case of Northern Ireland.

We have not seen people starving to death on hillsides in Northern Ireland but we have seen soldiers kicked to death on television, innocent civilians shot down in the streets of Derry, dirty tricks by the state and shocking cruelty from guerrillas on both sides.

Psychologically, there has been a hopelessness and hate in the air in Northern Ireland for nearly three decades which the efforts of many good people has failed to dispel. British democracy has been to some extent poisoned by the expediencies of counter- insurgency. South of the Border, economic and social progress has been impeded by the overspill, both physical and psychological, from the northern conflict.

Huge efforts have been made down through the years to resolve the North’s age-old conflict. The Sunningdale power-sharing experiment of 1974 ended in failure. Violence continued and the deaths of republican prisoners on hunger-strike in 1981 paralyzed northern society for months.

Out of the hunger strikes came a renewed politicization of Sinn Fein, the political wing of the outlawed Irish Republican Army. The party’s electoral successes were accompanied by continuing IRA violence: the strategy of the ballot and the bullet.

It may have been the deaths of 11 innocent Protestant civilians in an IRA bomb attack at Enniskillen, Co. Fermanagh in 1987 that persuaded republican leaders it was time to start exploring an exclusively political approach.

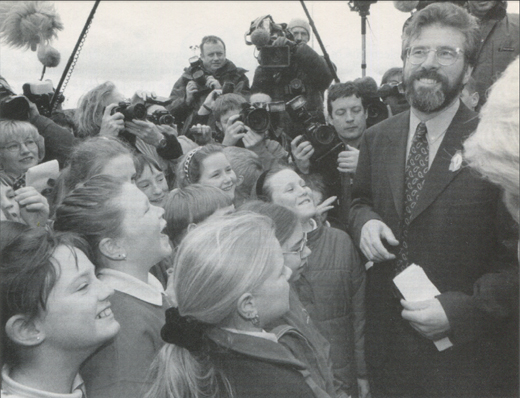

A dialogue began between the Sinn Fein leader, Gerry Adams, and John Hume, head of the moderate nationalist Social Democratic and Labour Party (SDLP). The Peace Process had begun. Others got involved, notably Albert Reynolds and John Major, heads of the Irish and British governments respectively.

The Downing Street Declaration emerged, with the British Government stating it had “no selfish strategic or economic interest in Northern Ireland”. The pace of events quickened: President Clinton incurred British wrath to grant a U.S. visa to Gerry Adams. Eventually the IRA declared a cease fire in August 1994.

Tragically, the British Government failed to grasp the opportunity then presented. The cease fire duly collapsed in February 1996 only to be re-instituted last July. The new Labour administration in London did not make the same mistake as its predecessor but instead cleared the way for Sinn Fein participation in multi-party talks on the future of Northern Ireland, including its relationship with the Republic and Britain: what had become known as “The Three Strands”.

There have been many ups and downs in the talks, which this reporter covered from Day One. Much of the time, agreement seemed almost hopeless, especially since the main pro-British party, the Ulster Unionists (UUP) refused to have direct face-to-face dialogue with Sinn Fein, now the third largest party in Northern Ireland.

Up to the last minute, the deal hung in the balance. The former US Senate majority leader, George Mitchell, had agreed to chair the talks and in the early hours of April 7th he produced the text of a draft settlement based on the discussions, which he presented to the parties.

Having rested-up after the long wait for Mitchell’s document, I arrived at the talks on Tuesday afternoon to discover the atmosphere had been electrified by the UUP’s rejection of the Mitchell document. A colleague sidled over to whisper the news that the British Prime Minister Tony Blair was flying in to perform emergency political surgery. But the tones of the UUP leader David Trimble’s rejection of the document did not seem to leave room for compromise.

From then on, reporters and TV crews could forget about a decent night’s sleep or even a short break from work as the talks went into overdrive. The Irish government leader Bertie Ahem arrived next morning but had to go back to Dublin to attend the funeral of his mother, Julia, who died the previous Monday.

The week must have been a colossal strain on Ahem, who flew back a few hours after burying his mother for a critical three- handed meeting with Blair and Trimble. Both Blair and Ahem are noted for their pragmatism and between them they gave Trimble sufficient reassurance to get him back on board. The final dealing had begun.

Extraordinary scenes followed. The Reverend Ian Paisley, leader of the Democratic Unionist Party and sworn opponent of talks with Sinn Fein arrived at Castle Buildings to make a protest. For years, Paisley has been the unchallenged political leader of the Protestant working-class in Northern Ireland. But in recent times the newly-politicized representatives of the loyalist paramilitary groups have been forging a political path of their own and television viewers witnessed the almost-unprecedented spectacle of Paisley being heckled by those who for years were among his most loyal supporters.

Something was stirring in the soul of the Protestant community. The talks went into their final, crucial phase on the morning of Thursday April 9th. A spokesman for Tony Blair kept stressing to reporters that midnight was a “fixed deadline” but this was just another attempt to maintain the psychological pressure on the parties and he admitted later that he hardly noticed it when midnight came and went.

The talks continued through Thursday night with many of us from the media staying up to await the outcome. Journalists who had been covering the northern conflict since it began in the late 1960s gathered together and there was almost a party atmosphere in the crude huts provided by the British Government for the media. A light fall of snow suggested Christmas but nobody was celebrating yet, we were still on white-knuckle time. Rumors and counter-rumors emanated from behind the closed doors where negotiations were taking place. There had been a retreat from some of the formulations in the Mitchell draft settlement and it looked for a while as if there were so many concessions to the UUP that Sinn Fein was no longer interested.

In the crisis atmosphere few of us could manage more than a short, fitful sleep. Eventually, Lord Alderdice, leader of the center-ground Alliance Party emerged to give a dawn press conference where he intimated in tones of some disbelief that the impossible was about to happen, the circle about to be squared and the parties on the brink of agreement.

But still the final denouement kept getting postponed. Copies of the Agreement had already been quietly slipped to favored journalists when it was reported that the UUP was having major internal difficulties.

A senior UUP member, Jeffrey Donaldson was said to be concerned at the possibility Sinn Fein members might be allowed to join a Northern Ireland government while the IRA was still in business. Crisis-time again: Blair enlisted the help of Bill Clinton to make reassuring noises over the phone.

Despite the misgivings of some of his own colleagues, Trimble decided to go for the deal. “I am doing it,” he was reported telling his party delegation, before walking out of the room.

I will never forget the sight of David Trimble that evening. He was like a man who could feel the electricity of history pulsing through his veins. A senior figure in the talks once criticized him for not realizing he was in a position to change the course of history and acting on that knowledge. But David Trimble’s moment had come and he was meeting the challenge.

After the deal was agreed, the two prime ministers gave a news conference to journalists who were for once almost stunned into silence by the scope of what was taking place. Trimble led his party out onto the steps of Castle Buildings and as he addressed the reporters a minor hailstorm began. It was a Shakespearean scene: the Hamlet of Ulster Unionism had made the quantum leap from possibility to action.

The document when it was released seemed to have something for everybody. The dogmatists on both the nationalist and unionist side were not long in denouncing it as a sellout of their respective traditions. Those of us not programmed for instant reaction were parsing and analyzing it to see who won and who lost. Was this a stepping-stone to a United Ireland, in Michael Collins’s famously tragic phrase, or did it represent a copper-fastening of partition, as republican diehards were claiming?

The multi-party agreement is long and complex: it provides for the establishment of a new Assembly in Belfast which, unlike the old Stormont parliament, will have built-in safeguards to ensure the nationalist minority cannot be overridden like in the bad old days.

There are north-south bodies where members of the Dublin and Belfast administrations will meet to discuss and agree common approaches on issues like tourism, transportation, aspects of agriculture, teacher qualifications, etc.

The areas for discussion are modest and it is a brave prophet who dares predict these north-south bodies will pave the way to a United Ireland. Nationalist supporters of the agreement say they are a step in the right direction and they will have scope to grow. Pro-agreement unionists say nothing can be done without their consent. Doubtless all will be revealed in time.

The north-south bodies were a gain for nationalists; in return unionists are getting changes in the Irish constitution. Dublin’s historic claim on the six northern counties is being watered-down: it will be subject to the consent of a majority in the Noah, which means it can’t happen unless a significant percentage of unionists agree.

There are other provisions: IRA and loyalist prisoners are to be released within two years (the Irish Government made the first move on this section with the early release of nine IRA prisoners from Portlaoise Prison in the Irish Republic on April 14); there will be a drive to ensure the equality of all citizens in the North, Protestant and Catholic; a commission is being set up to study reforms in the police force — the hottest potato of all.

In the immediate aftermath of the deal, Trimble won a majority of support from his party’s executive committee and from the Ulster Unionist Council, which accepted the Agreement by 540 votes to 210.

The Agreement is scheduled to go to referendum north and south of the Border on May 22nd. Should it be approved there, elections to the new Northern Ireland Assembly will be held on June 25th. Within a few months we could have a completely new political landscape in Ireland with wide ranging and, in some cases perhaps, unforeseen consequences. It looks as if the IRA and the mainstream loyalist guerrillas will remain on ceasefire but there are dissidents on both sides who are still on a war footing. We can expect more violence, probably many crises, and long nights for journalists before this story reaches its end. Resolving a marathon civil conflict was never going to be easy and we’re not out of the woods yet. ♦

℘℘℘

RESPONSE TO THE NORTHERN IRELAND AGREEMENT

“This is a day we should treasure, a day when agreement and accommodation have taken the place of difference and division. Today is the promise of a bright future, a day when we can hope a line can be drawn under the bloody conflict of the past.”

– Irish Taoiseach (Prime Minister) Bertie Ahern

“It means those who seek to kill and maim will be sidelined.”

– David Andrews, Irish Minister for Foreign Affairs

“I think that for all our people, Good Friday will be a very good Friday.”

– John Hume, SDLP leader

“Today the burden of history can at long last start to be lifted from our shoulders.”

– British Prime Minister Tony Blair

“After a 30-year winter of sectarian violence, Northern Ireland today has the promise of a springtime of peace.”

– President Bill Clinton

“I have that bittersweet feeling. I’m dying to leave but I hate to go.”

– Talks Chairman George Mitchell

“This historic breakthrough has once again demonstrated the value of negotiation and consultation rather than confrontation and upheaval.”

– Nelson Mandela

“I think it is absolutely historic. The people of Northern Ireland have to make up their own minds when they read and examine it.”

– David Ervine, Progressive Unionist Party

“Fly fishing.”

– Sinn Féin’s Martin McGuinness describes his dream job in the new Northern Ireland Assembly

“This agreement is good for all the people, North and South, and while many will try to defeat it, I believe it will pass. Ordinary people North and South will finally get a chance to prove that they want a just and lasting peace.”

– Talks Chairman George Mitchell

“It is my hope and prayer that this historic agreement will achieve the broad consensus essential for it to become the solid foundation for a new and lasting era of peace, justice and reconciliation in Northern Ireland.”

– Senator Edward Kennedy

Leave a Reply