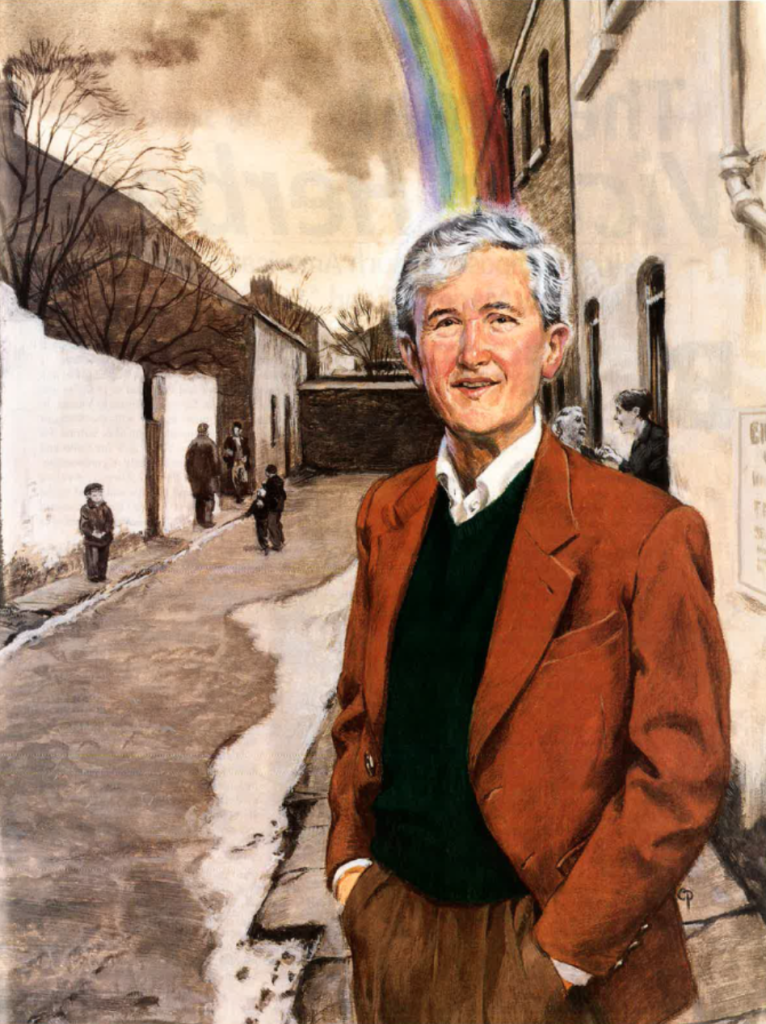

Malachy McCourt writes on his brother Frank

It’s the Irish thing again.

You’re not allowed to go careering around God’s globe boasting about your own or your family’s great accomplishments and doughty doings. In a dead moment in a pub or saloon, indulgence might be extended to a short bit on what the mother said, or the da did, or what the sister was a terror for, but that would be the extent of it. And, as noted all references must be in the definite article department, i.e. the mother. Saying “my mother” would elevate one to the level of the one being boasted about, and imply a certain responsibility for the achievements. However, the huge exception is always made for THE BROTHER (though the definite article still applies). Thanks to Myles na Gopeleen who legendized the brother with “D’ye know what the brother is after doing?” or “D’ye know

what the brother is after telling me?” all accompanied by a bemused smile, a shake of the head and the glint of the pride in the eye. Now there are three McCourts who can and do say, “D’ye know what the brother is after doing?” and of course we are referring to Frank, our oldest brother and patriarch. Heretofore, whenever we got together the conversation would have run along the lines of “Jesus, what is he thinking of?” As of course the absent one would be getting married again, going into business with crooks, getting stitched up from the last brawl, taking the pledge and so on. Lately it has been about sightings and news of the Pulitzer writer and stories about fending off first-time authors who would use us as conduits to the exalted one.

What about this man, the brother, Irish America’s “Irish American of the Year,” Frank McCourt?

He was never a big lad at any stage, an omnivorous reader but never bookish. He loved cowboy fillums and he knew (knows) every cowboy song ever sung by Roy Rogers, Gene Autry and the Sons of the Pioneers. Ask him to sing “Cool Water” to this day and you’ll get it along with “Twenty Miles to Nowhere,” “Down the Long Trail” and “There’s a Bridle Hanging on the Wall.” The lad’s imagination never stopped working, such as when he founded a soccer team with the strangely redundant name, “The Red Hearts,” and his efforts at fund-raising for the Foreign Missions, which consisted of putting several sheets of corrugated iron over some rocks which was to be

the stage for his adaptation of Hamlet in a Limerick lane. Kids paid a penny to come in and were promptly informed by Frank that they were now the horses in the cavalry and were to charge across the corrugated iron. The decibel level was so high from just walking on this crazy stage that no dialogue could be heard, which didn’t matter as the audience were now equines. Come the cavalry charge, the whole shagging thing collapsed and the monies had to be refunded to irate parents. Then there was the matter, yes, the matter of Frank’s chronically infected eyes. Every day of his young life began with him simply trying to open his eyes and see our world. Remedies were suggested by every know-it-all in the lane. Try the fasting spit, old tea leaves, vinegar, urine, poultices of bread and potatoes applied roasting hot, so that for years his eyes were angry looking and red-rimmed, bereft of a hint of an eyelash.

Oh yes, and they called him scabby eyes and Jap and Chink because he squinted in the light, but he was tough too with a temper to match.

There was the local bully, a swaggering fellow who had reached the venerable age of twelve and he tormented me, robbed me, hit me, teased me. I was about eight. When I complained I was told to stop whinging and fight him.

I didn’t have to. Frank went after him and demolished him and sent him home whim- pering to his mother.

It was taken for granted that Frankie McCourt was “brilliant” in school. That wan day he might get a job as a “clark” in an office where he would get to wear a collar and tie and never have to face the elements like the rest of the lane even if they were fortunate enough to get any kind of job, laborer or messenger boy.

Mr. Halloran the head master at Leamy’s National School said to Frank in my hearing, “You my boy are a literary genius, go to America for this is no place for you.” So when people say to me, “Isn’t it incredible what’s happened to your brother Frank?” I want to burst out and say, “No. God- damn it, it’s not incredible at all. I knew it, Mike knew it, Alfie knew it, and it was only a question of when.”

So that’s “The Brother,” as decent and compassionate and humorous a man as you’ll ever meet, who is nonjudgmental with unconditional love. A man who could never receive enough honors, prizes, plaudits and degrees to make up for the pain of the early years, but for now he says, “Thank you,” and I say, “My father thanks you, my mother thanks you, my brothers thank you, my sister thanks you and I thank you,” and that rumble you hear in the Irish sky is the God of the Lanes of Limerick enjoying a chuckle at the oddness of it all. ‘Tis, ’twas and ’twill be….

Editor’s Note: This article was originally published in the March / April 1998 issue of Irish America. ⬥

Leave a Reply