Neil Jordan’s newest film, The Butcher Boy, is perhaps the most stunningly original. Darkly hilarious, and set in what Jordan calls the “disappearing” world of isolated, rural Ireland, The Butcher Boy looks set to earn a place among the most important Irish films of all time. Brian Rohan spoke to Jordan, The Butcher Boy author, and Pat McCabe and County Cavan schoolboy Eamonn Owens, the 15-year-old who stole the show.

It’s hard to imagine who had the more difficult job: Patrick McCabe, author of the darkly funny coming-of-age novel The Butcher Boy, or Neil Jordan, who had to find a cast for the soon-to-be-released movie of the same name. McCabe likes to brag that his celebrated novel was first “rejected by every publisher in North America,” while Jordan argues that, in looking for a rough and tumble country youngster to play the lead character — 12-year-old Francie Brady — “we must have auditioned nearly every kid in Ireland.”

“You just couldn’t have made this without exactly the right kid to play Francie Brady,” says Jordan. “I’ve had the rights to The Butcher Boy since the book was published in 1992, but there was no way I would have even made the movie unless we found the right kid.”

While directing Michael Collins in 1995, Jordan dispatched two teams of casting scouts. The youngster had to be of the country sort, yet able to sport the cheeky exhibitionism of young Francie, a mentally disturbed character who enters adolescence without ever shedding the reckless energy and wonder of youth. After three sweeps of the country, more than 2,000 kids had read for the part, to no success.

“Country kids are shy,” explains Jordan. “We needed someone with Francie Brady’s optimism, someone who was young and unpolished, yet who could understand the brutality and humor of this boy’s life.”

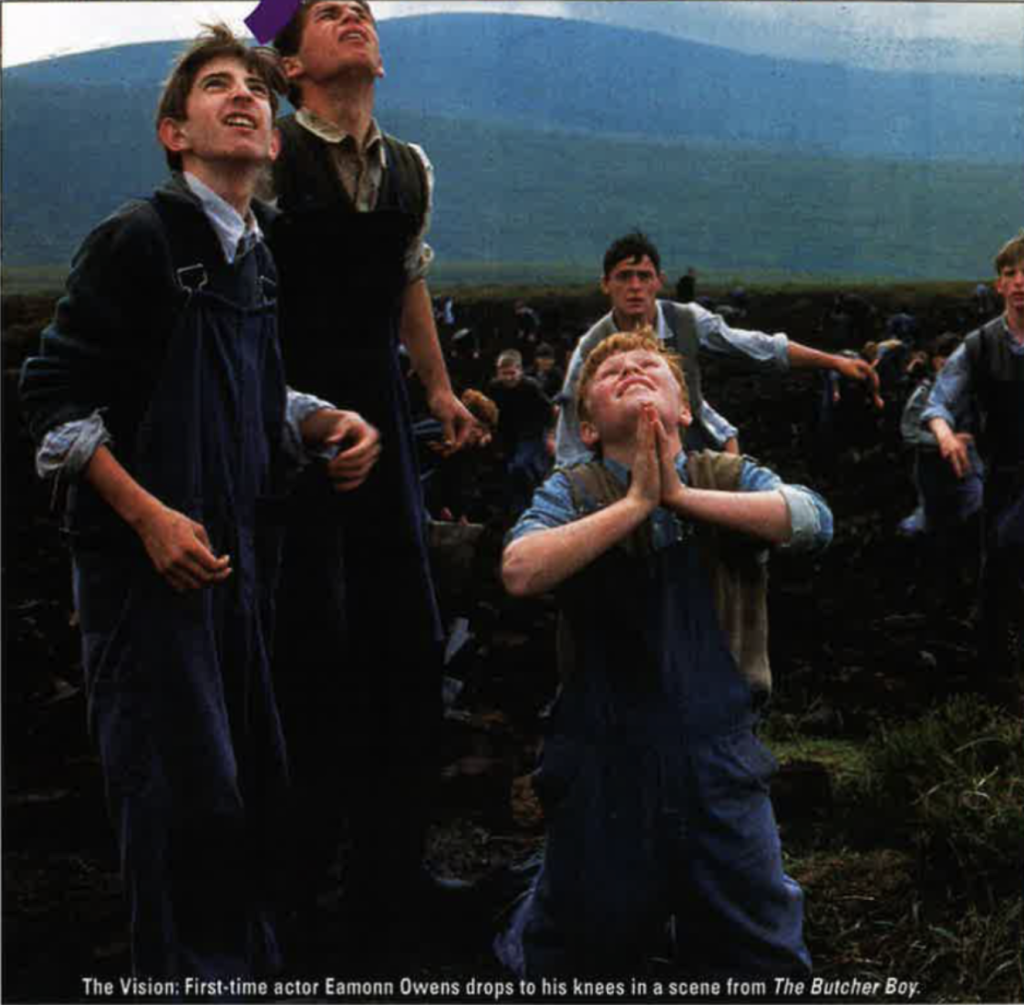

Enter Eamonn Owens, a 14-year-old shopkeeper’s son from Killeshandra. County Cavan, a 30-minute drive from Clones. County Monaghan where author Pat McCabe was born and where The Butcher Boy is set. Owens was not shy, and was not cloyingly `cute’ in the child-actor mold. Instead, he was rough-hewn and thick in the middle, a `townie’ in the rural borderlands who had never even been to a movie theater.

“Perfect,” said Jordan. “Eamonn understood the character. He was the one and only kid with the energy to play Francie Brady.” Pat McCabe agrees.

“Like a duck to water,” says the author. “Eamonn was so perfect that by rights, he never should have been found in the first place. He would turn in these amazing performances on the set and then run off to play football during the break. Then he’d come back and do it all over again. Perfect.”

Owens — who spoke to Irish America by telephone from his mother’s kitchen table in January, on the morning of his 15th birthday — said the making of The Butcher Boy was “no big deal,” just a bit of fun.

“Oh, I wouldn’t say that I’m a movie star,” said Owens. “My brothers have been slagging me by saying that, that I’m some big star, but I’m not. It was just me. It was just a movie.”

Despite Owens’ modesty. The Butcher Boy is more than just another Irish movie. As Irish America goes to press, many weeks before The Butcher Boy’s theatrical release in early April. critics it in Ireland and Britain are already buzzing about the film and especially the acting job done by Eamonn Owens. In the U.S.. predictions are that The Butcher Boy will be a likely contender for next year’s Academy Awards.

Such enthusiasm would seem to be fitting, considering the acclaim that greeted Pat McCabe’s novel upon publication six years ago. The New York Times praised the book mightily; overseas, it was short-listed for the prestigious Booker Prize. It has only grown in stature since, winning favorable comparisons to Huck Finn and Joyce’s Portrait of the Artist of a Young Man.

Yet The Butcher Boy was also a very unlikely book to be turned into a Hollywood movie. It is told in the first person, with a gown Francie Brady recalling from page one his misadventures: “When I was a young lad twenty or thirty or forty years ago I lived in a small town where they were all after me on account of what I done on Mrs Nugent….”

The difficulty was felt most acutely by Pat McCabe, who was asked by Jordan to create the screenplay adaptation.

“Instead of breaking down the material, I was writing new staff,” explains McCabe. “I’d submit a draft to Nell [Jordan] and he’d say, OK, it’s fine, but it’s not The Butcher Boy. I was writing things that didn’t even exist in the book, because it was very difficult for me to tell the same story all over again.”

The difficulty was compounded by the fact that McCabe had already re-written the novel once already as a stage play, Frank Pig Says Hello. which had been produced to critical acclaim in Ireland and New York. After “two or three” attempts at the screenplay. McCabe agreed to hand matters over to Jordan.

“Neil said, `Look, I didn’t ask you to write new material,'” recalled McCabe. “He’d say `Look, this is bull–, let me take care of it.’ And of course, Nell knows how to write a great screenplay, so I had no problem with that. I’m a bit more language-oriented and I don’t like the compromises on language you have to make in screenplay dialogue. When you write a novel, you’re in your own empire.”

Jordan had the structure, but realized McCabe’s ear for dialogue was essential. The result was a screenplay very faithful to the book, with a day-glo feel in time with Francie Brady’s fascination with comic book culture.

“It was important to make sure this was not another depressing Irish film,” said Jordan. “I wanted it to be like a big comic book, full of color and vitality and optimism.”

Much of the story is set in 1962 Ireland, and from the viewpoint of Clones, the world is coming to a mushroom-clouded end in a matter of days, thanks to the Cuban Missile Crisis. While the rest of the town prays Novenas and roots for the upright and handsome President Kennedy, young Francie gobbles up the exploits of The One-Armed Man (whom he calls “the hoppity bastard”), and watches The Lone Ranger through the lace-curtained window of his neighbor and chief nemesis, Mrs. Nugent.

“Pat McCabe’s perspective on the Cold War era is very much the way I remember it as a kid myself,” said Jordan. “There was this surreal drama going on thousands of miles away, and to us there was this young, good-looking guy who was also Irish and Catholic and the American President, and then there was Krushchev and the Russians — they were the bad boys, the football team from the next town over. There was this attitude of, `We’ll go down there and give them lot a right thumpin’ and sort `em out, the bastards.’ Francie Brady sees it very much in this way, like it’s all a big comic book.”

One of the movie’s most inventive scenes has Francie and his best friend Joe wandering through a post-apocalyptic dreamscape, the only survivors of a nuclear war that somehow began and ended in Clones. Francie and Joe are shown romping through the wreckage of the town abattoir, where Francie had worked as a butcher’s apprentice. The ruin is just a big laugh to Francie, who chats up the scorched carcass of a massive hog, hanged by its ankles from the slaughterhouse ceiling — “Who’s a pig now, eh?”

“Neil directed it beautifully,” says McCabe. “Parts of the film look like one of those John Hinde postcards of donkeys and red-haired girls you’d get in Ireland, with these impossibly bright greens and reds. The effect is that it subverts that Irish dark movie thing. It takes that Irish dark movie cliché and blows it apart.”

In keeping with the surreal feel, Sinéad O’Connor was cast in a small but vital role, that of young Francie’s idealized vision of the Virgin Mary. Learning of the Virgin’s apparition to children across Europe and of the phenomenon of “moving statues” in Ireland, young Francie — at the time stabled at a boys’ reformatory run by the Irish Christian Brothers — decides the only way to “get better” is to witness a few apparitions himself. O’Connor, wearing the Virgin’s traditional blue robes, dispenses advice in the voice of Francie’s own dead mother.

“I had seen Sinéad years ago in Hush-a-Bye-Baby [an independently-made Irish movie] and she was fantastic.” said Jordan. “She has those strong, stem features I remembered from the religious statues when I was a kid. She appears to Francie as a very understanding, calming voice, at a time of turmoil.”

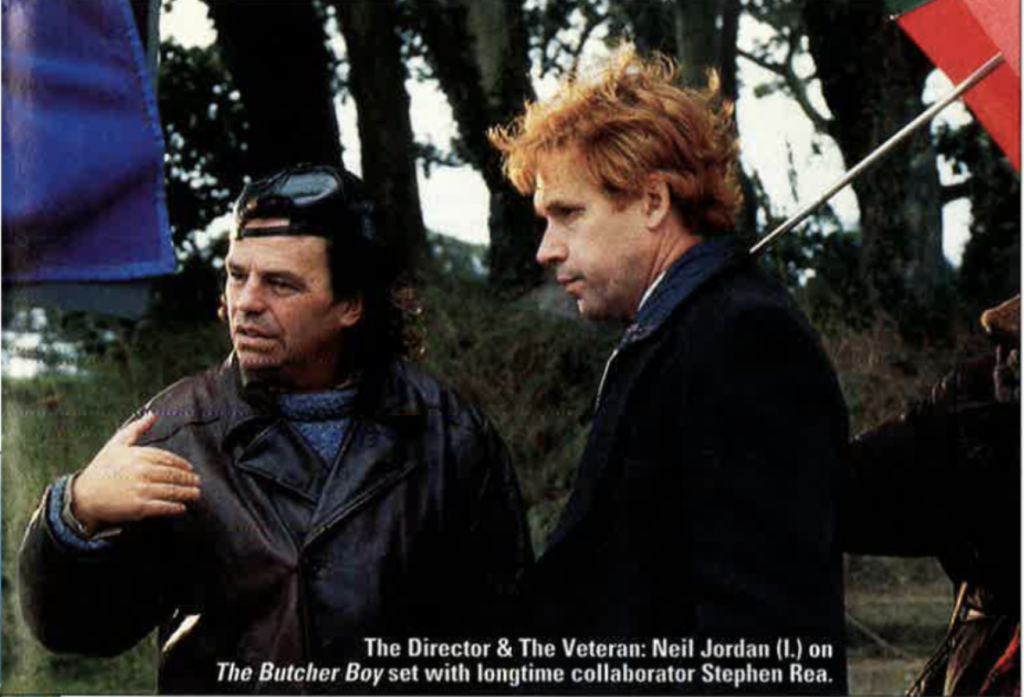

Anchoring the film is longtime Jordan collaborator Stephen Rea, who serves double-duty as young Francie’s widowed, alcoholic father and also the grown-up voice of Francie the narrator. The Belfast actor tums in one of the performances of his career by delivering the voice-over in the quick, densely-packed dialect of the Cavan and Monaghan border areas. Jordan and McCabe agreed to retain the specific affectation of the border accent rather than adopt a more generic Irish brogue.

“We reckoned if Martin Scorsese and Joe Pesci can rap along at 96 miles an hour with no concessions to our ear, then why shouldn’t we do it’?” says McCabe. “It’s essential to the rhythm of the dialogue, the rhythm of the book, the rhythm of the movie. We had to give the movie the texture it deserves.”

Filmed last summer in Clones. The Butcher Boy cast “just about everyone” in McCabe’s hometown, including McCabe himself, who has a tiny role as a friendly village drunkard.

“Neil reckoned I was probably the best drunk in town.,” jokes McCabe. “But that little bit of acting was probably one of the most difficult things I’ve ever done. It’s amazing how hard it is just walking and talking at the same time, remembering your lines. I give readings all the time but that’s just your voice and your hands. It’s amazing to all of a sudden realize you’ve got a pair of legs too and now what do you do with them?”

McCabe and Jordan had an unusually close director-author relationship, with McCabe renting a house in the center of town for the duration of the shoot. McCabe says there was no problem between the two auteurs because he completely trusted Jordan’s vision of how the story needed to be told.

“He knew, he knew what to do with it,” says McCabe. “The only thing I made clear was I didn’t want some kind of crass social research case. Some people say it’s the story of a young boy driven mad by these hypocrites in a small town but it’s much more than that. I knew Neil would bring a bigger perspective so you would have a very magical, dreamlike movie rather than one that’s earthbound.”

The only trouble McCabe got into was from his two pre-teen daughters, who he says were angry they didn’t get bigger parts.

“Oh they were furious,” he laughs. “They’re in it for a fraction of a second and they just wondered why daddy couldn’t have gotten them a bigger part. Thank Christ my wife didn’t want to be in it at all, said she was too shy, or else I’d be in even bigger trouble.”

AS for Eamonn Owens, the 15-year-old shopkeeper’s son has a fast-growing reputation as something of a prodigy. After 10 weeks of filming The Butcher Boy last summer, Owens was signed to act in the Irish television production of John McGahern’s Amongst Women. He was also snapped up by Excalibur director John Boorman to star in The General, playing real-life Dublin crime figure Martin Cahill as a youngster. Owens says that the comic-book obsessed, Cold War-era character of Francie is not that far removed from his own classmates.

“Francie’s a great character, I had great fun doing him, because he was a real kid,” said Owens. “The things that went through Francie’s head would go through a kid’s head. You mightn’t go and act on them and do the things that Francie done, the bad things, but they’d be in your head.”

Will Owens, the second-youngest in a family of six, stick with the acting?

“I dunno,” he says, “Depends how The Butcher Boy goes. I loved it, so if they ask me to be in something else, l’d do it.”

For now, Owens is still in school, is an avid supporter of the Cavan Gaelic football team and plays soccer and hurling. As The Butcher Boy’s theatrical release draws nearer, Owens says he has his hands full fighting off the teasing of his four brothers and his classmates.

“There was a bit of the film on the TV here and ever since then my friends haven’t stopped, all the time saying “Oh hel-lo Miss-us Canning!” like I did in the TV commercial,” says Owens. “Wait fill they see the part with me wearing a bonnet!”

Of course, with the bad comes the good, like the computer and video games Owens bought with his Butcher Boy paycheck. Will he be bringing his brothers and friends to the movie’s opening?

“Well there’s no cinema here in Killeshandra, so we might have to drive down to Monaghan town,” said Owens. “Or maybe the movie people will fly us out to America. Now wouldn’t that be grand?”

Editor’s Note: This article was originally published in the March / April 1998 issue of Irish America. ⬥

Leave a Reply