At first glance, the Irish Brigade in Elko seemed a bit out of place amid the sea of ten-gallon hats, blue jeans, and high-heeled cowboy boots. Elko, after all, is the home of the Cowboy Poetry Gathering, the premier celebration of the folk traditions of the American West. So this Nevada gold-mining, high desert town is used to playing host to buckaroo bards, rappin’ ropers, and connoisseurs of cowboy culture. But what were these Irish guys in tweed caps doing here in the land of the Stetson?

“We’ve been very interested in the roots of what became cowboy poetry and cowboy ballad,” explains musician and folklorist Hal Cannon, founding director of the Western Folklife Center. So this January, a Celtic contingent from Ireland and Wales brought their own stories, recitations, songs, and fiddle tunes to the 14th annual Cowboy Poetry Gathering Nevada Roundup.

The Irish visitors may have been brought to Elko to represent old-country roots, but they weren’t completely out of place in a cow town. “I farm ten cows,” declared Patrick Lynch, the recitation specialist from Mullagh, County Clare. “But I don’t know if that would be considered ‘raising’ cattle — they would be kind of dragged up.” His farm, he says, would fit on the ground floor of Elko’s Stockmen’s Hotel & Casino.

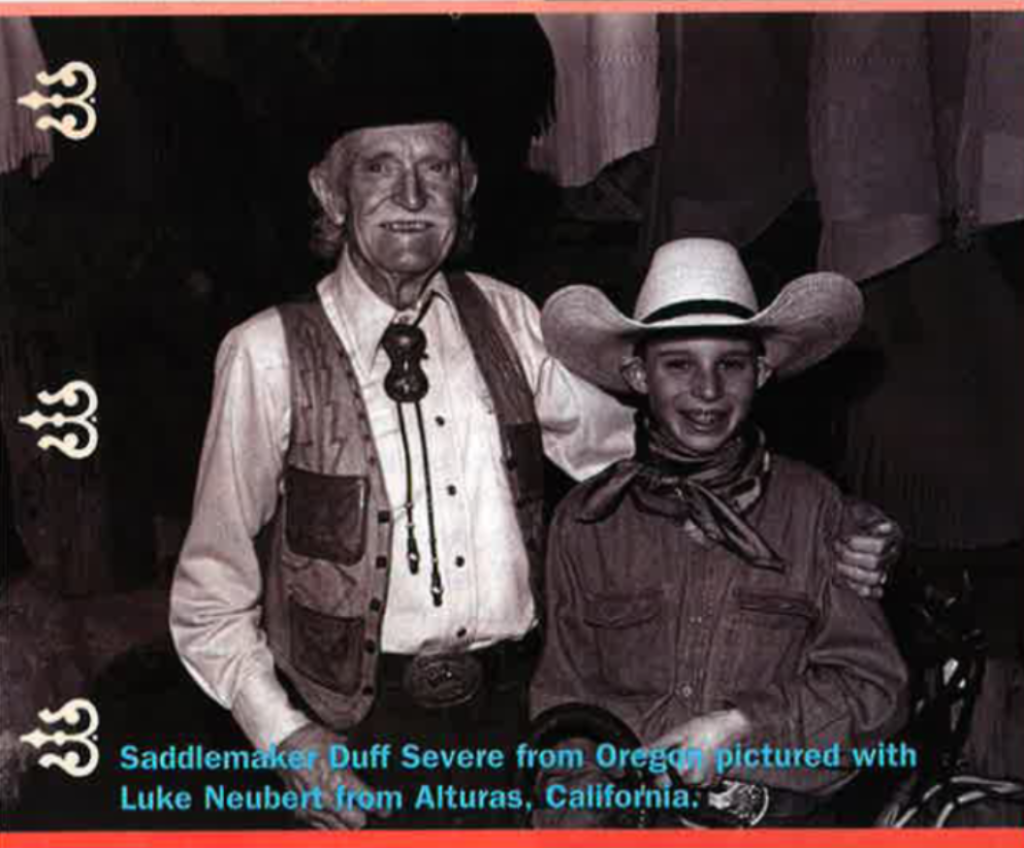

Eighty-something Michael McDermot, another Irish reciter, keeps a few head of cattle on his hillside farm about the town of Letterkenny. Michael had never before been so far from home as Donegal town, but once in Elko he quickly turned cowboy, exchanging his flat-crowned Donegal tweed cap for a wide-brimmed western model

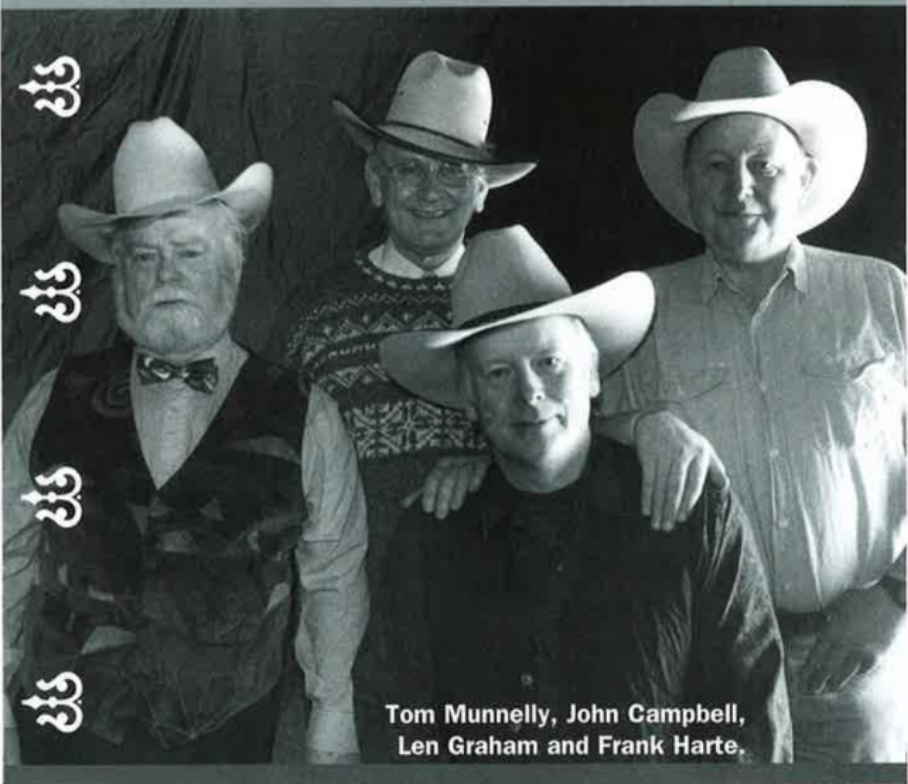

Most of the other Irish visitors had rural roots as well. Fiddler Martin Hayes is something of an international celebrity these days, but he grew up in farm country near the town of Feakle in east County Clare. Storyteller John Campbell and traditional singer Len Graham came down from the hills of Mullaghbawn in south Armagh. Dubliner Frank Harte was the only city boy, but the folks in Elko were willing to overlook that as Frank is one of Ireland’s most renowned traditional singers, a man who knows some 800 Irish ballads by heart.

Frank was delighted at the reception given to the Irish performers in Elko. “Here people are interested in listening to stories and songs.” In Ireland, he complained, the main emphasis among traditional music fans is on instrumental tunes. “And when you finish your one song, they all go, `whew,’ and get back to playing music again.”

A Cowboy Fleadh

The first Cowboy Poetry Gathering in 1985 attracted only a few hundred people. It has since grown into an enormously successful week-long celebration that draws some 8,000 visitors from all over the West, with some die-hard fans coming from as far away as Australia. What they find in Elko is an extensive cultural smorgasbord that includes classes in horsemanship, exhibits of cowboy arts and crafts, concerts, dances, poetry readings and seminars on topics like “Dynamics of Inter-Generational Ranching.” There are usually at least four or five events on at any one time during the week. Some of the most popular, including performances by Texas singer Don Edwards and humorist Baxter Black (“the Robin Williams of cowboy poetry”), sell out long in advance.

The late Buck Ramsey, a much-loved Texas cowboy poet who passed away just before this year’s gathering, explained the appeal of the event to the Elko Free Press: “The cowboy story is the one mythology America has given the world. Not the kind that’s filled with B.S. from Hollywood, Nashville and New York, but the real thing. America’s hero is finally getting to speak in his own voice.”

This year the Irish contingent gave lilt to that voice and added to the craic.

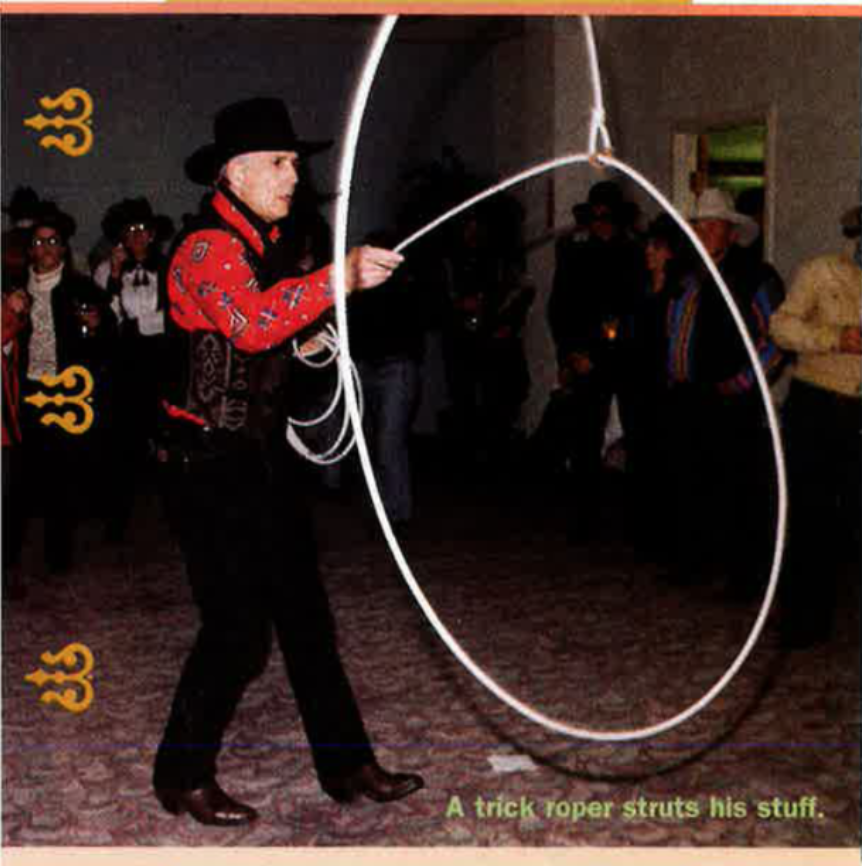

After the official events finished each evening, performers and fans rendezvoused at the Stockmen’s Casino, where the bar never closes. By Saturday night, the scene upstairs at the Stockmen’s was a cross between an All-Ireland Fleadh Cheoil (music festival) and a three-ring circus. Poets, fiddlers, trick ropers, guitarists, and singers partied till dawn. A band of Indians played cowboy songs. On the other side of a partition, a bluegrass group was picking and grinning while a Scottish fiddler jammed with an American playing a musical saw.

From Armagh to Laredo

The cowboy songs as celebrated at the Elko gathering don’t much sound like commercial “country” music, nor do they have a lot in common with the modern singer/songwriter genre, which Texan Don Edwards described as “woe-is-me songs of dysfunctional urban captivity.” Like cowboy poetry, the songs are down-to-earth ditties about ranching and riding. In Elko, moreover, the singers and poets are not rhinestone wannabe’s but genuine cowpokes.

Hollywood and Tin Pan Alley occasionally tried to fuse cowboy and Irish clichés. Bing Crosby, for example, once crooned a song about “Two-Shillelagh O’Sullivan”:

There’s many a man who rode a horse across the Western plains

There’s never been one like the Irishman, O’Sullivan was the name

He never carried a shooting iron, the need he never felt

But two shillelaghs at his side, hanging from his belt

At throwing a rope or branding calves he was a mighty man

At handling his two shillelaghs,the fastest in the land.” “Two-Shillelagh O’Sullivan” notwith-standing, there are many genuine connections between American and Irish folk music. Frank Harte travels each year to teach at a music camp in West Virginia, where he swaps songs with Appalachian musician Jerry Mills. “Jerry has a rake of songs,” Frank told the audience at an Elko ballad workshop, “and nearly any song I’d sing, Jerry would come back with a version of it from the Appalachians.”

Those Irish songs traveled west with the pioneers. Versions of the classic County Sligo ballad “Willie Reilly and the Colleen Bawn” have turned up in Texas. “The Wild Colonial Boy” was sung in Butte as “The Wild Montana Boy.” Even “The Streets of Laredo,” perhaps the most famous western song of all, is just a Texas cowboy version of an old Irish ballad. At one evening concert in Elko, western singing star Michael Martin Murphey underlined the connection when he joined David Wilkie and Cowboy Celtic to perform the song’s Irish ancestor, “Phelim Brady, the Bard of Armagh.” Cowboy Celtic, a group based in Alberta, Canada, also made another Celtic connection clear by performing the Irish song “Níl Sé na Lá” (It’s not the Day) together with “Spanish is the Loving Tongue,” a Western standard that shares the same melody as the Gaelic original.

The Bunkhouse Orchestra was another group in Elko whose music recalled that of the Emerald Isle. Bunkhouse fiddler Ron Kane, who traces his ancestry back to Newmarket-on-Fergus in County Clare, says he took up his instrument after a trip to Ireland: “I was force-fed violin lessons when I was a child and didn’t enjoy the classical approach to music, so I quit as quickly as I could. Many years later, in 1968, I took a trip to Ireland, the first of three. I was in Tipperary and went to look for a fishing hole in the Glen of Aherlow. I went into a pub and the lady that was tending bar pointed me into a room where there were lots of singers and musicians. I enjoyed myself so much that I was inspired to try my hand at it.”

Kane has cultivated a purely American fiddle style, but many of his tunes could easily accompany a Kerry polka or an Irish old-time waltz. His Bunkhouse partner Meghan Merker also added to the Celtic flavor with “My Dearest Dear,” an American song with Irish roots, and some flat-foot “buck dancing” clearly related to old-time Irish step dancing.

“Strange Things Done in the Midnight Sun”

The poetry boom set off by the annual Elko gathering has added a great deal of new material to the stock of Western folk verse created by late 19th-century bunkhouse versifiers, many of whom were inspired by the works of Rudyard Kipling and Robert W. Service. Among the best of the Elko poets are Colorado rancher Vess Quinlan, who cultivated his thoughtful modern style at university poetry classes, and Canadian cattleman Frank Gleeson, who delivered humorous verses with the speed of a galloping bronco.

Despite this modem influence, old standards such as Service’s “The Shooting of Dan McGrew” and “The Cremation of Sam McGee” remain cowboy favorites. Both poems have long been popular in rural Ireland. Donegal man Michael McDermot joined Montana rancher Wallace McRae and Texan Buster McLaury on stage and delighted the Elko audience with his Ulster-accented rendition of “Sam McGee” (“There are strange things done in the midnight sun by the men who moil for gold…”). Then he followed it up with “Mark and Moll’s Wedding,” a hilarious rhymed account of the nuptials of an Irish amadán and his equally foolish bride.

The popularity of spoken verse in Ireland traces its roots to the ceili, or house-visiting, tradition is still evident in some rural areas. It was required that everyone have a “party piece” to perform, singer Len Graham explained; “if somebody couldn’t sing or play an instrument, they would learn a recitation.” Storyteller John Campbell described the scene at one old-time Armagh ceili:

“There was an old woman used to come into our house, and she’d been a good singer in her day. But when the voice started to cracken a bit, she wouldn’t sing. And there was Scotch visitors home in our house and me mother said, respect for the recitation, because it was another story. And that’s really all the ballads are, an extension of the story.”

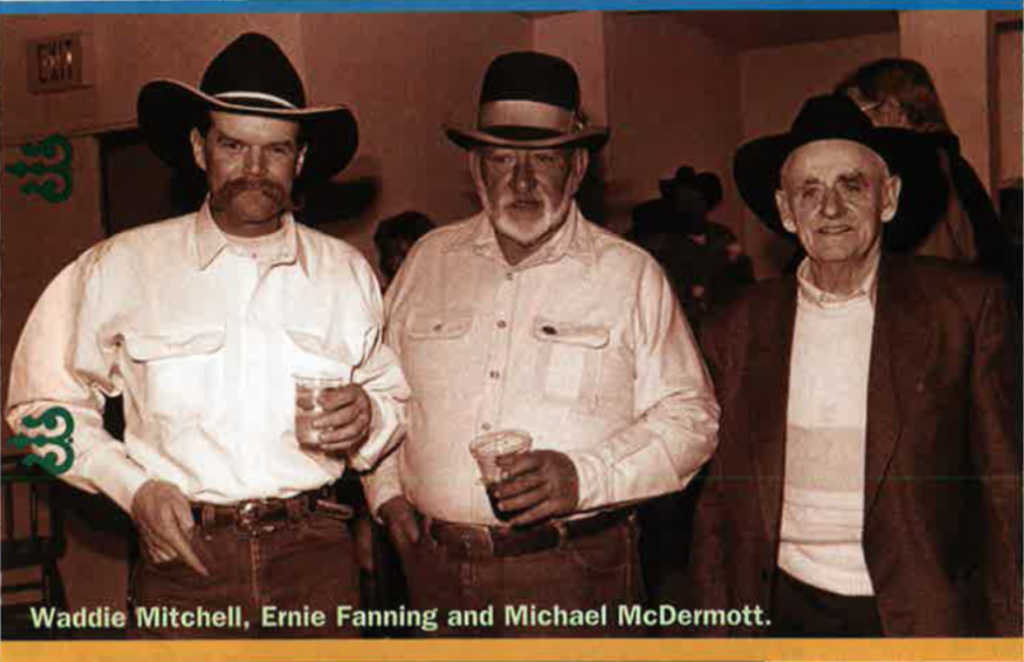

John Campbell and Elko’s own Waddie Mitchell demonstrated that some rural humor is the common property of Nevada cowboys and Irish farmers. With deadpan delivery and exquisite comic timing, Campbell told a story about a horse with an eye problem that was cured by a vet who blew on a hose stuck in what a cowboy might call the animal’s “south end.” The next day, Mitchell, whose handlebar mustache is as broad as the brim of his Stetson, recited a cowboy poem about the same unlikely cure, with an identical punch line.

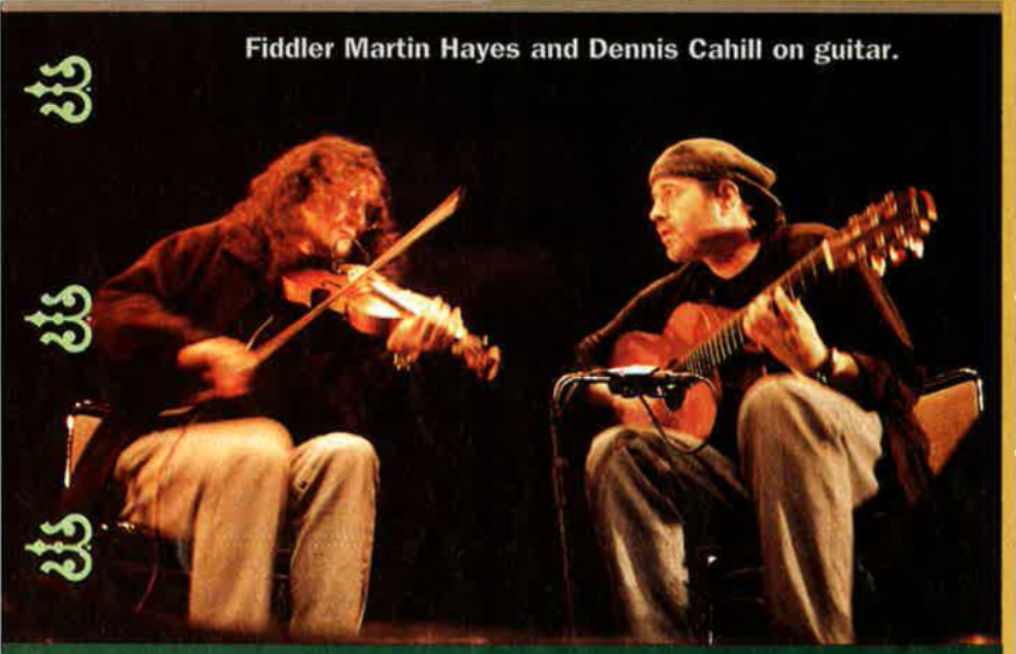

The 1998 Cowboy Poetry Gathering culminated with two sold-out Saturday night concerts in the 900-seat Elko Convention Center auditorium. Storyteller Daniel Morden spun tales from Welsh mythology. Clareman Patrick Lynch declaimed recitations both funny and sad while John Campbell had the crowd in stitches with humorous stories from the hills of south Armagh. Martin Hayes and Dennis Cahill won a standing ovation with some breathtakingly brilliant fiddling and guitar playing. Finally, as the house lights came on, it was left to singers Len Graham, John Campbell and Frank Harte to bid an Irish farewell to Elko in the chorus of an old Ulster song:

“Here’s a health to the company, aye and one to my lass

Let’s drink and be merry all out of one glass

We will drink and be merry, good drinks and refrain

That we may and might never all meet here again.”

Editor’s Note: This article was originally published in the March / April 1998 issue of Irish America. ⬥

Leave a Reply