Irish settlers and their contribution in the formation and development of the Lone Star State.

Irish immigration to Texas is so old that it has its roots in the Iberian Peninsula and the marriage of Isabella I of Castile to Ferdinand II of Aragon. The union of the two Spanish Provinces, and the subsequent expulsion of the Moors after the Battle of Granada, paved the way for the colonization of America. Spain’s first incursion into Mexico, which then included Texas, occurred in 1519. By the end of 1521, they had effectively subdued the Aztec Empire and limited New World immigration to residents of Castile. That privilege was later extended to the Irish, a fact which no doubt accounts for the various Irish names found throughout Latin America. Some of these early Irish served as soldiers in the Spanish Army. Others were involved in the building and administering of the Missions. The cornerstone of the San Jose Mission about five miles from downtown San Antonio was laid by Hugh O’Connor in 1752.

Despite the haphazard nature of Irish immigration to Mexico during the colonial period, a sizable number of them were present in that country when it seceded from Spain in 1821. On August 18, 1824, the Supreme Government of Mexico adopted a general colonization law. In that same year, its two provinces of Texas and Coahuila united to form the State of Coahuila and Texas. On March 24, 1825, Coahuila and Texas promulgated its own colonization law subservient to the national law. This would lead to the formation of two contiguous Irish colonies, Refugio and San Patricio de Hibernia, near the modern day Texas city of Corpus Christi. In opting to emigrate to Texas, the Irish colonists became enmeshed in disasters and difficulties heretofore unimaginable. Many would succumb to cholera while others lost their lives at the hands of marauding Indians. Others would be massacred during the Texas War for Independence and a few lucky ones would become millionaires.

As defined by the general Mexican colonization law, a family received one labor (177.1 acres) if they used the land exclusively for cultivation. If they engaged in the raising of livestock as well as cultivation, an additional sitio (4428.4 acres) was added on. Should they decide to raise livestock exclusively, they received 1 sitio minus 1 labor (4251.3 acres). A single man received only one quarter the amount of a family. However, on marrying, his demesne was increased to equal that of a family. If he married a Mexican woman, his holding was augmented by an additional quarter of the total. The Empresarios or land agents respon- sible for bringing over the colonists got five sitios plus five labors (23,027.5 acres), for each 100 families they introduced to the colony from Ireland.

As residents of the colony, they also received additional allotments commensurate with that of any regular settler. When a new town was laid out within each colony, each settler was given a square block to build a home while the Empresarios were given two.

The Refugio Colony stretched from the Nueces River which flows into Nueces Bay-the eastern section of Corpus Christi Bay–as far north as the Guadalupe River which empties into San Antonio Bay. It stretched westward along both rivers a distance of ten leagues. The western boundary was a straight line running north-south connecting the two westerly points on the rivers. However, this border was ill-defined and would cause problems later on with the other Irish colony. The offshore islands of Matagorda and Saint Joseph were added on December 30, 1834, but the Empresarios never got an official title to all of these islands.

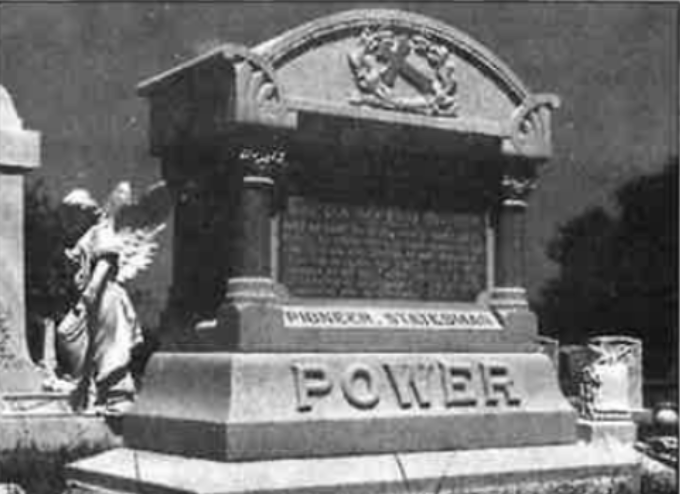

James Power from Ballygarret, County Wexford, and James Hewetson from Thomastown, County Kilkenny, were the founders of the Refugio Colony, so named because its center was located at the old abandoned Spanish mission of Refugio which was established at its third location on the Mission River in 1795. Power emigrated to the United States as a young man and spent twelve years in New Orleans before relocating to Saltillo, Mexico, where he became well established as a merchandiser and drilling equipment expert.

He married Delores Portilla who belonged to a well established Spanish-Mexican family. Power would later become a prominent military and political figure in Texas during the revolution against Mexico as well as a close confidant of Sam Houston, the future President of Texas.

Hewetson, who studied medicine in Ireland, also emigrated to the United States as a young man and settled in St. Louis, Missouri. He was the doctor for the entourage of Stephen F. Austin when the latter went on an expedition to San Antonio, Texas to accept title to lands granted to his father, Moses Austin, by the Spanish authorities. Hewetson parted company with Austin in San Antonio, just after secession from Spain, and domiciled himself in the City of Monclova. His business interests took him on frequent journeys between

that city and Saltillo where he met Power. Hewetson would eventually marry a wealthy Mexican widow, Josefa Guajardo, whose land holdings were so vast that he was forced to extricate himself from the administering of the Refugio colony shortly after its inception. As developments will indicate, Power and Hewetson were well connected with ranking officials in Mexico, a fact which no doubt ameliorated their plight when a myriad of precarious situations and legal ramifications crossed their paths further down the road. They filed their first petition to form a colony with the State of Coahuila and Texas on September 29, 1826. Their aim was to control the coast of Texas from Galveston Bay to Matomoros, the present day border with the United States. Since littoral areas were involved, the Supreme Government only of Mexico had to validate the application. On April 22, 1828, the Supreme Government gave its permission, subject to state ratification, for Power and Hewetson to colonize an area from the Nueces River to the La Vaca Creek north of the Guadalupe River. However, on June 11, 1828, the State of Coahuila and Texas ratified the agreement only for the vacant lands lying between the Guadalupe River and the La Vaca Creek.

Undaunted, the two Empresarios filed another petition with the State and on April 12, 1829, the then State Governor, Jose Maria Viesca, granted them permission to colonize the vacant lands from the Nueces River at the present day city of Corpus Christi as far north as the La Vaca Creek. Eventually, they would have to give up the area between the Guadalupe River and the La Vaca Creek after becoming enmeshed in litigation with the neighboring DeLeon colony. The contract stipulated that they settle at least two hundred families from Ireland as well as two hundred Mexican families. Power and Hewetson agreed to this.

A myriad of complaints to the government subsequent to the granting of colonization rights to the two Irishmen ensued. Many of these came from the old established Spanish settlement of Goliad which actually lay outside the boundaries of the Power- Hewetson territory, but whose citizens claimed prior title to part of the lands. Additionally, the abandoned Refugio Mission and its huge tract of lands situated in the middle of the colony had not yet officially reverted to the State. Adding insult to injury, two other Irish Empresarios, John McMullen and James McGloin, would attempt to usurp their colony.

McMullen’s birthplace in Ireland is unknown. It is believed that he resided in Baltimore, Maryland after emigrating to the U.S., before moving to Matamoros, Mexico. Like Power, McMullen would also become a powerful political figure in Texan politics. McMullen County, Texas, bears his name. McGloin, who was a native of Leitrim, met McMullen at the docks in Liverpool after missing his ship to Australia. He decided to accompany McMullen to the U.S. and later became a partner in his merchandising business in Matamoros.

On August 16, 1828, McMullen and McGloin were granted a contract for a colony on the Nueces River. It began ten leagues up the Nueces River at the point where the Power-Hewetson colony ended. Its southern border followed the right bank of that river for a distance of about fifty miles. It stretched northwards to about the middle of the Power- Hewetson colony and then followed a straight line northwestward to the confluence of the Medina and San On August 16, 1828, McMullen and McGloin were granted a contract for a colony on the Nueces River. It began ten leagues up the Nueces River at the point where the Power-Hewetson colony ended. Its southern border followed the right bank of that river for a distance of about fifty miles. It stretched northwards to about the middle of the Power- Hewetson colony and then followed a straight line northwestward to the confluence of the Medina and San Antonio Rivers. Its western border was supposed to be a straight line joining the latter points on both rivers but was not well defined. It was much larger in area than the Power-Hewetson colony. Since no coastal lands were included in their territory, they ran into few legal difficulties other than those created by themselves. McMullen and McGloin attempted to get most of their Irish colonists from U.S. cities on the East Coast, particularly New York.

They chartered vessels to take these colonists to Texas. In 1829, two vessels- the Albion and the New Packet- sailed from New York laden with Irish-born colonists. The New Packet colonists arrived at Port Aransas on Mustang Island off the Texas coast and were ferried across Aransas Bay to Copano Bay on the mainland and within the confines of the Power-Hewetson colony, where they stayed for some time. Having made a navigational error, the captain of the Albion landed far north of the intended destination and put ashore at Matagorda Island. After reaching the mainland, the Albion passengers were led over-land and across the Guadalupe River at Mesquite Landing by McMullen, to the Refugio Mission, also located in the Power-Hewetson Colony. On learning of the arrivals at Copano and the mission, Power and Hewetson became furious. They requested the authorities to have them removed, but McMullen and McGloin dug in their heels and filed smoke screen lawsuits to bide their time while erecting permanent buildings at the mission.

While the suits were in progress, McMullen and McGloin began to bring more colonists to Refugio.

On December 31, 1829, the Albion arrived again with more Irish colonists. Another shipload of Irish colonists arrived on the same vessel in March 1830. By the middle of that year, the colony was becoming well-established, and crops had been sown. Then, the Mexican authorities came down heavily on the side of Power and Hewetson and ordered McMullen and his settlers to vacate the mission. Many of the families at Refugio had no desire to relocate, and they vented their anger at McMullen. However, by the end of 1830, the old Spanish mission of Refugio was largely abandoned.

McMullen and McGloin had moved most of their people to their own colony on the Nueces River by the fall of 1830. In 1831, the town of San Patricio de Hibernia was founded on the banks of the Nueces River just west of what they believed was the line separating the two Irish colonies. Later on, Power and Hewetson would lay claim to San Patricio. They were not successful in their claims, but more accurate surveys taken at a later point indicated that San Patricio de Hibernia did indeed fall within the boundaries of the Refugio colony. On October 24, 1831, a few land titles became official in San Patricio for the first time. In 1833, the schooner Messenger arrived on the Texas coast with more Irish colonists from New York, but the captain refused to land due to heavy seas and returned to New Orleans. Only two of the families on board returned from Texas to New Orleans. In 1834, a new group of immigrants arrived from Tipperary, Ireland, and settled in San Patricio.

Initially, the colony prospered and on April 28, 1834, the town council of San Patricio de Hibernia was established. However, as time played its part, the colonists became disenchanted with the slow pace at which land titles were being distributed and towards the end of 1834, some of the residents were making their way back to Refugio where titles were being issued at a much faster pace. Most of the remaining colonists were finally issued titles and town lots in June, July and August of 1835. The two Empresarios themselves were not given the amount of land they had hoped for and wound up with only three sitios and three laborers (13,816.2 acres) plus two rincones or corners on the Nueces River. Litigation against the Republic of Texas for more free land introduced years later was unsuccessful.

Back at Refugio, an application by Power and Hewetson dated April 21, 1830, for official control of Refugio mission lands met with evasiveness from the then Governor Viesca. Viesca’s term in office was short-lived: he was succeeded by Jose Marie Letona, a man who was solidly in the pockets of Power and Hewetson. On April 12, 1821, Power and Hewetson made another application for in the mission and its lands. This application was followed promptly by a state decree numbered 177, placing all extinguished mission lands under state control. On May 25, 1831, Governor Letona granted all Refugio mission lands to Power and Hewetson. He also gave them permission to build a town at the site of the old mission.

The Empresarios were still not out of the woods and opposition mounted from every conceivable angle including the colonization commissioner, General Teran. However, the State Governor continued to support them against all opposition. Eventually, their opponents took the matter over the head of the Governor to the Supreme Government in Mexico City. On December 3, 1831, Aleman, the Vice President of Mexico, made the decision to rebuff the opposition and support the State Governor public. On March 10, 1832, the Governor issued a decree placing Power and Hewetson in possession of their lands. He also gave them an additional three years to complete their contract for bringing families to the colony.

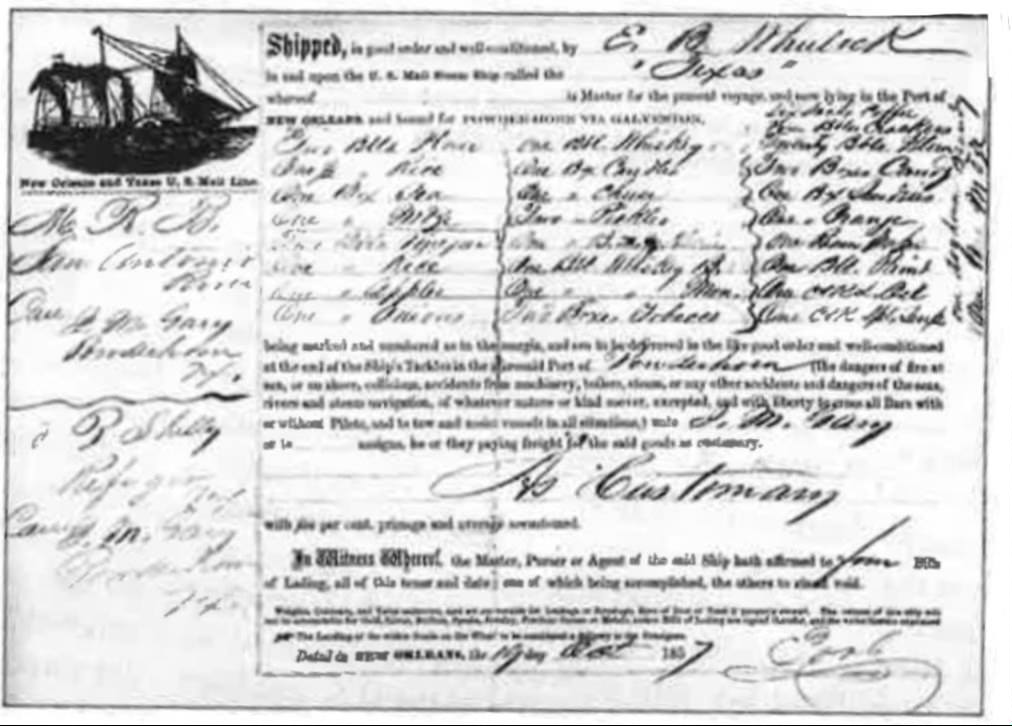

Power left Aransas, Texas, for his native Wexford on April 17, 1833, in search of colonists with particular skills. Most of the original families and/or single people who decided to emigrate came from his own locality of Ballygarrett. After sailing from Wexford to Liverpool, they departed that city for New Orleans aboard the S.S. Prudence on January 8, 1834, where they were to be quartered until Power arrived later to transport them to Texas. Many of these early arrivals made their own way to Texas, where they were assisted and quartered by the Portillas, Power’s in-laws, and an earlier established Irish settler, John Dunn.

Power himself left Liverpool on March 12, 1834, aboard the S.S. Heroine with additional colonists. The Prudence departed Liverpool around the same time on her second voyage with more colonists who disembarked at New Orleans on April 21, 1834, ahead of Power’s vessel. When Power finally arrived in New Orleans, he was dismayed to learn that many of his people from the Prudence had died from cholera while others were deathly ill. The survivors were furious at Power and demanded to be transported out of that city immediately.

Eventually, he was able to get them aboard two schooners, the Sea Lion and the Wild Cat, which departed New Orleans for Texas on May 15, 1834. Both vessels ran aground near Port Aransas, Texas, where many of the passengers already infected with cholera succumbed to the deadly disease. Some were buried on Mustang and Saint Joseph’s Island and about 250 at sea.

The survivors, which now included young children who had lost their parents and parents who had lost their children, were ferried across Aransas Bay to Copano on the mainland. In late May and early June of 1834, they arrived at Refugio only to find it filled with grain for the cavalry from the militia unit at nearby Goliad.

Although a militia captain and his men came later and laid claim to the mission buildings, the matter was settled diplomatically and colonists were eventually able to use the buildings. The Power-Hewetson colony already had some old Irish settlers within its confines; an area near the San Antonio River where several Irish families lived was called Fagan’s settlement and a section of San Antonio Bay was called Hynes Bay. These earlier settlers were of immense help to the newly arrived Irish. But many of the established Mexicans also did their part in making the new arrivals feel at home.

Land titles and town lots were distributed within reasonable time frames at Refugio and a town council was established in July of 1834.

The lot containing the Old Mission was given to one John Shelley. Power later bought the site and immediately donated it to the Church. Power and Hewetson received five leagues of land on Matagorda and Saint Joseph’s Island plus an additional 4.5 leagues on the San Antonio River. They purchased an additional 44 leagues bringing their combined total to fifty-six leagues (247, 984. 8 acres). Discontent at the settlement was rampant, and many of the settlers vented their anger at Power. At least eight families left Refugio for New Orleans after a short sojourn. Still, the settlement prospered, but the prosperity was short lived due to the Revolution of 1836.

When Santa Anna, Mexico’s best-known President, came to power, he adopted a policy of centralization taking much of the power away from the states. His plan met with stiff opposition from many prominent Mexicans including Governor Agustin Viesca of Texas and Coahuila as well as some army units. However, most of the opposition came from the Anglo American colonies of Texas as well as the two Irish colonies allied with them.

By the establishment of the “Committees of Vigilance and Safety” at each Anglo colony, as well as the two Irish colonies, the English-speaking colonists were apparently preparing for a complete break with Mexico while pretending to be upholding the Mexican constitution. After a unit of the Mexican army under General Cos passed through Copano, Refugio, and Goliad in 1835, these committees swung into action and were successful in overpowering local Mexican militias at Goliad and Lipantitlan near San Patricio. Most of the battalion who took Lipantitlan were Irish.

These were short lived victories and soon a new Mexican army under General Urrea would enter Texas. With most of the Irishmen in the fields preparing for battle, the women and children had to be evacuated from the two Irish colonies. General Urrea defeated the rebels at San Patricio, Refugio, and Goliad. At Refugio, a whole battalion containing several Irish under Captain King were slaughtered. This was followed up with a massacre at Goliad in which the cream of Irish youth of both colonies under James Fannin lost their lives. While this was going on, Indians and bandits were looting and ransacking Refugio and San Patricio.

Meanwhile, another army under Santa Anna was moving northward to the west and attacked the old Spanish Mission of San Antonio de Valero more commonly known as the Alamo in downtown San Antonio. After a 12 day siege, the Mexicans scaled the walls and annihilated the defenders. Of the 188 rebels killed at that battle, 44 were Irish and 12 were Irish born. Santa Anna’s forces failed to link up with General Urrea’s and he was defeated at the Battle of San Jacinto between Galveston and Houston on April 12, 1836. Texas had won its independence from Mexico, but the trials and tribulations were not over for the Irish of Refugio and San Patricio. Later incursions into Texas by units of the Mexican army would cause both colonies to become deserted on at least two other occasions. It was not until 1845, when Texas became the 28th state, that both colonies became fully inhabited again.

A General Council, which in effect would later become the government of Texas, was formed shortly after the appearance of General Cos. Each municipality was allotted two delegates. General Sam Houston visited Refugio and induced Power to allow him to run for delegate from that colony. With Power’s backing, he was elected. Refugio would later get two additional delegates, as volunteer soldiers were quartered there from different parts of the U.S.

When Governor Viesca attempted to join in with the revolutionaries, he was basically told he was not wanted and advised to leave for the U.S. When he attempted to sell his large land holdings, he was told they had already been expropriated and given to others. Destitute and bitter, he then left for the U.S. The committee then appointed its own provisional governor and Lieutenant Governor. McMullen then became President of the General Council.

In many respects the Irish, or at least their leaders, could be con- sidered traitors to their adopted country. While it is true that they were harassed by local and state officials on a myriad of occasions, the people who mattered including the Vice President of Mexico always came to their assistance.

No such accommodation was afforded them by the Republic and/or the State of Texas at later points in time. Power and Hewetson lost almost one hundred and ninety-five acres of land which they had rightfully purchased during the Mexican era by a ridiculous decision of the Texas Supreme Court. McMullen fared no better in similar proceedings.

Not all of the Irish threw in their lot with the Anglo Texans. Refugio had a handful of dissenters and San Patricio many more including one of its mayors. Hewetson was the only one of the four Irish Empresarios to champion the cause of Mexico. Later on during the Mexican American War, an Irish battalion led by John Reilly would take the side of Mexico. Most of Reilly’s men were deserters from the U.S. Army, but some came from the Irish colonies of Texas. They were defeated in the Battle of Churubusco in modem day Mexico City in 1847. Ironically, the defeat came at the hands of a Mexican division known as the Spy Division who had defected to the American side.

The written accounts in English of the skirmishes between the Mexicans and the Irish or Anglo-Texan colonists are notoriously biased. Prevarications constantly portray the Mexicans as being more cruel than their Anglo and/or Irish counterparts. Such innuendoes do not stand up to serious historical investigation. If anything, the Anglo and Irish colonists were the early aggressors. The events at Goliad and Refugio, when several Irish and Anglo-Texans lost their lives, are commonly referred to as massacres, while the early victories of these same groups at Goliad and Lipantitlan are classified as glorious victories with bodies of the enemy strewn in all directions.

Besides Refugio and San Patricio de Hibernia, the City of San Antonio also had a distinct or identifiable Irish community. A section of that city became known as the “Irish Flat” in the latter part of the 19th century. Three Irish Parishes also came into being around this time. The first of these was Saint Mary’s which was established in 1852. This was followed by the Sacred Heart Parish in 1874, and Saint Patrick’s in 1890. Many of the Irish also served as elected officials in city government. Except for a brief period, the Callaghan dynasty held the mayoralty from the late 1890s to 1911. John McMullen, one of the founders of the San Patricio colony, was a San Antonio Alderman at the time of his assassination in that city on or about January 21, 1853.

Despite the adversities, there are success stories associated with the Irish in Texas. Thomas O’Connor, a native of Wexford and a nephew of Empresario James Power, left an estate valued at two million dollars when he died in 1887. His son, Dennis, would go on to own several ranches in Texas totaling almost a half million acres. In time, the O’Connors would become the richest Irish American family. Through purchases from the state and other colonists, Power and McMullen would at different times own hundreds of thousands of acres. When Hewetson died in Saltillo, Mexico in 1870, he owned 642,000 acres.

Irish cohesiveness has no doubt dwindled in Texas since colonial times. However, most major cities in Texas still have Irish social and cultural organizations. At least eleven Saint Patrick’s Day parades are held throughout the state each year. In general, the Irish have contributed like many other ethnic groups in the formation and development of the Lone Star State.

Editor’s Note: This article was originally published in the January / February 1998 issue of Irish America. ⬥

Leave a Reply