Playwright Martin McDonagh, all the rage in London, comes stateside.

Only Shakespeare has matched Martin McDonagh’s record: to have four shows running concurrently on London’s West End. This past summer McDonagh’s The Cripple of Inishmaan opened at The Royal National Theatre, while his Leenane Trilogy -The Beauty Queen of Leenane, A Skull in Connemara, and The Lonesome West – played at London’s Royal Court.

All four plays received spectacular reviews and enjoyed sold-out houses.

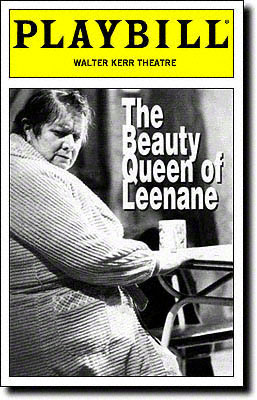

As with most West End hits, America beckoned. In February, The Beauty Queen of Leenane, featuring all but one of the original cast, will open at New York’s Atlantic Theater under the stewardship of director Garry Hynes, who originated the trilogy at the Druid Theatre in Galway.

In March The Cripple of Inishmaan, with an Irish American cast and Tony-award winning director Jerry Zaks, will take part in the Joseph Papp Public Theater/New York Shakespeare Festival.

Theater critic Fintan O’Toole, writing in The Irish Times, called the Galway premiere of McDonagh’s Leenane Trilogy “one of the great events in contemporary Irish theatre; one of the most auspicious debuts by an Irish playwright in the past 25 years.”

Such recognition would take a lifetime of work for most playwrights, but Martin McDonagh, now all of 27 years old, wrote eight of his major plays by the age of 26.

He was born in the Irish working-class neighborhood of Camberwell, South London, to a Galway father who worked as a builder, and a Sligo mother who worked as a part-time domestic. The family spent summer holidays in Ireland and McDonagh’s parents moved back to Lettermullen, Connemara some years ago.

McDonagh visits his parents frequently, and Connemara and the west of Ireland figure greatly in his plays, but in a Time Out inter- view he was quoted as saying, “I’m not too keen on roots.” He continues to reside in the family home in Camberwell, with his brother John, who is two years older.

McDonagh left school when he was 16, and spent the next three years reading books and watching TV and films. He told Fintan O’Toole that he “went into writing in the first place to avoid having a real job.” He began by writing short stories and TV scripts, which were rejected, along with 22 radio plays, by the BBC, “six in one day.”

McDonagh claims to have been unfazed by rejection. “I knew that what I was writing was good. It was definitely better than a lot of the stuff I was hearing on the radio. I think you get to a level where you realize you’re good and nothing can stop you,” he told Time Out.

“Healthy ego or not, McDonagh might have languished in the land of the unheralded forever, were it not for Garry Hynes, the famed director of the Druid Theatre. After three years as artistic director of Dublin’s Abbey Theatre, Hynes returned to the Druid and was “knocked back” in her seat by McDonagh’s work. “I asked to see new scripts,” she said in a recent interview at the Atlantic Theater. “After reading two of Martin’s plays it was clear to me that here was an extraordinary, striking talent. They seemed like plays from the 1930s or 40s. The kinds of plays Ireland prided itself on and was no longer writing. But Martin’s work also had a modern element.”

Asked how someone who was not bom in Ireland could write an authentic Irish play, Hynes explains, “Martin is not an exile, not a returned emigrant but an outsider, born and living outside Ireland, and being an outsider is important. There’s a unique mix of familiarity and strangeness.”

Is he authentic? “He’s no more authentic, if you want to use that word, than was J. M. Synge, who also mythologized the west of Ireland. The Ireland he encounters provokes his imagination. It’s the imagination of him that counts.”

As far as the playwright is concerned, he told one London publication, being born outside the country is a plus. “It’s easier to write about things from a distance, especially when you just want to tell stories, which is all I want to do.”

And what stories they are. Beauty Queen (which won over a half-dozen major awards in 1996, including the coveted George Devine Award and the Evening Standard Award for Most Promising Newcomer, and last fall won the Best Production Award at the Dublin Theatre Festival), is set in a dank, damp cottage in Connemara, and on the face of it, is an unassuming family drama about a mother and middle-aged unmarried daughter who continually snipe at cach other. The play takes on the elements of a Greek tragedy, however, when a man enters the picture to woo the daughter.

The second play of the trilogy, A Skull in Connemara, is about a grave digger who must disinter his wife’s body as some local gossips suspect him of having murdered her.

In The Lonesome West, the third play of the trilogy, two brothers, after years of petty squabbling, are thrown together by the death of their father but continue to have enormous disputes over the slightest thing.

Simple description, however, can- not convey the unexpected twists and turns of McDonagh’s plots, the richness of the language, the idiosyncratic and compelling characters, the typically Irish fusion of pain and laughter. It is the lengths to which the playwright takes his characters’ intense desires that lift McDonagh’s trilogy out of the ordinary, may one say “kitchen sink” dramas, and into the realm of almost mythic dimensions.

McDonagh’s writing melds harsh, bitter dialogue with flights of lyrical language, combining traditional storytelling with savage, macabre humor. Beauty Queen is both deeply moving and hilarious, often at the same time, a rare achievement for any writer. But he still finds space for a character to mourn the loss of Gaelic, and to heighten the perennial unsettledness: “That’s Ireland, anyway. There’s always someone leaving.” And, wails the suitor, who must work in London, “When it’s there I am, it’s here I wish I was, of course. Who wouldn’t? But when it’s here I am… it isn’t there I want to be, of course not. But I know it isn’t here I want to be either.”

The Cripple of Inishmaan forms part of another trilogy, the Aran Trilogy. In this play, set in 1934 on the island of Inishmaan off the coast of Connemara, young Cripple Billy, orphaned in infancy under mysterious circumstances, is abused and belittled by the villagers. McDonagh uses the true story of a visit by filmmaker Robert Flaherty to the neighboring island of Inishmore to shoot Man of Aran, giving Billy the opportunity to plead for a role. Sent to Hollywood for a screen test, he is rejected in favor of an able-bodied actor and must return to his roots where he meets an unhappy end. The play melds eccentric characters, black humor and pathos. McDonagh himself loves film and has recently written a road movie thriller script for Paramount, called First Day Out of Folsom (a notorious southern California prison).

Meanwhile, Beauty Queen is enjoying something of a world tour. The play has been translated into German, a production recently opened in Finland, and another company completed a highly successful tour of the islands off the west coast of Ireland. Not forgetting The Cripple, which recently played in Zurich.

For all his success, McDonagh says he thinks playwriting is one of the least interesting artistic forms. But he does admit to liking David Mamet’s work-a-felicitous choice, inasmuch as the Atlantic Theater was founded by Mamet (and actor William H. Macy), several of whose plays were made into films (another aspect that appeals to McDonagh), including Glengarry Glen Ross and American Buffalo. The young McDonagh has also seen movie actors Martin Sheen and Tim Roth on stage. In total, however, he has seen only 19 or 20 stage plays – four of which are his own.

No less a theater luminary than Richard Eyre, former artistic director of London’s Royal National Theatre, whose own forebears S hailed from Galway, has said, “McDonagh has sprung from the womb a fully-fledged playwright.”

Although McDonagh (he refused to be interviewed for this piece) gets some negative reviews for his personal behavior -he’s been called arrogant and had at highly publicized run-in with Sean Connery at an awards presentation, hurling an unprintable epithet at the film star-he is lauded by his supporters.

Garry Hynes says, “He knows what works on stage. He’s terrific to work with. That’s all I care about.” And Todd London, artistic director of New Dramatists, a New York-based playwrights organization which offered McDonagh a fellowship on an exchange program from the Royal Court, calls McDonagh “a very sweet guy.” Gregory Mosher, former director of Lincoln Center Theater and producing director of Circle in the Square, who specializes in working with new writers, and who directed McDonagh’s play reading at New Dramatists, says, “I found him to be the easiest person in the world to work with, profoundly courteous to everyone he dealt with.” As to reports of arrogance, Mosher says: “Why not? It’s a difficult business to break into. If this man weren’t aware of what a good writer he is he’d have to be brain dead.”

McDonagh’s work gets overwhelmingly positive marks. Neil Pepe, artistic director of the Atlantic Theater, set his cap for Beauty Queen after seeing it at London’s Royal Court. “It was incredible writing, a beautiful production, and the acting was spectacular.” Although Broadway offers beckoned, McDonagh opted for the more intimate Atlantic and Public theaters.

Rosemarie Tichler, artistic producer of the Public Theater, said, “McDonagh is one of the bright new voices of Ireland. It’s a play [The Cripple] we have loved for a very long time and a playwright we are extra- ordinarily interested in.” Noted Broadway/ film director Jerry Zaks, who will direct The Cripple, said, “I only do things that I fall in love with when I read them. It’s a beau- tiful play. It has humanity, humor, language … I’m looking forward to sharing my response with an audience.”

Meanwhile, Martin McDonagh had some advice for aspiring playwrights in a recent interview with Young Times:” Don’t go see plays. I’m serious. Decide for yourself what you think a play should be, write it and see what happens. You should also read a bit, And don’t listen to any advice whatsoever. I think you should know if you are good or bad and nobody should change your mind. Just get better at what you are doing.”

Editor’s Note: This article was originally published in the January / February 1998 issue of Irish America. ⬥

Leave a Reply