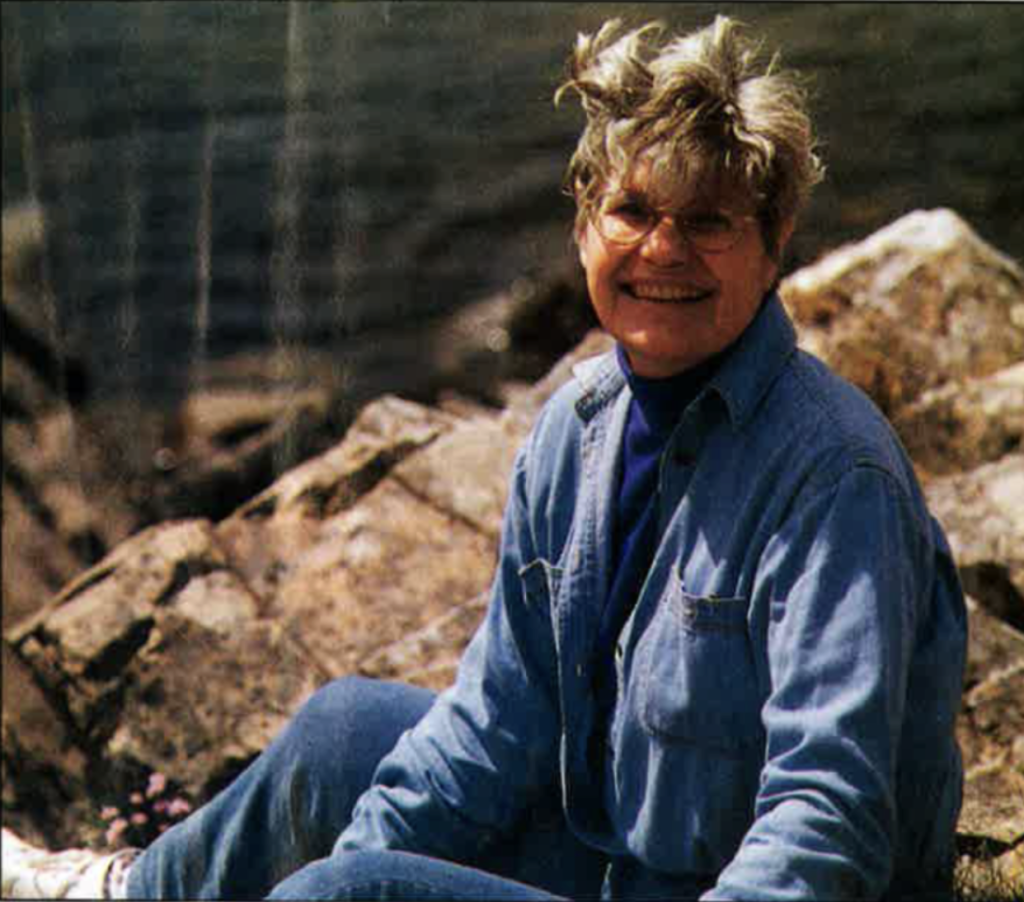

Betty Wald visits Ireland for the first time in search of her grandmother’s home in Kilmacillogue, County Kerry

In all the long years of Sunday visits to my grandmother’s apartment in the Bronx, she never talked about Ireland. There were no tales of a far-off land for a child’s imagination to grab hold of, to elaborate over the years, making family myths to pass on to future generations. There were no stories of farms and famine and families left behind. There was no music to hear or dances to learn or poems to recite. When I was a child, her silence made me feel there must be something shameful about being Irish. It was a silence my parents perpetuated, trying to be more American than any American could be, trying to be without roots, newly sprung from the New York soil.

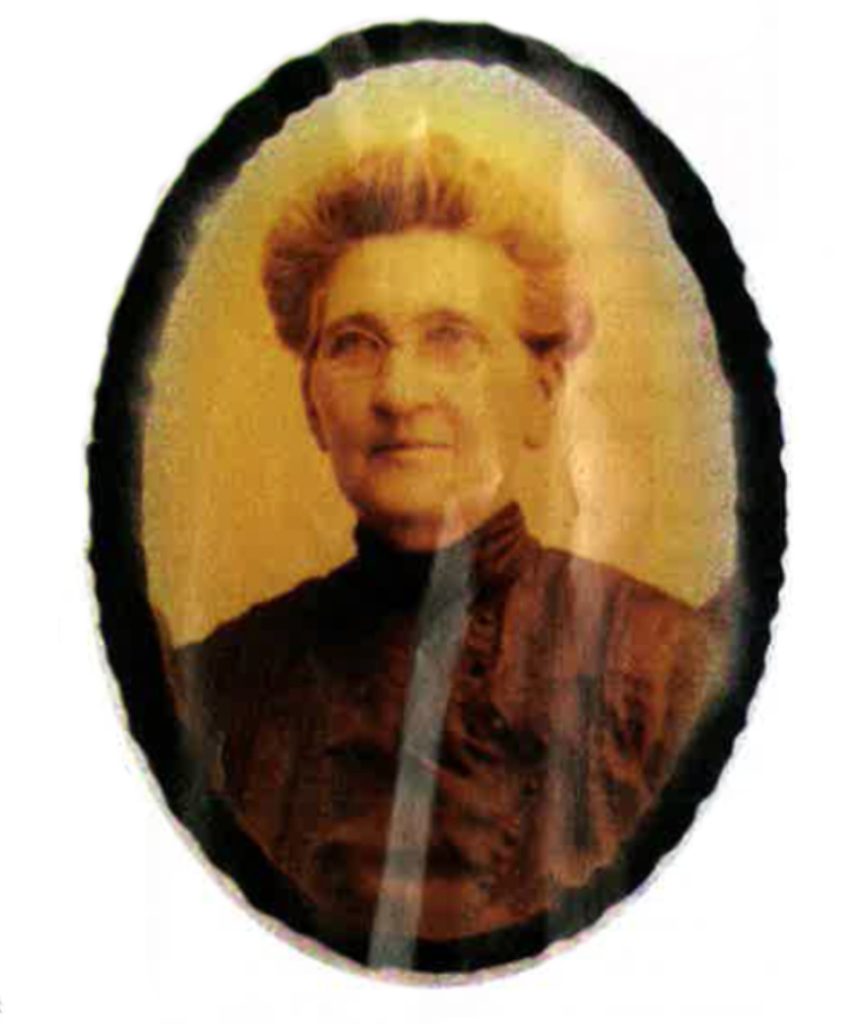

I am named for this grandmother, Mary Elizabeth, who left Ireland at seventeen, taking along her young niece and nephew. Their parents, her oldest sister and her sister’s husband, had gone on ahead to New York to find work and a place to live.

I thought about that voyage as my husband Arnold and I made plans to visit Ireland last spring. What courage it must have taken for so young a woman, leaving behind mother, father, sister, brother, traveling steerage, responsible for two young children, and sailing forth to an unknown land. She knew she’d never see her family again and since they couldn’t read or write, the leaving was complete.

She could never have imagined that I would one day make the return voyage, like some sort of reverse pilgrimage, kissing the ground she walked away from, never to return. And never to speak about.

Now, with this trip we were so eagerly planning, I might have the opportunity to find the places my grandparents came from, and perhaps to penetrate the mystery of my ancestral home shrouded for me by unanswered questions as much as the island is shrouded by fog and mist.

I gathered what scanty information I had: the memory of being told that my grandmother came from Dingle in Kerry and my grand- father from Cahirciveen. I knew the names of my grandmother’s parents and had a note saying her parish church was in Tuosist, a place that didn’t appear on any map that I had. We arrived at Shannon Airport in sunny weather, and had to immediately master driving on the left side of the road.

After two days in County Clare, we made our way south to Kerry. We drove on narrow roads, past stone walls enclosing grazing sheep and cows. We saw cliffs and ocean, bleeding hearts and rhododendrons, all growing wild, and along the roadside lovely blue flowers I had no name for. We stayed near Caragh Lake, surrounded by the McGillycuddy Reeks, the highest mountains in Ireland. It was not far from Cahirciveen and an hour’s drive from Dingle.

In Cahirciveen, a charming market town, people smiled when I said I was searching for my grandfather’s family.

“Now what name might that be?” asked Regine, an artist whose craft shop we visited. “O’Connor,” I said.

‘Ah, there’s plenty of O’Connors,” she said. “Go down the street to O’Neil’s hardware. He’s a lovely elderly man who knows a lot of history. Maybe he can help.”

When we found Mr. O’Neil and I told him my grandfather was born about 1860, he said, “I’m old, but I’m not that old. But go see the chemist, Jeffrey O’Connor. Maybe he can help. He’s two blocks down the street. And good luck to you.”

Mr. O’Connor was a bit discouraging. “You’ve got too little to go on, I’m afraid,” he said. “But try Michael Murphy at the old Barracks around the corner. He knows a lot about genealogy. Maybe he can help.”

Mr. Murphy was out. It began to rain and we decided to call it a day. “Maybe I’ll have better luck with my grandmother’s family, the Sheehans,” I said.

The next morning I had an inspiration. I opened the phone book and looked under Churches. There was a listing for Tuosist.

“Where are you located?” I asked the priest, Father McCarthy, when I finally reached him by phone late in the day. I was surprised to hear him say, “We’re in Lauragh, on the Beara Peninsula, a good distance south from you. Tuosist is a parish and covers a wide area, but it’s nowhere near Dingle. Now tell me the names of your grandmother’s parents and when you think she may have been born.”

After he searched through old records in Latin, Father McCarthy sounded excited. “I’ve found her!” he said. “Here she is in the church records for 1857. Mary Sheehan, baptized the day she was born, February 15. It cost three shillings, three days wages back then. The family lived in Derryrush.” “I never heard of Derryrush, Father. Where is it?”

“Take out your map and I’ll show you. It’s not a village, just a scattering of houses. Do you see Kilmacillogue Bay? It’s not far from there. The old church in which she was baptized is near there too, what’s left of it.”

The next day, in bright sunshine, we set off for the Beara peninsula and I was glad that it was Arnold driving on the left side of the difficult narrow roads that wound along the mountainside. By Moll’s Gap in Killarney we stopped to rest and take pictures. In the pretty town of Kenmare, we had a late pub lunch of salmon salad. Never did salmon taste so good and so fresh. Then finally, late in the afternoon, we drew near the area the priest had told me about.

“Oh look,” I said to Arnold as we were driving along a country road past green farmland stretching up the side of the mountain. On a rise up ahead I saw the ruins of an old stone church and a small cemetery. “I bet that was her church.”

We walked among the graves, all Sheehan family members. Sheep grazing nearby paid me no mind as I tried to make my way down the hill through high grass and tangled bushes to reach some very old headstones. I was sure my great-grandparents were there, but the writing on the tombstones was worn and impossible to read.

“Betty, we’ve got to go on, it’s getting late,” Arnold said and I reluctantly got back in the car.

“Father McCarthy said to look for Kilmacillogue Bay,” I said, the map open on my lap. Soon, the blue-green waters of a bay stretched before us. There was a place on the road to pull over and I scrambled down to the shore. I’m not sure why, but as I sat among gray rocks and small pink wildflowers, I had such a feeling of connection and peace there. My grandmother may have come here as a girl, I thought. She must have lived somewhere nearby. While Arnold took pictures, I sat a while, imagining her there, surrounded by such beauty.

Looking for Derryrush, we drove on till we came to a little village called Bunnaw, where there was a pier and some lobster boats, a grocery store and Sheehan’s pub. It was in the pub that I told the proprietess, Helen Sheehan, of my quest.

She called to an ancient looking man who sat in the back. He reminded me of my father. Like my father, he was also a bit deaf. “Doesn’t that sound like Dan Sheehan’s folks?” The old man agreed and she sent us on to the next village, Ardgroom, where in another shop I was told that Dan Sheehan lived “just up the hill a bit in that old white house on the left.”

It was well after five thirty by the time we knocked on Dan’s door. A shy, sweet man about sixty answered the door. He was dressed in work clothes and boots, just after coming in from the farm, he said. The wife was still out gathering mussels. I introduced myself and told him Helen Sheehan thought we might be kin. His blue eyes widened and he gave me a curious look.

We spoke of the time when my grandmother lived there and exchanged names and bits of information.

“It was a terrible time in those days,” he said, referring to the famine. “So many had to leave. They were taken by horse and cart on the long trip to the boats in Cobh. That’s a port near Cork City. There was many a tear shed here, many a tear.”

We talked about all the different Sheehans, and he told me about the Brigids and Jameses in his family, some who had stayed, some who left.

“Now, do you know your great-grandmother’s name?” he asked.

“It was Kate Sullivan.”

“There were Sullivans in my family, too. Why, I think we must be cousins,” he said with a smile.

“The wife will be home soon. Will you stay for a drink?”

I hesitated, longing to say yes, but I was concerned about our driving those narrow mountain roads in the dark.

“Oh, we’d love to. You’re so kind. But I’m afraid we have to go, it’s after six already and the trip back will be a long one. And tomorrow, we leave for Cork City, our last stop before returning home.” How I hated to leave. There was so much more I wanted to know.

We exchanged phone numbers and I promised I would call his wife the next day. At the door he shook our hands. “You’ll have to come back for another visit to Ireland,” he said.

“I will,” I said and I knew I would have to, for I could see my search had just begun.

On the way back I told Arnold that I wanted to stop one more time by Kilmacillogue Bay. I sat there looking out at the water and then over to the hills. How could they bear to leave this beautiful place? I asked myself. But I knew the answer. Hunger and poverty can render beauty meaningless. “You can’t eat the scenery,” my grandmother used to say.

I imagined her as a barefoot girl walking along the edge of the water, digging for clams, looking up at blue sky, hills patchworked with stone-edged squares of farmland, all different shades of green, and dotted with white clumps of sheep. Then sitting where I sat, perhaps thinking about America.

“I’ve come to say good-bye, Mary,” I said in a whisper, and I saw her turning to smile at me.

Just before she died, my grand-mother had looked shocked when I told her that I thought she didn’t talk about Ireland because there was something shameful about it. “Shameful?” she said. “Oh no. It’s that it was so terrible to have to leave.”

And it wasn’t until I arrived on these shores and stood on ground my grand-mother had stood on, and saw this awesome beauty for myself, that I understood the pain remembering would bring.

The next day we left for Cork. On the map, we saw that Cobh, the port that Dan spoke of, was on the way. The city had a European look, with multicolored buildings one after the other lining the shore, and atop a steep hill above them loomed a grand gray baroque Cathedral.

We stopped at the old railroad station where there was a dramatic exhibit about the emigration. What caught my attention was a statue outside the exhibit. It was of a teenage young woman of the late eighteen hundreds, her hands on the shoulders of a young boy and girl. The boy is looking out to the sea and pointing, while the young woman’s head is slightly turned as if taking a last look at the shore. It seemed a fitting conclusion to our trip to stand there, and with tears in my eyes, I thought of Mary Sheehan with her niece and nephew, waiting to board a ship bound for New York, never to return. But for me, it would be different. I promised myself that I would come back.

Editor’s Note: This article was originally published in the January / February 1998 issue of Irish America. ⬥

Leave a Reply