Many of the thousands of Irish babies adopted in the U.S. in the ’40s, ’50s, and ’60s are reclaiming their roots. Emer Mullins reports.

℘℘℘

In a quiet convent outside Dublin, an elderly nun is in possession of a veritable Pandora’s Box relating to one of the most controversial periods in Irish social history.

Sr. Patricia Quinn used to work at St. Patrick’s Guild in Dublin, a mother and baby home and adoption society run by the Sisters of Charity under the auspices of the Archbishop of Dublin.

It was from this place that hundreds of Irish babies born to single mothers were transported to America, usually when they were about two years old. The mothers had to wean their children before they were adopted. One woman recalled how the nuns restricted the hours she and other mothers could spend with their children as the adoption neared. “I was weaned from him like from three times a day to twice a day to once a day,” she said of her 20-month-old son. “Not just from breast feeding, from seeing him.”

Sr. Patricia Quinn has a photographic record of many of those babies, tucked away in a cardboard box. This historical montage contains photos of babies sent to New York, Chicago, and other American cities. Many of these babies went on to happy lives in America, and some not so happy, as evidenced in their reluctance to discuss their childhood.

The mothers, on the other hand, housed in homes such as the Magdalen Asylum run by the Sisters of Charity, commonly known as the Magdalen Laundry because of the work the women had to do, often went on to marry, the secret of their cherished baby kept to themselves. Some actually married the father of their baby, as in my own sister’s case, where my parents never revealed to their nine subsequent children that we had a sister adopted in America.

In some cases, the children were fostered in Ireland. One woman recalled how, at the age of three, she came downstairs one morning and was introduced to her 10-year-old sister for the first time.

The emotional consequences of many of those adoptions are only now being revealed.

One baby whose photograph Sr. Quinn possessed was Miles Patrick Lawless. Born in St. Patrick’s Guild in 1961 to an unwed mother, Miles was sent to Lafayette, Louisiana, to Doc and Lou Dauterive, where his name was changed to Daniel. He grew up as a French Cajun, with French-speaking parents, and had a very happy childhood.

But his bright red hair always reminded him of his ancestry — and when he grew older he wanted to find his birth mother. “I was a red-haired blue-eyed boy,” Danny said. “I was always curious about my roots, and when I decided to search, my adoptive parents didn’t celebrate. But they were always supportive, and always told me I was adopted. They had kept my Irish passport, and were always honest.”

Danny and his wife, Tammy, who live in Montana where Danny runs a local public television station, decided to try to find his Irish mother. The search led to Sr. Patricia Quinn, who was instrumental in reuniting mother and son. “I found the nun who arranged my adoption,” Danny explained, referring to Sr. Quinn. “She had a big ledger book of names. She has a box of pictures of kids from the States that families sent to her after the kids were adopted. She had a picture of me, and she found my birth mother.”

Within three months, Danny knew who and where his mother was. “Compared to what everyone else goes through, I was either very lucky or too stupid to know better,” he remarked. When Sr. Quinn contacted Danny and said his mother would meet him, he was scared but happy. “I spent my whole life wondering,” he remembered. “And here I’d found out my history. I grew up in the Cajun culture, although every St. Patrick’s Day I had a `Kiss Me I’m Irish’ T-shirt. I always said I was an Irish Cajun, which meant I could drink twice as much!”

Danny, Tammy, and their first of two sons, Miles Lawless Dauterive,set off for Dublin. “It’s like going to a funeral or a wedding and meeting people you haven’t seen for 20 years — you know you’re related but you don’t know them,” said Danny.

It was November 1991, 30 years after Danny was born in Dublin. He was overjoyed to find his mother, but they do not have a close relationship. “We spent a few hours there and since then we’ve sent Christmas cards and written letters. But I wouldn’t say we have a close relationship,” Danny explained. “I’d like to visit again and I asked her to visit Montana but she wouldn’t. I think she still feels it’s a stigma, to have given birth out of wedlock.”

Although Danny’s parents got married after his adoption, Danny believes his mother, whom he did not wish to name, still reflects the attitudes of those times; of a staunchly Catholic society which treated pregnant single women as aberrations, hid them from view in Church-run homes, changed their names and sent their babies abroad to keep their “shameful” secrets buried.

Estimates suggest that thousands of babies underwent this fate, growing up in foreign countries with new identities and new lives. Ireland’s Department of Foreign Affairs announced a year ago that its archives contained as many as 2,000 files, the hidden secrets of a generation of Irish women. The role of the Catholic Church, which ruled over the government in this matter, has been exposed. There was no such thing as separation of Church and State.

The patriarch of the Catholic Church in Ireland from 1940 until 1972 was Archbishop John McQuaid, who ruled supreme over matters of Ireland’s morals. As John Cooney, a biographer of McQuaid’s, wrote: “The record shows his primary concern was the upbringing and indoctrination of children either in a Catholic home or a Catholic-run orphanage.”

McQuaid was behind the directive governing the adoptions by Americans of Irish Catholic children between 1948 and 1962 which stripped a mother of all future rights to her child.

“There were very few choices,” said Fr. John Dardis, spokesman for the Church, when asked about the directive which saw mothers sign away their babies. “I think we weren’t as aware then…how can you judge the 1940s with the insights of the 1990s?”

McQuaid also saw to it that the adoptive parents had to promise to bring the child up in the Catholic faith and with a Catholic education. But perhaps the most outlandish part of this Faustian bargain, for the adoptive mother, was that she had to prove she was not using contraceptives, “an obsession of McQuaid,” according to Cooney.

A form entitled “List of Documents to be submitted to His Grace, The Archbishop of Dublin and Primate of Ireland by Prospective Adoptees Abroad” required “medical certificates for both prospective adopters, stating their ages and certifying as to their general physical and mental health and that they are not in any way shirking natural parenthood.” The form also stipulated that “there should be no publicity at any stage in connection with the adoption.” And the directive specified that the adoptive mother give up work.

There was no adoption legislation in Ireland at this time; in fact, McQuaid blocked prospective legislation put forward by the Irish government in 1944 and 1948. Records show that de Valera’s government tried to introduce adoption law at the end of World War II. The secretary of the Department of Justice at the time, S.A. Roche, sought McQuaid’s advice on “religious problems” involved in the adoption of “destitute children.”

In March 1945, McQuaid said while legal adoption was not against the tenets of the Catholic faith, he had not seen any proposal which would safeguard the faith of the children. “If my advice be sought I should urge that no step be taken in respect of Catholic children — and you know what a proportion that category entails — without referring the matter to the Catholic hierarchy.” The government surrendered its role in the face of the Church’s power.

When legislation was finally introduced in 1952, McQuaid vetted every word so that his army of Catholic children would not be led astray by adoptive parents. The Adoption Act included the clause that the adoptive parents must be “of the same religion as the child and his parents, or, if the child is illegitimate, his mother.” This was found to be unconstitutional in 1974 and overturned by the court.

Fr. Colm Campbell was ordained in Ireland by Archbishop McQuaid and for six years worked as a priest there while this policy was in operation. He said he feels guilty to this day when he thinks about the un-Christian way in which the Church treated these women. But he also wonders what the alternative would have been had the church not helped the pregnant girls. “Looking back now, we can see the human misery it caused,” he said. “But at the time we really thought it was for the best.”

So thousands of babies were shipped from the shores of Ireland from a number of institutions, often carried in the arms of air hostesses on Ireland’s national airline, Aer Lingus. Meanwhile, the mothers were left to grieve and wonder alone.

Kathleen Brennan, nee Quinn, originally from County Longford, was one such mother. At the tender age of 16 she discovered she was pregnant. She did not know where to turn, and ended up in the mother and baby home in Castlepollard, County Westmeath in April of 1951. There she remained for a year, during which time she gave birth to her daughter, Rosaleen, in September 1951.

“We were given a name so we couldn’t identify each other if we met on the outside,” Kathleen remembered. Her given name was Doris. “We got up every day at 5.30 a.m. and went to 6 a.m. mass,” she said. Kathleen was assigned to work in the nursery with the newborn infants — almost all of whom were to be adopted. “I remember lines of cribs with all those gorgeous babies,” Kathleen said softly.

Of her own little girl’s birth, Kathleen said: “When Rosaleen was born she was tiny. I just remember robbing her little hands and legs constantly.”

The Nursing Sisters of the Sacred Heart, who ran the convent, allowed the women to spend brief periods with their babies during the day, but at night they were kept in the nursery, overseen by other women.

“They had us nurse the babies as newborns, but took them away at night. I was working in the nursery and people would come up to see the babies — there were always visitors looking,” said Kathleen. “Some babies were adopted before they were a month old. The ones who were two and three and four were on a different floor. It was hard if a family didn’t take a child because then they were sent as orphans to a county home.” These children would often work the land for local farmers without pay.

Many mothers were given only hours’ notice when their baby was to be taken. Kathleen Brennan was told two days in advance of Rosaleen’s adoption. When her turn came, Kathleen seems to have blocked a lot of the memories out. “When I let her go,” she said, “I was given two days’ notice. She was all dressed in pink, and there were two little boys in blue. I remember thinking `she’s so tiny.'”

Kathleen did not know where her daughter was being taken. She said it was her decision to have her baby adopted because she couldn’t “take the flak” from her parents, but she had no idea that Rosaleen would be taken to America. She, like countless other girls, was forced to sign the horrendous “relinquishment form,” swearing on oath that “I hereby relinquish full claim forever to my child…and I hereby surrender the said child…and I understand never to make any claim to the said child.” The child was relinquished to the care of the Reverend Mother in question, so the parent had no way of knowing the baby’s final destination.

Rosaleen’s journey took her from Castlepollard to a family in Wichita, Kansas, where she became, to all intents and purposes, Mary Ellen Hammer. Rosaleen Quinn, as far as the Church, the community and her mother were concerned, was gone forever.

Mary Ellen, however, had other ideas. Her adoptive mother, Marie, was tragically killed in a car crash in Kansas when Mary Ellen was four, and her father, Melvin, remarried, a woman who later had children of her own. From an early age, Mary Ellen was aware she was not their natural child. “I remember being very young and I asked my father why my parents gave me away,” she confided. “He lied and said they were very poor. I said, `But, Daddy, I wouldn’t have eaten very much.’ And he just cried and cried.”

Mary Ellen said her childhood was great, and she appreciates that she may not have fared so well had she remained in rural Ireland. But as she grew up her heritage became very important to her, especially when she had children of her own. She wanted to find her mother. She, like many others, did not consider searching for her natural father. Many adoptees told me they believed their mothers had been abandoned once they became pregnant, or simply had a brief relationship with the man, so they never considered searching for their natural fathers.

When Mary Ellen’s search began, it was thwarted by the very institution responsible for her predicament — the Catholic Church.

When Mary Ellen visited St. Patrick’s Institute in 1987 the nuns said they could not help her. “I contacted Sr. Gabriel of the Sisters of Charity [who had arranged the adoption] and she said they couldn’t help. They said their contract was not with me,” Mary Ellen related. The nuns argued that their client was the mother, not the child, and they could not breach that confidentiality. “She had all the records right there but she would not give me any information and she would not attempt to make contact with my mother on my behalf,” Mary Ellen continued. Sr. Gabriel told Mary Ellen that her mother would have to request a search, knowing that the mothers were forced to swear that they would not do so.

Mary Ellen did not receive any help from the religious in Ireland, although she had organized a thank-you party for the Catholic priest who arranged some 20 Irish adoptions in that area, including her own — Father Michael Blacklidge, whose sister was a nun in Ireland.

Undeterred, she continued to search, and contacted the same nun, Sr. Gabriel, nine years later, facing another rebuff. She enlisted the help of the Belfast-born immigrant chaplain, now in New York, Fr. Colm Campbell. Mary Ellen’s marriage to Graham Hall had taken her from Kansas to New York as a successful banker. Fr. Campbell, in turn, contacted a friend in Belfast, who tracked down the Quinn family in short order. To Mary Ellen’s astonishment, she discovered her mother had lived in New York since 1958. “It was like fate,” she said. While she presumed her mother had remained in Ireland, Kathleen presumed Mary Ellen was in Ireland. They met for the first time in 35 years in New York on October 17, 1996. They spent Christmas together with their respective families, and a growing bond between mother and daughter is emerging.

“I think her coming into my life has given me the benefit of her wisdom. She is my confidante, and she gives me patience and total acceptance,” Mary Ellen said. Kathleen is overjoyed with her daughter. A second daughter died in a subway accident at the age of four before Kathleen had a third. She also has two sons. “I remember I had a dream where Rosaleen was a housewife in Dublin and I went to visit her. She wasn’t very friendly,” she said wryly. “When she tracked me down, I heard from a nun in Belfast. She called and asked me if I remembered 1951. I said yes, and then she told me. My daughter was in New York.”

When the two were reunited, Kathleen, almost instinctively, started petting Mary Ellen’s hands, stroking them endlessly. “She just loved to touch me,” Mary Ellen said. “I had never been looked at so lovingly. Now it’s funny because I see I have all these inherited Irish traits. I’ll go to the wall for a cause, and I never knew where I got that from. Now I know.” Mother and daughter meet at least once a week, and are fast becoming friends. “Just last week,” said Mary Ellen with a laugh, “she asked me if I had all my own teeth!” She assured her mother that she did.

Irish American adoptees are finding that avenues of search have opened since their situation was highlighted in both the Irish and U.S. media in 1996 and 1997 as a result of some horrific tales about life in the Magdalen Homes, the Church-run industrial homes for unmarried pregnant women and mothers, and as a result of people deliberately being given false information when they tried to search.

Many people profess themselves willing to help, but, unfortunately, reports have emerged from adoptees of unscrupulous individuals who see other people’s heartache as a way to benefit themselves.

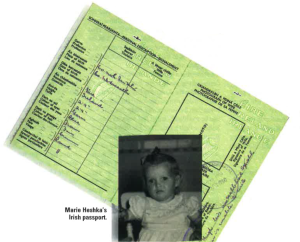

One Irish American adoptee who reported such problems was Marie Heshka, whose search for her birth mother began 14 months ago. Made undertook an enormous amount of research when she began to try to trace her mother, and her efforts led her to reach out to Ireland to help. There she contacted Anne Kane, a woman featured on ABC’s 20/20 because of her involvement in helping adoptees search. However, Marie claims that instead of helping her, Kane deliberately misled her. “She told me she found my mother, she had my birth certificate and my mother’s name was Margaret,” said Marie. None of this was true. Kane, she claims, gave her false details, but asked her to make a donation to NORCAP, a totally legitimate adoption counseling group based in England.

Kane has since asked adoptees for a $250 “registration” fee and then required more money for further “services,” Irish America learned.

Marie Heshka was so angry over Kane’s behavior, she fired off an angry letter to NORCAP, urging the group to investigate its affiliation with Kane. “I spoke with [Kane] on numerous occasions over a five-month period and wrote several letters in 1996. During this time Ms. Kane supplied little helpful information and told me some blatant lies,” wrote Heshka. “I do not make this charge lightly. I am writing this letter of complaint because Ms. Kane continues to find more victims.” Irish America could not reach Ms. Kane. “She will refer you to an adoptee she has helped, but she won’t tell you about the nine others she has burned,” Heshka said. Caveat emptor.

Meanwhile she continued her search on her own. Born Maria Goretti O’Neill in Castlepollard, County Westmeath, she grew up in Flint, Michigan. Her adoptive mother, from Belfast, had married an American in the U.S. Army whom she met in Fort Knox, Kentucky. Marie’s parents separated two years after she joined them, and she grew up in a single-parent household with an adopted brother, Barry, also from Ireland.

“At school we were the only immigrants, and we were sent to speech therapy because of our accents,” Marie remembered. “I probably had a nice Irish brogue. I always felt different, and when my adoptive mother died in 1988 I found letters and correspondence from Ireland, and decided to search.”

After doing some preliminary research, Made ran into closed doors, and let the matter drop. But at the end of 1995, she and her husband were sailing in the Caribbean when she heard a radio broadcast from England — a BBC show about the Magdalen Home in Galway, one of a number of notorious industrial homes run by nuns in the 40s, 50s and 60s. The first St. Mary Magdalen’s Asylum was established in 1798 and placed under the care of the Sisters of Charity in 1833. “It provides in every respect for 120 penitents, who contribute to their support by laundry work,” said Thom’s Directory of Ireland in 1960. The horror story that was life for the women in these Magdalen laundries, as they were known, emerged in the past year. Tales of physical and sexual abuse at those and other state and Church-run orphanages abounded in the press, leading one order of nuns to advertise its public apology in a daily newspaper.

“I just couldn’t believe it,” Made said. “I thought, `Could that have been my mother?’ When we came back to the U.S. my husband said, ‘Just do it,’ and so I began again in January 1996. I lived at the Central Research Library and the Latter Day Saints — I went at it full-time.”

Marie eventually contacted Sr. Mary Sarto in Ireland, who freely told Made her mother’s name, and offered to drive to her home in County Leitrim to uncover more information. “She told me my birth weight and time of birth,” Made said happily. In January of this year, Marie made contact with her mother, who now lives in England. She wrote to her, and her mother responded with another letter, the first line of which read: “I was overjoyed to hear from you.”

Marie’s mother, whose identity she wishes to protect, told her daughter she had tried to search for her 17 years ago, when Made was 21. “She was told she couldn’t, that I would have to initiate the search,” Made explained. “She said she was 21 when she became pregnant, that it was the first time she had sex, that her father beat her, threw her out of the house and disowned her. She was at Castlepollard for two years, and her mother visited her there once behind her father’s back. She said the pregnant girls were never allowed to leave the grounds, and all their mail was read. She was given a name and a number to identify her. She said even now she could not write to the nuns, because some of them were very unkind.”

Castlepollard, at that time, was certified to hold 130 mothers. “My mother knew her baby was going to the U.S.,” Marie added. “We [adoptees] used to say we were born in the belly of a Pan Am jet.”

Marie, too, is overjoyed to have made contact with her birth mother. “I thought about having a T-shirt made with `Irish American Adoptee: Born 10-15-1958 — Are You My Mother?’ written on it,” Marie confided with a laugh. “The problem for people searching is they don’t know where to go or whom to trust,” she continued. Marie is one of a growing number of people who are reaching out to others in the same situation to offer help — at no cost.

Adoptees often fear rejection while searching for their birth mother or father. And the ones being sought sometimes do not want to be found. According to John Lawton of the Department of Foreign Affairs in Dublin, which has custody of the 2,000 confidential adoption files discovered in 1995, the department has received letters from birth mothers saying “under no circumstances should their names be given out.”

For Irish women, in particular, their circumstances during those years were made insufferable by their communities, a direct result of the influence of the Church. The shame and stigma they were made to feel lingered for years in many cases. Many went on to marry and rear families without ever disclosing their secret, and feared that their past would catch up in the shape of a knock on the door.

This is perhaps best illustrated by a story related to me by an Irish woman involved in helping people search. It was the heart-breaking tale of a pregnant teenage girl, abandoned by her puritanical parents and taken in the back seat of a car in the dead of night to a mother and baby home in County Cork. When her baby was born and adopted, this girl remained at the convent. She had nowhere else to go. She spent her entire life working for the nuns as an unpaid cleaner and housekeeper. When she died a couple of years ago, a nun contacted the woman’s sister to break the news and make arrangements for her funeral. Her family still did not want to know. After a period of lengthy persuasion on the part of the nun, the woman’s sister agreed she could be buried in the family plot. Secretly. The woman’s body was removed from the convent in a hearse in the dead of night — almost exactly as she had entered: in silence, in secrecy and alone.

Babies who died in infancy or were stillborn were buried anonymously in graves in convent grounds, never having had an identity. The Irish government again surrendered to pressure from the Church and shut its eyes to the situation. One such graveyard can be found at Sean Ross Abbey in County Tipperary, and one Irish adoptee was so moved by what she saw there she is planning a memorial service for those unknown children in 1998.

The effects of “the American baby trade,” as one observer sarcastically described what happened in those dark years, will reverberate in Ireland and the U.S. for years to come.

While many of the children may have been better off financially or even emotionally because of their adoption, many more suffer the agonies of being without a history and a heritage. However, when a baby’s adoption crosses ethnic lines, the effects are even worse.

One such child was Nancy Ellen Giambalvo, born in Brooklyn in 1961 to an Irish mother. Nancy was adopted by a Jewish family in Brooklyn, and when she was six she was convened to Judaism in a ceremony which she did not understand. She was sent to Hebrew classes after school, where she did not feel comfortable. When she married, 12 years ago, it was to a man of Catholic and Jewish descent. Her husband, Andrew, recalled how Nancy’s parents asked before their wedding if he had had a bris [a ritual circumcision ceremony for male infants] and a bar mitzvah. “They knew I was half Jewish but they asked for proof,” Andrew said in disbelief. “Yet they knew Nancy had been adopted, she was originally Catholic and had been converted [to Judaism], and they didn’t say anything about that.”

Nancy is very hurt at what she sees as her parents’ deception. “I was always mistaken for being Irish, and I would get snappy,” she said. “I remember being at temple when I was little, and people would say to my parents, `Look at the shiksa’ [Jewish term for Christian]. I didn’t know what that meant, and they always told me it meant `cute.'”

Nancy’s husband calls her the `lost Celt.’ She remembers staying indoors on St. Patrick’s Day, because her red hair led to the assumption that she was Irish.

“When I was going out as a teenager, Jewish guys never asked me out,” she said. “They knew I was different, and I always felt different. But Irish or American guys would ask, and they were amazed when I said I was Jewish. I have this Celtic look, I suppose,” she said wistfully.

Her confusion over her identity was compounded by the lack of information from her parents, and Nancy became ill because of her situation. “I got sick in December and my doctor said I was perfectly healthy,” she said. “Then they kept asking if something was bothering me, and my parents asked if something was wrong. I said yes — I don’t know anything about my biological mother.” Nancy’s parents passed on a bizarre story about how she came to the family, which Nancy does not believe. She does know she was born to an Irish woman in Prospect Heights Hospital in Brooklyn, delivered by a Dr. Hyman Fishman, and has a copy of her birth certificate, which was deliberately altered.

“There are more papers on my car than there are on me,” Nancy said wryly. “All I have are an altered birth certificate, a letter from a rabbi saying I was successfully converted, and my marriage license.” Nancy’s parents, who said they paid her mother’s medical expenses while she stayed at the St. George Hotel in Brooklyn, refuse to give her any more information, so she is proceeding with her search without them. “They said my mother was in her 20s, she smoked Camel cigarettes, but they couldn’t remember her name. I remember my father saying to me, ‘You don’t look Jewish’ and it was eating him up. They always said to me, `If we didn’t adopt you, who would?’,” Nancy recalled. “I feel like I am some dirty little secret they have to cover up.”

Despite her anguish, Nancy can laugh at her predicament. “My cousins wanted my photograph so they could model their nose jobs after mine,” she said with a chuckle.

Nancy, like Marie Heshka, has visions of a public appeal for help.

“I think I’ll have a T-shirt made that says: `I’m O-Dopted: Do You Know Me?'” Nancy said. “Maybe someone will recognize me or listen to my story.”

The walls erected by the Church and government in Ireland are obviously crumbling — and a generation of Irish children are seeking answers. There are calls for the establishment of a national contact registry in Ireland, and this, apparently, is under consideration. But one American woman wants to take things a step further. Kathy Houlihan from Allentown, Pennsylvania, whose reunion with her natural mother in County Donegal was featured on ABC’s 20/20 show The Lost Children of Ireland, visited the unmarked graveyard in Sean Ross Abbey in Roscrea, County Tipperary containing the babies’ remains.

Kathy, a professional fund-raiser, was so moved by what she saw there that she has already begun to raise funds in the U.S. for the erection of a monument at the site. She has written to Irish President Mary Robinson to ask for her support.

“A memorial should be built,” she said. “There are probably hundreds of unnamed babies in graveyards in Ireland given the mortality rate in the 40s and 50s. It broke my heart — it was like we were the bad blood and no one wanted us. I want recognition for them, because it’s sacred ground.”

Kathy wants to organize a sponsored walk for families and adoptees in Ireland in the summer of 1998 to raise money for a suitable memorial. “I want to send a peaceful message, too,” she added. “It’s over, as far as how single mothers were viewed in those days. I’m not trying to confront the Church or the government; this is about reuniting families. After all, we are Irish citizens and we want our country to embrace us.” ♦

Leave a Reply