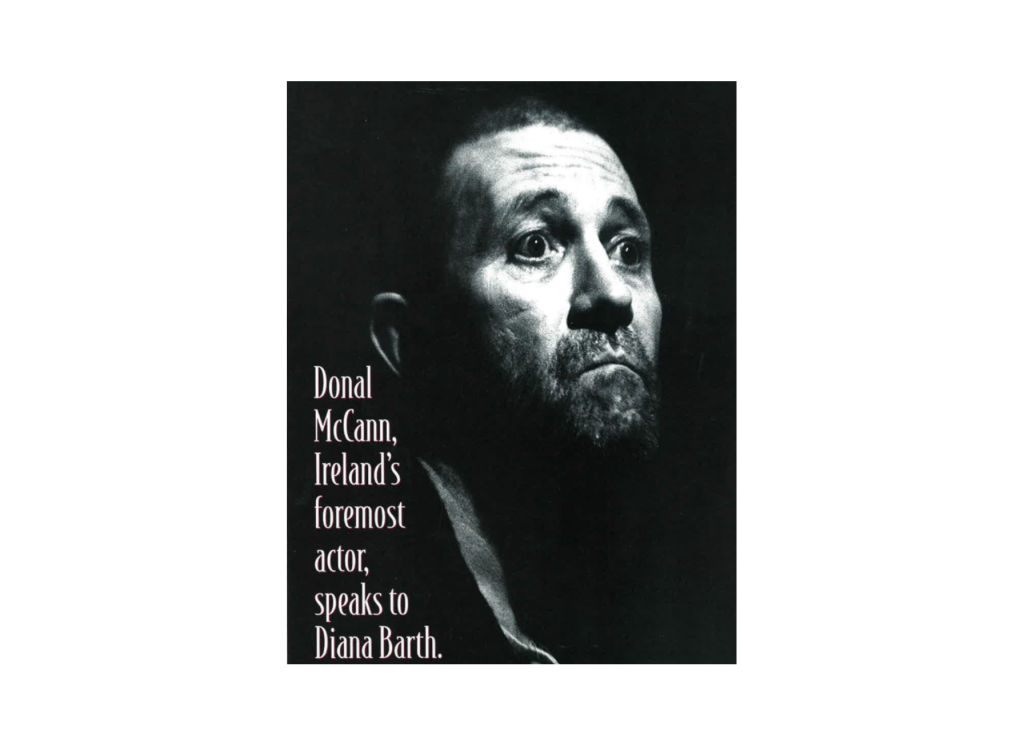

Although the brilliance of actor Donal McCann is well-known abroad – even a Dublin cabdriver praised him as a “great actor” to this writer on the trip from the airport to the city center — McCann’s name seems a well-kept secret in the U.S. That oversight should be corrected when Donal McCann opens, in the starting role, in Sebastian Barry’s luminous, moving, poetic memory play The Steward of Christendom at the Brooklyn Academy of Music later this month.

McCann, who garnered ecstatic raves in London and Dublin, won the London Critics Circle 1996 Best Actor Award for The Steward of Christendom while the play itself was named Best Play of the Year. The New York engagement will mark the end of an almost two-year journey which began in London’s Royal Court Theatre, co-produced with Out of Joint and directed by Max Stafford-Clark.

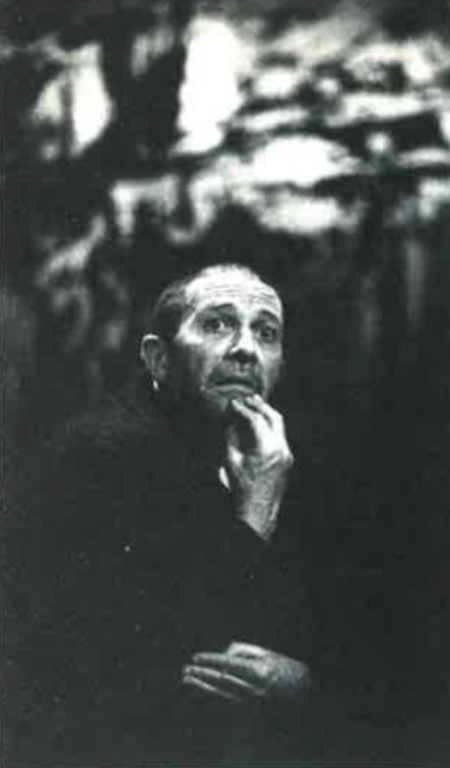

The intense, Dublin-born Donal McCann spoke with Irish America over coffee in the elegant lounge of that city’s Westbury Hotel. Asked how his association with Steward had come about, he replies, “I’d been working on a very good television script up in West Yorkshire, and they sent me The Steward of Christendom. One read of that and I said I’d go with this, whatever happens to it. It was just so powerful to read, wonderful. I bored people, talking about it.”

That was probably the last time Donal McCann bored anyone in connection with Steward Here are just a few critical comments on his performance at Dublin’s Gate Theatre: “McCann’s performance is extraordinary.” “Mr. McCann has re-established his pre-eminence among the great actors of the world…a performance that demands not to be missed.” “No actor living could better this portrayal.” And in London: “McCann’s imaginative sympathy makes this the performance of the year.”…”performance of braising power…of compelling beauty.” “…monumental..” “There is no more moving piece of acting in London.”

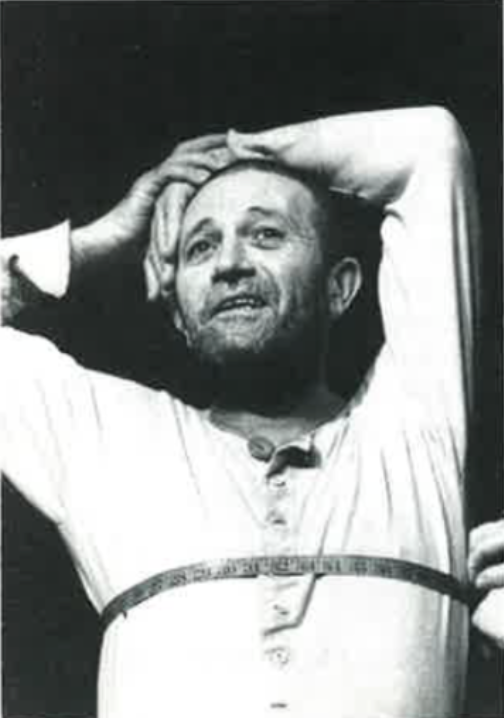

Without question the role of Thomas Dunne is a felicitous match for McCann’s talents. First seen as a demented 75-year-old, then a younger, strong and vital policeman, Dunne, the actual great-grandfather of playwright Sebastian Barry, was the last Catholic head of the Dublin Metropolitan Police during the political upheaval in Ireland in 1922, when Irish independence was wrested from Britain. In one scene Dunne must prepare to hand over the reins of Dublin castle, for which he had held full responsibility, to the legendary revolutionary Michael Collins. Having given his loyalty to Queen Victoria, Dunne came to be looked upon as a traitor to Ireland.

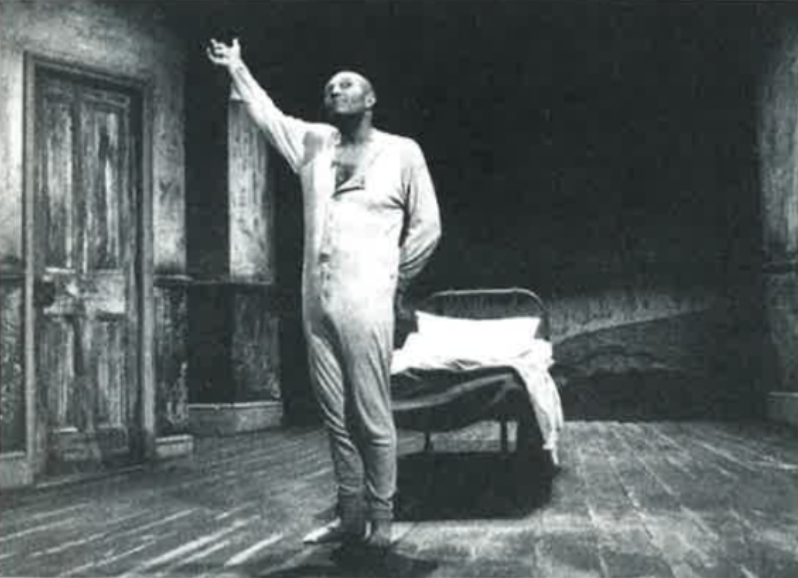

The play begins as Dunne, ten years later, in a County Wicklow asylum, stubble-bearded and wearing grimy long-johns, relives fantasies of his former happy life with his wife and children. It is the portrait of a broken and tragic man, racked with shame, regret and loss. But it is the familial aspects — Dunne’s love for his wife of the “mole-black hair” and their four saddened children — that wrings the heart and gives the play its piercing poignancy and eloquence.

McCann, who is in his early fifties, comments, “The whole rehearsal period was to turn that thing, that I knew was there, and Sebastian knew…I just knew it could work, you know? There were people who doubted it. Not anyone associated with the production…I didn’t for a moment think that it automatically would work, but I knew that it was possible for it to work.” He takes a deep puff on a cigarette. “They put me in a straitjacket in this play. Sometimes I don’t get myself in the optimum position and…all the ranting…all this becomes very…tiring.” A pause. “I can honestly say I never worked harder on anything in my life.”

Does he play sports to keep in shape?

“No, and I have a bit of a bad back as well, or so I’m told by a doctor I met last year in Donegal. It really goes back to playing rugby at school. The doctor said, `Do you feel this thing here?’ He played in the same position I did, known as the hooker.” McCann’s eyes twinkle. “So I was a fourteen-and-a-half year-old hooker. And I have a bad back to prove it.”

McCann originally set out to be a journalist, but his father, John McCann, was a successful playwright with the Abbey Theatre, so there was always a pull in young Donal’s mind toward theater. “I had liked acting. I think I always wanted to be an actor.” Later, he took over a leading role in one of his father’s shows at the Abbey, and the die was cast. Of early training: “Most of us [young aspirants] seemed to find ourselves doing tiny pieces or bit parts or crowd work with the Abbey. Years ago the Abbey did short plays in Gaelic, because there was a certain amount of money available from some Gaelic organization for that purpose. Because there weren’t many such plays, what you got were adaptations. There’s a play by Chekhov called The Bear and I remember appearing at the very end of that with a hay fork or a rake.” It is clear from McCann’s tone that he recognizes the irony of his remarks. Indeed, as he warms up to the interview, his love of a good story and his skills as a comedian come to the fore.

Suddenly the hotel’s paging system announces the name: “McCann.” He quickly says, “That’s not me. They want Eamonn McCann, who’s a far more famous person than I am. He’s a writer, a very passionate civil rights person. He’ll probably be writing about your man’s visit here.” [McCann was referring to President Clinton’s imminent visit to Dublin.]

But what of Donal McCann’s skills as a writer?

“At the moment I’m exercising myself very severely trying to think of 200 words for one of the papers about the favorite book of the year that I’ve read. I find 200 words daunting. They ask me occasionally to do that.” He continues, “A good letter in the letters page is frequently the best read in the newspaper.”

Although he downplays it, his dedication to his work is keenly evident. With regard to becoming an actor he says, “I think if you have the intention, or indeed the vocation, you’ll end up doing it.” But he always injects humor, as if being too serious might spoil things. A story he tells of his early performance as Hamlet illustrates:

“Did it years ago, around the corner at the Gaiety Theatre. If Shakespeare were alive today…[he looks skyward helplessly]. It was a brave idea of making it a Celtic Hamlet, which is fair enough. You could get away from using posh accents and things like that. But I honestly didn’t realize until halfway into rehearsals that they were serious about changing place names. And that immortal line became `Something is rotten in the state of Ireland.’ It was sad.” He paused. “It’s one of those things that might give a more sensitive person nightmares but I actually can’t stop laughing about it.”

Of course McCann is sensitive. But his persona conveys a contradictory mix of almost gruff strength and softness. His rich, flexible voice can project anything from a rasp to delicate lyricism. If called upon, he could play a poetic longshoreman or a refined truck driver. The famed Italian filmmaker Bernardo Bertolucci said of McCann: “When I saw him in Steward at the Royal Court, he looked like a criminal; he had a quality of danger. I knew then I wanted him to play the sculptor in my film [Stealing Beauty, released last summer, to fine personal reviews for McCann].”

That McCann is so different in every role may account for his lack of familiarity to the general public. He was the tender husband to Anjelica Huston’s wife in John Huston’s film The Dead, an adaptation of James Joyce’s great short story; for BBC he did the ruthless Judge Brack in Hedda Gabler opposite the noted and controversial Irish actress, Fiona Shaw, who just recently made her New York theater debut.

McCann has made a name for himself playing the great Irish roles: the crude Boyle in Sean O’Casey’s Juno and the Paycock, won him rave reviews (the Gate Theatre production was part of the first New York International Festival of the Arts); the earthy Estragon opposite Peter O’Toole’s Vladimir in Samuel Beckett’s Waiting for Godot; the self-involved mystic Frank Hardy in Brian Friel’s Faith Healer and others. Although the last-named play, in which McCann appeared at the prestigious Long Wharf Theatre in New Haven, Connecticut, got roves from the New York critics, McCann wryly said, “On the last day, when I opened my big envelope of Connecticut reviews, they hadn’t liked it at all. It was like Faith Healer could cure your insomnia.” How many actors would admit to that? But McCann likes a good laugh, even at his own expense.

As to the possibility of McCann ever settling in Hollywood, to expand a burgeoning film career: “Why would I want to go to Hollywood? All you get near there is money, and the temptation to adopt a life style which is going to force you to do a lot of rubbishy work to maintain it. I think it’s kind of silly.” McCann chooses to reside in a quiet Dublin suburb.

Because there are parallels to King Lear in Steward — a mad father with three daughters — many people have suggested McCann tackle that role. He comments, “It’s a kind of silly yardstick. It has never bothered me. I would certainly veer towards trying to take on, or be in good productions of, say, Chekhov, or O’Neill.”

When it was noted that another journalist wrote that McCann was becoming a specialist in tragic, middle-aged Irish men, McCann scoffs, “I think you’re quoting from an interview [dryly] with a writer of fiction. But he’ s carried away. In my opinion I don’t think anybody has ever done anything like Steward before because I don’t think there’s ever been a play like this before. It’s a very special piece of writing.”

He continues, in measured tones: “I think it’s very important to bring it to New York. I think it’s very important that this man’s play be seen there.”

It was, then, a wise choice to decide to do Steward?

Donal McCann replies, “I don’t think there was much choice in it, to be honest, you know? Once it was there, I couldn’t not do it.”

Leave a Reply