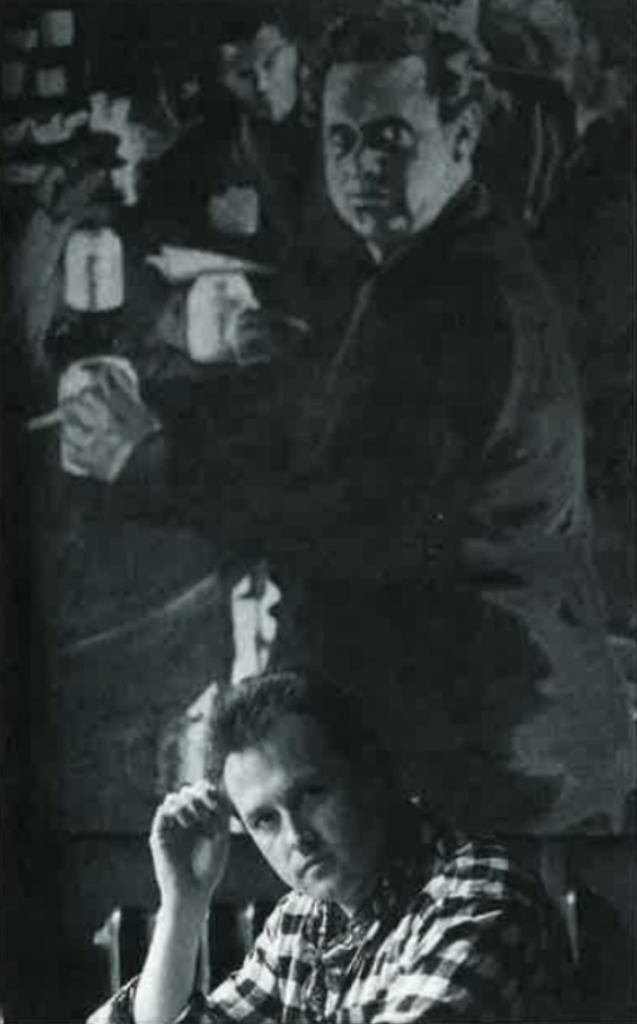

Colum McCann, one of the hottest new Irish writers on the literary scene, talks about his career with Laoise MacReamoinn.

Colum McCann, the New York-based Dublin-born writer who burst on to the American literary scene last year with his first novel, Songdogs, which the New York Times called “powerful, strong and sure,” and whose first collection of short stories, Fishing the Sloe-Black River, has just been published to great acclaim, laughs as he tells of his first visit to the U.S. at the “completely green, know-all” age of 18.

“I’d got a job in the Universal Press Syndicate, who do the Doonesbury cartoons, among other things. I was a gofer and sandwich-getter. I’ll tell you a true story. They sent me down to get all these different sandwiches. There was Reuben, there was rye, pastrami, swiss, basically there were all these sandwiches, and I didn’t have a clue. I mean, what was pumpernickel bread, for God’s sake? Anyway, the guy then asked me did I want mustard? I said, `Yeah, yeah.’ Then he said `Mayo?’ and I said, `No, no, not Mayo, Dublin.’ I swear, it’s the truth. But don’t forget these were the days of `salad cream’ in Ireland. Well, there was one of my first introductions to being really stupid and green.”

Returning to Dublin, and completing a journalism course, McCann worked as a reporter and feature writer for the Irish Press Group (now sadly defunct) for about three years. But he returned to the U.S. working as a taxi driver/landscaper/motel worker in Cape Cod. “I knew I wanted to write. I remember I bought a typewriter when I came over, and said I was going to sit down and write this great novel. I put a page into the typewriter, and at the end of the summer the same page was in it!”

What stopped him, he felt, was that his life lacked the wealth of experience required to write something that other people might want to read. “The thing was, I grew up middle-class in Dublin, I didn’t have a deprived childhood — basically I didn’t have anything to write about. So then I went off on a bicycle with a friend. We cycled from Massachusetts to Florida, and across to New Orleans. I spent the next two years on a bike. I cycled about 12,000 miles, and met incredible people all along the way.”

When not cycling from one end of the country to the other, he found gainful employment where he could. “I had a bizarre collection of jobs. I worked on a ranch, fence posting and the like. I was a bike mechanic, waiter, bartender, I dug ditches for fires in Idaho, and painted houses.”

After traveling through Mexico and parts of Canada, the peripatetic aspiring novelist ended up in Texas where he worked for two years, from 1982, with kids who had come out of prison and broken homes. “I was a ‘Wilderness Guide’ at this ‘Wilderness Camp,’ where for about three months we’d all live in the forest, and the kids had to build their own world — shelters, outdoor showers, toilets. They grew some of their own food, raised small animals, and then they’d go to an on-campus school and hopefully progress from there. I still get letters from some of these kids. Some are back in prison, some are in universities, some are mechanics in their local garage.”

Mexico and the West of Ireland attract me. They’re landscapes I feel invovled with, where I feel at home.“

Recalling his grueling 22-hour-day, seven-day-week work schedule, he laughs at the wonderful nature of hindsight. “Of course, it’s great now it’s past. Dealing with the kids was difficult, let’s not romanticize, but they came through it very well. As for me? I knew it was worth it. I knew there was something there.”

Capitalizing on those incredibly rich years of meeting people “who all had a story to tell,” McCann went on to university in Texas where he met his wife-to-be, found employment as a bartender, and started working on his first stories, which appear in Sloe-Black River. He had written a novel the previous year “which never got published and never will, thanks be to God. It was dreadful.” He recalls that literary legend Ben Kiely, his mentor, about whose work and character he can’t speak highly enough, “was very kind about the novel. Very kind.”

But McCann’s travels weren’t over. “Alison and I went to Japan for two years to teach English as a foreign language, and I finished my short stories. One of them got accepted into Best British Short Stories of 1993 [he raises an eyebrow at the `British’]. Up to then I’d been getting rejection letters from all over the place.”

The collection was published in Ireland and Britain in 1994 to great acclaim. Japan is also where he wrote the first draft of Songdogs, which, with only a writer’s logic, is set in Mexico and Ireland.

What is most striking in McCann’s work is the imagery, rich, colorful and startlingly vivid. He seems equally at home in the landscapes of Mexico, New Orleans, Kyoto, or the wilds of County Mayo.

“Mexico and the West of Ireland attract me. They’re landscapes I feel involved with, where I feel at home. I don’t feel at home writing about middle-class Dublin, because it’s not very interesting to me. It’s not provocative in any visual or metaphorical sense. But there’s a certain wild, strange landscape that I find attractive, which I think is why I find the tunnels so attractive.”

The “tunnels” he refers to are the subway tunnels of New York, the subject of his new novel, currently in its second draft. “I was at a party for a wonderful literary magazine called Grand Street and I met somebody there who told me that there are between two to five thousand people living in the underground subways of New York. Immediately, and again as a landscape, as an idea, it just blew my mind. I asked him if he could get me down there.”

Despite being regarded with suspicion — being a white, middle-class boy — he got to know the people of this strange nether world. What he found was a revelation. “There’s a huge identification with the oppression of the Irish in African America. The Irish and the blacks built these tunnels side by side. I spent last St. Patrick’s Day down the tunnel with these guys, some of them are my friends now. I brought a few six-packs and we sang Irish songs.

“The tunnels are sort of brutal and magical at the same time. Brutal because of the drags — hypodermics lying around. Alison used to make me take my clothes off outside the door of the apartment. Magical, well…in this particular tunnel, there are all these murals, like Salvador Dali’s Melting Clocks — 10 by 12 feet. There’s Goya’s Third of May in commemoration of the Los Angeles riots, paintings of Martin Luther King, Stokely Carmichael, Miriam Makeba, all these cultural icons, mainly of the African-American experience. It’s like going back down to the cave, Pluto’s original cave.

“This is a very American novel, there aren’t very many Irish characters, but I found I was really writing about Ireland anyway. But this is written with American rhythm, American cadence — and no doubt they’ll say, `Ah, he’s becomin’ a Yank now,’ but they’ll be surprised because the next novel — if I live that long — will be a purely Irish novel.”

Prolific hardly seems strong enough a word for this 31-year-old writer who has also just completed the screen adaptation of Songdogs and whose first stage play, Flaherty’s Window — which the BBC is also doing as a radio play — will be staged in New York in January by the Dedalus company, an Irish-American company committed to bringing new Irish plays to American audiences.

The characters who inhabit the stories in Fishing the Sloe-Black River and give them their singular haunting grace, whether in a Long Island convent hospital, a New Orleans laundromat, or the hills of County Kildare, have a common thread, a kind of hopeful longing.

“I think I’m writing about characters in exile, and that’s not literal exile from Ireland. It’s exile from communities, exile from themselves. People who are searching for a way to get back to their past, back to their roots, to some kind of elemental understanding. Even this novel that I’m currently writing has become about family, being on the outside, and excluding yourself through self-abuse, physical abuse, abuse of others, but still searching for that elemental chord. Grandfather, mother, past history. Characters that are searching for a way back to a mythical home. Like the tunnels. These are good people, they are wounded people. Wounded psychologically, socially and physically, some are war veterans. They are ultimately looking to create some kind of resurrection of themselves.”

Leave a Reply