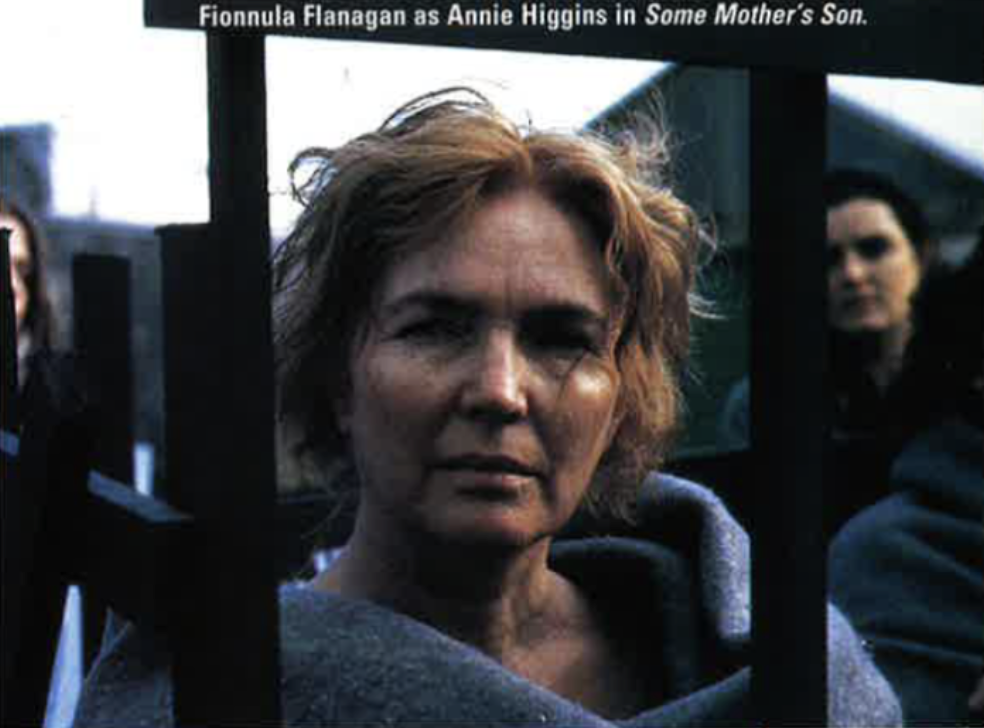

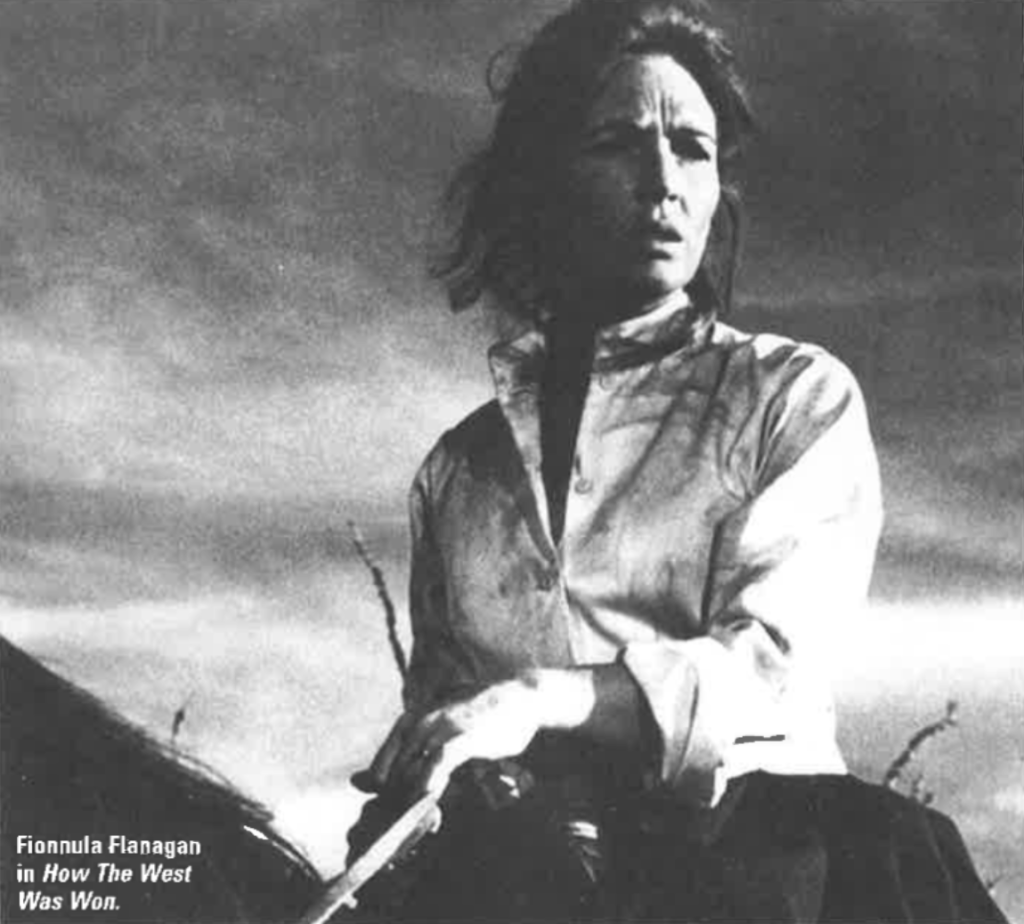

Actress Fionnula Flanagan is a beautiful woman who is not afraid to ditch the glamour if the role demands it Audiences who remember her as the green-eyed, sultry redhead in the TV series Rich Man Poor Man for which she won an Emmy, and How the West Was Won, might have a hard time recognizing her in Some Mother’s Son. Flanagan’s opening shot shows her wearing no makeup, her hair pulled back with a rubber band, dressed in Wellington boots and a man’s overcoat. She is Annie Higgins, fearlessly herding her cows through a contingent of British soldiers who are sealing off a road that leads to her farm.

It’s a powerful moment. Flanagan, who is rather slight in build, is reminiscent of Bull McCabe in The Field — a force to be reckoned with.

A consummate actress — her portfolio includes a litany of stage and screen performances, including the highly-acclaimed James Joyce’s Women, which she adapted for the stage and went on to produce as a feature film — Flanagan will be long remembered for her latest work Her performance is such that there is talk of an Oscar nomination.

The story of two mothers caught up in the Hunger Strike of 1981 which took the lives often young men, Some Mother’s Son is a powerful, emotionally-laden movie, brilliantly directed by Terry George who co-wrote the script with Jim Sheridan. Helen Mirren, who enjoys star billing, is excellent as Mrs. Quigley, whose son is also on the blanket. But in many ways this is Fionnula Flanagan’s film, and she knew it as soon as she read the script.

Much as she wanted to do the movie, however, she didn’t hesitate to duke it out with the young director before she got the part.

“It was a foolhardy thing to do,” she admits now sitting back on the couch in her suite in the New York Essex House Hotel. It’s two days after the premiere and she is recovering from a cold that has left her voice a whisper. “I wouldn’t advocate it as a way to go for any actress.”

Foolhardy or not, one senses that Fionnula Flanagan is a woman who follows her heart. And, as for the fight, it might even have helped.

“I knew she was right for the part when I heard her fight with Terry on the phone,” says George’s wife, Rita Higgins. (It’s no coincidence that the character in the movie has the same surname). “No one fights with Terry like that.”

The director, who says that the character he had in mind was “a woman who was physically big, and strong,” also knew from that first fight that the part was hers. “Once Fionnula got into it, the strength and size carne from her heart.” Helen Mirren concurs: “I think this subject was very dear to her heart. She came to the project with an enormous emotional commitment.”

Flanagan was already a highly-acclaimed actress in Ireland and England when the role of Maggie in Brian Friel’s Lovers brought her to Broadway in 1968. And it was while touring with this production that she met her husband-to-be, Garret O’Connor. The Dublin-born psychiatrist, at John Hopkins in Baltimore at the time, was brought over to the hotel by actor Eamonn Morrissey to administer to the cast, all of whom, after six months on the road, had ills of one kind or another Twenty-four years later, unthinkable in Hollywood terms, they are still together.

“I forget to include Garret,” she says, reaching out a hand to him as he passes, “because he is such an extension of myself.”

O’Connor is highly regarded for his ground-breaking work on the legacy of colonialism on the Irish psyche, and Flanagan credits her husband with bringing a larger dimension to how she saw herself and her culture. Together through the Institute For Innocence which he founded, they have conducted workshops in the U.S. and Ireland, North and South, which address healing in Irish and Irish-American Catholics.

The couple also took time out in New York to attend a meeting of the Irish Famine Genocide Committee, before heading back to their home in Beverly Hills. Two nights later, still fighting off a cold, Flanagan was performing in L.A. with Anjelica Huston, Gabriel Byrne and Gregory Peck, in a celebration of Irish poetry and prose to benefit Amnesty International and the children of the North of Ireland through Project Tomorrow.

Flanagan says that taking on the mothering role to her step-grandchild, Kalina, II, whose own mother died when she was 5, helped prepare her for her latest role. In playing Annie Higgins, she says the phrase that kept reverberating in her head was “the hand that rocks the cradle rules the world.”

Do you think Some Mother’s Son is an important movie with regard to women?

Yes, I think the two mothers in the movie represent the women in the North of Ireland who are never given a voice. They are always there in the background, they are the mothers of the boys, the heroes, the soldiers, the sons who are slotted into the role of being the fighters; it’s the women who get up every day and make lunches and who keep the faith and support their children, even when, in Kathleen Quigley’s case, they don’t approve of what their children are doing. And in Annie Higgins’ case when she knows that it probably will mean death.

So it makes a statement about them and it portrays them as thinking women, and women whose authority in their own lives is frustrated by a political system and two extraordinarily powerful institutions badgering them on both sides, one being the British government and the other being the Irish Catholic Church so that no matter what choice they make they will be ill thought of. Whether your son will live or die was an appalling choice to be faced with. To think that this was perpetrated by a government on their population in our lifetime is horrendous. [Once their sons lost consciousness the families were given the choice of taking them off the Hunger Strike.]

Then, of course, they turn to the only other institution they know where they can expect to be comforted or supported or protected, which is their church, and they are told: “It’s morally wrong for you to withhold your signature and you ought to sign.”

What is your own memory of the Hunger Strike?

When I saw the film completed, the thing that came to me most strongly was I wish I had done more at the time of the Hunger Strike. I contributed a few dollars whenever I was asked and I signed petitions but as I look back I feel I should have dropped everything and gone and stood outside the prison gate and made my voice heard, because this event in our history was so appalling that we ought all to have paid more attention. I think that many Irish people may feel the same way.

It was a very tragic time, especially for those families involved.

Overwhelming. I can understand how the families [of the Hunger Strikers] would not want to be involved in the making of the movie because of the overwhelming nature of this tragedy — they suffered so much — and to me, what the word has not taken into account is that the moment the spotlight was taken off the hunger strike and the media moved away like a flock of birds, that community was left with the shambles of that tragedy and death and mourning and destruction. Even today within the nationalist community in Northern Ireland the percentage of suicide and unemployment and domestic violence and drinking and physical and emotional and mental breakdown is extraordinarily high for a community as we measure them against communities in the modern world. You can say that that is addressed by sociologists and the department of health, but are they equipped to deal with the healing that needs to be brought into being to address such frightful destruction?

There are arguments that a fictionalized version of the Hunger Strike was not the way to go.

The choice was either to try to track the Hunger Strike as an event by doing a 24-hour documentary in the hope that everybody who had participation in it would take part, and take part with integrity, or to do a fictionalized version that could at least make the world aware of what had taken place.

People are going to try and guess who the hunger strikers are and who the mothers are, and it doesn’t really matter, because the people who are depicted are an amalgamation of different hunger strikers, and these are not two specific women, they are two from that huge crowd of mothers who put on their coats and did what they could do which was to march down the street and say their rosaries and beg their God to look down with pity on a situation — a travesty and a cruelty — that was beyond their imagination.

Does it bother you that your Annie Higgins is given second billing to Helen Mirren’s Mrs. Quigley?

Well, it bothers me as an actress because my ego comes into play and I want my character’s role to be as important as the other actress’s. But the way the picture is edited the weight of it is thrown to her character and for a very legitimate reason. She represents the audience — there has to be someone who represents the audience. My character could not represent the audience because of my authority, my politics within the story. I’m the catalyst, if you will, and the one thing that a catalyst doesn’t do is change. For all the tragedy that comes down around her ears Annie does not change and that is her great strength. Because Helen represented the eye of the audience being exposed to these events — shockingly finding out that her son is involved in the IRA — her character is ideal for being the audience guide through this and it automatically put Annie’s character in a secondary position.

Now, I can tell you as an actress I didn’t like that at all and in a perfect word I would have the lead, which is why it’s probably just as well that I wasn’t either directing or editing the picture. She [Mrs. Quigley] must change through realizing what this community is all about, and realizing that these people aren’t as demonic as she thinks. She learns that through Annie, her humanity.

In the film there’s that distance between Annie and Mrs. Quigley. What was it like in real life on the set?

I was delighted to work with Helen because I think she’s a fine actress. And I think we were perfectly cast for this. We were well matched. And when I heard I got the part I thought “Good, we’ll be well able for each other,” and even though I’d never met her I’d watched her work and we work very differently to get to the same point. I thought we’ll serve each other well, there’ll be that edge there — and part of the edge, of course, was that I was very jealous of her as an actress, of her fame, and what attention her name could command, and how everybody was mad about her and loved her, and when she walked on the set everybody smiled at her, and I was standing around like some piano in the comer in my coat and my Wellington boots glowering my discontent out at the world and probably frightening people away, and every time the director would look or smile at her I would get a stab in my heart.

So I told Helen. Once I said, “I’m so jealous of you,” then I didn’t have to be any longer.

What was her response?

She understands these things, that it is part of the work, part of the journey that you embank on. People say to me it must have been very emotional shooting that story because of the sadness of the situation for the mothers and the son, and reliving that story — it wasn’t. It had to touch depths in me where I had to relinquish ego on a level that exposed me yet again and in a way that I think benefited Annie. My husband is fond of saying that the road to humility is through humiliation, and God knows I think you learn that as an actress.

You’re obviously a very glamorous woman. Did you have reservations about playing Annie without makeup?

I knew that this would be an exposure and that it needed that, it had to have that. The yellowing of my teeth was something I had great fears about. For an American audience you want white teeth and a flashing smile because you know from television that that’s what gets you your true love and advances you in the world. So I would look in the mirror and go Ugh! this is awful. But anyone who smoked as much as Annie would have yellow teeth. I didn’t mind not wearing makeup because I thought she ought to have that weather-beaten look. I do support what Stanislavsky said about that, because when you put on the wellies, and the socks and the coat, and the sweater and the robber band in the hair, you do begin to shrug into the skin of the character, and that’s always helpful and I’m glad when I look at her now.

How did you prepare for the role?

I was privileged to be given some time with a woman whose three sons had been killed. The first one died when he was very young during the ’60s, making a bomb in a field. He was on active service with the IRA and it blew up in his face, he was 16 or 17 years of age. The second young man was killed in the raid on the police barracks in Loughall, and the third son was killed when masked men broke into their shop and mowed him down as well as some customers and a cousin. So she’s left with a daughter who is her family now. I watched her and saw the incredible dignity with which she was able to speak not just about her children and those events but her life and the family she’d come from, an old republican family who for generations had been involved in the Irish nationalist struggle. It was nothing new for her to be among the disenfranchised. Her father and grandfather had been there, and her expectation was that this war would go on until the goal of getting Britain completely out of Ireland was achieved. And she didn’t say this bitterly, she knew what the stakes were — she described to me the day her son — he was 18 — came into the kitchen and said, “Mammy, I’m going out to fight, I’m going out to join the lads.”

She said to him, “Well, I understand, but you’ll never have a happy day as long as you live.” She understood and gave him the dignity of making his own choice. She would support him politically but she also knew the incredible stakes, the risk that most likely, even if he lived through it, he would never live a happy day, that it would always be a life of chasing a goal that he might not achieve in his lifetime and that he’d be shunned for doing so except by a small group of people. To know that’s the fate your child has chosen must be such a heartache, and that she could so describe it left me in awe.

Do you see this movie as being some kind of a defining moment in your life?

I do, actually. It’s the coming together of a lot of things, the experience of living for the last few years with my granddaughter her name is Kalina — combined with the role, being with Jim Sheridan and Terry George — he entrusted me with Annie. It’s been said about me that I fought for the part. I did, because I felt very strongly that I wanted to be entrusted with her and I felt somehow that I had to fight for that, to show them that I was the right person, that they could feel safe in giving me Annie to portray, that I would not shame her or diminish either her political authority or her personal authority and that I would play her with integrity.

When did you first get the script?

It’s so much better told by Terry — I think it’s become his party piece! They sent me the script via Michelle Burke, who’s the makeup artist, because she happened to have her studio not very far from where I live in California and Michelle came up to the house with the script and of course I perceived immediately that to send a three-time Academy Award winner as a postmistress with a script that there had to be something else afoot. I was enraged over that, so Terry and I had our first conversation on the telephone as a colossal fight, and then our second conversation as another colossal fight. Maybe that was just as well because we got our fight out into the open, up front, so we could skirt each other then throughout the shooting of the film as two fighters circling each other when it came down to discussing anything about the character. And maybe that was as well because it was a quality, although I wasn’t thinking about it at the time but he was, that you certainly needed in Annie.

It was certainly Annie Higgins as she marched into the mother superior to protest her daughter’s treatment.

Yes, and I’m actually one of the few people I know who had a very good experience with nuns. I was at the Dominican Scoil Caitriona in Dublin for my last few years at school and they were fabulous women, absolutely wonderful and they were so smart too. When they found out that I was interested in the theater and was spending all my evenings at rehearsals with amateur groups in Dublin they were terrified that I would fail my exams, so as a way to get me hooked into spending more time in school they founded a theater company in the school and they put me in charge of it. Very smart.

What were your parents like?

I think they were extraordinary. They understood that there was a broader world outside the corporation housing scheme where we grew up and they wanted us — all five of us — to have access to that world: the theater, and cinema and books — they read voraciously — and the Irish language. They sent us all to Irish speaking schools, and I’m so grateful they did because it did give me a key into an awareness of a nationhood to which I was entitled to claim membership. Even if I never spoke the language, even if I never exercised it on a daily basis, I did have access to the literature.

My father was old IRA. He was also a Communist who fought in Spain in the international brigade — one of those men who never got over the fact that Franco won. My mother is very ill now and to my great sadness hardly recognizes me. She recognizes the cadence of my voice but otherwise she’s sort of gone from us, you know, it’s that awful mist of dementia or Alzheimer’s or whatever they call it these days, of old age, and drifting away.

You wrote a beautiful essay on the Irish language and your parents.

I think that piece was my way of saying goodbye to both of them and the great legacy they gave me and their belief in the possibility of nationhood for Ireland. They had a great sense of justice and injustice and I think my mother had more courage in speaking out than I have ever had. She always spoke out when she felt something was unjust, and she didn’t care if she was accepted or unaccepted in the community.

My father would latch on to impossible schemes. I remember him going to the GPO one night with his last ten shillings, actually, my mother’s last ten shillings, so he could send a telegram — this was after the Nasser coup — to some Egyptian army man he had met saying, “We are in solidarity with you.” It was signed “the secretary of the Irish Egyptian Friendship Society.” My mother said, “What is the I/E Friendship Society?” and he said, “We are.”

Did you go directly into acting after school?

No. I wanted to, but my parents wanted me to have something to fall back on, even though I assured them I wasn’t going to fall back. The Abbey school had closed down for a long time and when it reopened I auditioned and was accepted. I trained under Frank Dermody, who is now dead, and Ernest Blythe was the artistic director. The theater itself was in the old Queens Theatre.

I was in a class with Des Keough, Donal McCann, Clive Gerrity and Eileen Lemass who then left and later went into politics — and John Lynch who was thrown out by Dermody and became a director and a producer in RTE. At the time I protested John being thrown out and then Dermody threw me out.

I was shattered, and then one day in the street, I was a schoolteacher at Marino technical school at the time, I ran across Thomás McAnna who was doing this play up at the Darner Hall called An Trial (The Trial) written by a woman who wrote Irish grammar books, and he wanted me to be part of it. And so I went and took part and when Cáitlín Maude, who was playing the lead got ill, I took over and that’s what brought me to the attention of Irish television and the English language stage. Phyllis Ryan decided to do the play in English and I played that role, and then I did it for television in Irish and got the Jacobs award that year. So roles began to tumble at me both in Irish and English television.

What was An Trial about?

It was an old story, based on truth, of a young village girl who has an affair with the local schoolmaster whose wife is a cripple. She gets pregnant by him and is thrown out by her family. She goes to Dublin, finds work with a family who find out that she’s pregnant and throw her out on the street. She then finds the prostitute with the heart of gold who takes her in. Then, eventually she gives birth to the child in a convent run by nuns who put it up for adoption — all of this is coming out now — but this is a girl who refuses to give her child up and goes the Madame Butterfly mute because she meets the man again and thinks he has come to Dublin to find her, but he hasn’t, and her heart is broken when she finds out that his wife has died and he has remarried. All her young, girlish dreams are shattered and so she takes the life of her child and herself.

Thomas directed it so that it was presented in a Brechtian way of who was at fault — the girl or society itself, and it was held like a trial. It was a new kind of theater in Dublin, very stark and the brilliance of it was that even people who only spoke the cupla focal, the few words of Irish, could understand it, and so it was an enormous hit.

Cáitlín Maude, a schoolteacher like me, had a nervous breakdown and eventually committed suicide, and so there was a horrendous legacy of tragedy that was contained in the cup of this play that started my career and ended the career of a fine poet.

I then went to work in English and Irish television and I worked at the Old Vic in Bristol. I played Pegeen Mike in Playboy of the Western World and I did Taming of the Shrew and I did the Friel play Lovers which Hilton Edwards directed at the Gate. I came to America with that and I stayed.

Why did you decide to stay?

I was fascinated. I also was running away. I had been married in Ireland and the marriage had broken up and I didn’t want to go back. I felt that I had failed as a wife — failed as a married woman — at my first go at it, you know. I got a lot of hate mail, believe it or not, anonymously written, of course, it followed me around as I toured with Lovers. People were willing to reproach me for not being the wife that I ought to be, whatever that was, and so I stayed here for quite some time.

I began to go back to Ireland when invited to do work. My friend Caroline Fitzgerald, a fine director, invited me back to do Happy Days for the Beckett Festival, and she also directed me in Summerhouse, and I was invited back to do Streetcar, although that was not a happy experience. So I like that they think of me and invite me back. I feel lucky because sometimes when you go away that’s it — you’ve committed the ultimate sin.

It seems we’ve gotten to a point where we’re starting to emerge a little bit.

Yes, I think that’s true and I think the X-case [14-year-old pregnant by father’s friend -parents sought abortion in England] helped because suddenly you had flushed out into the open this horrendous case involving the young girl, and the whole question of abuse to women and abuse to children began to become more public. It at least gave permission to some people to come forward and tell their stories and be able to unload some of the shame they’ve held for so many years. I remember Gay Byrne’s radio show a few years ago when he read on a daily basis the letters women wrote about having had abortions. I thought it was wonderful to allow those voices to come over the airwaves so the women could feel they didn’t have to hoard the secret any longer and suffer the pain of it and I thought it was courageous of him to do that.

I hope I don’t sound like I’m condemning Irish institutions, faulting them for not being courageous, but I still worry very much about the degree to which eyes are cast to England and on London for ratification for what is best and what is the standard and maybe that will become less so. I hope so.

Has it changed for women in Ireland? Is the younger generation different?

I hope that it has changed. At the same time, I went to see the movie The Snapper and there was a scene where the young girl who is pregnant goes to meet with her friends in a bar, and they are sitting around drinking and smoking — I watched that scene and there was something dreadful about it. I thought that’s not a true picture, and yet, it is, because I’ve seen the young girls sitting around the bars in Dublin and it’s pretty terrifying because there’s an enormous amount of smoking and self-destruction of a kind that’s appalling in these young women. It makes me very sad, and I wish they wouldn’t and I wish there was a consciousness. I wish there was a campaign in Ireland against AIDS.

One of the great things about the U.S. is the campaign that has been going on against AIDS: education, awareness, news coverage. Why don’t we have that in Ireland?

People think we are such great talkers but there is so much silence in Ireland about certain issues.

There is. The talk covers up the silence about the things that really matter: the self-destruction. Ireland has the highest incidence of AIDS in new-born babies of any country in Europe. Instead of billboards advertising liquor, why not have billboards warning people to be careful, making condoms available and making sex education and AIDS education available?

It’s still a Catholic state for a Catholic people. Sex education, condoms — that sort of thing is relatively new.

Yes, but it’s amazing the number of young people who say to me that they don’t pay any attention to what the Catholic church is saying. That doesn’t safeguard them from some of the things the church has chosen to neglect or to be silent about to prevent itself going against its own rules. Things like that worry me very much. This is like another genocide. Of course, there is a whole school of thought that regards the Irish Famine as genocide, and there are arguments that can be legitimately made for that under the United Nations Charter, and it’s only now beginning to be examined. There’s a genocide that we are perpetrating on ourselves in refusing to acknowledge that.

Do you think that all these past atrocities such as the Famine have left us a damaged people — have left us where we are inflicting our own wounds?

I do. My husband, Garret O’Connor, has written extensively about this — about the inherited legacy of colonialism which includes this internalization of shame and the inability to deal with it so we just pass it on to the next generation. There is plenty of proof of this in children who have been damaged and abused, and he has written now of extrapolating that into the larger nation. I certainly think he has a point there, and there are some people who are beginning to pay attention to that. I think poets and artists have always been aware of that but never in the sociological sense and never in the way of being able to come up with some kinds of solutions to stop it happening, to address it in our lifetime, and he has come up with that. It has met resistance because just as in alcoholism one of the first symptoms is denial, so with this kind of self-abuse or self-destruction one of the first symptoms is a reluctance to even entertain talking about it — the symptom of silence.

You yourself made a stand in your community in Hollywood by having a party for Sinn Féin’s Gerry Adams.

We’ve had parties for many people and try to be available to reach out for emissaries from Ireland of all sorts. Because we wanted to always allow our neighbors to have access to come and hear someone speak about issues that they maybe don’t even get to read about. We’ve had various people from various causes and we will continue to do so. We welcomed Gerry Adams because we felt that it was a time that was so critical, and it was an extraordinary act of courage on the part of the IRA and on the part of the loyalists who laid down their arms following the IRA cease fire. We had the opportunity and felt we were obliged as Irish citizens and as Irish people concerned about peace in Northern Ireland to do whatever we could to help that voice be heard. So we were only too pleased to have Gerry come to the house and talk to people, and it so happened it was his birthday.

Many of the papers phoned and wanted to come, and his express wish was that it not be a public event but a private party so I said no to the papers. But the London Sunday Times found the house and they parked outside the gate all night. Being California, the weather was fine and so a party takes place outdoors as much as it does in, and people were on the patio. A waiter dropped a tray of glasses. Of course, they didn’t see that but they heard it – they heard glasses crashing to the ground and that was written up as “Glasses were smashed and rebel songs were sung.” The inference always being that it was drunken Irish who couldn’t control themselves, couldn’t behave. Yes, songs were sung. Why not? We’ve written some of the best songs in the world, why shouldn’t they be sung? But I thought how subtly they put it, as if to indict us for celebrating the fact that we had an opportunity for peace and were offering the British government an opportunity for peace, which, of course, in hindsight we know they didn’t take advantage of. That’s why we felt delighted and privileged to host Gerry Adams.

There are probably people in Ireland who would think you were a rabid republican for doing just that.

Oh, I’m sure there are. It’s no longer politically correct, seemingly, to speak about feelings of nationhood or wanting to look at your country and look upon some of the wrongs that need to be righted and some of the desires we might have for complete freedom or a united Ireland. Why should that be such an extraordinary thing? It’s a very desirable thing, I think. But because that’s so politically incorrect in modem Ireland, to voice it you’re immediately branded as a rip-roaring, rabble-rousing, bomb-throwing person, a terrorist. We have been so brainwashed that people are now forced to talk about Ireland in terms of four green fields, so the whole canon of Irish literature with its wonderful laments is going to be consigned to some politically undesirable ash heap because we will be afraid that we will be branded as unfashionable, not Eurocentric, and politically incorrect.

I see it in little things on the street. If you say something in Irish people automatically assume that you’re a republican. They automatically attribute to you all of the horrors they attribute to republicans, and that to me is very dangerous. The revisionist historians have done their bit to politicize people too.

Yet there’s this whole creative thing going on in music and the arts. Riverdance for instance.

Yes. The music in Riverdance so wonderfully grew out of the modem influences of jazz, pop and rock upon an ancient art form, and the musicians, Eileen Ivers, of whom I am a huge admirer, and Davy Spillane, what they’ve done by taking old Irish music and modem music and what they’ve come up with takes my breath away.

Bill Whelan also did the score for Some Mother’s Son.

Bill Whelan’s marvelous score for our film is haunting, and I think is used beautifully. The creativity surrounding those art forms and the influence that the young people in Ireland have brought from Europe and from here to bear upon what they already had, traditional music, traditional stories, is great.

How do you see the whole Irish American dimension — do you think it’s important?

I do, very much so, and I would never have said that when I first came here. Maybe it’s here in the U.S. that we find a healing, for in the broader melting pot we get to look at some of these self-destructive attributes that we bring to bear upon our own quarrels and begin to solve them in ways other than just splitting apart. Especially if we are to have peace in the North.

What’s next, directing, producing, acting?

Well, I love directing, and I co-produce with my partner Catherine MacNeal. We produced Away Alone, the play about the young Irish in the Bronx. I directed it in Los Angeles in 1992 and at its European premiere in Dublin in the same year. We did it in order to raise consciousness about the young Irish illegal immigrants who were now beginning to filter west from New York and Boston and into our community. For most Americans to find an Irish person on their street is as natural as finding one from Iowa, so strong is the Irish American connection, but I wanted to make our community in Los Angeles aware of their plight, such as no work permits, fear of the police, fear of going to a hospital, fear of looking for a drivers license, et cetera.

What about writing? I recently read three beautiful essays that you wrote for Cercanías Distantes (Distant Relations).

I have to write something down. I flee away from that. I have four thousand books in my house, I know because they all fell down in the earthquake and I counted them! and every time I get a new book I know it’s a defense against writing something — they are a defense against putting down on paper that which I might want to say. These are pieces that I started to do on my mother and cultural identity, and somewhat to my astonishment people want to read that or enjoy it — but I’m glad they do. I’m so in awe of the pantheon of Irish writers — Eavan Boland just leaves me breathless when I read her poems — and thank goodness for the playwrights we have, the poets, Heaney’s work is extraordinary — and Edna O’Brien’s marvelous range of prose that’s been tamed to address us and free the same thoughts and emotions in our soul — what a girl to have. I look at those people as monks sitting in their little rooms writing away and enjoying, I’m sure, the torture of the damned as they wrestle with the words to bring them out. And I think I’m afraid of going into that room but I know that there is great joy there too and great freedom, so it’s true that I’d like to be able to tussle with the pen. So I suppose my turn is coming up.

Perhaps you’ll bring it to the screen?

Oh, that would be wonderful!

You have a sense then of where you’re going?

I’m only beginning to get a sense of who Fionnula Flanagan is in the last few years. I think that’s by virtue of having turned 50. I’ve seen incredible things in my time, yet as I grow older the things in everyday life — the tiniest cruelties, or acts of kindness — I now perceive as being mammoth. I think this is because of my step-granddaughter coming into my life. Kalina is 11 and I’ve been mothering her because her own mother died when she was five, and that has focused my attention on how enormously the smallest acts of kindness matter in the growing of a person. I see the changes in her face as she encounters these moments in her life, and I think, my God, it was the same when I too was a child, that those tiny little things on a daily basis mattered.

Editor’s Note: This article was originally published in the January/February 1997 issue of Irish America. ⬥

Thanks so very much for this worthy full interview, Learned wonderful things I did, Luv Irish women, my mum was O’Broyles

Todd

In

Toronto