Sean McGarvey began his career as a glazier, so it’s fitting that he has an office with a view. And what a view! McGarvey, president of North America’s Building Trades Unions (NABTU), has an unobstructed view of the White House from his office in the union’s headquarters on 16th Street in Washington, D.C. Not bad for a guy who was fresh out of high school when he began his apprenticeship in Philadelphia with the glaziers’ local union 252, in 1981. You could argue that McGarvey’s journey to lead a three million-strong union began in infancy when he was a two-year-old and his father, a teamster, moved his family to Northeast Philadelphia, a blue-collar neighborhood, filled with cops, firemen, teachers, constructions workers, factory workers, and tradespeople. Many of their new neighbors had Irish connections, and most of them were in a union. “When we first moved to northeast Philly, my parents didn’t know anyone other than the McCabes, the family who sold us our new home,” he says. Mr. McCabe offered to help the McGarveys settle into the neighborhood and introduced his three teenagers as potential babysitters for Sean and his four-year-old sister, Tricia.

The middle McCabe daughter, Jerry, became young Sean’s babysitter, and that connection would play an important part in his life going forward. Jerry and her future husband put him on the path to being a union man, a critical identity of his life. “The union was your most expedited ticket to the middle class, and people strived for that,” McGarvey said of the ethos of community he grew up in. It all started on a snowy day on McGarvey’s first winter out of high school, “I ran into Mr. McCabe in the neighborhood diner and he asked me what I was doing. I told him I was installing aluminum siding, but that I wasn’t working that day because of the weather. And he said, ‘Hey, my son-in-law is running the glaziers’ union now, you should think about becoming a glazier. I’ll connect you with Jim.’” McCabe’s son-in-law was Jim Williams, married to Jerry McCabe, Sean’s former babysitter and the coach of his former little league baseball team. “Long story short,” McGarvey says, “I took the test, had the interview, got accepted into an apprenticeship, and started on June 1, 1981.”

Patricia and his daughter Kelsey.

“So your babysitter opened a window for you,” I suggested, and drew a hint of a smile from McGarvey. “Absolutely. A good one.” McGarvey is a big man. At six-foot-two with a shaved head because he doesn’t have the patience to deal with his hair, he gives off a rugged, tough edge. He puts one in mind of a linebacker ready to jump to the defense of his players, his members, but as we settle into our conversation, his demeanor softens – less linebacker, more union cheerleader. Did you like being a glazier “I loved being a glazier. When my career began, it was during a time of transition as the greatest generation was starting to retire. I was working with a lot of World War II vets. As a student of history, I found their stories fascinating: where they were and what they did. It was just unbelievable. Back then, I worked with Kenny Fetters, who was a tank commander in Patton’s army. I worked with ‘Old Man’ Blineberry, who was on the Bataan Death March, and I worked with Snuffy Smith, the Santa Claus at our local union with his full white beard. He was a paratrooper who landed behind enemy lines on D-Day.”

Working with these veterans when he first joined the union was a great experience for McGarvey. “This cast of characters are all gone now, but they had, as I have always been amazed by, ‘seen it all, done at all, killed it all, and watched it all be killed’ when they were 18, 19, 20 years old. That was for their country; when they came home, it was about their community, their union, their church and – most importantly – their family. They literally built their way into the middle class.” McGarvey began making upward strides to the middle class in the union almost right away. “I had some acumen and worked hard. Jim Williams encouraged me along the way to participate and volunteer: all the things that you need to do to make a successful local union.” Williams urged McGarvey to run for office in 1985, “So I became recording secretary. I did that until 1994, when I was elected business agent.”

Moving on Up!

So began his rise to the top. Ed Sullivan retired from NABTU in 2008, and Mark Ayers became the NABTU president for the next four years. When Mark died suddenly in 2012, McGarvey succeeded him as president. “That’s how I got here,” McGarvey says. “Somebody helped me and looked out for me every step along the way. A lot of it I did on my own. I got up in the morning, did my work, was thoughtful, and worked hard. But nobody gets anywhere in this world without people helping them.” As the leader of NABTU, which has 14 building trade unions under its aegis, McGarvey always sticks to his modus operandi, which is – borrowing from his own life story – “to focus on helping workers get to the middle class through the construction trades, and the membership always comes first.” He’s also making diversity central to the union’s mission, which means more inclusion of underserved communities: women, people of color, veterans, and the formerly incarcerated.

Asked how the union is different now from over five decades ago, he says: “We have a keen focus on recruiting at-risk communities, minorities, women, and veterans, so I would say we are much more diversified now. Second, there’s a cultural change – we now see the owner as a customer and client, not an adversary. We’re in sales, and what we sell is skilled manpower – the finest, safest construction craft workforce in the world. It’s good. These rightful changes are why we continue to grow and have gained over 400,000 new members in the last six years.” Helmets to HardHats Impressed by the veterans who inspired his pathway, President McGarvey was keen to expand the Helmets to Hardhats (H2H) program put together by Ed Sullivan. “When soldiers were first coming back from Iraq and Afghanistan, we had an extraordinarily high number of veterans unemployed. Ed connected with Matthew Caulfield, a major general retired from the Marine Corps, and they came up with the idea to start a program that would help transitioning military personnel, either active duty or guard and reserve, get into registered apprenticeship programs and into our trades. For the past seventeen years, we’ve helped over thirty-six thousand service men and women get into the trades. Not only have they gone through apprenticeship, many are journey-level status now and at various levels of leadership in their unions.”

“It’s some of the most rewarding work we do,” McGarvey says. War stories aside, he respects the discipline armed servicemen and women bring to the job. “We’re talking about a group of people who have all the soft skills, know how to work as a team, and how to take orders. They get up in the morning, and get the work done on time to the best of their ability – all of the things you need in the construction industry, and on a construction site. It’s been great for them, it’s been great for us, and it’s been great for our contractors, clients, and the construction users that we serve. We’re happy that almost everybody in the country does it now, but our program was way ahead of the curve.” McGarvey is proud of many aspects of his job, but feels the best thing (perhaps because it echoes his experience) are the apprenticeship programs. “When you take somebody from a community that hasn’t had a lot of opportunity over a couple of generations, and you help flatten the road a little bit for them, and they make it: that is what it’s all about. The satisfaction that you get from that “thank you” letter or card saying how important it was for them, or their family, to get into the program – and then, to see them succeed – is the most rewarding thing.” NABTU assists in setting up these programs by developing curricula, training trainers, and supporting programs at large, but they are managed regionally across the United States and Canada. For instance, in New York City, the program operates out of the Eddie Malloy Center.

Focused on the Future

In addition to Helmets to Hardhats, NABTU works with Urban League, Youth Build, different church and community groups, education and school counselor associations, major corporations like Southern Company, and executives like Alabama Power’s Mark Crosswhite, and Jamie Dimon from J.P. Morgan, who help support apprenticeship readiness programs that usually last six to eight weeks. “ARPs are like an introduction to the trades. We introduce them to blueprint reading, applied STEM, health and safety, and then get them ready to take registered apprenticeship tests. Our registered apprenticeship programs, all over the US. and Canada, commit to taking as many of the successful candidates as they can, and then they’re either in a three or five-year apprenticeship program. It’s phenomenal.”

Bringing it all back home

Just as Uncle Pete took in his father and the McGarvey kids, his great-grandmother, Annie Heaney, raised his mother. “Annie grew up in Limavady, a townland in County Derry where her father was the local cobbler. They were Catholics. They knew their situation in the North was not good. A bitter civil war was raging over the partition of Ireland, and they were in British-occupied County Derry. Annie asked her parents if she could go to America, and they reluctantly agreed. “Friends and families scraped together fifty dollars, and twenty-year-old Annie got on a boat with an overcoat and a suitcase,” he says. Landing in Boston, the cobbler’s daughter found work in a shoe factory. A few years later, she moved to Philadelphia, where she met Frank Donaghey, another immigrant from Northern Ireland, County Tyrone. They met at St. Veronica’s church, fell in love, got married, and had six children – their Irish-American family.

Annie maintained a positive disposition about her new country, but her husband Frank was difficult to be around. McGarvey recalls this from his mother’s testimony: “He was bitter, and angry, and never got over the discrimination he experienced early in life.”

A Second Chance

Getting the opportunity to be introduced to the trades is one thing, but McGarvey says there are still other stumbling blocks that underserved communities face, in particular the formerly incarcerated. “The requirements to get on federal reservation sites, such as an Air Force base or a federal office building – construction workers with a felony conviction couldn’t get on them.” McGarvey and his team “contributed our experience” to the Trump administration on the issue. “We met with policymakers multiple times to talk about our programs, and how we do it.” Most recently, McGarvey was very pleased to see the First Step Act passed to change the law on employing the formerly incarcerated. Giving people a second chance is something that McGarvey is big on. “My dad spent a little time in reform school. But he turned out to be a phenomenal father, and a phenomenal husband. You know, just a great guy. He was a teamster and worked two jobs, most of the time.”McGarvey’s still trying to piece together the hardscrabble story of his father’s early life. He knows that his grandfather on the McGarvey side lost three wives in childbirth, and that when he lost the last one, he was unable to focus on his children. “After he couldn’t take care of the family, the four youngest – including my father – were all split up. My dad lived with a series of different families in different neighborhoods for a good six years.” “My dad had an older stepbrother, Uncle Pete, who got out of the Navy at 20, got married, and had a small apartment. He and his young bride went and gathered up all of the kids and brought them home. At that time, my dad and his siblings were around twelve, thirteen, and fourteen years old.” McGarvey’s sister Colleen, who is working on their father’s story, came across a newspaper article about seven-year-old Jack McGarvey being hit by a trolley car. Considering other life-altering incidences, she says she doesn’t know how their father survived his early life.

While Annie’s economic situation hadn’t advanced much, she wanted her children to have a better life and more opportunity in America. When the war came, and her boys were able-bodied, she took them down to send them off to fight for her country. And then she prayed for their return. McGarvey says, “Every night, around five o’clock, a military staff car would start driving through the neighborhood and all of the women would stand on their porches and hope that car didn’t stop at their house. None of them wanted a letter from the president thanking them for the sacrifice of their son, or a gold star to put in their window.” Patrick Donaghey, Annie’s oldest son, was 32 years old when he joined up. As a union sign painter, he became a Seabee in the Navy’s construction battalion. The Seabees fought alongside the U.S. Marines across the South Pacific. To Patrick, it was an adventure. “He was the only person I ever talked to who thought that the war was a wonderful experience. He used to say, ‘The places I went, and the people I met there… If it wasn’t for the war, I would never have seen the Pacific.”

Sadly, while Patrick was away in the South Pacific, his wife dropped out of sight, and his baby daughter, Patricia, wound up in an orphanage. No one knew where the young girl was. It wasn’t until 1945 that her grandmother, Annie Heaney, finally found her and brought her home.“My mother was exceedingly close to her grandmother,” McGarvey says. Even today, she speaks of her with reverence and awe. And the love was reciprocated. Annie would fill the young girl’s head with stories of growing up in Limavady and share with her the letters from home.“The amazing part to me, given the world we live in today, is that when Annie got on that boat, she never saw or spoke to her parents again. But throughout her life, they had beautiful correspondence back and forth, and lots of letters were written. We’re grateful that those survived. My mother saved all that stuff.”

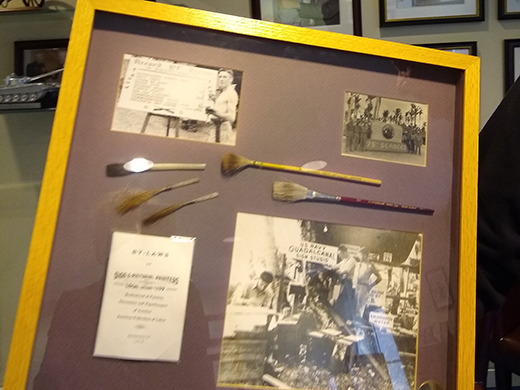

Other mementos survived as well. “He loved having his photograph taken,” McGarvey says, showing me a shadow box of mementos from his grandfather’s travels that he keeps in his office. All of Annie’s sons came home from the war; they all got union jobs, and they never left home again. When Annie died in 1968, she had three sons and a daughter, who still lived with her.

A Visit to limavady

In 2016, McGarvey decided it was time to take his mother “home.” It was the 100th anniversary of the Easter Rising, and there was a big contingent of North American labor going over for the groundbreaking for the Conno-lly Center in Belfast (James Connolly, one of the leaders of the Rising, had American labor connections). “I took my youngest daughter and my mom and dad. We hired a car and driver and went to Derry. We found St. Patrick’s parish in Limavady. We didn’t know anyone there, but we found the church and snapped gravestone pictures of all the Heaneys and Donagheys. My mom wanted to talk to the priest, but he was in another town doing a funeral. Some lady randomly drove up outside the parish, and my mom got to talking to her, telling her she’d been hoping to talk to the priest. And the lady said, ‘Oh, there’s a woman who lives three doors down who knows everything about everybody. Do you want me to ask her if she’ll see you?’ Within a couple minutes, the lady was back, and long story short, we got in our van, drove down to the house and went in. There were three women there, and two of them were my mom’s second cousins. “My mom’s grandmother and their grandmother were sisters. These ladies had books of photographs and connected an unbelievable amount of dots for my mother about our extended family. “My mother was so thrilled. She told me her life is complete now that she made this connection. My mom doesn’t do email, but my daughter stayed in touch with one of these women. About three months after our trip, she sent my mom a painting of the house where my great-grandmother was born, under Thieves’ Hill. It had been painted by a nun around 1928.”

The View from the Top

McGarvey’s office is lined with photographs and memorabilia; casual snapshots of his parents, his children, step-children, grandchildren, and his wife, Shari, line the walls and the window sill, framing its view of the White House.Mixed in with the family photographs are pictures of McGarvey with political heavyweights, including Presidents Clinton, Obama, and Trump. There is one of him and Hillary – “A good woman” he respected like no other – whom he bled for trying to get her elected, and wept for when she didn’t make it. His beloved French bulldogs Gomers and Meany sit on his desk, which is his most prized possession as a union leader because it was Geroge Meaney’s desk.He claims to be bipartisan as a registered Independent, after many years as a Democrat. “I believe that there’s probably ten percent of right-wing Republicans who believe it and live it. There’s ten percent of ultra-liberal Democrats who believe it and live it. And then there’s that eighty percent in the middle who are moderate, who, I believe, if not for the politics, would work together across the aisle for the betterment of the nation.”McGarvey keeps his most important keepsakes in a drawer in his desk. These are letters from people saying how being accepted into the union’s apprenticeship program changed their lives. There is one from Dawn Benitez, a woman from Waynesboro County, Georgia, who was a former staff sergeant with the U.S. Army.

Dawn served with distinction, earning an Iraq Campaign Medal with a Campaign Star.

influencers of the day, including Presidents Obama and Trump, former First Lady Hillary Clinton, and family photographs and memorabilia, including this shadow box of mementos of his grandfather’s time in the Navy in WWII.

“I talk about Dawn a lot,” he says. “After her service to our nation, like too many veterans, she struggled to find meaningful employment. She was homeless and she and her daughter lived in her car. Through our apprenticeship readiness program in conjunction with Southern Company, she went to work in the ironworkers’ union as a registered apprentice. Now, she has been in the business for about eight years. She is completely self-sufficient and a phenomenal iron worker. The woman’s story would crush you because that opportunity changed her world.” “There are thousands of stories like that. When I have the bad days that we have in this business, and want to pull my hair out or go get a stiff drink, I keep letters and stories like hers in my drawer. Many times, I just pop one of them out to read at the end of the day. I remind myself that our focus is to create ladders of opportunity to help people get to the middle class through registered apprenticeship and unionized construction trades. That’s really why we do it.”

Sean McGarvey has a bachelor’s degree in business administration and is a graduate of Harvard University’s Trade Union Program. Married to his lovely wife, Shari, Sean has two daughters, two step-daughters, and two grandchildren named Lucas and Leah.

Excellent article, Patricia!

Bless Sean McGarvey!