Chris Matthews talks about his new book, which offers valuable insights into Bobby Kennedy, and why we need someone of Kennedy’s ilk today.

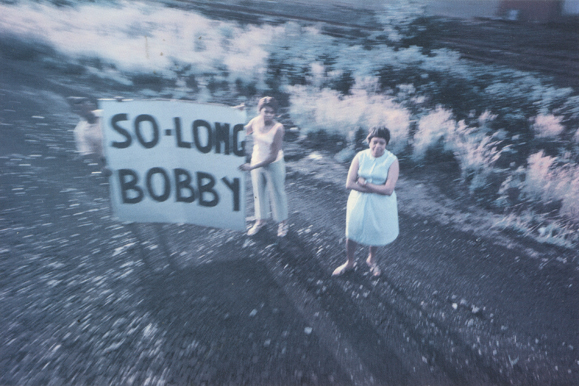

Next year, on St. Patrick’s Day, the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art will open a new exhibit entitled “The Train: RFK’s Last Journey.” The centerpiece of the show will be more than two dozen large color portraits taken by Look magazine photographer Paul Fusco, who was on board the train that carried Bobby Kennedy’s body from New York City to Washington, D.C., following the presidential candidate’s assassination on June 6, 1968.

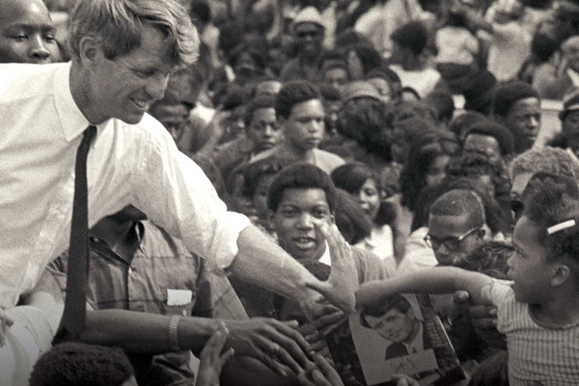

These stunning photos, in many ways, represent the way the martyred Kennedy has been remembered in the 50 years since his death. Fusco took over 1,000 photographs of people who came to watch the train pass. They were old and young, rich and poor, urban and rural, black and white.

And for those few months when Kennedy was running for president, many actually believed he was the one man who could bring together a country that seemed intent on tearing itself apart.

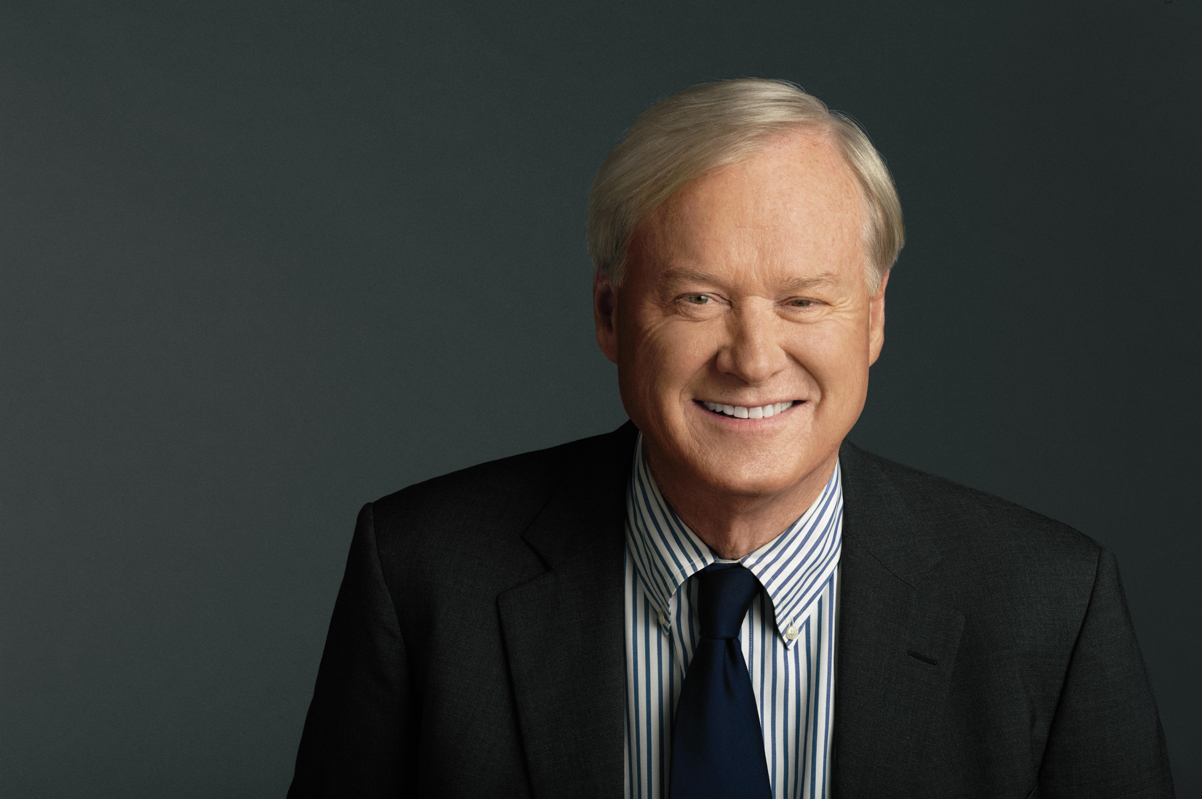

“Bobby Kennedy is the kind of leader we don’t have today,” political pundit Chris Matthews told Irish America during a recent phone interview, taking a break from preparations for that evening’s episode of his long-running and highly-rated MSNBC talk show Hardball with Chris Matthews.

“We don’t have a leader with empathy, who’ll fight for unity… we don’t have someone who’s a moral authority. [Bobby Kennedy’s] what we don’t have, he’s what we lack [and] he fits the needs of the country right now.”

Matthews, who grew up attending Catholic schools in an Irish American Philadelphia family, has just published a new book about RFK entitled Bobby Kennedy: A Raging Spirit.

The book, Matthews writes, “is about the Bobby Kennedy we’d want to have today.” Many readers seem to agree. On the day we spoke, right before Thanksgiving, the book was lodged at fourth on the New York Times best-seller list for non-fiction.

℘℘℘

In his book, Matthews quotes journalist Jack Newfield, who said Bobby Kennedy “felt the same empathy for white workingmen and women that he felt for blacks, Latinos, and Native Americans.”

Congressman John Lewis added, “People treated him like he was some rock star. It was young people. It was blacks, whites, Hispanic, just pulling for him.”

But Matthews doesn’t shy away from a full portrait of Kennedy, exploring his numerous shortcomings, among them his life-long affection for notorious Irish American commie hunter Senator Joseph McCarthy.

“Bobby was with [McCarthy] all the way – until he saw how Roy Cohn was ruining him,” Matthews said, referring to the aide who, like McCarthy, launched reckless charges and ruined lives during the desperate 1950s hunt for communists in the U.S. government.

Even after Kennedy left McCarthy’s staff and wrote the U.S. Senate resolution condemning McCarthy, he maintained (as Matthews put it), “a tremendous personal affection for McCarthy.”

In his book, Matthews relays the famous story of Bobby quietly attending McCarthy’s funeral.

In Matthews’ opinion, this illustrates one of Kennedy’s most distinctive traits.

“He was so loyal,” Matthews said. “Both Jack and Teddy always said what they honored most in their brother was his loyalty.”

℘℘℘

Bobby Kennedy: A Raging Spirit is Matthews’s eighth book about politics and history, most written in the 20 years since he has been hosting Hardball.

His parents were a “mixed-marriage” by mid-20th century standards. His mother, Theresa, came from a large Irish Catholic family, while his father was a Protestant (who converted) with roots in Antrim. Matthews attended Holy Cross College in Massachusetts and served in Africa in the Peace Corps, before moving on to Washington. His first job there, however, was not political. Matthews actually worked as a U.S. Capitol police officer. Soon enough, though, Matthews worked for several Democratic congressmen, and even mounted a run for a congressional seat outside of Philadelphia in 1974. (He lost.) Matthews then worked as a speechwriter for President Jimmy Carter, before moving on to his biggest political job, as Chief of Staff for legendary Boston Irish American Tip O’Neill, during O’Neill’s years as Speaker of the House. (This informed one of Matthews’ best books about two of Irish America’s most famous politicians, 2013’s Tip and Gipper: When Politics Worked.)

Without question, Matthews experiences as a political insider inform some of the best passages in Bobby Kennedy: A Raging Spirit.

Bobby hustling behind the scenes at the 1956 and 1960 Democratic conventions makes for great reading, and Matthews strikes a good balance by offering a view from inside the beltway, while also making sure the focus stays on the Kennedy clan, and not Matthews himself.

The book also offers valuable insight into Bobby’s youth. Always emotional, he “couldn’t help but reveal himself if circumstances evoked it,” Matthews writes. Kennedy even once wrote a letter to Boston’s Richard Cardinal Cushing, voicing complaints about a priest who argued that salvation could not be found outside the Catholic Church.

John F. Kennedy, who Matthews has also written two books about, often referred to his younger brother as “Black Robert,” and felt that Bobby was sometimes “too serious, too earnest, too much the straight arrow,” Matthews writes.

But, as Matthews also makes clear, it was those qualities – sprinkled with heaping doses of ruthlessness and ambition – that made Bobby an effective taskmaster for his more dashing brother.

“Jack was kind of a Brit, he was kind of an aristocrat,” Matthews said. “Bobby wasn’t trying to fit in with the country club types… he didn’t want to go off with the aristocrats like Jack did.”

This was also the result of Bobby trying to prove to his father, Joseph Sr., that he could be tough. The Kennedy patriarch lavished so much attention upon his older sons, Joe Jr. and Jack, that Bobby was often ignored, and made to feel weak.

“There was… a permanent scar left on him by his relationship with his father, which carried a personal experience of rejection,” writes Matthews, adding that Bobby “yearned for Joe’s attention and dreaded his disapproval.”

Perhaps most interestingly, Matthews writes that Bobby was the “least assimilated” of the Kennedy children.

As Matthews said, “He was really driven by family. He had an almost ferocious loyalty to the family. Which is very Irish.”

There’s also “no doubt,” Matthews said, “Bobby was the most religious of the Kennedy boys.”

Kennedy was also the most likely to draw on his family’s own immigrant past when looking at the problems America faced once he began serving in his own brother’s presidential administration.

“The Irish were not wanted when my grandfather arrived in Boston,” Bobby remarked following race riots in Montgomery, Alabama. “Now an Irish Catholic is president of the United States. There is no question about it – in the next 40 years, a Negro can achieve the same position my brother did.” (Kennedy, of course, actually wasn’t far off.)

As Matthews writes, “The most Irish of the Kennedy children… it wouldn’t be wrong to say [Bobby] was, despite being a third-generation American, the least changed from the old country.”

℘℘℘

(Simon & Schuster / 416 pp. / $28.99)

All of this combined to fuel Kennedy’s ambition, which often crossed the line into cut-throat ruthlessness. And yet, so much changed for Bobby – and for the country – on November 22, 1963, when his brother was assassinated in Dallas.

In the years that followed, Bobby’s sense of Irishness and Catholicism transformed. Now, according to Matthews, Bobby Kennedy identified with the downtrodden, and felt a Christian duty to help those in need.

By 1968, as the Vietnam War took a turn from bad to worse, some Democrats felt President Lyndon Johnson, who just four years earlier had been overwhelmingly reelected, needed to be challenged. Initially, Kennedy turned such overtures down. But after torturing over the decision, Bobby Kennedy belatedly entered the race for president in March of 1968. His main opponent was fellow anti-war candidate (and Irish Catholic) Minnesota senator Eugene McCarthy.

And for a few months – as the Vietnam war ground on, as racial tensions grew, and as Martin Luther King, Jr. was assassinated – McCarthy and Kennedy tried to persuade the American public there was still hope.

Kennedy won a major victory in the California primary on June 5, and told the ecstatic audience at the Ambassador Hotel afterwards: “I think we can end the divisions within the United States, whether it’s between blacks and whites, between the poor and the more affluent, or between age groups or on the war in Vietnam. We can start to work together. We are a great country, an unselfish country. I intend to make that my basis for running.”

As he left the hotel with his wife, Ethel, Bobby Kennedy was shot and killed by 24-year-old Sirhan Sirhan, a Palestinian activist, who cited Kennedy’s support for Israel as his motive.

Kennedy’s killer, now 73, remains imprisoned at the Richard J. Donovan Correctional Facility in San Diego.

“It was simply about loss,” writes Matthews, who was 22 at the time. “It’s what I felt as I watched the news footage of the Penn Central train, carrying him south from his funeral at New York’s St. Patrick’s Cathedral down through New Jersey, Delaware, and Maryland, to Washington’s Union Station. His presidential campaign had lasted eighty two days. ‘The Impossible Dream’ was Bobby’s song. He knew the odds against him. Conscience, not glory, was what had called Kennedy into service. Now his death left a void as large as his promise.”

Fifty years later, it is a void we still feel. ♦

We do have just such a man. His name is Robert Francis O’Rourke. Goes as “Beto.” He is a third-term Congressman from El Paso, Texas, running for the U.S. Senate to replace Ted Cruz. This young man is the promise of the future.

I worked for RFK during the spring of 1968. As a generation, we did well (Voting Rights Act, Civil Rights Act, Medicare, and more). But we failed in so many ways. It’s his generation’s turn now. Have a look:

https://www.vanityfair.com/news/2017/05/beto-orourke-ted-cruz-texas-senate-2018