The Battle of the Little Bighorn, the most significant engagement of the Great Sioux War of 1876, saw the defeat of General Armstrong Custer and his soldiers of the 7th Cavalry (many of them Irish) by a battalion of united Lakota, Northern Cheyenne, and Arapaho tribes.

Few people know the pain of being dispossessed of their land better than the Irish, but tragically in the 1870s, thousands of impoverished Irish immigrants ended up enlisting in American armies that were fighting to push Native Americans off their land.

Irishmen fought and died in the most iconic conflict between Native Americans and the United States Army at the Battle of the Little Bighorn in Montana. The defeat of the General Custer’s 7th Cavalry by Native Americans on June 25, 1876 has become legendary. Many people know the story of Custer’s defeat, but few are aware of the role the Irish played in fighting the battle, and in creating the most famous painting of it.

One hundred and three Irish soldiers perished on that fateful day, and yet another Irishman, John Mulvany, realizing the popularity a canvas of the battle would create, painted his iconic “Custer’s Last Rally,” which remains today one of the most celebrated paintings of the American West.

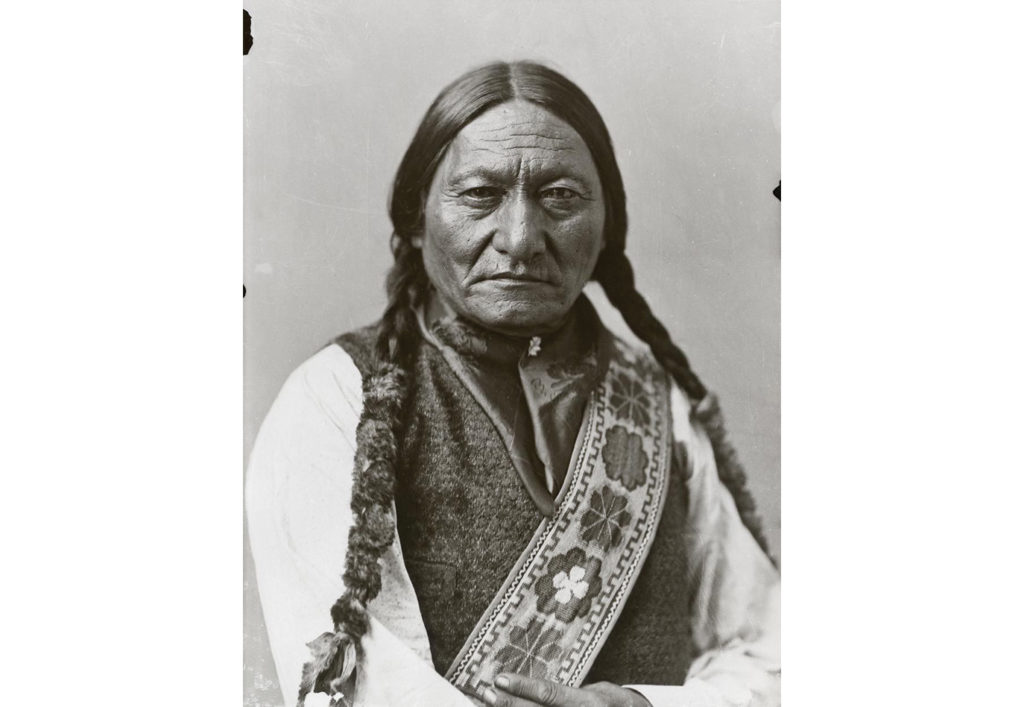

In the 1870s, the hard and dangerous life as a trooper in the American cavalry was still the best option for many poor, newly arrived Irish immigrants. In 1875, Custer’s 7th Cavalry was full of Irish immigrants when gold was discovered in the Black Hills of South Dakota, the sacred ground to the Lakota. The Irish soldiers must have known the danger they faced when the United States claimed the land and invaded it, despite treaties the American government had signed with the Lakota, guaranteeing them its ownership. The military’s armed incursion into the area led many Sioux and Cheyenne tribesmen to leave their reservations, joining the rebel leaders, Sitting Bull and Crazy Horse, in Montana. By the late spring of 1876, more than 10,000 Native Americans were camped along the Little Bighorn River – defying a War Department order to return to their reservations and setting the stage for the famous battle.

The charismatic General George Armstrong Custer and almost 600 troops of the 7th Cavalry rode into the Little Bighorn Valley, determined to attack the native encampments. Riding with Custer were over 100 Irishmen, ranging in rank from newly recruited troopers, many of whom could barely control their mounts, to Captain Myles Keough, a heroic veteran of the Civil War from County Carlow. There were 15 Irish sergeants and three Irish corporals in Custer’s command, the backbone of his noncommissioned officers.

Today, we picture General Custer wearing his trademark buckskin jacket – it was sewn by an Irishman, Sergeant Jeremiah Finley from Tipperary, the regiment’s tailor. The song of the 7th Cavalry was another Irish influence. Just prior to Custer’s arrival in Fort Riley, Kansas, where he took command of the 7th Cavalry, Custer ran into an Irish trooper who, “under the influence of spirits,” was singing “Garryowen,” an Irish song. Custer loved the melody and began to hum the catchy tune to himself. Custer made it the official song of the 7th Cavalry and it was the last song played before Custer and his men separated from General Terry’s column at the Powder River and rode off into history.

The battle, fought between the Jacobite and the Williamites forces in Aughrim, County Galway on July 12, 1691, it was one of the bloodiest battles in Ireland’s history, over 7,000 killed.

The battle marked the end of Jacobitism in Ireland, a movement that aimed to restore the Roman Catholic Stuart King James II of England and Ireland (as James VII in Scotland) to the throne. Photo: Gorry Gallery

Before the battle, the famed Lakota warrior Sitting Bull had a vision in which he saw many soldiers, “as thick as grasshoppers,” falling upside down into the Lakota camp, which his people saw as a foreshadowing of a major victory in which a large number of soldiers would be killed. Custer, however, blinded by ego and visions of glory, made a reckless decision to attack the huge gathering of Native Americans, saying, ironically, “Boys, hold your horses, there are plenty down there for us all.”

Foolishly splitting his command into three units, Custer tried in vain to attack and envelop the largest concentration of Native American fighters ever to face the American Army. The first assault against the Native American encampment was launched shortly after noon by three companies – 140 officers and men – led by Major Marcus Reno, whose men attacked along the valley floor towards the far end of the camp. Thrown back with many casualties, the survivors scrambled meekly for their lives to the top of a hill. Custer, with five companies totaling more than 200 men, advanced along the ridgeline, commanding the river valley on its eastern side. He further divided this force into two groups, one of them led by Captain Keogh.

There is debate about what occurred when Custer engaged the Native American forces just after 3 p.m. because the general and all his men were killed, so no one from Custer’s command could tell their tragic tale. Archaeological evidence suggests that Keogh and his men fought bravely, being killed while trying to reach Custer’s final position after the right wing collapsed.

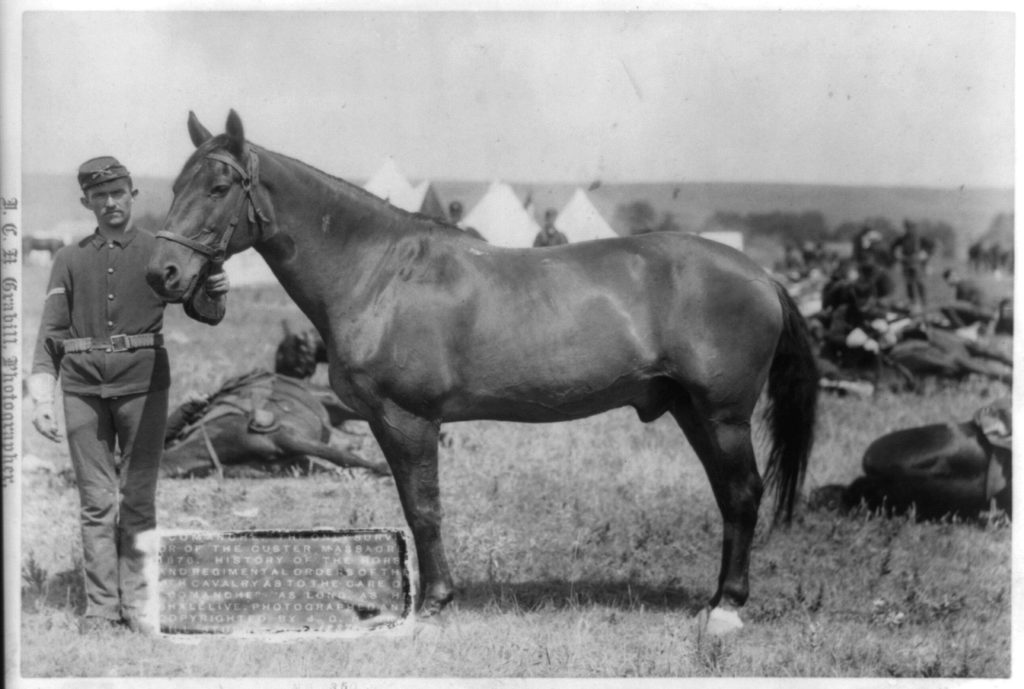

On June 27, 1876, members of Gen. Terry’s column reached the Little Bighorn battlefield and began identifying bodies. Keogh was found with a small group of his men and his was one of the few bodies that had not been mutilated, apparently owing to a papal or religious medal that he wore about his neck (Keough had once served in the in the Battalion of St. Patrick, Papal Army). Although Captain Keough did not survive the battle, his horse, Comanche, did. The horse, spared by the Native American fighters for its heroism, recovered from its serious wounds and was falsely honored as the lone survivor of the battle (many other U.S. Army horses also survived). Comanche was retired with honors by the United States Army and lived on another 15 years. When Comanche died he was stuffed, and to this day remains in a glass case at the University of Kansas.

Americans, shocked and angered by the defeat of Custer and his men, demanded retaliation. And they got it. Soon after, over a 1,000 U.S. troops under the leadership of General Ranald Mackenzie opened fire on a sleeping village of Cheyenne, killing many in the first few minutes. They burned all the Cheyenne’s winter food and slit the throats of their horses. The survivors, half naked, faced an 11-day walk north to Crazy Horse’s camp of Oglalas.

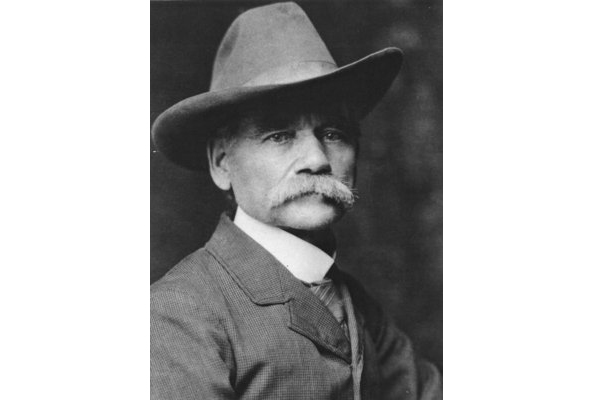

The victory at Little Big Horn marked the beginning of the end of the Native Americans’ ability to resist the U.S. government, but 37-year-old John Mulvany from County Meath saw opportunity in the tragedy.

Mulvany arrived in America as a 12-year-old. He went to art school in New York City and became an assistant of famed Civil War photographer Mathew Brady. He later covered the Civil War as a sketch artist for a Chicago newspaper, developing an amazing ability to capture battlefields on canvas.

Mulvany knew that a painting of the fight would be a sensation. He visited the battlefield twice and also found Sitting Bull in Canada so that his painting could capture the battle. Mulvany finished the epic 11 ft. x 20 ft. canvas in 1881, which was hailed as a masterpiece, and began a 17-year tour of the United States. The canvas made Mulvany the toast of Chicago, but his good fortune would not last.

Mulvany eventually sold his painting and ended up destitute in Brooklyn, where he drowned in the East River in 1909 in what many labeled a suicide. Mulvany quickly became forgotten, but not the fame of his great canvas, which recently sold for $25 million.

Sitting Bull would have more contact with the Irish. After the battle of the Little Bighorn, he became a star attraction in Buffalo Bill Cody’s Wild West Show. He gave away huge amounts of the money he earned from the show to the indigent and returned to the Standing Rock Reservation in 1881. In 1890, fearing that he was involved in planning another uprising, Indian Service agent James McLaughlin ordered his arrest. Sitting Bull was killed during the attempt. ♦

Hi and thanks for a great article! Just one observation – please look up the date of the Battle of Aughrim. 1691 I think. It proved to be more significant than the Battle of the Boyne in its effect on the ability of the anti Williamites to withstand the imposition of Williamite policies on Ireland.

This article has a number of errors, and among these is the notion that Gen. Custer was unfamiliar with the song “Garryowen” until after the Civil War.. However, it was a popular tune during that war and, if Custer’s tastes in reading while as a cadet at West Point have been accurately reported, would also have been mentioned a number of times in one of his favorite novels — Charles Lever’s 1841 CHARLES O’MALLEY, THE IRISH DRAGOON.