The setting, Transylvania. The writing style, High Victorian. The story’s appeal, universal. But the author of one of fiction’s most famous and imitated works is Irish. Carstens Smith brings us the story of Bram Stoker, the creator of Dracula.

Bram Stoker, whose name is less well known than that of his creation, Dracula, was born in Dublin on November 8, 1847. He was called after his father, Abraham Stoker, a Dublin Castle clerk. Though bookish and solitary as a child, he later became a successful athlete at Trinity College, where as a tall, broad-shouldered student with thick red hair and a beard, he was noted for his expansive, outgoing nature, and extreme chivalry.

After graduation, Stoker was an Irish civil servant for years before moving to London to work with Henry Irving. Prodigiously productive in diverse areas, he completed a law degree and wrote a tome to standardize Irish civil service procedures, The Duties of the Petty Sessions in Ireland, while immersed in the creative world of London theater.

Though he wrote Dracula along with 16 other novels (The Lair of the White Worm was the only one to come near the success of Dracula) while living among the most cosmopolitan elements in London, Stoker’s Gothic imagination had its roots in Ireland and in the stories told to him by his remarkable mother Charlotte.

For reasons never fully explained, Stoker spent the first seven years of his life bedridden. Charlotte schooled her son bedside and entertained him with traditional Irish tales of banshees, ghouls and hauntings, as well as vivid accounts of her own experiences as a young woman during the 1832 cholera outbreak in Ireland. At Stoker’s request, his mother wrote down her experiences, and her stories reflect a powerful gift for imagery, suspense, and building terror. Charlotte Stoker wrote of the epidemic, “Its bitter, strange kiss, and man’s want of experience or knowledge of its nature, or how best to resist its attacks, added, if anything could, to its horrors.”

A Stoker family story about Charlotte which she notably omitted from her own accounts of the epidemic took place during the last desperate weeks of the plague, when looters began pillaging homes throughout Sligo, the town in which she and her family lived. According to family history, Charlotte, upstairs in the locked and bolted home, saw a man trying to break in through a skylight. As the man’s hand came through the broken glass of the window, she grabbed an axe and swung hard, cutting off the intruder’s hand at the wrist.

The powerful woman who may, indeed, have cut off the hand of an intruder in order to protect her family was balanced by her husband, Abraham, a quiet man 20 years her senior who believed in hard work and honesty and a personal code of avoidance of office politics, which ensured that he had few promotions.

Though he struggled financially to support his wife and seven children, Abraham Stoker enriched his family through his enthusiasm for the arts, especially theater. During Bram’s college years (where he made up for his seven years of immobility by becoming a champion race walker), the elder Stoker and his son would often slip away to the Theater Royal’s cheap seats to catch a matinee performance. It was during this time that Stoker first saw Henry Irving and was impressed with the depth that Irving gave the stock role.

Several years later, Stoker, now an Irish civil servant himself, saw Irving again and was overwhelmed by the actor’s performance in The Two Roses. Incensed that the local paper did not review the play, Stoker contacted the Dublin Mail’s editor, Dr. Henry Maunsell, and offered to review it for free. Maunsell, quick to recognize a good deal, immediately made Stoker the unpaid, and, for the first five years, anonymous, reviewer for the paper.

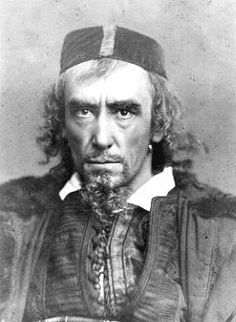

When Irving and Stoker actually met, the rapport was instantaneous and the two spent the evening and into the dawn passionately discussing theater and the arts. Like the editor of the Dublin Mail, Irving knew how to attract talent and give little compensation in return. He persuaded Stoker to become his stage and business manager.

For the next 27 years, Stoker devoted himself to promoting Irving’s career and and making Irving’s theater, the Lyceum, a viable business. In return, Irving compensated Stoker so poorly that during a period of illness following a stroke, he had to borrow money from friends to survive.

Family and biographers have suggested that Irving was the model for Stoker’s title character, Count Dracula: a charismatic man with an aristocratic appearance who could charm and cajole people into meeting his needs and give nothing in return.

The financial stresses created by Irving’s miserliness are to our benefit, however, since one of Stoker’s motivations in writing Dracula was to raise revenue. Not only was he supporting his wife and a child, but he was also assisting in paying off his father’s debts.

Being knowledgeable of the theater, Stoker would have known that the most lucrative and long-running plays of that time were melodramas which included some form of vampire. Victorian fascination with the occult was in full swing and Stoker himself retained his childhood interest in horrific and supernatural folk tales. The stage was set for the creation of Dracula.

But more than a brooding imagination and the need for cash fueled Stoker’s writing. In 1872, Dublin author Joseph Sheridan Le Fanu wrote Carmilla, a multi-layered, openly erotic story of the fair-haired Laura and her beautiful dark tormentor, Carmilla. La Fanu was faithful to the Eastern European vampire tradition and his story so intrigued Stoker that he, too, began researching vampiric folklore.

In 1890, he met Hungarian linguist Arminius Vambrey, who may have helped give Dracula the form that is now so familiar to all of us. Vambrey and Stoker dined and Vambrey discussed Vlad, known as The Impaler, the brutal Wallachian ruler of the 15th century, who fought for the Christian church, battling against the infidels who were invading Europe.

With Victorian industriousness, Stoker set about finding other sources of information and took copious notes as he crafted his novel. He spent his vacation in the library at Whitby, Yorkshire (he made the seaside community the site of the Count’s arrival to Great Britain) and did his homework on the Count’s European home so thoroughly that Stoker was praised for his accurate description of the Borgo Pass and Transylvania, an area that Stoker did not visit.

Much Freudian literary critique has been applied to Dracula, its artistic merit debated, and vehement arguments made that Stoker was a writer who was unconscious of much of of what his story symbolized. It is hard to believe that book seven years in the crafting and written by a man who intimately knew what made for good drama and audience appeal could have been unaware of what he was writing.

That Stoker was a complex man there is no doubt. While his fictional character in Dracula, Mina Harker, seemed to criticize the “New Woman” at every opportunity, at Trinity, Stoker vigorously defended feminist causes and professionally protected the business interests of actress Ellen Terry. He also wrote and spoke on behalf of censorship, stating that, “A close analysis will show that the only emotions which in the long run [cause] harm are those arising from the sex impulse.” Yet, he authored the era’s most sexually charged novel. But maybe the strongest duality in Stoker was how this leading man in London’s social scene, and era dominated by the belief that there is a rational explanation to all things, kept true to the Irish folk tradition that there is far more to life and the spirit than any mortal will ever come to know.

Bram Stoker’s Dracula: The Movie

Screenwriter James V. Hart spent 13 years trying to get the project he calls the “real” Dracula to the screen. “Bram Stoker’s book is a great literary achievement,” says Hart, “and I think Hollywood has truly diluted the story over the years. People don’t realize what a beautifully written piece of work it is.” Hart first became interested in 1977, when he read Bram Stoker’s novel. “And I couldn’t believe what a dramatic, powerful, erotic story was on the page, and that this narrative that I was reading with its wonderful high adventure climax had not ever been done on screen.”

Hart’s script was about to become a cable television movie when Winona Ryder stepped in. Winona had just signed with new agents who sent her a pile of scripts to read. The only one she really liked was James Hart’s version of Dracula. Meeting with Francis Coppola on another project, she took the script along. “I never thought he would read it,” Winona remembers. “I thought he would be too busy, or not interested, but he was the ideal choice. On my way out the door, I handed it to him.”

As it happened, Coppola had been a Dracula fan since he had read Bram Stoker’s novel aloud to a group of eight- and nine-year-olds as the teenage drama counsellor at a summer camp in upstate New York.

Says Ryder, “I think Francis and I liked the same things about the script, which was very romatic and sensual and epic, a real love story. It’s not really a vampire movie. To me, it’s more about the man Dracula, the warrior, the prince. He is unlike any other man – he’s mysterious and very sexual – attractive in an dangerous way.”

The character of Mina appealed to Ryder in a very contemporary way. Bram Stoker described Mina as having a man’s brain and a woman’s heart. “She’s very independent for her times,” says Ryder. “She has strength and intelligence, but her connection with Dracula is uncontrollable. Francis and I agreed on all of it.”

Coppola was a godsend to Hart, but the question remained: why another Dracula? Coppola’s answer is simple – no one ever did the book. Most of the previous incarnations of the story played havoc with Stoker’s novel – changing character’s names and identities, switching story elements, or eliminating them altogether. ♦

See documentary on Bram Stoker here.

This article was originally published in the November 1992 issue of Irish America.

Editor’s Note : The Bram Stoker Festival, in the atmospheric setting of the Upper Courtyard of Dublin Castle, where Stoker himself once worked, take place in Dublin each year.

To learn more about the festival visit Bram Stoker Festival.

Gee. can’t read any more of this – Needs editing, and not by ghouls. Bow for How, and then I found another glaring error. Glad you don’t do that with my work.

Gee, Carstens, I must have been having a bad time when I commented on your truly excellent article two years ago. You teach me a lot I did not know, thank you – almost inspires me to watch the movie. I’ll go look at a trailer.

All the best. Super article. Edgar Allan Poe’s father was an Irish actor, also.

Most interesting about Henry Irving being the model for the monster.

Ha!

We have modern vampires – Pelosi & Schiff & the Do Nothings!

Cheers

Hi Patrick,

We all have those days and thanks for the kind words. Your info about Edgar Allan Poe’s father is now sending my brain down an interesting path. Who knows where that will go!

All the best,

Carstens

WB Yeats candidly admits to being entranced by Henry Irving’s acting ability and ‘charm’ in his autobiography. Excellent article on Stoker.