With ingenuity, a lot of talent, and a passion for cooking, Barbara Lynch rose from cooking for the priests in her Southie neighborhood to one of the top chefs and restaurateurs in the country.

“Seven minutes and a world away” is how Boston chef Barbara Lynch describes the two places she has straddled in her life: one fancy, expensive and tasteful, the other unadorned, modest and down-home.

The first is the culinary world, where Lynch is an award-winning chef whose restaurants have shaped Boston’s hospitality landscape and strengthened the city’s reputation as a culinary destination. Her company, Barbara Lynch Gruppo, is a multi-million-dollar enterprise of seven restaurants, including No. 9 Park, her first restaurant, opened in 1998 across from the Massachusetts State House, and her newest, Menton, opened in 2010 on Congress Street. Together they represent Lynch’s culinary philosophy of elegant simplicity and style, plus meticulous service. Dining in one of Lynch’s restaurants is both a tasty and tasteful experience.

The second world is South Boston, the neighborhood just seven minutes from downtown Boston, where Lynch grew up, one of seven kids raised by a single mother. The Lynches lived in the Mary Ellen McCormack Housing Project built for World War II veterans who survived the war and came home to start anew. Often described by the media in mythical proportions, South Boston is a peninsula jutting into Boston Harbor, the place where Irish famine refugees straggled to in the 19th century, clinging together while facing down opposition from Boston’s Brahmin class. As a result, Southie residents share an unbridled, irrepressible loyalty for each other and for the neighborhood. Even as it became gentrified in recent years, to those who grew up here, South Boston will always be a well-spring of family and community values like loyalty, pride, and friendship.

In some respects, Lynch’s place in the glamorous culinary spotlight belies her true personality and temperament. The culinary world – and South Boston for that matter – is full of characters, many of them gregarious, audacious, larger-then life personalities who insist you pay attention to them. Lynch seems the opposite: she is low-key and alert until she has weighed up the situation, but then her wit, charm and intensity come quickly to the fore.

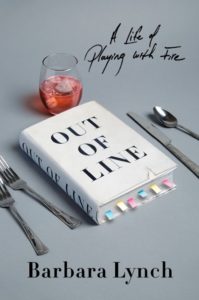

Both of Barbara’s worlds came into full focus this April, when her unvarnished, candid, and compelling memoir, Out of Line: A Life of Playing with Fire, was published by Simon & Schuster. Just a few days later, Time magazine named Lynch as one of its 100 most influential people in the world for her culinary and entrepreneurial skills. Joining Lynch on the list were Pope Francis, singers Ed Sheeran and Alicia Keys, and athletes Tom Brady, LeBron James, and Conor McGregor.

In the Times profile, Padma Lakshmi, host of the popular television show Top Chef, describes Lynch as someone who “gets things done; even when they seem impossible.” She calls Lynch “a great teacher and a true provider – not just of glorious foods but of different spaces for people to flourish and grow.”

There is some irony to the old sexist dictum that “a women’s place is in the kitchen,” given that the professional kitchens of luxurious hotels and fine restaurants have long been male bastions. Lynch helped changed that, and her ascension as one of America’s top chefs, male or female, was hard-won. In her book, Lynch credits trailblazers she learned from in Boston, including Julia Child and Lydia Shire.

“It’s been great fun and an honor to get to know Chef Lynch this past decade – a time when she has won numerous James Beard ‘Best Chef’ and other honors,” says Susan Ungaro, president of the James Beard Foundation. “I was especially delighted to see Barbara become the first female chef to win the ‘Outstanding Restaurateur of the Year’ in over 25 years – an extraordinary achievement in a category that historically was all men.”

A prevailing challenge for Lynch has been her life-long struggle to move beyond her modest upbringing while pursuing her passion for cooking. “My whole life I’d had to fight – to teach myself, to achieve, to prove what I could do, to overcome a million doubts and fears, including my own,” Lynch recounts.

She describes one occasion in Italy when she had just cooked an extravagant dinner for a friend’s wedding attended by influential food people. “I still felt tongue tied. I had periodic flare ups of awareness that my Southie accent, constant f-bombing and cultural ignorance marked me as a project rat. I wasn’t ashamed of who I was, but I didn’t want to be a curiosity.”

Growing up in Southie

The fact is, Lynch has always been proud of being from South Boston, and her memoir is a shout-out to this neighborhood of cops and firemen, politicians and judges, gangsters and athletes and dockworkers and iron workers. Lynch is a natural born storyteller, recounting tales of her family and her raggle-taggle girlfriends from the projects, who joined her in a childhood of fun, adventure and hijinks. Lynch and her childhood pals remain close friends to this day.

“We still hang out with each other,” she says, smiling at a recent memory. “We all turned 50 the last couple of years and they all came to my house, like 28 of them. There is plenty of space, but they’re all crowded together, practically sitting on each other. I said, ‘Guys, we don’t have to sit in one lounge chair, we can move around a little,’ and they’re like, ‘No, we like it like this.’

“From my perspective, and I think, my generation, the projects in general were paradise,” Lynch says in an interview. “Most families had seven kids, some as many as 13, many of them single-parent households, and it was usually a mom. We all looked out for each other. My mom lived by the police radio.”

Her mother, Barbara Kelleher, had married Phillip “Yapper” Lynch, a hard-drinking taxi-driver “with the gift of blarney his nickname implied,” Barbara writes. He died of alcoholism at age 34, right before Barbara was born, leaving his wife to raise the kids. It became a difficult life for her mom, Lynch writes, “Money was a constant worry. Between her paying jobs, the housework, and keeping a half-assed eye on us kids, my mother always teetered on the edge of burnout.”

Lynch describes the Southie mentality through her mother’s perspective. “My mother made sure we stayed grounded no matter what. ‘Tomorrow’s another day,’ she’d say, you could be famous, but it’s only for 15 minutes. Tomorrow’s a new day, so back at it. You could lose everything, and we had nothing to lose, so go for it.”

As a latchkey kid growing up in the projects, Lynch had numerous escapades. When she was 13, she and her friends commandeered an idling transit bus on West Broadway and drove it for a few blocks; Lynch steered while the others pushed on the gas and brake pedals. She shoplifted in the downtown department stores for beer money, and got into fist fights with other girls at high school. It was a hard life that can break a person, and that is why Barbara’s life has been inspiring to those who know her best.

“Growing up in the housing projects of South Boston, it took great courage for Barbara to look past all the obstacles and pursue a different path,” says her first cousin and Southie native, U.S. congressman Stephen F. Lynch. “She is the product of a neighborhood that puts a premium on loyalty and a strong work ethic. She was and is fearless.”

“For anyone to reach the top in such a competitive profession is a rare accomplishment,” says Boston’s mayor Marty Walsh, who grew up a few miles from Lynch in Dorchester. “But to do it after overcoming some of the barriers she faced as a working-class woman, it’s really special. I do think that the grit and the persistence that she learned growing up in South Boston had something to do with that.”

When the James Beard Foundation nominated Lynch for “Best Chef: Northeast” in 2003, Lynch wanted to celebrate. Instead of heading to town, she went to the Quiet Man Pub on West Broadway in South Boston, co-owned by her brother Paul, where the local patrons good-naturedly ribbed her – “Beard? I don’t know him. Did he live in Old Harbor? Who the hell is Jimmy Beard?”

Learning to Cook

“I wanted to be a nun at one point,” Lynch recalled when we spoke recently on the phone. “For some reason I felt like I needed a purpose in life.” At age 12, she was cooking and house-cleaning for the parish priests at nearby St. Monica’s Rectory and as a teenager worked at the Soda Shack in Southie, where she made steak and cheese subs. She was a cocktail waitress at the Bay Side Club in Southie, where State Senate President Bill Bulger held his legendary St. Patrick’s Day Breakfast gatherings and where the locals partied hard on the weekends. She got a stint with her mother at the St. Botolph’s Club on Commonwealth Avenue, a private gentlemen’s club founded in 1880 that only opened its doors to women in 1988. It was here she began thinking of becoming a chef. “I had dyslexia and A.D.D., so I figured if I could cook I would always have a job,” says Lynch. “I couldn’t follow anyone else’s formula; I couldn’t work in an office; so cooking was good for me.”

Lynch credits her home economics teacher Susan Logozzo with keeping her in Madison Park High School during the tumultuous school busing years by allowing her to take the home economics class multiple years in a row. Lynch calls Logozzo “not only a great teacher but a great role model.”

Lynch never turned down a cooking gig, even when it was beyond her skill set. “Half the excitement was the risk, the breath-taking, heart-stopping challenge,” she writes. “I’ll figure it out, I thought. I always have.”

One summer, Lynch finagled a job as assistant chef on the Aegean Princess, a dinner-dance cruise ship sailing between Martha’s Vineyard and Nantucket. The head chef promised to train her how to cook for 150 high-paying guests on a fancy ship, but he quit just days before the first cruise.

Undaunted, Lynch told the ship owner she could handle the job as head chef, and with no experience in banquet cooking, she somehow managed to cook enough steaks and lobsters, baked potatoes and corn cobs for the guests as “pure adrenaline was pumping through my veins.”

Lynch continued to take risks while building her company steadily between 1998 and 2012. After culinary pilgrimages to Italy and France, she created her own distinct French-Italian menu that won praise from Food & Wine magazine and the New York Times. She created a test kitchen/restaurant named Stir, which featured regular cooking classes and a massive cook book library. Her cookbook, Stir: Mixing it up in the Italian Tradition, won the Gourmand Award for Best Chef Cookbook in 2009. She opened a butcher shop, a grocery store, and a restaurant dedicated to fresh oysters. One of her restaurants, Sportello, is modeled after a 1950s-style soda fountain diner called Brigham’s that her mother took them to as children. Another place, called Drink, is dedicated to the art of the cocktail.

Looking back on that decade, her congressman cousin Stephen said, “I worried during the economic crisis of 2008. All the financial experts suggested that businesses slow down and ride out the recession. Instead, Barbara opened up three more restaurants and a grocery store and published a cook book, all hugely successful. Unbelievable. That’s impressive.”

Sustainable Future

Lynch’s relentless quest of taking chances and working non-stop eventually took a toll. Married with a young daughter, Marchesa, Lynch became introspective, questioning her self and her lifestyle. Approaching the age of 50, she decided it was time to confront her demons, including excessive drinking, an occupational hazard in the hospitality industry. She writes in her book that she “hunkered down, got to work on myself. I went to therapy. I ate healthy food. I boxed for exercise. I painted constantly. I stopped drinking.”

The change in lifestyle brought Lynch to a new chapter in her life that continues to unfold. In 2012, she was selected to join the prestigious Relais & Châteaux, an association of 550 of the world’s best chefs and their properties. She wrote in her bio that because she “wanted the opportunity to make others happy I became a chef. That feeling has never left me.”

That same year, wanting to give back to the community that nurtured her, she established the Barbara Lynch Foundation, dedicated to nutritional and culinary education for the people of Boston, especially children.

“I hold Barbara up to our young people, as an example of what you can do if you pick yourself up, learn from your struggles, and commit to your passions and dreams,” Mayor Walsh says.

“The fact that she’s kept her successful restaurant businesses close to home is an example of how she continues to help mentor, inspire and employ people in the Boston area who need work and a role model like her,” says Ungaro.

Lynch continues to discover new passions and dreams. She recently bought a five-acre property outside of the fishing town Gloucester, about 40 miles north of Boston.

“We have microclimates up here, so I want to make my own salt, and do some things with seaweed. I want to experiment with moss, and curing fish,” she says. Lynch is also working with the Gloucester Fishermen’s Wives Association and helping to establish a community garden so people can have fresh produce.

But her latest venture, Salt Water, Inc., brings Lynch right back to her home turf and also full circle to an earlier episode in her career involving cruise ships. She is partnering with Boston Harbor Cruises, the National Park Service, and Massachusetts Department of Conservation & Recreation to provide new menus for concession stands on Georges Island and Spectacle Island, and at the Boston Harbor Islands Welcome Center on the Rose Kennedy Greenway. Salt Water will also handle the food onboard the cruise ships transporting visitors from the mainland to the islands, and cater private events too.

Lynch says the new initiative can “redefine the way we celebrate through food with friends, family, and colleagues on Boston Harbor. I can’t think of a better way to highlight our mutual commitment to the community, Boston Harbor, and the city we love.”

On Irish Cooking

Like many Bostonians, Barbara Lynch was aware of her Irish American heritage long before she made her first trip to Ireland in 2014. In fact, one of her early forays into cooking was making Irish soda bread with caraway and currants.

So when Tourism Ireland and Boston Irish Tourism Association created a Gaelic Gourmet series in 2006 to bring guest chefs from Ireland to cook in Boston hotels and restaurants, Lynch was among the first Boston chefs to roll out the green carpet.

She immediately invited the visiting chefs and tourism officials to dine as her guest at No. 9 Park, making them feel welcome and trading cooking ideas with them.

Subsequently, Lynch has become “an amazing culinary ambassador who is passionate about Ireland and her Irish heritage,” says Ruth Moran, publicity and communications manager for Tourism Ireland. “She is keen to build awareness for the wonderful culinary renaissance that Ireland has experienced in recent years.”

During the Gaelic Gourmet Gala at Boston’s Hotel Commonwealth, where 10 Irish and American chefs cooked side-by-side, Lynch was paired with Darina Allen, the cookbook author and proprietor of Ballymaloe House and Cookery School in eastern County Cork.

“Darina had brought over her own butter and a full salmon with her from Ireland. She started talking to me about her cows and the grass they eat,” Lynch recalls, breaking into a Cork accent, “‘You’ll never have butter like this, there’s nothing like it in the world.’ I couldn’t wait to go over to Ireland and visit.”

Allen in turn recalls being hugely impressed by Barbara’s vitality and passion for quality ingredients. “She’s such an inspirational entrepreneur who uses beautiful ingredients creatively in her own very distinctive style,” she says.

The two chefs were reunited in 2014 when Lynch visited Allen’s Cookery School. “You have to go there and see her gardens,” she exclaims. “She has a microclimate there that’s just amazing: fig trees, kiwi trees. She made soda bread in planter pots that was just delicious. To me, that is what cooking is all about, nothing fancy, but it comes from the heart.”

On that note, Lynch is convinced that Irish cooking is unfairly overlooked in the culinary world, and she plans to do something about it.

“Everyone talks about Italian grandmothers or French mothers who teach their children how to cook, but nobody talks about Irish grandmothers. I feel that Irish cooking is underrated. I want to do an Irish cookbook of recipes from Irish grandmothers.” ♦

_______________

Michael Quinlin is author of Irish Boston (Globe Pequot, 2013) He co-founded the Boston Irish Tourism Association in 2000 and created Boston’s Irish Heritage Trail.

For more information, visit barbaralynch.com.

Leave a Reply